полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 1 (of 9)

These are the reasons which have influenced my judgment on this question. I give them to you, to show you that I am imposed on by a semblance of reason, at least; and not with an expectation of their changing your opinion. You have viewed the subject, I am sure, in all its bearings. You have weighed both questions, with all their circumstances. You make the result different from what I do. The same facts impress us differently. This is enough to make me suspect an error in my process of reasoning, though I am not able to detect it. It is of no consequence; as I have nothing to say in the decision, and am ready to proceed heartily on any other plan which may be adopted, if my agency should be thought useful. With respect to the dispositions of the State, I am utterly uninformed. I cannot help thinking, however, that on a view of all the circumstances, they might be united in either of the plans.

Having written this on the receipt of your letter, without knowing of any opportunity of sending it, I know not when it will go; I add nothing, therefore, on any other subject, but assurances of the sincere esteem and respect with which I am, dear Sir, your friend and servant.

TO COMMODORE JONES

Paris, July 11, 1786.Dear Sir,—I am perfectly ready to transmit to America any accounts or proofs you may think proper. Nobody can wish more that justice be done you, nor is more ready to be instrumental in doing whatever may insure it. It is only necessary for me to avoid the presumption of appearing to decide where I have no authority to do it. I will this evening lodge in the hands of Mr. Grand the original order of the board of treasury, with instructions to receive from you the balance you propose to pay, for which he will give you a receipt on the back of the order. I will confer with you when you please on the affair of Denmark, and am, with very great esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO M. DE CREVECOEUR

Paris, July 11, 1786.Sir,—I have been honored with a letter from M. Delisle, Lieutenant General au bailleage de lain, to which is annexed a postscript from yourself. Being unable to write in French so as to be sure of conveying my true meaning, or perhaps any meaning at all, I will beg of you to interpret what I have now the honor to write.

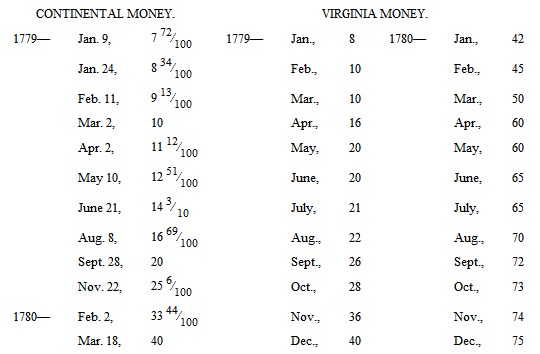

It is time that the United States, generally, and most of the separate States in particular, are endeavoring to establish means to pay the interest of their public debt regularly, and to sink its principal by degrees. But as yet, their efforts have been confined to that part of their debts which is evidenced by certificate. I do not think that any State has yet taken measures for paying their paper money debt. The principle on which it shall be paid I take to be settled, though not directly, yet virtually, by the resolution of Congress of June 3d, 1784; that is, that they will pay the holder, or his representative, what the money was worth at the time he received it, with an interest from that time of six per cent, per annum. It is not said in the letter whether the money received by Barboutin was Continental money; nor is it said at what time it was received. But, that M. Delisle may be enabled to judge what the five thousand three hundred and ninety-eight dollars were worth in hard money when Barboutin received them, I will state to you what was the worth of one hard dollar, both in Continental and Virginia money, through the whole of the years 1779 and 1780, within some part of which it was probably received:

Thus you see that, in January 1779, seven dollars and seventy-two hundredths of a dollar of Continental money were worth one dollar of silver, and at the same time, eight dollars of Virginia paper were worth one dollar of silver, &c. After March 18th, 1780, Continental paper, received in Virginia, will be estimated by the table of Virginia paper. I advise all the foreign holders of paper money to lodge it in the office of their consul for the State where it was received, that he may dispose of it for their benefit the first moment that payment shall be provided by the State or Continent. I had lately the pleasure of seeing the Countess d'Houditot well at Sanois, and have that now of assuring you of the perfect esteem and respect with which I have the honor to be, dear Sir, your most obedient humble servant.

TO THE MARQUIS DE LA FAYETTE

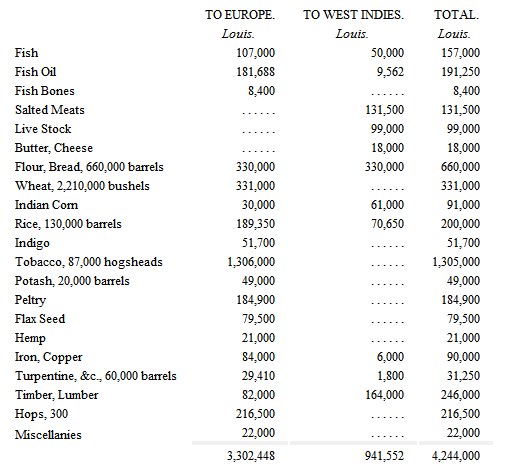

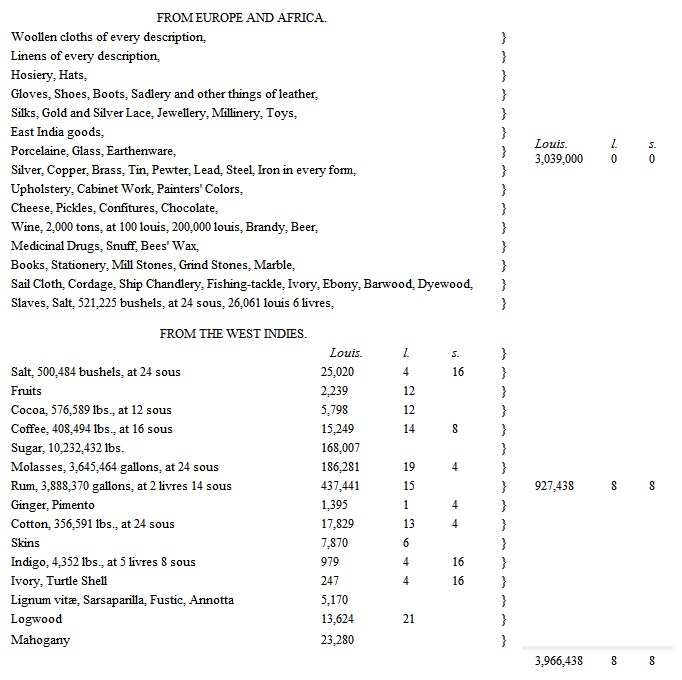

Paris, July 17, 1786.Dear Sir,—I have now the honor of enclosing to you an estimate of the exports and imports of the United States. Calculations of this kind cannot pretend to accuracy, where inattention and fraud combine to suppress their objects. Approximation is all they can aim at. Neither care nor candor have been wanting on my part to bring them as near the truth as my skill and materials would enable me to do. I have availed myself of the best documents from the custom-houses, which have been given to the public, and have been able to rectify these in many instances by information collected by myself on the spot in many of the States. Still remember, however, that I call them but approximations, and that they must present some errors as considerable as they were unavoidable.

Our commerce divides itself into European and West Indian. I have conformed my statement to this division.

On running over the catalogue of American imports, France will naturally mark out those articles with which she could supply us to advantage; and she may safely calculate, that, after a little time shall have enabled us to get rid of our present incumbrances, and of some remains of attachment to the particular forms of manufacture to which we have been habituated, we shall take those articles which she can furnish, on as good terms as other nations, to whatever extent she will enable us to pay for them. It is her interest, therefore, as well as ours, to multiply the means of payment. These must be found in the catalogue of our exports, and among these will be seen neither gold nor silver. We have no mines of either of these metals. Produce, therefore, is all we can offer. Some articles of our produce will be found very convenient to this country for her own consumption. Others will be convenient, as being more commerciable in her hands than those she will give in exchange for them. If there be any which she can neither consume, nor dispose of by exchange, she will not buy them of us, and of course we shall not bring them to her. If American produce can be brought into the ports of France, the articles of exchange for it will be taken in those ports; and the only means of drawing it hither, is to let the merchant see that he can dispose of it on better terms here than anywhere else. If the market price of this country does not in itself offer this superiority, it may be worthy of consideration, whether it should be obtained by such abatements of duties, and even by such other encouragements as the importance of the article may justify. Should some loss attend this in the beginning, it can be discontinued when the trade shall be well established in this channel.

With respect to the West India commerce, I must apprise you that this estimate does not present its present face. No materials have enabled us to say how it stands since the war. We can only show what it was before that period. This is most sensibly felt in the exports of fish and flour. The surplus of the former, which these regulations threw back on us, is forced to Europe, where, by increasing the quantity, it lessens the price; the surplus of the latter is sunk, and to what other objects this portion of industry is turned or turning, I am not able to discover. The imports, too, of sugar and coffee are thrown under great difficulties. These increase the price; and being articles of food for the poorer class (as you may be sensible in observing the quantities consumed), a small increase of price places them above the reach of this class, which being very numerous, must occasion a great diminution of consumption. It remains to see whether the American will endeavor to baffle these new restrictions in order to indulge his habits, or will adopt his habits to other objects which may furnish employment to the surplus of industry formerly occupied in raising that bread which no longer finds a vent in the West Indian market. If, instead of either of these measures, he should resolve to come to Europe for coffee and sugar, he must lessen equivalently his consumption of some other European articles in order to pay for his coffee and sugar, the bread with which he formerly paid for them in the West Indies not being demanded in the European market. In fact, the catalogue of imports offer several articles more dispensable than coffee and sugar. Of all these subjects, the committee and yourself are the more competent judges. To you, therefore, I trust them, with every wish for their improvement; and, with sentiments of that perfect esteem and respect with which I have the honor to be, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

ESTIMATE OF THE EXPORTS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

ESTIMATE OF THE IMPORTS OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO THE GOVERNOR OF VIRGINIA

Paris, July 22, 1786.Sir,—An opportunity offering, at a moment's warning only, to London, I have only time to inform your Excellency that we have shipped from Bordeaux fifteen hundred stand of arms for the State of Virginia, of which I now enclose the bill of lading. A somewhat larger number of cartouch-boxes have been prepared here, are now packing, and will go to Havre immediately to be shipped there. As soon as these are forwarded, I will do myself the honor of sending you a state of the expenditures for these and other objects. The residue of the arms and accoutrements are in a good course of preparation. I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the highest respect, your Excellency's most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO M. CATHALAN

Paris, August 8, 1786.Sir,—I have been duly honored with your favor of July 28. I have in consequence thereof reconsidered the order of Council of Berny, and it appears to me to extend as much to the southern ports of France as to the western; and that for tobacco delivered in any port where there is no manufacture, only thirty sols per quintal is to be deducted. The farmers may perhaps evade the purchase of tobacco in a port convenient to them by purchasing the whole quantity in other ports. I shall readily lend my aid to promote the mercantile intercourse between your port and the United States whenever I can aid it. For the present, it is much restrained by the danger of capture by the piratical States.

I have the honor to be, with much respect, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO GOVERNOR HENRY

Paris, August 9, 1786.Sir,—I have duly received the honor of your Excellency's letter of May 17, 1786, on the subject of Captain Green, supposed to be in captivity with the Algerines. I wish I could have communicated the agreeable news that this supposition was well founded, and I should not have hesitated to gratify as well your Excellency as the worthy father of Captain Green, by doing whatever would have been necessary for his redemption. But we have certainly no such prisoner at Algiers. We have there twenty-one prisoners in all. Of these only four are Americans by birth. Three of these are Captains, of the names of O'Brian, Stephens, and Coffyn. There were only two vessels taken by the Algerines, one commanded by O'Brian, the other by Stephens. Coffyn, I believe, was a supercargo. The Moors took one vessel from Philadelphia, which they gave up again with the crew. No other captures have been made on us by any of the piratical States. I wish I could say we were likely to be secure against future captures. With Morocco I have hope we shall; but the States of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli hold their peace at a price which would be felt by every man in his settlement with the tax-gatherer.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the highest respect, your Excellency's most obedient, and most humble servant.

P. S. August 13, 1786. I have this morning received information from Mr. Barclay that our peace with the Emperor of Morocco would be pretty certainly signed in a few days. This leaves us the Atlantic free. Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, however, remaining hostile, will shut up the Mediterranean to us. The two latter never come into the Atlantic; the Algerines rarely, and but a little way out of the Straits. In Mr. Barclay's letter is this paragraph, "There is a young man now under my care, who has been a slave sometime with the Arabs in the desert." His name is James Mercier, born at the town of Suffolk, Nansemond County, Virginia. The King sent him after the first audience, and I shall take him to Spain. On Mr. Barclay's return to Spain, he shall find there a letter from me to forward this young man to his own country, for the expenses of which I will make myself responsible.

TO JOHN JAY

Paris, August 11, 1786.Sir,—Since the date of my last, which was of July the 8th, I have been honored with the receipt of yours of June the 16th. I am to thank you on the part of the minister of Geneva for the intelligence it contained on the subject of Gallatin, whose relations will be relieved by the receipt of it.

The inclosed intelligence, relative to the instructions of the court of London to Sir Guy Carleton, came to me through the Count de La Touche, and Marquis de La Fayette. De La Touche is a director under the Marechal de Castries, minister for the marine department, and possibly receives his intelligence from him, and he from their ambassador at London. Possibly, too, it might be fabricated here. Yet, weighing the characters of the ministry of St. James's and Versailles, I think the former more capable of giving such instructions, than the latter of fabricating them for the small purposes the fabrication could answer.

The Gazette of France, of July the 28th, announces the arrival of Peyrouse at Brazil, that he was to touch at Otaheite, and proceed to California, and still further northwardly. This paper, as you well know, gives out such facts as the court are willing the world should be possessed of. The presumption is, therefore, that they will make an establishment of some sort, on the north-west coast of America.

I trouble you with the copy of a letter from Scheveighauser and Dobrec, on a subject with which I am quite unacquainted. Their letter to Congress of November the 30th, 1780, gives their state of the matter. How far it be true and just can probably be ascertained from Dr. Franklin, Dr. Lee, and other gentlemen now in America. I shall be glad to be honored with the commands of Congress on this subject. I have inquired into the state of their arms, mentioned in their letter to me. The principal articles were about thirty thousand bayonets, fifty thousand gunlocks, thirty cases of arms, twenty-two cases of sabres, and some other things of little consequence. The quay at Nantes, having been overflowed by the river Loire, the greatest part of these arms were under water, and they are now, as I am informed, a solid mass of rust, not worth the expense of throwing them out of the warehouse, much less that of storage. Were not their want of value a sufficient reason against reclaiming the property of these arms, it rests with Congress to decide, whether other reasons are not opposed to this reclamation. They were the property of a sovereign body, they were seized by an individual, taken cognizance of by a court of justice, and refused, or at least not restored by the sovereign within whose States they had been arrested. These are circumstances which have been mentioned to me. Dr. Franklin, however, will be able to inform Congress, with precision, as to what passed on this subject. If the information I have received be anything like the truth, the discussion of this matter can only be with the court of Versailles. It would be very delicate, and could have but one of two objects; either to recover the arms, which are not worth receiving, or to satisfy us on the point of honor. Congress will judge how far the latter may be worth pursuing against a particular ally, and under actual circumstances. An instance, too, of acquiescence on our part under a wrong, rather than disturb our friendship by altercations, may have its value in some future case. However, I shall be ready to do in this what Congress shall be pleased to direct.

I enclose the despatches relative to the Barbary negotiation, received since my last. It is painful to me to overwhelm Congress and yourself continually with these voluminous papers. But I have no right to suppress any part of them, and it is one of those cases where, from a want of well-digested information, we must be contented to examine a great deal of rubbish, in order to find a little good matter.

The gazettes of Leyden and France, to the present date, accompany this, which, for want of direct and safe opportunities, I am obliged to send by an American gentleman, by the way of London. The irregularity of the French packets has diverted elsewhere the tide of passengers, who used to furnish me occasions of writing to you, without permitting my letters to go through the post office. So that when the packets go now, I can seldom write by them.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the highest esteem and respect, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

[The annexed is a translation of the paper referred to in the preceding letter, on the subject of the instructions given to Sir Guy Carleton.]

An extract of English political news, concerning North America. July 14th, 1786.

General Carleton departs in a few days with M. de La Naudiere, a Canadian gentleman. He has made me acquainted with the Indian, Colonel Joseph Brandt. It is certain that he departs with the most positive instructions to distress the Americans as much as possible, and to create them enemies on all sides.

Colonel Brandt goes loaded with presents for himself, and for several chiefs of the tribes bordering on Canada. It would be well for the Americans to know in time, that enemies are raised against them, in order to derange their system of government, and to add to the confusion which already exists in it. The new possessions of England will not only gain what America shall lose, but will acquire strength in proportion to the weakening of the United States.

Sooner or later, the new States which are forming will place themselves under the protection of England, which can always communicate with them through Canada; and which, in case of future necessity, can harass the United States on one side by her shipping, and on the other by her intrigues. This system has not yet come to maturity, but it is unfolded, and we may rely upon the instructions given to Colonel Brandt.

TO COLONEL MONROE

Paris, August 11, 1786.Dear Sir,—I wrote you last on the 9th of July; and, since that, have received yours of the 16th of June, with the interesting intelligence it contained. I was entirely in the dark as to the progress of that negotiation, and concur entirely in the views you have taken of it. The difficulty on which it hangs is a sine qua non with us. It would be to deceive them and ourselves, to suppose that an amity can be preserved, while this right is withheld. Such a supposition would argue, not only an ignorance of the people to whom this is most interesting, but an ignorance of the nature of man, or an inattention to it. Those who see but half way into our true interest, will think that that concurs with the views of the other party. But those who see it in all its extent, will be sensible that our true interest will be best promoted, by making all the just claims of our fellow citizens, wherever situated, our own, by urging and enforcing them with the weight of our whole influence, and by exercising in this, as in every other instance, a just government in their concerns, and making common cause even where our separate interest would seem opposed to theirs. No other conduct can attach us together; and on this attachment depends our happiness.

The King of Prussia still lives, and is even said to be better. Europe is very quiet at present. The only germ of dissension, which shows itself at present, is in the quarter of Turkey. The Emperor, the Empress, and the Venetians seem all to be picking at the Turks. It is not probable, however, that either of the two first will do anything to bring on an open rupture, while the King of Prussia lives.

You will perceive, by the letters I enclose to Mr. Jay, that Lambe, under the pretext of ill health, declines returning either to Congress, Mr. Adams, or myself. This circumstance makes me fear some malversation. The money appropriated to this object being in Holland, and, having been always under the care of Mr. Adams, it was concerted between us that all the drafts should be on him. I know not, therefore, what sums may have been advanced to Lambe; I hope, however, nothing great. I am persuaded that an angel sent on this business, and so much limited in his terms, could have done nothing. But should Congress propose to try the line of negotiation again, I think they will perceive that Lambe is not a proper agent. I have written to Mr. Adams on the subject of a settlement with Lambe. There is little prospect of accommodation between the Algerines, and the Portuguese and Neapolitans. A very valuable capture, too, lately made by them on the Empress of Russia, bids fair to draw her on them. The probability is, therefore, that these three nations will be at war with them, and the probability is, that could we furnish a couple of frigates, a convention might be formed with those powers, establishing a perpetual cruise on the coast of Algiers, which would bring them to reason. Such a convention, being left open to all powers willing to come into it, should have for its object a general peace, to be guaranteed to each, by the whole. Were only two or three to begin a confederacy of this kind, I think every power in Europe would soon fall into it, except France, England, and perhaps Spain and Holland. Of these, there is only England, who would give any real aid to the Algerines. Morocco, you perceive, will be at peace with us. Were the honor and advantage of establishing such a confederacy out of the question, yet the necessity that the United States should have some marine force, and the happiness of this, as the ostensible cause for beginning it, would decide on its propriety. It will be said, there is no money in the treasury. There never will be money in the treasury, till the confederacy shows its teeth. The States must see the rod; perhaps it must be felt by some one of them. I am persuaded, all of them would rejoice to see every one obliged to furnish its contributions. It is not the difficulty of furnishing them, which beggars the treasury, but the fear that others will not furnish as much. Every rational citizen must wish to see an effective instrument of coercion, and should fear to see it on any other element than the water. A naval force can never endanger our liberties, nor occasion bloodshed; a land force would do both. It is not in the choice of the States, whether they will pay money to cover their trade against the Algerines. If they obtain a peace by negotiation, they must pay a great sum of money for it; if they do nothing, they must pay a great sum of money, in the form of insurance; and in either way, as great a one as in the way of force, and probably less effectual.

I look forward with anxiety to the approaching moment of your departure from Congress. Besides the interest of the confederacy and of the State, I have a personal interest in it. I know not to whom I may venture confidential communications, after you are gone. I take the liberty of placing here my respects to Mrs. Monroe, and assurances of the sincere esteem with which I am, dear Sir, your friend and servant.