полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 1 (of 9)

And that they may be the better informed of our sentiments, touching the conduct we wish them to observe on this important occasion, we desire that they will express, in the first place, our faith and true allegiance to his Majesty, King George the third, our lawful and rightful sovereign; and that we are determined, with our lives and fortunes, to support him in the legal exercise of all his just rights and prerogatives. And, however misrepresented, we sincerely approve of a constitutional connection with Great Britain, and wish, most ardently, a return of that intercourse of affection and commercial connection, that formerly united both countries, which can only be effected by a removal of those causes of discontent, which have of late unhappily divided us.

It cannot admit of a doubt, but the British subjects in America are entitled to the same rights and privileges as their fellow subjects possess in Britain; and therefore, that the power assumed by the British Parliament to bind America by their statutes in all cases whatsoever, is unconstitutional, and the source of these unhappy differences.

The end of government would be defeated by the British Parliament exercising a power over the lives, the property, and the liberty of American subjects, who are not, and, from their local circumstances, cannot be, there represented. Of this nature, we consider the several acts of Parliament for raising a revenue in America, for extending the jurisdiction of the courts of Admiralty, for seizing American subjects, and transporting them to Britain to be tried for crimes committed in America, and the several late oppressive acts respecting the town of Boston, and Province of the Massachusetts Bay.

The original constitution of the American colonies possessing their assemblies with the sole right of directing their internal polity, it is absolutely destructive of the end of their institution, that their legislatures should be suspended, or prevented, by hasty dissolutions, from exercising their legislative powers.

Wanting the protection of Britain, we have long acquiesced in their acts of navigation, restrictive of our commerce, which we consider as an ample recompense for such protection; but as those acts derive their efficacy from that foundation alone, we have reason to expect they will be restrained, so as to produce the reasonable purposes of Britain, and not injurious to us.

To obtain redress of these grievances, without which the people of America can neither be safe, free, nor happy, they are willing to undergo the great inconvenience that will be derived to them, from stopping all imports whatever, from Great Britain, after the first day of November next, and also to cease exporting any commodity whatsoever, to the same place, after the tenth day of August, 1775. The earnest desire we have to make as quick and full payment as possible of our debts to Great Britain, and to avoid the heavy injury that would arise to this country from an earlier adoption of the non-exportation plan, after the people have already applied so much of their labor to the perfecting of the present crop, by which means, they have been prevented from pursuing other methods of clothing and supporting their families, have rendered it necessary to restrain you in this article of non-exportation; but it is our desire, that you cordially co-operate with our sister colonies in General Congress, in such other just and proper methods as they, or the majority, shall deem necessary for the accomplishment of these valuable ends.

The proclamation issued by General Gage, in the government of the Province of the Massachusetts Bay, declaring it treason for the inhabitants of that province to assemble themselves to consider of their grievances, and form associations for their common conduct on the occasion, and requiring the civil magistrates and officers to apprehend all such persons, to be tried for their supposed offences, is the most alarming process that ever appeared in a British government; and the said General Gage hath, thereby, assumed, and taken upon himself, powers denied by the constitution to our legal sovereign; that he, not having condescended to disclose by what authority he exercises such extensive and unheard of powers, we are at a loss to determine, whether he intends to justify himself as the representative of the King, or as the Commander-in-Chief of his Majesty's forces in America. If he considers himself as acting in the character of his Majesty's representative, we would remind him that the statute 25th, Edward the third has expressed and defined all treasonable offences, and that the legislature of Great Britain had declared, that no offence shall be construed to be treason, but such as is pointed out by that statute, and that this was done to take out of the hands of tyrannical Kings, and of weak and wicked Ministers, that deadly weapon, which constructive treason had furnished them with, and which had drawn the blood of the best and honestest men in the kingdom; and that the King of Great Britain hath no right by his proclamation, to subject his people to imprisonment, pains, and penalties.

That if the said General Gage conceives he is empowered to act in this manner, as the Commander-in-Chief of his Majesty's forces in America, this odious and illegal proclamation must be considered as a plain and full declaration, that this despotic Viceroy will be bound by no law, nor regard the constitutional rights of his Majesty's subjects, whenever they interfere with the plan he has formed for oppressing the good people of the Massachusetts Bay; and, therefore, that the executing, or attempting to execute, such proclamations, will justify resistance and reprisal.

[Note E.]

Monticello, November 1. 1778.Dear Sir,

I have got through the bill for "proportioning crimes and punishments in cases heretofore capital," and now enclose it to you with a request that you will be so good, as scrupulously to examine and correct it, that it may be presented to our committee with as few defects as possible. In its style, I have aimed at accuracy, brevity, and simplicity, preserving, however, the very words of the established law, wherever their meaning had been sanctioned by judicial decisions, or rendered technical by usage. The same matter, if couched in the modern statutory language, with all its tautologies, redundancies, and circumlocutions, would have spread itself over many pages, and been unintelligible to those whom it most concerns. Indeed, I wished to exhibit a sample of reformation in the barbarous style into which modern statutes have degenerated from their ancient simplicity. And I must pray you to be as watchful over what I have not said, as what is said; for the omissions of this bill have all their positive meaning. I have thought it better to drop, in silence, the laws we mean to discontinue, and let them be swept away by the general negative words of this, than to detail them in clauses of express repeal. By the side of the text I have written the notes I made, as I went along, for the benefit of my own memory. They may serve to draw your attention to questions, to which the expressions or the omissions of the text may give rise. The extracts from the Anglo-Saxon laws, the sources of the Common law, I wrote in their original, for my own satisfaction;28 but I have added Latin, or liberal English translations. From the time of Canute to that of the Magna Charta, you know, the text of our statutes is preserved to us in Latin only, and some old French.

I have strictly observed the scale of punishments settled by the Committee, without being entirely satisfied with it. The Lex talionis, although a restitution of the Common law, to the simplicity of which we have generally found it so advantageous to return, will be revolting to the humanized feelings of modern times. An eye for an eye, and a hand for a hand, will exhibit spectacles in execution whose moral effect would be questionable; and even the membrum pro membro of Bracton, or the punishment of the offending member, although long authorized by our law, for the same offence in a slave has, you know, been not long since repealed, in conformity with public sentiment. This needs reconsideration.

I have heard little of the proceedings of the Assembly, and do not expect to be with you till about the close of the month. In the meantime, present me respectfully to Mrs. Wythe, and accept assurances of the affectionate esteem and respect of, dear Sir,

Your friend and servant.George Wythe, Esq.

A Bill for proportioning Crimes and Punishments, in cases heretofore Capital

Whereas, it frequently happens that wicked and dissolute men, resigning themselves to the dominion of inordinate passions, commit violations on the lives, liberties, and property of others, and, the secure enjoyment of these having principally induced men to enter into society, government would be defective in its principal purpose, were it not to restrain such criminal acts, by inflicting due punishments on those who perpetrate them; but it appears, at the same time, equally deducible from the purposes of society, that a member thereof, committing an inferior injury, does not wholly forfeit the protection of his fellow citizens, but, after suffering a punishment in proportion to his offence, is entitled to their protection from all greater pain, so that it becomes a duty in the legislature to arrange, in a proper scale, the crimes which it may be necessary for them to repress, and to adjust thereto a corresponding gradation of punishments.

And whereas, the reformation of offenders, though an object worthy the attention of the laws, is not effected at all by capital punishments, which exterminate instead of reforming, and should be the last melancholy resource against those whose existence is become inconsistent with the safety of their fellow citizens, which also weaken the State, by cutting off so many who, if reformed, might be restored sound members to society, who, even under a course of correction, might be rendered useful in various labors for the public, and would be living and long-continued spectacles to deter others from committing the like offences.

And forasmuch as the experience of all ages and countries hath shown, that cruel and sanguinary laws defeat their own purpose, by engaging the benevolence of mankind to withhold prosecutions, to smother testimony, or to listen to it with bias, when, if the punishment were only proportioned to the injury, men would feel it their inclination, as well as their duty, to see the laws observed.

For rendering crimes and punishments, therefore, more proportionate to each other:

Be it enacted by the General Assembly, that no crime shall be henceforth punished by the deprivation of life or limb,29 except those hereinafter ordained to be so punished.

30If a man do levy war31 against the Commonwealth [in the same], or be adherent to the enemies of the Commonwealth [within the same],32 giving to them aid or comfort in the Commonwealth, or elsewhere, and thereof be convicted of open deed, by the evidence of two sufficient witnesses, or his own voluntary confession, the said cases, and no33 others, shall be adjudged treasons which extend to the Commonwealth, and the person so convicted shall suffer death, by hanging,34 and shall forfeit his lands and goods to the Commonwealth.

If any person commit petty treason, or a husband murder his wife, a parent35 his child, or a child his parent, he shall suffer death by hanging, and his body be delivered to Anatomists to be dissected.

Whosoever committeth murder by poisoning shall suffer death by poison.

Whosoever committeth murder by way of duel shall suffer death by hanging; and if he were the challenger, his body, after death, shall be gibbetted.36 He who removeth it from the gibbet shall be guilty of a misdemeanor; and the officer shall see that it be replaced.

Whosoever shall commit murder in any other way shall suffer death by hanging.

And in all cases of Petty treason and murder, one half of the lands and goods of the offender, shall be forfeited to the next of kin to the person killed, and the other half descend and go to his own representatives. Save only, where one shall slay the challenger in a duel,37 in which case, no part of his lands or goods shall be forfeited to the kindred of the party slain, but, instead thereof, a moiety shall go to the Commonwealth.

The same evidence38 shall suffice, and order and course39 of trial be observed in cases of Petty treason, as in those of other40 murders.

Whosoever shall be guilty of manslaughter,41 shall, for the first offence, be condemned to hard42 labor for seven years in the public works, shall forfeit one half of his lands and goods to the next of kin to the person slain; the other half to be sequestered during such term, in the hands and to the use of the Commonwealth, allowing a reasonable part of the profits for the support of his family. The second offence shall be deemed murder.

And where persons, meaning to commit a trespass43 only, or larceny, or other unlawful deed, and doing an act from which involuntary homicide hath ensued, have heretofore been adjudged guilty of manslaughter, or of murder, by transferring such their unlawful intention to an act, much more penal than they could have in probable contemplation; no such case shall hereafter be deemed manslaughter, unless manslaughter was intended, nor murder, unless murder was intended.

In other cases of homicide, the law will not add to the miseries of the party, by punishments and forfeitures.44

Whenever sentence of death shall have been pronounced against any person for treason or murder, execution shall be done on the next day but one after such sentence, unless it be Sunday, and then on the Monday following.45

Whosoever shall be guilty of Rape,46 Polygamy,47 or Sodomy48 with man or woman, shall be punished, if a man, by castration,49 if a woman, by cutting through the cartilage of her nose a hole of one half inch in diameter at the least.

But no one shall be punished for Polygamy, who shall have married after probable information of the death of his or her husband or wife, or after his or her husband or wife, hath absented him or herself, so that no notice of his or her being alive hath reached such person for seven years together, or hath suffered the punishments before prescribed for rape, polygamy, or sodomy.

Whosoever on purpose, and of malice forethought, shall maim50 another, or shall disfigure him, by cutting out or disabling the tongue, slitting or cutting off a nose, lip, or ear, branding, or otherwise, shall be maimed, or disfigured in like51 sort: or if that cannot be, for want of the same part, then as nearly as may be, in some other part of at least equal value and estimation, in the opinion of a jury, and moreover, shall forfeit one half of his lands and goods to the sufferer.

Whosoever shall counterfeit52 any coin, current by law within this Commonwealth, or any paper bills issued in the nature of money, or of certificates of loan on the credit of this Commonwealth, or of all or any of the United States of America, or any Inspectors' notes for tobacco, or shall pass any such counterfeit coin, paper, bills, or notes, knowing them to be counterfeit; or, for the sake of lucre, shall diminish,53 case, or wash any such coin, shall be condemned to hard labor six years in the public works, and shall forfeit all his lands and goods to the Commonwealth.

54Whosoever committeth Arson, shall be condemned to hard labor five years in the public works, and shall make good the loss of the sufferers threefold.55

If any person shall, within this Commonwealth, or being a citizen thereof, shall without the same, wilfully destroy,56 or run57 away with any sea-vessel, or goods laden on board thereof, or plunder or pilfer any wreck, he shall be condemned to hard labor five years in the public works, and shall make good the loss of the sufferers threefold.

Whosoever committeth Robbery,58 shall be condemned to hard labor four years in the public works, and shall make double reparation to the persons injured.

Whatsoever act, if committed on any Mansion house, would be deemed Burglary,59 shall be Burglary, if committed on any other house; and he, who is guilty of Burglary, shall be condemned to hard labor four years in the public works, and shall make double reparation to the persons injured.

Whatsoever act, if committed in the night time, shall constitute the crime of Burglary, shall, if committed in the day, be deemed House-breaking;60 and whosoever is guilty thereof, shall be condemned to hard labor three years in the public works, and shall make reparation to the persons injured.

Whosoever shall be guilty of Horse-stealing,61 shall be condemned to hard labor three years in the public works, and shall make reparation to the person injured.

Grand Larceny62 shall be where the goods stolen are of the value of five dollars; and whosoever shall be guilty thereof, shall be forthwith put in the pillory for one half hour, shall be condemned to hard labor63 two years in the public works, and shall make reparation to the person injured.

Petty Larceny shall be, where the goods stolen are of less value than five dollars; and whosoever shall be guilty thereof, shall be forthwith put in the pillory for a quarter of an hour, shall be condemned to hard labor one year in the public works, and shall make reparation to the person injured.

Robbery64 or larceny of bonds, bills obligatory, bills of exchange, or promissory notes for the payment of money or tobacco, lottery tickets, paper bills issued in the nature of money, or of certificates of loan on the credit of this Commonwealth, or of all or any of the United States of America, or Inspectors' notes for tobacco, shall be punished in the same manner as robbery or larceny of the money or tobacco due on, or represented by such papers.

Buyers65 and receivers of goods taken by way of robbery or larceny, knowing them to have been so taken, shall be deemed accessaries to such robbery or larceny after the fact.

Prison-breakers66, also, shall be deemed accessaries after the fact, to traitors or felons whom they enlarge from prison.67

All attempts to delude the people, or to abuse their understanding by exercise of the pretended arts of witchcraft, conjuration, enchantment, or sorcery, or by pretended prophecies, shall be punished by ducking and whipping, at the discretion of a jury, not exceeding fifteen stripes.68

If the principal offenders be fled,69 or secreted from justice, in any case not touching life or member, the accessaries may, notwithstanding, be prosecuted as if their principal were convicted.70

If any offender stand mute of obstinacy,71 or challenge peremptorily more of the jurors than by law he may, being first warned of the consequence thereof, the court shall proceed as if he had confessed the charge.72

Pardon and Privilege of clergy, shall henceforth be abolished, that none may be induced to injure through hope of impunity. But if the verdict be against the defendant, and the court before whom the offence is heard and determined, shall doubt that it may be untrue for defect of testimony, or other cause, they may direct a new trial to be had.73

No attainder shall work corruption of blood in any case.

In all cases of forfeiture, the widow's dower shall be saved to her, during her title thereto; after which it shall be disposed of as if no such saving had been.

The aid of Counsel,74 and examination of their witnesses on oath, shall be allowed to defendants in criminal prosecutions.

Slaves guilty of any offence75 punishable in others by labor in the public works, shall be transported to such parts in the West Indies, South America, or Africa, as the Governor shall direct, there to be continued in slavery.

[Note F.]

Notes on the Establishment of a Money Unit, and of a Coinage for the United StatesIn fixing the Unit of Money, these circumstances are of principal importance.

I. That it be of convenient size to be applied as a measure to the common money transactions of life.

II. That its parts and multiples be in an easy proportion to each other, so as to facilitate the money arithmetic.

III. That the Unit and its parts, or divisions, be so nearly of the value of some of the known coins, as that they may be of easy adoption for the people.

The Spanish Dollar seems to fulfil all these conditions.

I. Taking into our view all money transactions, great and small, I question if a common measure of more convenient size than the Dollar could be proposed. The value of 100, 1000, 10,000 dollars is well estimated by the mind; so is that of the tenth or the hundredth of a dollar. Few transactions are above or below these limits. The expediency of attending to the size of the money Unit will be evident, to any one who will consider how inconvenient it would be to a manufacturer or merchant, if, instead of the yard for measuring cloth, either the inch or the mile had been made the Unit of Measure.

II. The most easy ratio of multiplication and division, is that by ten. Every one knows the facility of Decimal Arithmetic. Every one remembers, that, when learning Money-Arithmetic, he used to be puzzled with adding the farthings, taking out the fours and carrying them on; adding the pence, taking out the twelves and carrying them on; adding the shillings, taking out the twenties and carrying them on; but when he came to the pounds, where he had only tens to carry forward, it was easy and free from error. The bulk of mankind are school-boys through life. These little perplexities are always great to them. And even mathematical heads feel the relief of an easier, substituted for a more difficult process. Foreigners, too, who trade and travel among us, will find a great facility in understanding our coins and accounts from this ratio of subdivision. Those who have had occasion to convert the livres, sols, and deniers of the French; the gilders, stivers, and frenings of the Dutch; the pounds, shillings, pence, and farthings of these several States, into each other, can judge how much they would have been aided, had their several subdivisions been in a decimal ratio. Certainly, in all cases, where we are free to choose between easy and difficult modes of operation, it is most rational to choose the easy. The Financier, therefore, in his report, well proposes that our Coins should be in decimal proportions to one another. If we adopt the Dollar for our Unit, we should strike four coins, one of gold, two of silver, and one of copper, viz.:

1. A golden piece, equal in value to ten dollars:

2. The Unit or Dollar itself, of silver:

3. The tenth of a Dollar, of silver also:

4. The hundredth of a Dollar, of copper.

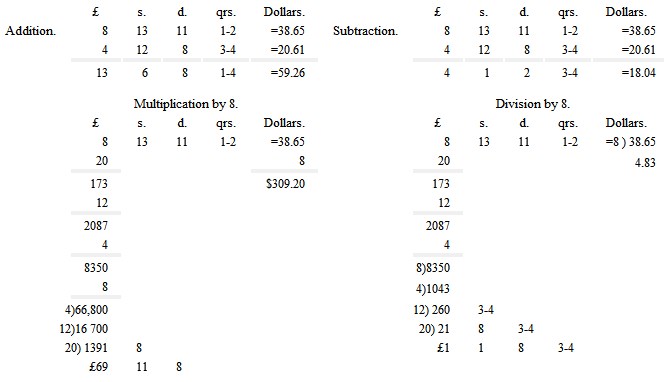

Compare the arithmetical operations, on the same sum of money expressed in this form, and expressed in the pound sterling and its division.

A bare inspection of the above operations will evince the labor which is occasioned by subdividing the Unit into 20ths, 240ths, and 960ths, as the English do, and as we have done; and the ease of subdivision in a decimal ratio. The same difference arises in making payment. An Englishman, to pay £8, 13s. 11d. 1-2 qrs., must find, by calculation, what combination of the coins of his country will pay this sum; but an American, having the same sum to pay, thus expressed $38.65, will know, by inspection only, that three golden pieces, eight units or dollars, six tenths, and five coppers, pay it precisely.

III. The third condition required is, that the Unit, its multiples, and subdivisions, coincide in value with some of the known coins so nearly, that the people may, by a quick reference in the mind, estimate their value. If this be not attended to, they will be very long in adopting the innovation, if ever they adopt it. Let us examine, in this point of view, each of the four coins proposed.

1. The golden piece will be 1-5 more than a half joe, and 1-15 more than a double guinea. It will be readily estimated, then, by reference to either of them; but more readily and accurately as equal to ten dollars.

2. The Unit, or Dollar, is a known coin, and the most familiar of all, to the minds of the people. It is already adopted from South to North; has identified our currency, and therefore happily offers itself as a Unit already introduced. Our public debt, our requisitions, and their appointments, have given it actual and long possession of the place of Unit. The course of our commerce, too, will bring us more of this than of any other foreign coin, and therefore renders it more worthy of attention. I know of no Unit which can be proposed in competition with the Dollar, but the Pound. But what is the Pound? 1547 grains of fine silver in Georgia; 1289 grains in Virginia, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire; 1031 1-4 grains in Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey; 966 3-4 grains in North Carolina and New York. Which of these shall we adopt? To which State give that pre-eminence of which all are so jealous? And on which impose the difficulties of a new estimate of their corn, their cattle, and other commodities? Or shall we hang the pound sterling, as a common badge, about all their necks? This contains 1718 3-4 grains of pure silver. It is difficult to familiarize a new coin to the people; it is more difficult to familiarize them to a new coin with an old name. Happily, the dollar is familiar to them all, and is already as much referred to for a measure of value, as their respective provincial pounds.