полная версия

полная версияPorcelain

We have now, however, one source of information for these early wares upon which, although it is in a measure a literary source, we can place greater reliance. This is nothing less than an illustrated list, a catalogue raisonné, of famous specimens of porcelain, drawn up by a distinguished Chinese art connoisseur and collector as long ago as the end of the sixteenth century. In this manuscript there were more than eighty coloured reproductions of pieces, both from the author’s own collection and from those of his friends. The work came from the library of a Chinese prince of high rank, and it was purchased in Pekin by Dr. Bushell some twenty years ago. Since then this valuable document has perished in a fire at a London warehouse, where it had been deposited, but not before the illustrations had been copied by a Chinese artist and its owner had made a careful translation and analysis of its contents.29 The writer, Hsiang-yuan-pien, better known as Tzu-ching, after giving a brief sketch of the early history of ceramics in his country, exclaims apologetically: ‘I have acquired a morbid taste for pot-sherds. I delight in buying choice specimens of Sung, Yuan, and Ming ware, and exhibiting them in equal rank with the bells, urns, and sacrificial wine-vessels of bronze dating from the three ancient dynasties, from the Chin and the Han’ (2250 B.C. to 220 A.D.)—that is to say, in placing them in the same rank as antiquities that are acknowledged to be worthy of the attention of the scholar. Porcelain at that time, we see, had hardly established its claim to so dignified a position; hence the apologetic tone. After telling us how with the advice of a few intimate friends he had selected choice specimens, which he then copied in colour and carefully described, Tzu-ching concludes with these words: ‘Say not that my hair is scant and sparse, and yet I make what is only fit for a child’s toy.’ This appeal is evidently addressed to the Lord Macaulays of his day.30

The first point to notice in this catalogue is that more than half of the objects described are attributed to the Sung period (960-1279 A.D.), that is to say, they were at least three hundred years old at the time when Tzu-ching wrote. The Sung dynasty, we must bear in mind, was above all remembered as a period of great wealth and material prosperity. Less warlike than the Tang which preceded it, the arts were cultivated at the court of the pleasure-loving emperors who had their capital during the earlier time at Kai-feng Fu (in the north of Honan, near to the great bend of the Hoang-ho). When driven south by the advance of the more warlike Mongols they retired to Hangchow, the Kinsay of which Marco Polo has such wonderful tales to relate. In these early days there was no great centre for the manufacture of porcelain; it was made in many widely separated districts, so that the classification of these early wares is, in a measure, a geographical one. At King-te-chen, at least in the later Sung period, they were already making porcelain, but for court use only, it would appear, for at that time the factory was a strict imperial preserve, and its wares did not come into the market.

As to the still older wares, those of Ch’ai and of Ju, which generally hold the place of honour in Chinese lists, it was of the first that the emperor spoke when he commanded that pieces intended for his own use should be clear as the sky after rain; but no specimen of this porcelain was extant even in Ming times. Its place, it would seem, was taken by the Ju Yao (the word yao is about equivalent to our term ‘ware’), which, like the Ch’ai, came from the province of Honan. This ware also is now practically extinct; Tzu-ching, however, claims to have possessed some specimens, and of these he gives more than one illustration. The glaze was thick and like melted lard (a comparison often made by the Chinese), and varied in colour from a clair-de-lune to a brighter tint of blue. The name Ju, we may add, is often applied to more modern glazes which resemble the old ones in colour and thickness.

The name Kuan yao, which means ‘official’ or ‘imperial’ porcelain, has been the cause of much confusion; the term has been applied to any ware made for imperial use. That of the Sung dynasty was made in the immediate neighbourhood of the imperial court, first at Kai-feng Fu and later at Hangchow. In its more strict use the term Kuan yao is applied to pieces generally of archaic form, to censers ornamented with grotesque heads of monstrous animals, and to wares of other shapes copied from old ritual bronzes. The glaze varies in colour from emerald green to greyish green and clair-de-lune, it is generally crackled, the cracks forming large ‘crab-claw’ divisions. Other kinds are described as white and very thin, but of these, perhaps for one of the reasons given above, no examples have survived to our day.

Lung-chuan yao and Ko yao. It will be convenient to class together these two most important types of Chinese porcelain. At the present day these names are applied in China to some comparatively common varieties of porcelain, not necessarily of any great age. But more strictly Lung-chuan yao is the term used by the Chinese for the heavy celadon pieces, whether dating from Sung or from Ming times, which were the first kinds of porcelain to become a regular article of export; while the word Ko yao is used as a general name for many kinds of crackle ware, which may vary in colour from white to a full celadon. In a more restricted sense it includes only the early pieces with a greyish white glaze and well-marked crackles.

Lung-chuan ware was made during Sung times at a town of that name in the province of Chekiang, situated about halfway between the Poyang lake and the coast. In Ming times the kilns were removed to the adjacent provincial capital, Chu-chou Fu, nearer to the coast. This was probably the ware that Marco Polo saw when passing through the town of Tingui. It was largely exported from the ports of Zaitun and Kinsay. It will, however, be better to defer the discussion of this thorny question to a later chapter, when we shall have something to say about the way in which the knowledge of Chinese porcelain was spread through the Mohammedan and Christian west. It will be enough for the present to mention that the Lung-chuan ware was the original type and always remained one of the principal sources of the Martabani celadon so prized in early Saracen times.

As this is the first time that we come across celadon ware,31 we may mention that we use the term in the older and narrower sense for a greyish sea-green colour tending at times to blue. The name is, however, sometimes made to cover nearly the whole range of monochrome glazes. It is the Ching-tsu32 of the Chinese and the Sei-ji of the Japanese.

The true Lung-chuan celadon of Sung times was, however, of a more pronounced grass-green colour. But we are concerned rather with the later celadon made at Chu-chou Fu during the Ming period. For it is to this time that we must refer most of the heavy dishes and bowls, often fluted or moulded in low relief with a floral design of peony or lotus flowers, or again with plaited patterns surrounding a fish or dragon which occupies the centre; in other examples the decoration is engraved in the paste. In either case, whether moulded or engraved, the glaze accumulating in the hollows helps to accentuate the pattern. The paste as seen through the glaze where the latter is thin appears white, but where the glaze is absent, as on the foot, or where it is exposed by bubbles or other irregularities, the ground is seen to be of a peculiar reddish tint. By this test the Chinese claim to distinguish the older celadon, the true martabani, from the later imitations made at King-te-chen. The paste of these later copies is often artificially coloured on the exposed surface so that they may resemble the old ware (Hirth, Ancient Porcelain, pp. 21 seq.).

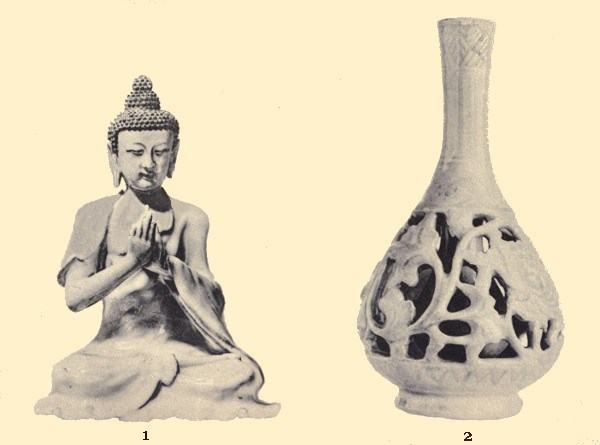

PLATE III.

1—CHINESE, CELADON WARE

2—CHINESE, CELADON WARE

As for the Ko yao, the old ware of Sung times is said to have been first made in the twelfth century. The Chinese character with which ‘Ko’ is written means ‘elder brother.’ According to the books there were at this time at Lung-chuan two brother potters named Chang. The elder brother leaving the younger Chang to continue in the old ways, started to make a new ware distinguished by the crackle of its glaze. This was originally a thick, heavy ware, with the iron-red foot and white paste already noticed, but, as we have said, the name is now used for a large class of crackle ware with a glaze of celadon, of greyish white and especially of a yellowish stone colour. This porcelain with grey and yellowish crackle does not seem to have been so largely exported as the uncrackled celadon; bowls and jars of a similar ware have, however, been found in Borneo and in the adjacent islands.

Chün yao.—It is to this ware that we may trace back the now famous family of flambé porcelain. Chün yao was already made in early Sung times, i.e. before the Mongol conquests of the twelfth century, in Honan, not far from the old capital of Kai-feng Fu. A description in a work of the seventeenth century leaves no doubt as to its identification. ‘As to this Chün yao,’ the writer says, ‘a fine specimen should be red as cinnabar, green as onion-leaves or the plumage of the kingfisher, and purple, brown, and black like the skin of the egg-plant.’ We have here the description of that ‘transmutation’ or flambé ware of which such magnificent examples were made at King-te-chen in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and which has lately been successfully imitated in France. The play of flashing colour in the glaze was said to have been originally the result of accident, but we must not attach much importance to statements of this kind. In the old Sung pieces the clay is less white and fine than in the highly finished examples made at King-te-chen during the reigns of Kang-he and Yung-cheng. On the Sung ware we may frequently find a number (from one to nine) engraved, sometimes more than once, in the paste, and these characters are carefully copied in the later reproductions. We have here perhaps the earliest instance of the employment of a mark on porcelain. The old writers tell us apologetically of the vulgar names given, by way of joke, it would seem, to these glazes, such as mule’s lungs or pig’s liver—no inapt comparisons, however, for some of the effects seen in these old wares. These varied hues were of course obtained from copper in the first place, though the presence of iron, in both stages of oxidation, may sometimes add to the variety of the tints.

Kien yao.—This was a dark-coloured ware made at Kien-chou, north-west of the port of Fuchou. It must not be confused with the well-known creamy-white ware of Fukien, exported in later days from the same port. Certain shallow conical cups of this ware, with a vitreous glaze, almost black, but relieved around the margin with small streaks and spots of a lighter colour, were especially valued from very early times for the preparation of powdered tea—nowhere more than in Japan, where an undoubted specimen of this Kien ware is treasured as a priceless heirloom. There is an excellent specimen in the British Museum: a careful examination of this little bowl will give no little aid in understanding what are some of the qualities that are looked for in China and Japan in these old glazes. There is a quiet charm in the glassy surface, and an air as of some quaint natural stone carefully carved and polished rather than of a product of the potter’s wheel.

Ting yao.—In the Ting yao of the Sung dynasty, as in the case of the contemporaneous celadon and crackle wares, we have the oldest type of an important class of porcelain. The earlier specimens have served more than once as models for famous potters of Ming and later times. It was probably at Ting-chou, a town in the province of Chihli, to the south-west of Pekin, that a brilliant white porcelain was first successfully made by the Chinese, possibly as early as the time of the Tang dynasty; and the name of Ting yao has remained associated with all pure white wares of a certain quality, even though made at other places. As in the case of the celadon porcelain, the decoration, if any, was either in low relief or incised in the paste; but in opposition to many of the other wares we have mentioned, the Ting porcelain seems from the first to have been made from a paste of great fineness, its translucency was at times considerable, and the patterns were engraved or moulded with much delicacy. The design when engraved is scarcely visible unless the vessel is held up to the light. The specimens of Ting ware that survive date probably from Mongol or from Ming times. The British Museum possesses a remarkable collection of these Ting bowls and plates. A pair of very thin pure white shallow bowls are noticeable as having in the centre an inscription finely engraved in minute characters under the glaze. It is the nien-hao or year-mark of the Emperor Yung-lo (1402-1424), the first great name among the emperors of the Ming dynasty. This is perhaps the earliest date-mark with any pretentions to genuineness that has been found on the Chinese porcelain in our collections. The decoration, in this case, is formed by a five-clawed dragon faintly engraved in the paste. These bowls are specimens of the feng or ‘flour’ Ting ware (also known as Pai or ‘white’ Ting), but most of the Ting plates in the same collection are of quite another kind of ware, which has a surface like that of a European soft-paste porcelain—this the Chinese know as the Tu-Ting or earthy Ting. This latter ware has in fact a soft lead glaze covering a hard body, and must therefore have required two firings, the first to thoroughly bake the paste, and a second at a lower temperature to melt the glaze on to it. Some of the specimens of this Tu-Ting in the British Museum are said to date from Sung times. I do not know what is the authority for the use of a lead glaze in China at so early a date. Many of these plates have certainly a great appearance of age, but this antique look is due in some measure to the ‘weathering’ of the soft glazes on the exposed surfaces. This weathering has brought into prominence the very graceful decoration of lotus-flowers, but the surface is often discoloured by stains as of some oily matter which has apparently found its way under the glaze. The copper bands with which the edges of many of these plates are bound are mentioned in the old accounts; those in use in the palace, it is said, were fitted thus with collars to preserve the tender material.

We must postpone the account of the rival white ware, the creamy porcelain of Fukien, or later Kien yao, as none of it was made as early as the time of the Sung dynasty. The Kien yao of that time, as we have seen, was quite another ware.

We have now mentioned the most important of the classes of Chinese porcelain that date from early times. We have confined our brief notice to the varieties of which specimens have survived, laying special stress upon those kinds which have, as it were, founded a family, and which we can therefore study in specimens from later ages. The names of many other wares of both the Sung and Tang periods may be found in Chinese books, but of these we do not propose to say a word.

The paste of these early wares is rarely of a pure white, and their translucency is generally very slight, but they are not for that reason to be classed as stonewares. The materials were probably in all cases derived from granitic rocks, that is to say, from a more or less decomposed granite (containing mica and often a certain amount of iron) mixed with some kind of impure kaolin. Professor Church, in his Cantor Lectures, gives us two analyses of ‘old Chinese ware,’ which confirm this view. One specimen, with a white body, was found to contain 75 per cent. of silica, about 18 per cent. of alumina, and about 5·5 per cent. of alkalis (chiefly potash). The other, of brownish coloured paste, contained a little less silica, but as much as 2·5 per cent. of iron. For the roughly prepared material of these old wares we would prefer the name of proto-porcelain or kaolinic stoneware, so that there may be no confusion with the true stoneware of Europe, a quite different material.33

In the absence of more ordinary clays in the central and northern parts of China, some such kaolinic pottery may have been made by the Chinese from very early times. When in Tang or in earlier days it occurred to them to attempt to imitate jade or other natural stones, they had the good fortune to be already using materials that allowed of these experiments being after a time crowned with success. The important point that still remains unsettled is at what date they first succeeded in covering a ware of this class with a vitreous coating. For the date of the first use of glaze in China we can at present only give a very wide limit, let us say some time between the first and the fifth century of our era. Very probably it was their acquaintance with the nature of glass that put them on the right track. This material, it is said, they first knew of from their intercourse with the later Roman empire. There is some reason to believe that they acquired at the same time the secret of its manufacture, though, according to the Chinese, the art was lost at a later time.34

We can now form some idea of how far the art of making porcelain had advanced at the time when the tide of the Mongol invasion swept over the country. Our knowledge of the wares made at this time must be derived chiefly from the imitations of the older porcelain made at a later period, but in such a conservative country as China this reservation is of no great importance. We must remember that in all these wares there was no other decoration than that given by the glaze as applied to the variously moulded or incised surface of the paste. The nature of the glaze was therefore of pre-eminent importance. The range of colour, except in the rare flambé vases, was in the main confined to shades of blue and green, and even of these colours pronounced tints are rare. All the colours at the command of the potters of these days were derived from the oxides of iron and copper. And yet with such simple elements, what an infinite variety! It has been truly said by a French writer that the beauty of the glaze is the qualité maîtresse de la céramique, and it is partly a recognition of this claim that has led so many French and American collectors, of late, to follow the example of the Chinese and Japanese connoisseurs, and to give so marked a preference to monochrome porcelains, which owe their charm to the merits of the glaze alone. But the specimens we find in these collections are with but few exceptions of much later date. The price that a fine piece of Sung ware, above all if it has a good pedigree and comes from a known collection, has always commanded in China has sufficed, at least until quite lately, to keep such specimens in their native country.

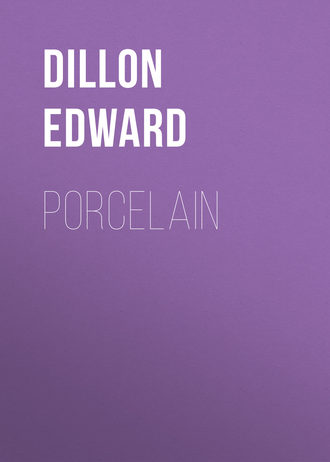

PLATE IV. CHINESE

As we have said, there are very few examples in our public collections that can with any assurance be attributed to Sung times. In the British Museum, in the same case with the Kien yao tea-bowl already mentioned, is a jar some twelve inches in height, with two small handles on the shoulder. It is of irregular shape and covered with a thick glaze of a pale turquoise blue, faintly crackled. Close to the mouth is a bright red mark, like a piece of sealing-wax, due probably to the local partial reduction of the copper. This beautiful but very archaic-looking jar (Pl. iv.) is attributed to no earlier date than the later or southern Sung dynasty (1127-1279). Among the large number of crackle monochrome pieces in the same collection there are many specimens which a Chinese connoisseur would classify as Ko yao, and similarly some of the old flambé pieces might be termed Chün yao, without definitely assigning them to Sung times. The Lung-Chuan celadons are represented by some early pieces, more than one distinguished by the red foot. There are some fine plates of old heavy celadon at South Kensington, not a few purchased in Persia. Here may also be found a celadon jar cut down at the neck; and the ‘mouth’ thus artificially formed has been carefully stained of a red colour to imitate the old ware. The French museums are particularly rich in specimens of old martabani celadon—I would point especially to several large dishes both at Sèvres and in the Musée Guimet. But what is perhaps the finest collection in Europe of celadon and other old wares is now to be seen in the museum at Gotha. It was brought together by the late Duke of Edinburgh, who added to previous acquisitions the collection formed in China by Dr. Hirth.

Yuan Dynasty (1280-1368)Probably at no period during its long history has the Chinese empire been subjected to such a thorough shaking up, to such a complete upsetting and reversal of its ancient ways, as during the advance of the Mongols from the north to the south during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. When they had at length subdued the whole land, there was a moment during the rule of the liberal-minded Kublai Khan when the old barriers and prejudices seemed to have been broken down, and when the Middle Kingdom appeared to be about to enter the general comity of nations. This is what gives to Marco Polo’s account of the country, which he visited at the time, so very ‘un-Chinese’ an air. We hear of Italian friars and French goldsmiths at the court, and of projected embassies from the Pope. Still closer were the relations with the Mohammedan people of Western Asia, then ruled by members of Kublai’s family. Marco Polo, we know, formed part of the escort of Kublai’s sister, when she travelled by sea to Persia to become the bride of the Mongol khan of that country; and a predecessor of this latter ruler, Hulugu, as early as the middle of the thirteenth century, brought over, it is said, as many as a thousand Chinese artificers and settled them in Persia.

And yet when scarcely two generations later the degenerate descendants of Kublai were driven from the imperial throne and replaced by a native dynasty, what slight permanent trace do we see of all these changes reflected in the arts of the Middle Kingdom! No doubt, on looking closely, we should find that a change had taken place during these years: new materials had been brought in, new forms and new decorations applied to the metal ware and the pottery of the Chinese. It is in connection with these two arts especially (and we may add to them the designs on textile fabrics) that we find so many points of interest in the mutual influence of the civilisations of China and Persia at this time. We must remember that in the thirteenth century the craftsman of Persia, as the inheritor of both Saracenic and older traditions, was in many respects ahead of his rival artist in China.

As far as the potter’s art was concerned this was the first meeting of two contrasted schools, which between them cover pretty well the whole field of ceramics—of that part at least of the field in which the glaze is the principal element in the decoration.35

The Persian ware of this time was the culminating example of an art that had been handed down from the Egyptians and the Assyrians. As a rule, among these races, the baser nature of the paste had been concealed by a more or less opaque coating either of a fine clay or ‘slip,’ or of a glaze rendered non-transparent by the addition of tin; it is on this coating that the decoration is painted, to be covered subsequently (in the first case at least, that of the slip ware) by a coating of glaze. It is to this large class, for the most part to the latter or stanniferous division, that nearly all the famous wares of the European renaissance belong, not only the Spanish and Italian majolica but the enamelled fayence of France and Holland as well. It was with the latter two wares that at a later date the porcelain of China was destined to come into competition. Each of these ceramic schools, the Eastern porcelain and the Western fayence, might in certain points claim advantages over the other, advantages both of a practical and of an æsthetic nature. For example, the glory of the Persian fayence of that day lay in its application to architecture, in the brilliant coating of tiles that covered the walls and the domes of the mosques and dwellings both inside and out. The Chinese have never succeeded in making tiles of any size with their porcelain. When used for the decoration of buildings the porcelain, or rather the earthenware, is always in the form of solid, moulded bricks.