полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, Vol II

To invade Great Britain there had first to be concentrated round a chosen point the great armies required to insure success, and the very large number of vessels needed to transport them. Other corps, more or less numerous, destined to further the principal movement by diversions in different directions, distracting the enemy's attention, might embark at distant ports and sail independently of the main body; but for the latter it was necessary to start together and land simultaneously, in mass, at a given point of the English coast. To this principal effort Bonaparte destined one hundred and thirty thousand men; of whom one hundred thousand should form the first line and embark at the same hour from four different ports, which lay within a length of twenty miles on the Channel coast. The other thirty thousand constituted the reserve, and were to sail shortly after the first.

To carry any such force at once, in ordinary sea-going vessels of that day, was impracticable. The requisite number could not be had, and there was no French Channel port where they could safely lie. Even were these difficulties overcome, and the troops embarked together, the mere process of getting under way would entail endless delays, the vessels dependent upon sail could not keep together, and the only conditions of wind under which they could move at all would expose them to be scattered and destroyed by the British navy, which would have the same power of motion, and to which Bonaparte could oppose no equal force. The very gathering of so many helpless sailing transports would betray the place where the French navy must concentrate, and where therefore the hostile ships would assemble at the first indication of a combined movement. Finally, such transports must anchor at some distance from the British coast and the troops land from them in boats, an additional operation both troublesome and dangerous.

For these reasons the crossing must be made in vessels not dependent upon sail alone, but capable of being moved by oars. They must therefore be small and of very light draught, which would allow them to shelter in the shallow French harbors and be beached upon reaching the English coast, so that the troops could land directly from them. It was possible that a number of such vessels once started, and favored by fog or calm, might pass unseen, or even in defiance of the enemy's ships-of-war, lying helpless to attack through want of wind. It was upon this possibility that Bonaparte sought to fix the attention of the British government. As the occupation of Taranto and the movements in Italy were designed to divert Nelson's attention to the Levant, so the ostentatious preparation of the great flotilla to pass unsupported was meant to conceal the real purpose of supporting it. To concentrate the apprehensions of the British authorities upon the flotilla, to draw their eyes away from the naval ports in which lay the French squadrons, and then to unite the latter in the Channel, controlling it for a measurable time by a great fleet, was the grand combination by which Bonaparte hoped to insure the triumphant crossing of the army and the conquest of England. He kept it, however, in his own breast; a profound secret only gradually revealed to the very few men intrusted with its execution.

To create and organize the flotilla and the army of invasion was the first task. Preparations so extensive and rapid demanded all the resources of France. To build at the same time the thousand and more of boats, each of which should carry from sixty to a hundred soldiers, besides from two to four heavy cannon for its own defence, overpassed the powers of any single port. Far in the interior of France, on the banks of the numerous streams running toward the Channel and the Bay of Biscay, as well as in all the little coast harbors themselves, hosts of men were busily working. The North Sea and Holland were also required to furnish their quota. At the same time measures were taken to facilitate their passage in safety to the point of concentration, which was fixed at Boulogne, and to harbor them commodiously upon arrival. They could from their light draught run close along shore, and from their construction be beached without harm. Within easy gunshot of the coast, therefore, lay the road they followed in their passages, which were commonly made in bodies of thirty to sixty, and from port to port, till the journey's end. To support the movements, sea-coast batteries were established at short intervals; under which, if hard pressed, they could take refuge. In addition there were organized in each maritime district batteries of field artillery, which stood ready to drive at once to the scene of action in case the enemy attacked. "One field-gun to every league of coast is the least allowance," wrote Bonaparte. In the early months of the war great importance was attached by the British to harassing these voyages and impeding the concentration, but the attempt was soon abandoned. The boats, if endangered, anchored under the nearest guns, infantry and horse-artillery summoned by the coast-telegraph hurried to the scene, and the enemy's vessels soon found the combined resistance too strong. Ordinarily, indeed, the coastwise movement of a division of the flotilla was a concerted operation, in which all the arms, afloat and ashore, assisted. In extreme cases the vessels were beached, and British seamen fought hand to hand with French soldiers for possession; rarely, however, with success. "The cause of our flotilla not having succeeded in destroying the gun-vessels of the enemy," wrote Lord St. Vincent, "did not arise from their draught of water, but from the powerful batteries on the coast." The concentration, though accomplished less swiftly than Bonaparte's eagerness demanded, was little impeded by the British.

The port of Boulogne, near the eastern end of the English Channel, lies on a strip of coast which runs due south from the Straits of Dover to the mouth of the Somme, a distance of about fifty miles. It is a tidal harbor, the mouth of a little river called the Liane, on the north side of which the town is built. In it even boats of small draught then lay aground at low water; and its capacity at high water was limited. Extensive excavations were therefore ordered to be made by the soldiers encamped in the neighborhood, who received extra wages for the work. When finished, the port presented a double basin; the outer, oblong, bordering the river bed on either side of the channel, which was left clear; the inner of semi-circular form, dug out of the flats opposite the town and connected with the former by a narrow passage. Both were lined with quays, alongside which the vessels of the flotilla lay in tiers, sometimes nine deep; and in July, 1805, when the hour for the last and greatest of Napoleon's naval combinations was at hand, and Trafalgar itself in the near distance, Boulogne sheltered over a thousand gunboats and transports ready to carry forty thousand men to the shores of England. North and south, not only the neighborhood of the harbor but the whole coast bristled with cannon; and opposite the entrance rose a powerful work, built upon piles, to protect the vessels when going out and also when anchored outside. For here was one of the great difficulties of the undertaking. So many boats could not pass out through the narrow channel during one high water. Two tides at the least, that is, twenty-four hours, were needed, granting the most perfect organization and most accurate movement. Half of the flotilla therefore must lie outside for some hours; and it was not to be expected that the British cruisers would allow so critical a moment to pass unimproved, unless deterred by the protection which the foresight of Bonaparte had provided.

North of Boulogne and within five miles of it were two other much smaller harbors, likewise tidal, called Vimereux and Ambleteuse; and to the south, twelve miles distant, a third, named Étaples. Though insignificant, the impossibility of enlarging Boulogne to hold the whole flotilla compelled Bonaparte to develop these, and they together held some seven hundred more gun-vessels and transports. From the three, sixty-two thousand soldiers were to embark; and from each of the four ports a due proportion of field artillery, ammunition and other supplies were to go forward. Some six thousand horses were also to be transported; but the greater part of the cavalry took only their saddles and bridles, looking to find mounts in the enemy's country. In the North Sea ports, Calais, Dunkirk, and Ostend, the flotilla numbered four hundred, the troops twenty-seven thousand, the horses twenty-five hundred. These formed the reserve, to follow the main body closely, but apart from it. In the end they also were moved to the Boulogne coast; and their boats, after some sharp fighting with British cruisers, joined the main flotilla in the four Channel ports.

To handle such a mass of men upon the battle-field is a faculty to which few generals, after years of experience, attain. To effect the passage of a broad river with an army of that size, before a watchful enemy of equal force, is a delicate operation. To cross an arm of the sea nearly forty miles wide—for such was the distance separating Boulogne and its sister ports from the intended place of landing, between Dover and Hastings—in the face of a foe whose control of the sea was for the most part undisputed, was an undertaking so bold that men still doubt whether Napoleon meant it; but he assuredly did. For success he looked to the perfect organization and drill of the army and the flotilla, which by practice in embarking and moving should be able to seize, without an hour's delay, the favorable moment he hoped to provide by the great naval combination concealed in his brain. This combination, modified and expanded as the months rolled by, but remaining essentially the same, was the germ whence sprang the intricate and stirring events recorded in this and the following chapters,—events obscured to most men by the dazzling lustre of Trafalgar.

[Between the penning and the publishing of this very positive assertion of the author's convictions, he has met renewed expressions of doubts as to Napoleon's purpose, based upon his words to Metternich in 1810, 98 as well as upon the opinions of persons more or less closely connected with the emperor. As regards the incident recorded by Metternich—it is not merely an easy way of overcoming a difficulty, but the statement of a simple fact, to say that no reliance can be placed upon any avowal of Napoleon's as to his intentions, unless corroborated by circumstances. That the position at Boulogne was well chosen for turning his arms against Austria at a moment's notice, is very true; but it is likewise true that, barring the power of the British navy, it was equally favorable to an invasion of England. What then does this amount to, but that the great captain, as always in his career, met a strategic exigency arising from the existence of two dangers in divergent directions, by taking a central position, whence he could readily turn his arms against either before the other came up?

The considerations that to the author possess irresistible force are: (1) that Napoleon actually did undertake the almost equally hazardous expedition to Egypt; (2) that he saw, with his clear intuition, that, if he did not accept the risk of being destroyed with his army in crossing the Channel, Great Britain would in the end overwhelm him by her sea power, and that therefore, extreme as was the danger of destruction in one case, it was less than in the other alternative,—an argument further developed in the later portions of this work. (3) Inscrutable as are the real purposes of so subtle a spirit, the author holds with Thiers and Lanfrey, that it is impossible to rise from the perusal of Napoleon's correspondence during these thirty months, without the conviction that so sustained a deception as it would contain—on the supposition that the invasion was not intended—would be impossible even to him. It may also be remarked that the Memoirs of Marmont and Ney, who commanded corps in the Army of Invasion, betray no doubt of a purpose which the first explicitly asserts; nor does the life of Marshal Davout, another corps commander, record any such impression on his part. 99]

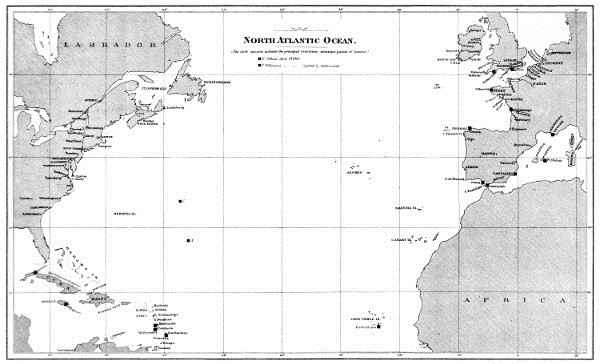

North Atlantic Ocean.

Meanwhile that period of waiting from May, 1803, to August, 1805, when the tangled net of naval and military movements began to unravel, was a striking and wonderful pause in the world's history. On the heights above Boulogne, and along the narrow strip of beach from Étaples to Vimereux, were encamped one hundred and thirty thousand of the most brilliant soldiery of all time, the soldiers who had fought in Germany, Italy, and Egypt, soldiers who were yet to win, from Austria, Ulm and Austerlitz, and from Prussia, Auerstadt and Jena, to hold their own, though barely, at Eylau against the army of Russia, and to overthrow it also, a few months later, on the bloody field of Friedland. Growing daily more vigorous in the bracing sea air and the hardy life laid out for them, they could on fine days, as they practised the varied manœuvres which were to perfect the vast host in embarking and disembarking with order and rapidity, see the white cliffs fringing the only country that to the last defied their arms. Far away, Cornwallis off Brest, Collingwood off Rochefort, Pellew off Ferrol, were battling the wild gales of the Bay of Biscay, in that tremendous and sustained vigilance which reached its utmost tension in the years preceding Trafalgar, concerning which Collingwood wrote that admirals need to be made of iron, but which was forced upon them by the unquestionable and imminent danger of the country. Farther distant still, severed apparently from all connection with the busy scene at Boulogne, Nelson before Toulon was wearing away the last two years of his glorious but suffering life, fighting the fierce north-westers of the Gulf of Lyon and questioning, questioning continually with feverish anxiety, whether Napoleon's object was Egypt again or Great Britain really. They were dull, weary, eventless months, those months of watching and waiting of the big ships before the French arsenals. Purposeless they surely seemed to many, but they saved England. The world has never seen a more impressive demonstration of the influence of sea power upon its history. Those far distant, storm-beaten ships, upon which the Grand Army never looked, stood between it and the dominion of the world. Holding the interior positions they did, before—and therefore between—the chief dockyards and detachments of the French navy, the latter could unite only by a concurrence of successful evasions, of which the failure of any one nullified the result. Linked together as the various British fleets were by chains of smaller vessels, chance alone could secure Bonaparte's great combination, which depended upon the covert concentration of several detachments upon a point practically within the enemy's lines. Thus, while bodily present before Brest, Rochefort, and Toulon, strategically the British squadrons lay in the Straits of Dover barring the way against the Army of Invasion.

The Straits themselves, of course, were not without their own special protection. Both they and their approaches, in the broadest sense of the term, from the Texel to the Channel Islands, were patrolled by numerous frigates and smaller vessels, from one hundred to a hundred and fifty in all. These not only watched diligently all that happened in the hostile harbors and sought to impede the movements of the flat-boats, but also kept touch with and maintained communication between the detachments of ships-of-the-line. Of the latter, five off the Texel watched the Dutch navy, while others were anchored off points of the English coast with reference to probable movements of the enemy. Lord St. Vincent, whose ideas on naval strategy were clear and sound, though he did not use the technical terms of the art, discerned and provided against the very purpose entertained by Bonaparte, of a concentration before Boulogne by ships drawn from the Atlantic and Mediterranean. The best security, the most advantageous strategic positions, were doubtless those before the enemy's ports; and never in the history of blockades has there been excelled, if ever equalled, the close locking of Brest by Admiral Cornwallis, both winter and summer, between the outbreak of war and the battle of Trafalgar. It excited not only the admiration but the wonder of contemporaries. 100 In case, however, the French at Brest got out, so the prime minister of the day informed the speaker of the House, Cornwallis's rendezvous was off the Lizard (due north of Brest), so as to go for Ireland, or follow the French up Channel, if they took either direction. Should the French run for the Downs, the five sail-of-the-line at Spithead would also follow them; and Lord Keith (in the Downs) would in addition to his six, and six block ships, have also the North Sea fleet at his command. 101 Thus provision was made, in case of danger, for the outlying detachments to fall back on the strategic centre, gradually accumulating strength, till they formed a body of from twenty-five to thirty heavy and disciplined ships-of-the-line, sufficient to meet all probable contingencies.

Hence, neither the Admiralty nor British naval officers in general shared the fears of the country concerning the peril from the flotilla. "Our first defence," wrote Nelson in 1801, "is close to the enemy's ports; and the Admiralty have taken such precautions, by having such a respectable force under my orders, that I venture to express a well-grounded hope that the enemy would be annihilated before they get ten miles from their own shores." 102 "As to the possibility of the enemy being able in a narrow sea to pass through our blockading and protecting squadron," said Pellew, "with all the secrecy and dexterity and by those hidden means that some worthy people expect, I really, from anything I have seen in the course of my professional experience, am not much disposed to concur in it." 103 Napoleon also understood that his gunboats could not at sea contend against heavy ships with any founded hope of success. "A discussion was started in the camp," says Marmont, "as to the possibility of fighting ships of war with flat boats, armed with 24- and 36-pounders, and as to whether, with a flotilla of several thousands, a squadron might be attacked. It was sought to establish the belief in a possible success; … but, notwithstanding the confidence with which Bonaparte supported this view, he never shared it for a moment." 104 He could not, without belying every military conviction he ever held. Lord St. Vincent therefore steadily refused to countenance the creation of a large force of similar vessels on the plea of meeting them upon their own terms. "Our great reliance," he wrote, "is on the vigilance and activity of our cruisers at sea, any reduction in the number of which, by applying them to guard our ports, inlets, and beaches, would in my judgment tend to our destruction." He knew also that gunboats, if built, could only be manned, as the French flotilla was, by crippling the crews of the cruising ships; for, extensive as were Great Britain's maritime resources, they were taxed beyond their power by the exhausting demands of her navy and merchant shipping.

It is true there existed an enrolled organization called the Sea Fencibles, composed of men whose pursuits were about the water on the coasts and rivers of the United Kingdom; men who in the last war had been exempted from impressment, because of the obligation they took to turn out for the protection of the country when threatened with invasion. When, however, invasion did threaten in 1801, not even the stirring appeals of Nelson, to whom was then entrusted the defence system, could bring them forward; although he assured them their services were absolutely required, at the moment, and on board the coast-defence vessels. Out of a total of 2600 in four districts immediately menaced, only 385 were willing to enter into training or go afloat. The others could not leave their occupations without loss, and prayed that they might be held excused. 105 When the French were actually on the sea, coming, they professed their readiness to fly on board; so, wrote Nelson, we must "trust to our ships being manned at the last moment by this (almost) scrambling manner." In the present war, therefore, St. Vincent resisted the re-establishment of the corps until the impress had manned the ships first commissioned, and even then yielded only to the pressure in the cabinet. "It was an item in the estimates," he said with rough humor, "of no other use than to calm the fears of the old ladies, both in and out." It was upon his former system of close watching the enemy's ports that he relied for the mastery of the Channel, without which Bonaparte's flotilla dared not leave the French coast. "This boat business," as Nelson had said, "may be a part of a great plan of invasion; it can never be the only one." 106 The event did not deceive them.

In one very important particular, however, St. Vincent had seriously imperilled the success of his general policy. Feeling deeply the corruption prevailing in the dockyard and contract systems of that day, as soon as he came to the head of the Admiralty he entered upon a struggle with them, in which he showed both the singleness of purpose and the harshness of his character. Peace, by reducing the dependence of the country upon its naval establishments, favored his designs of reform; and he was consequently unwilling to recognize the signs of renewing strife, or to postpone changes which, however desirable, must inevitably introduce friction and delay under the press of war. Hence, in the second year of this war, Great Britain had in commission ten fewer line-of-battle-ships than at the same period of the former. "Many old and useful officers and a vast number of artificers had been discharged from the king's dockyards; the customary supplies of timber and other important articles of naval stores had been omitted to be kept up; and some articles, including a large portion of hemp, had actually been sold out of the service. A deficiency of workmen and of materials produced, of course, a suspension in the routine of dockyard business. New ships could not be built; nor could old ones be repaired. Many of the ships in commission, too, having been merely patched up, were scarcely in a state to keep the sea." 107 On this point St. Vincent was vulnerable to the attack made upon his administration by Pitt in March, 1804; but as regarded Pitt's main criticism, the refusal to expend money and seamen upon gunboats, he was entirely right, and his view of the question was that of a statesman and of a man of correct military instincts. 108 Nor, after his experience with the Sea Fencibles, can he be blamed for not sharing Pitt's emotion over "a number of gallant and good old men, coming forward with the zeal and spirit of lads swearing allegiance to the king," &c. 109

These ill-timed changes affected most injuriously that very station—the Mediterranean—upon which hinged Bonaparte's projected combination. Out of the insufficient numbers, the heaviest squadrons and most seaworthy ships were naturally and properly massed upon the Channel and Biscay coasts. "I know," said Sir Edward Pellew, speaking of his personal experience in command of a squadron of six of the line off Ferrol, "I know and can assert with confidence that our navy was never better found, that it was never better supplied and that our men were never better fed or better clothed;" 110 and the condition of the ships was proved not only by the tenacity with which Pellew and his chief, Cornwallis, kept their stations, but by the fact that in the furious winter gales little damage was received. But at the same time Nelson was complaining bitterly that his ships were not seaworthy, that they were shamefully equipped, and destitute of the most necessary stores; while St. Vincent was writing to him, "We can send you neither ships nor men, and with the resources of your mind, you will do without them very well." 111 "Bravo, my lord!" said Nelson, ironically; "but," he wrote a month later, "I do not believe Lord St. Vincent would have kept the sea with such ships;" 112 and again, naming seven out of the ten under his command, "These are certainly among the very finest ships in our service, the best commanded and the very best manned, yet I wish them safe in England and that I had ships not half so well manned in their room; for it is not a store-ship a week that would keep them in repair." 113