полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

In the historical development of our subject, which we are now following with greater or less strictness, we are only concerned with important developments and fresh types as they from time to time arise. We have therefore little to say for the present of the blue and white and of the wares with monochrome glazes of which we have so many superb specimens dating from the reign of Kang-he. We must, however, mention in passing the brilliant sang de bœuf vases especially associated with the early years of this emperor. As in the case of the ‘transmutation’ or flambé glazes, the deep red colour of this ware is produced by the action of a reducing flame upon a silicate of copper. It is known in China as Lang yao, and there has been some misconception as to the origin of the term. If, as the best authorities tell us, we are to derive the name from Lang Ting-tso, the famous viceroy of the Two Kiangs (the provinces of Kiangsi and Kiangnan) at the time of the accession of Kang-he, the earliest form of this Lang yao must be associated with a period (say about the years 1654-1668) which is otherwise quite sterile in the annals of Chinese porcelain.

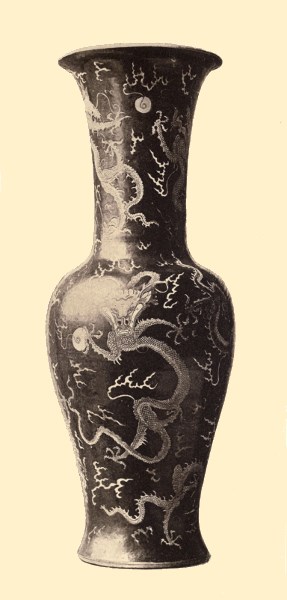

Plate XI.

Chinese. Black ground.

Yung-cheng (1722-1735).—When in 1722, after a reign of more than sixty years, Kang-he,61 perhaps the greatest of all the emperors of China, died, we find a note of alarm sounded by the Jesuit fathers. Unlike his father, Yung-cheng the new emperor was regarded as a supporter of the most conservative traditions, and no friend of the Christian missionaries. What, however, is important to us is the fact that as crown-prince he was known not only as a patron of the works at King-te-chen, but as himself an amateur potter of distinction. The Père D’Entrecolles, writing before Yung-cheng’s accession to the throne, tells us that it was his habit to send down from Pekin examples of ancient wares to be copied at the imperial factory. This influence, exercised in a conservative direction, is reflected in the porcelain produced during his reign.

This is indeed a critical point in the history of Chinese porcelain. We are reminded of some similar periods in the development of our Western arts, when it begins to become evident that a command of material and a technical finish have been attained at the expense of all spontaneity and freshness of expression. Some such tendency was accompanied at this time in China by a careful and deliberate imitation of ancient forms and glazes. Under Nien Hsi-yao, the new superintendent at King-te-chen, some advance was certainly made—we shall speak of the Nien yao and the new colours that distinguished it directly. We must not overlook, however, the influence of the foreign demand which more and more made itself felt, an influence opposed to the conservative and classical tastes of the emperor.

But when we run through the long list, under fifty-seven headings, of the various wares copied at King-te-chen at this time,62 we see how strong this classical influence was. In fact, this catalogue is one of our best sources of information for the ancient, and especially for the Sung, wares. The chief concern of the compiler was with the glazes, for no attempt seems to have been made to copy the thick and rough pastes of the early days.63 We can infer from some of the heads of the list that most of the highly perfected glazes of the day, ranging through every shade of colour, were considered to be but modifications of the old simple glazes of Sung times. This was an essentially Chinese way of looking at the matter, and by this indirect path it was possible to reach the most novel effects. Among the later headings of Nien’s list (it was to some extent chronologically arranged) we find mention of copies of Japanese wares, and frequent reference is made to colours and decorations of European origin. We shall have to make more than one reference to this important catalogue in a later chapter.

It was under the régime of Nien Hsi-yao that this list was drawn up. He was the second of the great viceroys whose names are associated with the emperors Kang-he, Yung-cheng, and Kien-lung respectively. He succeeded to Tsang Ying-hsuan, and was followed in the next reign by Tang-ying. The wares made during the administration of these superintendents are known in chronological order as Tsang yao, Nien yao, and Tang yao. This Nien did not regard his post by any means as a sinecure. He frequently visited the works, and required samples of the imperial ware to be sent every two months to his official residence for inspection (Bushell, p. 361).

The Nien yao, to the Chinese collector, is especially associated with certain monochrome glazes—above all with the clair de lune—the yueh pai or ‘moon-white,’ and with a brilliant red glaze with stippled surface, a near cousin to the sang de bœuf and flambé classes. There is another ‘self-glaze’ ware which dates from this time, of which the mingled tints depend, as in the case of the flambé, upon the varying degrees of oxidation of the copper in the glaze. This is the ‘peach-bloom,’ the ‘apple red and green’ of the Chinese. The charm of this delicate ware is of another kind to that to be found in the vigorous flashes of colour of the transmutation glazes.

We can trace at this time the gradual introduction of two new colours that give so special a character to the wares of the next reign. I mean the pink derived from gold and the lemon-yellow. These colours were used sparingly and with great delicacy at first, but we come to associate them at a later time with a period of decline and of bad taste.

Kien-lung (1735-1795).—It was during the long reign of this emperor, poet and patron of all the arts, that the new direction which we find given to the porcelain made in the reign of his father, Yung-cheng, became even more accentuated—on the one hand, the copying of old glazes and the employment of archaic hieratic patterns for decoration, on the other, the more and more frequent use of new colours and new designs of non-Chinese origin. This latter tendency was fostered both by the eclectic tastes of Kien-lung himself and also by the increasing importance of the demand for foreign countries. Great care was given to the paste—it was required to be of a snowy (or rather sometimes chalky) whiteness, tending neither towards yellow nor towards blue, and so carefully finished on the lathe that on the uniform glassy surface of the finer specimens no signs were left of the movement of the potter’s wheel;64 for compared with the ware produced in Ming times, and even during the reign of Kang-he, we now note the greater proportion of pieces thrown on the wheel. At no time has the skill of the potter who threw the clay, and of the workman who then pared and smoothed the surface on the lathe, been brought to a greater perfection, and this applies not only to the eggshell china, but to the large vases and beakers, so perfect in their outline. The same perfection of technique is found in the decoration, so that a blue and white vase of this period can at once be recognised in spite of the pseudo-archaic decoration and the Ming nien hao inscribed on the base. When the new colours are introduced the date is, of course, approximately fixed, and we may probably associate with the beginning of this reign (or perhaps a little earlier; see note on p. 110) the first use of the rouge d’or which has given its name to a well-known class of porcelain—the famille rose.

A manageable red had long been a desideratum. There was no more treacherous material than the basic copper oxide, whether painted under or mixed with the glaze. As an over-glaze source of red this pigment was of course unavailable, while the opaque brick-like tints obtained from iron, though in keeping with the rougher, picturesque decoration of early times, did not harmonise well with the delicate style of painting now in fashion,65 so that it is not surprising that the beautiful pink tint obtained from gold carried all before it. The gold was probably incorporated with the enamel flux in the form of purple of Cassius, which is readily prepared by dissolving gold in a mixture of nitric acid and sal-ammoniac and adding some fragments of tin. The colour had been known for some time in Europe—we can perhaps even trace this pink tint on enamelled Arab glass of the fourteenth century (see page 89).66 A very small quantity of this material goes a long way, especially when used to give a gradated tint to a white opaque enamel, as on the petal of a flower. As a colour it is singularly harmonious, and in a period of decline helped to ‘keep together’ the motley array of enamels used along with it.

There is nothing more popular in the work of this time than the little egg-shell plates, decorated with flowers and birds, for which such high prices are given by collectors. The original type, for both ware and decoration, is probably in this case to be found in the ‘chicken-cups’ of Cheng-hua’s reign.

On the plates of this ware the borders are filled with elaborate and minutely finished diapers and scrolls, evidently taken from silk brocades; indeed, the gold threads of the woof are sometimes directly imitated; the centre is occupied by a picture, either a flower piece or a genre figure scene (Pl. xii.). We may connect these designs with the works of the naturalistic colour school of the time, many of the finest of which have been preserved by Japanese collectors. A very frequent subject is a rocky bank from which grow peonies, narcissi, or other flowers, and under which two or more chickens or sometimes quails are grouped. The petals of the flowers are rendered by a white opaque enamel in high relief, often with a flush of pink, imitating the tour de force by which the painters of the time, by a single stroke of the brush, produced a full gradation of colour. Indeed, the same artists doubtless painted both on silk, on paper, and on porcelain. We may compare their work to that of the fan-painters and miniaturists who were employed to decorate the panels of Sèvres porcelain, at this very time, with pastoral scenes and flower pieces. The Chinese enamellers rarely signed their work; but there is a plate in the British Museum with the name of a Canton artist. This gives a hint as to where most of the work was done. But the most remarkable instance of signed work of this period is found on a series of large plates in the Dresden Museum. On these a Chinese artist, some time before the middle of the eighteenth century, has painted a series of designs of birds and flowers, and in one instance at least a graceful female figure. On the field, in each case, we find a seal character (accompanied either by a smaller mark contained in a circle, or by an artemisia leaf) which indicates the painter’s name. With true artistic feeling he has succeeded in filling the surface of the plate with a graceful decoration, and at the same time he gives us a series of delightful pictures, employing the full range of the enamel colours at his command. And in thus combining a decorative design with an accurate rendering of natural objects, the Chinese artist has succeeded in doing what has never been accomplished by any European painter on porcelain.

PLATE XII CHINESE

In decoration of this kind, however, only the very best work pleases; in anything below this we get at once to what is vulgar and trite; and the larger palette now at the painter’s command only makes it easier for him to produce the unpleasant combinations of colours so frequent in the wares exported from China after the end of the eighteenth century. On the other hand, the older painters, confined to their three or at most five colours, seldom fail to produce an agreeable effect, however roughly their colours are daubed on.

In the genre scenes, as in the case of the flower pieces, a realistic tendency is prominent. We have no longer the Taoist saints or the hunting and battle pieces of earlier times, but delicately executed interiors with graceful figures of girls arranging flowers or painting fans, or again, landscapes with men travelling by road or by river. There is a refinement of colour and a charm of drawing and composition in the better specimens of this somewhat effeminate school that appeals to every one. It is difficult for us to find any marked European influence in the designs of this time, and yet these pictures are classed by the Chinese as European in style; and it is not quite clear whether this refers only to the enamel colours employed or to the manner of drawing as well. Most of the work of this kind was doubtless made for the European market and painted at Canton. But is this the case with the finest examples? Kien-lung himself was, it would seem, no despiser of this carefully decorated ware. A poem of his composition, signed with the vermilion seal, is often found on this egg-shell porcelain.

On some of the most highly finished of the little cups and plates we find an elaborate scroll decoration in gold and sometimes in silver; and in these designs we may perhaps trace the influence of the baroque style in vogue at this time in Europe.

Nien resigned his post when his master in the year 1735 had ‘flown up to heaven like a dragon,’ and the new emperor, Kien-lung, appointed in his place Tang-ying, who had long served under him. The new director was no less an enthusiast than his predecessor. He tells us in his memoirs—for he was a man of literary taste like his master, Kien-lung—that he served his apprenticeship with the workmen, sharing his meals and his sleeping-room with them, following in this the proverb which says ‘the farmer may learn something from his bondman, and the weaver from the handmaid who holds the thread for her mistress.’

We hear that new tints of turquoise (fei-tsui) and of rose-red (mei-kwei) were introduced by him, and we may perhaps identify these colours with certain shades of pink and turquoise blue that became prevalent about this time. In both these cases the pigment is mixed with some amount of arsenic or tin so that the enamel is nearly opaque, and this enamel is now spread over the ground, taking the place of the glaze which lies beneath. The effect, though apparently admired by some collectors, is heavy and unpleasant. The pink, which we may consider as a Chinese equivalent of the rose Pompadour (it is uncertain whether the French or the Chinese were the first to use the rouge d’or colours), is generally more or less opaque, with a granular surface; it is often found covering a paste inscribed with fine scrolls.67

PLATE XIII. CHINESE

In the case of the pale opaque blue (to which the name of turquoise may be applied more aptly than to the sky-coloured transparent blues of the demi grand feu), the surface of the enamel is sometimes painted with an irregular net-work of black lines, as if in imitation of some kind of marble. This turquoise enamel towards the end of Kien-lung’s reign was often applied to the surface of large vases, and when in combination with a lemon-yellow decoration the effect is even more unpleasant than when used alone.

We have mentioned, when speaking of Yung-cheng’s reign, a valuable list of the various kinds of porcelain made at that time at King-te-chen. We must now refer to another document, quoted, like the list of Nien’s time, in all the Chinese books dealing with the history of the imperial porcelain works. The emperor Kien-lung, it would appear, when overhauling certain manuscripts preserved in the palace, came upon a series of twenty water-colour drawings illustrating the manufacture of porcelain. He at once summoned Tang-ying, the famous superintendent at King-te-chen, to Pekin, and, handing over the drawings, commanded him to prepare a full description of all the processes illustrated in these pictures. This was in 1743, shortly before Tang’s retirement. The drawings themselves have never been made public; but we have in Tang’s report what is, after the letters of the Jesuit father, our most important source for the technical details of the manufacture of porcelain in China. With these details we are not concerned just now, but we will quote from Dr. Bushell’s translation a disquisition on certain principles that should govern the forms and decoration of porcelain. This is a kind of obiter dictum of Tang-ying, à propos of the fashioning and painting of vases. In his flowery style he tells us (I abbreviate in a few places): ‘In the decoration of porcelain correct canons of art should be followed. The designs should be taken from the patterns of old brocades and embroidery; the colours from a garden as seen in spring-time from a pavilion. There is an abundance of specimens of ware of the Sung dynasty at hand to be copied; the elements of nature supply an inexhaustible fund of materials for new combinations of supernatural beauty. Natural objects are modelled to be fashioned in moulds and painted in appropriate colours. The materials of the potter’s art are derived from forests and streams, and ornamental themes are supplied by the same natural sources.‘68 It is a strange fancy which connects the decoration of a vase with the source of the materials with which it is made. Elsewhere, speaking of the painting of the blue and white ware, Tang-ying says: ‘For painting of flowers and of birds, fishes and water-plants, and living objects generally, the study of nature is the first requisite. In the imitation of Ming porcelain and of ancient pieces, the sight of many specimens brings skill.’ We see in this a kind of hesitation, a balancing between two influences—the naturalistic and the traditional—which is characteristic of the period.

We may call attention, by the way, to the important place that is given in this report to the process of moulding in the fashioning of a vase, especially as supplementary to the throwing on the wheel, and above all, to the care required in the turning and polishing on the jigger or lathe to ensure accuracy of outline in the finished piece.

The last picture described by Tang-ying illustrates the worshipping of the local god and the offering of sacrifice. And we are told the story of how, when the great dragon-bowls failed time after time, and when, in consequence, the workmen were harassed by the eunuchs sent down by the Ming emperor, Tung the potter leaped into the furnace; and how, after this sacrifice, when the kilns were opened, the bowls were at last found perfect in shape and brilliant in colour. So Tung was worshipped as the potter’s god; and, indeed, Tang-ying tells us, as a voucher for the truth of his story, that in his time one of these very dragon fish-bowls, ‘compounded of the blood and bones of the deity,’ still stood in the courtyard of the temple, a witness to the sacrifice (Bushell, chapter xv).

Tang-ying resigned his post in 1746; his influence was therefore only felt during the first years of Kien-lung’s long reign. His is the last name that can be personally connected with any Chinese ware, unless it be that of the emperor his master.

Kien-lung was a poet, and a very productive one—his complete works were published in an edition of 360 volumes, containing nearly 34,000 separate compositions. These are generally occasional pieces suggested by the aspects of nature. Such verses are not unfrequently found on the egg-shell porcelain of his time, signed, too, with the vermilion pencil. There is quite a long poem of his on a dish of thin ware now in the Musée Guimet in Paris.

The emperor interested himself in a new kind of opaque glass made in Pekin by a skilful artist, one Hu, and he sent specimens of this ware to King-te-chen to be imitated in the nobler material, as he deemed it. This was effected by means of a very vitreous paste, and the little snuff-bottles moulded in high relief in this material are much prized both by Chinese and American collectors.

There was, indeed, at this time a rage for imitating other substances in porcelain, which was doubtless fostered by the increased command of technical processes and of new colours. A good deal of the porcelain covered with black or sometimes brown lacquer,69 inlaid with mother-of-pearl, the laque burgauté of the French, dates perhaps from an earlier period. But the little snuff-bottles, imitating jade, pudding-stone, agate, turquoise, as well as silver, gold, and bronze of varied patinas, or again the rusted surface of iron—to say nothing of wood, bamboo, and mother-of-pearl—may, with few exceptions, be attributed to this time. We may compare such work to the contemporary triumphs of the Japanese in lacquer.70

But by the middle of the century it is no longer the demand of the court that gives the general tone to the productions of King-te-chen. The taste for Oriental wares had spread among the middle classes in Europe. The English were taking the place of the Dutch as the principal exporters, and this change was reflected in a demand for a gaudy ware crowded with a motley array of figures, the ‘mandarin china’ properly so called. As to the extensive class of porcelain painted with coats-of-arms and other European designs, a class well represented in the British Museum, we will only mention that the greater part was decorated at this time by a special school of artists at Canton, though some pieces date from a somewhat earlier period.

Kia-king (1795-1820), the son and successor of Kien-lung, was like his father a poet, but a man of weak and dissolute character. The high finish of the previous reign was, however, maintained, and the pieces marked with this emperor’s name are sought after by Chinese collectors.

Tao-kwang (1820-1850).—It is surprising that so much really good porcelain was made at a time so troubled by foreign wars and internal rebellion. In some of the blue and white ware of this and even the next reign, we may sometimes see a return to the breadth and boldness of treatment characteristic of earlier days. In the coral-red grounds of this time, the intractable iron oxide appears to have been more thoroughly incorporated with the glaze than at any previous period. It is to this reign that we may assign the ‘Pekin’ or ‘Graviata’ bowls, with reserved panels on the outside filled with flowers, landscapes, etc., in many coloured enamels. The ground is often of a pinkish rouge d’or, or in other instances of lemon yellow, blue or pale lavender. The inside of the bowl has a decoration of blue and white.

Hsien-feng (1850-61).—As at the beginning of this emperors reign the Taiping rebels broke into Kiang-si and burned down the town of King-te-chen, this period is of necessity a blank in the history of porcelain.

Tung-chi (1861-1874).—In the third year of this reign the rebels were driven out from King-te-chen and the imperial works rebuilt. A large order was at once sent from Pekin for porcelain of every description. The details of this order, the latest of the lists of this kind to be found in the Annals of Kiang-si, are only given in the edition of that work published since the date of Julien’s translation. This list is translated by Dr. Bushell, fifty-five headings in all, and we find in it a curious instance of the survival of the old traditions. All the wares mentioned in the older lists are now again requisitioned for the use of the court.

The Empress-Dowager, who has held the reins during the minority both of Tung-chi and of his successor, the present emperor, is reputed to be something of a connoisseur,71 and to take an interest in the imperial manufactory. Some of the better class wares from the palace and from the temples at Pekin have quite lately found their way to England, and specimens may be seen on loan at South Kensington. I notice especially a set of five vessels in deep blue from the Temple of Heaven. The execution appears to be careful, but the forms are ugly and the blue of an unpleasant tint. In vessels of this kind, however, both shape and colour may be governed by tradition. Mr. Hippisley, who has lived long in China, says that for some years past the famille verte wares of Kang-he’s time, especially the vases with black ground and prunus flowers, have been fairly well reproduced at King-te-chen, as have, later still, the so-called ‘hawthorn ginger-jars.’ But in China, as in France, it is with the difficulties of the copper glazes, the flambé and the sang de bœuf, that the majority of our contemporary ceramic artists are striving.