полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, Vol II

Guérin claims great carefulness, but the author owns to much distrust of his accuracy. It is evident, however, from all the quotations, that Fox's statement, May 24, 1795, that in the second year of the war France had taken 860 ships, was much exaggerated. (Speeches, vol. v. p. 419. Longman's, 1815.)

275

In this period of twenty-two years there were eighteen months of maritime peace.

276

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv.

277

Thus it is told of one of the most active of French privateersmen, sailing out of Dunkirk, that "the trade from London to Berwick, in the smacks, was his favorite object; not only from the value of the cargoes, but because they required few hands to man them, and from their good sailing were almost sure to escape British cruisers and get safely into ports of France or Holland." Between 1793 and 1801 this one man had taken thirty-four prizes. (Nav. Chron., vol. xii. p. 454.)

278

Returns of the coasting trade were not made until 1824. Porter's Progress of the Nation, section iii. p. 77.

279

The merchant vessels of that day were generally small. From Macpherson's tables it appears that those trading between Great Britain and the United States, between 1792 and 1800, averaged from 200 to 230 tons; those to the West Indies and the Baltic about 250; to Germany, to Italy, and the Western Mediterranean, 150; to the Levant, 250 to 300, with some of 500 tons. The East India Company's ships, as has been said, were larger, averaging nearly 800 tons. The general average is reduced to that above given (125) by the large number of vessels in the Irish trade. In 1796 there were 13,558 entries and clearances from English and Scotch ports for Ireland, being more than half the entire number (not tonnage) of British ships employed in so-called foreign trade. The average size of these was only 80 tons. (Macpherson.) In 1806 there were 13,939 for Ireland to 5,211 for all other parts of the world, the average tonnage again being 80. (Porter's Progress of the Nation, part ii. pp. 85, 174.)

Sir William Parker, an active frigate captain, who commanded the same ship from 1801 to 1811, was in that period interested in 52 prizes. The average tonnage of these, excluding a ship-of-the-line and a frigate, was 126 tons. (Life, vol. i. p. 412.)

In 1798, 6,844 coasters entered or left London, their average size being 73 tons. The colliers were larger. Of the latter 3,289 entered or sailed, having a mean tonnage of 228. (Colquhoun's Commerce of the Thames, p. 13.)

280

The returns for 1813 were destroyed by fire, and so an exact aggregate cannot be given. Two million tons are allowed for that year, which is probably too little.

281

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. 368, 535.

282

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. 368, 535.

283

Porter's Progress of the Nation, part ii. p. 171.

284

Porter's Progress of the Nation, part ii. p. 171.

285

Chalmer's Historical View, p. 307.

286

Porter, part ii. p. 173. The Naval Chronicle, vol. xxix. p. 453, gives an official tabular statement of prize-vessels admitted to registry between 1793 and 1812. In 1792 there were but 609, total tonnage 93,994.

287

Chalmer's Historical View, p. 351.

288

The amounts given are those known as the "official values," assigned arbitrarily to the specific articles a century before. The advantage attaching to this system is, that, no fluctuation of price entering as a factor, the values continue to represent from year to year the proportion of trade done. Official values are used throughout this chapter when not otherwise stated. The "real values," deduced from current prices, were generally much greater than the official. Thus, in 1800, the whole volume of trade, by official value £73,723,000, was by real value £111,231,000. The figures are taken from Macpherson's Annals of Commerce.

289

The French will not suffer a Power which seeks to found its prosperity upon the misfortunes of other states, to raise its commerce upon the ruin of that of other states, and which, aspiring to the dominion of the seas, wishes to introduce everywhere the articles of its own manufacture and to receive nothing from foreign industry, any longer to enjoy the fruit of its guilty speculations.—Message of Directory to the Council of Five Hundred, Jan. 4, 1798.

290

Message of Directory to Council of Five Hundred, Jan. 4, 1798.

291

The act imposing these duties went into effect Aug. 15, 1789. Vessels built in the United States, and owned by her citizens, paid an entrance duty of six cents per ton; all other vessels fifty cents. A discount of ten per cent on the established duties was also allowed upon articles imported in vessels built and owned in the country. (Annals of Congress. First Congress, pp. 2131, 2132.)

292

Am. State Papers, vol. x. 502.

293

Ibid., p. 389.

294

Ibid., p. 528.

295

Ibid., p. 584.

296

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. 535.

297

Am. State Papers, vol. i. 243.

298

Annual Register, 1793, p. 346*.

299

Am. State Papers, i. 240. A complete series of the orders injuriously affecting United States commerce, issued by Great Britain and France, from 1791 to 1808, can be found in the Am. State Papers, vol. iii. p. 262.

300

Am. State Papers, i. 240, 241. How probable this result was may be seen from the letters of Gouverneur Morris, Oct. 19, 1793, and March 6, 1794. State Papers, vol. i. pp. 375, 404.

301

Am. State Papers, vol. i. p. 679.

302

Wheaton's International Law, p. 753.

303

Monroe to the British Minister of Foreign Affairs. Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 735.

304

Reply to "War in Disguise, or Frauds of the Neutral Flag," by Gouverneur Morris, New York, 1806, p. 22.

305

Russell's Life of Fox, vol. ii. p. 281.

306

Letter to Danish Minister, March 17, 1807. Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. x. p. 406.

307

A letter from an American consul in the West Indies, dated March 7, 1794, gives 220 as the number. This was, however, only a partial account, the orders having been recently received. (Am. State Papers, i. p. 429.)

308

By the ordinance of Aug. 30, 1784. See Annals of Congress, Jan. 13, 1794, p. 192.

309

The National Convention, immediately after the outbreak of war, on the 17th of February, 1793, gave a great extension to the existing permission of trade between the United States and the French colonies; but this could not affect the essential fact that the trade, under some conditions, had been allowed in peace.

310

In fact Monroe, in another part of the same letter, avows: "The doctrine of Great Britain in every decision is the same.... Every departure from it is claimed as a relaxation of the principle, gratuitously conceded by Great Britain."

311

Mr. Jay seems to have been under some misapprehension in this matter, for upon his return he wrote to the Secretary of State: "The treaty does prohibit re-exportation from the United States of West India commodities in neutral vessels; … but we may carry them direct from French and other West India islands to Europe." (Am. State Papers, i. 520.) This the treaty certainly did not admit.

312

See letter of Thos. Fitzsimmons, Am. State Papers, vol. ii. 347.

313

The pretexts for these seizures seem usually to have been the alleged contraband character of the cargoes.

314

Am. State Papers, vol. ii. 345.

315

It will be remembered that the closing days of May witnessed the culmination of the death struggle between the Jacobins and Girondists, and that the latter finally fell on the second of June.

316

Am. State Papers, vol. i. pp. 284, 286, 748.

317

Ibid., p. 372.

318

One of these complaints was that the United States now prohibited the sale, in her ports, of prizes taken from the British by French cruisers. This practice, not accorded by the treaty with France, and which had made an unfriendly distinction against Great Britain, was forbidden by Jay's treaty.

319

Speech of M. Dentzel in the Conseil des Anciens. Moniteur, An 7, p. 555.

320

Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 28.

321

Ibid., vol. ii. p. 163.

322

Letter to Talleyrand, Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 178.

323

Ibid., vol. i. pp. 740, 748.

324

The day after the news of Rivoli was received, Mr. Pinckney, who had remained in Paris, though unrecognized, was curtly directed to leave France.

325

Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 13.

326

Ibid., p. 14.

327

Ibid., p. 14.

328

American State Papers, vol. ii. p. 14.

329

Moniteur, An v. pp. 164, 167.

330

March 1, and October 8, 1793. Ibid.

331

Speech of Lecouteulx; Moniteur, An v. p. 176.

332

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. 463.

333

Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. 413, note.

334

Of the imports into Germany, three fifths were foreign merchandise re-exported from Great Britain.

335

These figures are all taken from Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv.

336

See Am. State Papers, vol. x. p. 487.

337

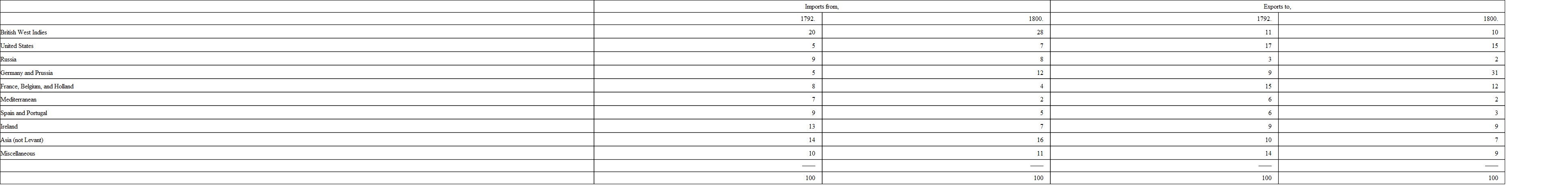

The importance of the West India region to the commercial system of Great Britain in the last decade of the 18th century will be seen from the following table, showing the distribution per cent of British trade in 1792 and 1800:—

The significance of these figures lies not only in the amounts set down directly to the West Indies, but also in the great increase of exports to Germany, and the high rate maintained to France, Belgium, and Holland, with which war existed. Of these exports 25 per cent in 1792, and 43 per cent in 1800, were foreign merchandise, chiefly West Indian—re-exported.

338

In 1800 the captured islands sent 9 per cent of the British imports.

339

Moniteur, An vii. pp 478, 482.

340

Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 8.

341

Moniteur, An vii. p. 502.

342

Ibid., p. 716; Couzard's speech.

343

Moniteur, An vii. p. 555; Dentzel's speech.

344

Ibid.; Lenglet's speech.

345

Ibid., pp. 582, 583. The figures are chiefly taken from the speech of M. Arnould. A person of the same name, who was Chef du Bureau du Commerce, published in 1797 a book called "Système Maritime et Politique des Européens," containing much detailed information about French maritime affairs, and displaying bitter hatred of England. If the deputy himself was not the author, he doubtless had access to the best official intelligence.

346

In consequence of the law of Jan. 18, 1798, the British government appointed a ship-of-the-line and two frigates to convoy a fleet of American vessels to their own coast.—Macpherson's Annals of Commerce, vol. iv. p. 440.

347

Moniteur, An vii. p. 564; Cornet's speech.

348

Annals of Congress, 1798, p. 3733.

349

Ibid., p. 3754.

350

Ibid.

351

Speech of February 2, 1801.

352

Speech of March 25, 1801.

353

Annual Register, 1801; State Papers, p. 212.

354

Ibid., p. 217.

355

The principle of the Rule of 1756, it will be remembered, was that the neutral had no right to carry on, for a belligerent, a trade from which the latter excluded him in peace.

356

By a report submitted to the National Convention, July 3, 1793, it appears that in the years 1787-1789 two tenths only of French commerce was done in French bottoms. In 1792, the last of maritime peace, three tenths was carried by French ships. (Moniteur, 1793, p. 804.)

357

Moniteur, An vii. p. 582; Arnould's speech.

358

Annual Register, 1804. State Papers, p. 286.

359

The exports of the French West India islands in 1788 amounted to $52,000,000, of which $40,000,000 were from San Domingo alone. (Traité d'Économie Politique et de Commerce des Colonies, par P. F. Page. Paris, An 9 (1800) p. 15.) This being for the time almost wholly lost, the effect upon prices can be imagined.

360

An American vessel arrived in Marblehead May 29, landed her cargo on the 30th and 31st, reloaded, and cleared June 3. (Robinson's Admiralty Reports, vol. v. p. 396.)

361

In the case of the brig "Aurora," Mr. Madison, the Secretary of State, wrote: "The duties were paid or secured, according to law, in like manner as they are required to be secured on a like cargo meant for home consumption; when re-shipped, the duties were drawn back with a deduction of three and a half per cent (on them), as is permitted to imported articles in all cases." (Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 732.)

In the case of the American ship "William," captured and sent in, on duties to the amount of $1,239 the drawback was $1,211. (Robinson's Admiralty Reports, vol. v. p. 396.) In the celebrated case of the "Essex," with which began the seizures in 1804, on duties amounting to $5,278, the drawback was $5,080. (Ibid., 405.)

362

The text of the Berlin decree can be found among the series beginning in American State Papers, vol. iii. p. 262.

363

A curious indication of the dependence of the Continent upon British manufactures is afforded by the fact that the French army, during this awful winter, was clad and shod with British goods, imported by the French minister at Hamburg, in face of the Berlin decree. (Bourrienne's Memoirs, vol. vii. p. 292.)

364

Am. State Papers, vol. ii. p. 805.

365

Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. xiii. Appendix, pp. xxxiv-xlv.

366

Thiers, Consulat et Empire, vol. vii. pp. 666-669.

367

Letter of Lord Howick to Mr. Monroe, Jan. 10, 1807; Am. State Papers, vol. iii. p. 5.

368

President's Message to Congress, Oct. 27, 1807; Am. State Papers, vol. iii. p. 5.

369

Correspondance de Napoléon.

370

British Declaration of September 25, 1807,—a paper which ably and completely vindicates the action of Great Britain; Annual Register, 1807, p. 735.

371

Annual Register, 1807. State Papers, p. 771.

372

Ibid., p. 739.

373

Lanfrey's Napoleon (French ed.), vol. iv. p. 153.

374

Corr. de Nap., vol. xv. p. 659.

375

Annual Register, 1807, p. 777.

376

See, for example, Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. viii. pp. 636 and 641-644; vol. ix. p. 87, petition of West India planters; p. 100, speech of Mr. Hibbert, and p. 684, speech of Mr. George Rose.

377

See ante, p. 273.

378

Am. State Papers, vol. iii. pp. 245-247.

379

Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. xiii. Appendix, pp. xxxiv-xlv.

380

Am. State Papers, vol. iii. pp. 23, 24.

381

Annals of Congress, 1807, p. 2814.

382

Annals of Congress, 1808-1809, p. 1824.

383

There were three Orders in Council published on the 11th of November, all relating to the same general subject. They were followed by three others, issued November 25, further explaining or modifying the former three. The author, in his analysis, has omitted reference to particular ones; and has tried to present simply the essential features of the whole, suppressing details.

384

The attention paid to sustaining the commerce of Great Britain was shown most clearly in the second Order of November 11, which overrode the Navigation Act by permitting any friendly vessel to import articles the produce of hostile countries; a permission extended later (by Act of Parliament, April 14, 1808) to any ship, "belonging to any country, whether in amity with his Majesty or not." Enemy's merchant ships were thus accepted as carriers for British trade with restricted ports. See Am. State Papers, vol. iii. pp. 270, 282.

385

Gibraltar and Malta are especially named, they being natural depots for the Mediterranean, whence a large contraband trade was busied in evading Napoleon's measures. The governors of those places were authorized to license even enemy's vessels, if unarmed and not over one hundred tons burthen, to carry on British trade, contrary to the emperor's decrees.

386

On March 28, 1808, an Act of Parliament was passed, fixing the duties on exportations from Great Britain in furtherance of the provisions of the Orders. This Act contained a clause excepting American ships, ordered into British ports, from the tonnage duties laid on those which entered voluntarily.

387

In a debate on the Orders, March 3, 1812, the words of Spencer Perceval, one among the ministers chiefly responsible for them, are thus reported: "With respect to the principle upon which the Orders in Council were founded, he begged to state that he had always considered them as strictly retaliatory; and as far as he could understand the matter they were most completely justified upon the principle of retaliation.... The object of the government was to protect and force the trade of this country, which had been assailed in such an unprecedented manner by the French decrees. If the Orders in Council had not been issued, France would have had free colonial trade by means of neutrals, and we should have been shut out from the Continent.... The object of the Orders in Council was, not to destroy the trade of the Continent, but to force the Continent to trade with us." (Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. xxi. p. 1152.)

As regards the retaliatory effect upon France, Perceval stated that the revenue from customs in France fell from sixty million francs, in 1807, to eighteen and a half million in 1808, and eleven and a half in 1809. (Ibid. p. 1157.)

388

Correspondance de Napoléon, vol. xvii. p. 19.

389

Mr. Henry Adams (History of the United States, 1801-1817) gives 134 as the number of American ships seized between April, 1809, and April, 1810, and estimates the value of the vessels and cargoes at $10,000,000 (Vol. v. p. 242.) The author takes this opportunity of acknowledging his great indebtedness to Mr. Adams's able and exhaustive work, in threading the diplomatic intricacies of this time.

390

December 26, 1805.

391

Metternich's Memoirs, vol. i. p. 82.

392

Metternich to Stadion, Jan. 11, 1809; Memoirs, vol. ii. p. 312.

393

Letter of Napoleon to Louis, dated Trianon, Dec. 20, 1808; Mémoires de Bourrienne, vol. viii. p. 134. Garnier's Louis Bonaparte, p. 351. The date should be 1809. On Dec. 20, 1808, Napoleon was at Madrid, in 1809 at Trianon; not to speak of the allusion to the Austrian war of 1809.

394

Napoleon issued orders to this effect in August, 1807. Cargoes of goods such as England might furnish were sequestrated; those that could not possibly be of British origin, as naval stores and French wines, were admitted. All vessels were to be prevented from leaving the Weser. No notification of this action was given to foreign agents. See Cobbett's Political Register, 1807, pp. 857-859.

395

Thiers, Consulate and Empire (Forbes's translation), vol. xii. p. 21.

396

Mémoires de Bourrienne, French Minister at Hamburg, vol. viii. pp. 193-198.

397

Annual Register, 1809; State Papers, 747.

398

April 1, 1808; Naval Chronicle, vol. xxi. p. 48. May 7, 1809; Annual Register, 1809, p. 698.

399

Napoleon saw, in 1809, that his work at Tilsit was all to be done over, since the only war Russia could make against the English was by commerce, which was protected nearly as before. There was sold in Mayence sugar and coffee which came from Riga.—Mémoires de Savary, duc de Rovigo (Imperial Chief of Police), vol. iii. p. 135.

400

D'Ivernois, Effects of the Continental blockade, London, Jan., 1810. Lord Grenville, one of the leaders of the Opposition, expressed a similar confidence when speaking in the House of Lords, Feb. 8, 1810. (Cobbett's Parl. Debates, vol. xv. p. 347.) So also the King's speech at the opening of Parliament, Jan. 19, 1809: "The public revenues, notwithstanding we are shut out from almost all the continent of Europe and entirely from the United States, has increased to a degree never expected, even by those persons who were most sanguine." (Naval Chronicle, vol. xxi. p. 48.)

401

Monthly Magazine, vol. xxi. p. 195.

402

Ibid., vol. xxii. p. 514.

403

Ibid., vol. xxi. p. 539.

404

Monthly Magazine, vol. xxii. p. 618.

405

Ibid., vol. xxiv. p. 611.

406

Ibid., vol. xxvi. p. 11.

407

Ibid., vol. xxvii. pp. 417, 641.