полная версия

полная версияThe Influence of Sea Power upon the French Revolution and Empire 1793-1812, Vol II

Thus ended, and forever, Napoleon's profoundly conceived and laboriously prepared scheme for the invasion of England. If it be sought to fix a definite moment which marked the final failure of so vast a plan, that one may well be chosen when Villeneuve made signal to bear up for Cadiz. When, precisely, Napoleon learned the truth, does not appear. Decrès, the Minister of Marine, had however prepared him in some measure for Villeneuve's action; and, after a momentary outburst of rage against the unfortunate admiral, he at once issued in rapid succession the directions, by which, to use his own graphic expression, his legions were made to "pirouette," and the march toward the Rhine and Upper Danube was begun. "My decision is taken," he writes to Talleyrand, August 25; "my movement is begun. Three weeks hence I shall be in Germany with two hundred thousand men." During that and the two following days order after order issued from his headquarters; and on the 28th he wrote to Duroc that the army was in full movement. To conceal his change of purpose and to gain all-important time, by lulling the suspicions of Austria, he himself remained at Boulogne, with his eyes seemingly fixed seaward, until the 3d of September, when he went to Paris. On the 24th he left the capital for the army, on the 26th he was at Strasbourg, and on the 7th of October the French army, numbering near two hundred thousand, struck the Danube below Ulm; cutting off some eighty thousand Austrians there assembled under General Mack. On the 20th, the day before Trafalgar, Ulm capitulated; thirty thousand men laying down their arms. Thirty thousand more had been taken in the actions preceding this event. 240 On the 13th of November French troops entered Vienna, and on the 2d of December the battle of Austerlitz was won over the combined Russians and Austrians. On the 26th the emperor of Germany signed the Peace of Presburg. By it he relinquished Venice with all other possessions in Italy, and ceded the Tyrol to Bavaria, the ally of France.

Austria was thus quieted for three years, but the expedition against Great Britain was never resumed. In the course of the following year difficulties arose between Prussia and France, which led to war and the overthrow of the North German kingdom at Auerstadt and Jena. Yet another campaign was needed to bring Russia to peace in 1807. Meanwhile the Boulogne flotilla was rotting on the beach. In October, 1807, Decrès, by Napoleon's orders, made an inspection of the boats and the four ports. Of the twelve hundred of the former, specially built for the invasion, not over three hundred were fit to put to sea; of the nine hundred transports nearly all were past service. The circular port at Boulogne was covered two feet deep with sand; those of Vimereux and Ambleteuse, three feet. A very few years more would suffice to bury them. 241 In 1814 an English lady, visiting Boulogne after Napoleon's first abdication, noted in her journal that the mud walls of the encampment were still to be seen on the heights behind the town,—the crumbling record of a great failure.

The question will naturally here arise, What at any time were the chances of success? To a purely speculative question, involving so many elements and into which the conditions of sea war then introduced so many varying quantities, it would be folly to reply with a positive assertion. Certain determining factors may, however, be profitably noted. It is, for instance, evident that, if Villeneuve on leaving the West Indies had had with him the Ferrol squadron, and still more if he had been joined by Ganteaume, he could have steered at once for the Channel; and, by attending to well-known weather conditions, could have entered it with a favoring wind sure to last him to Boulogne. The difficulty of effecting such a combination in the West Indies, which was Napoleon's favorite project, was owing to the presence of British divisions before the hostile ports; and step by step this circumstance drove the emperor back on what he pronounced the worst alternative,—a concentration in front of Brest. As has been noticed, at the critical moment when this final concentration was to be attempted, the British, by a series of movements which resulted naturally from their strategic policy, were before that port in force superior to either of the French detachments seeking there to make their junction. Cornwallis's blunder in dividing that force cannot obscure the military lesson involved.

Nor can Calder's error, in suffering Villeneuve to escape him in July, detract from the equally significant and precisely similar lesson then illustrated. There also the British fleet was on hand to check an important junction—at a point so far from Ferrol as to be out of supporting distance by the division in the port—by virtue of an intelligent use of interior positions and interior lines.

To the strategic advantage conferred by these interior positions, for clinging to which credit is due above all to St. Vincent, is to be added the very superior character of the British personnel,—particularly of the officers; for the immense demand for seamen made it hard to maintain the quality of the crews. Continually cruising, not singly but in squadrons more or less numerous, the ships were ever on the drill ground,—nay, on the battle-field,—experiencing all the varying phases impressed upon it by the changes of the ocean. Thus practised and hardened into perfect machines, though inferior in numbers, they were continually superior in force and in mobility to their opponents.

Possessing, therefore, strategic advantage and superior force, the probabilities favored Great Britain. Nevertheless, there remained to Napoleon enough chances of success to forbid saying that his enterprise was hopeless. A seaman can scarcely deny that, despite the genius of Nelson and the tenacity of the British officers, it was possible that some favorable concurrence of circumstances might have brought forty or more French ships into the Channel, and given Napoleon the mastery of the Straits for the few days he asked. The very removal of the squadrons of observation from before Rochefort and Ferrol, in order to constitute the fleet with which Calder fought Villeneuve, though admirable as a display of generalship, shows that the British navy, so far as numbers were concerned, was not adequate to perfect security, and might, by some conceivable combination of circumstances, have been outwitted and overwhelmed at the decisive point.

The importance attached by the emperor to his project was not exaggerated. He might, or he might not, succeed; but, if he failed against Great Britain, he failed everywhere. This he, with the intuition of genius, felt; and to this the record of his after history now bears witness. To the strife of arms with the great Sea Power succeeded the strife of endurance. Amid all the pomp and circumstance of the war which for ten years to come desolated the Continent, amid all the tramping to and fro over Europe of the French armies and their auxiliary legions, there went on unceasingly that noiseless pressure upon the vitals of France, that compulsion, whose silence, when once noted, becomes to the observer the most striking and awful mark of the working of Sea Power. Under it the resources of the Continent wasted more and more with each succeeding year; and Napoleon, amid all the splendor of his imperial position, was ever needy. To this, and to the immense expenditures required to enforce the Continental System, are to be attributed most of those arbitrary acts which made him the hated of the peoples, for whose enfranchisement he did so much. Lack of revenue and lack of credit, such was the price paid by Napoleon for the Continental System, through which alone, after Trafalgar, he hoped to crush the Power of the Sea. It may be doubted whether, amid all his glory, he ever felt secure after the failure of the invasion of England. To borrow his own vigorous words, in the address to the nation issued before he joined the army, "To live without commerce, without shipping, without colonies, subjected to the unjust will of our enemies, is to live as Frenchmen should not." Yet so had France to live throughout his reign, by the will of the one enemy never conquered.

On the 14th of September, before quitting Paris, Napoleon sent Villeneuve orders to take the first favorable opportunity to leave Cadiz, to enter the Mediterranean, join the ships at Cartagena, and with this combined force move upon southern Italy. There, at any suitable point, he was to land the troops embarked in the fleet to re-enforce General St. Cyr, who already had instructions to be ready to attack Naples at a moment's notice. 242 The next day these orders were reiterated to Decrès, enforcing the importance to the general campaign of so powerful a diversion as the presence of this great fleet in the Mediterranean; but, as "Villeneuve's excessive pusillanimity will prevent him from undertaking this, you will send to replace him Admiral Rosily, who will bear letters directing Villeneuve to return to France and give an account of his conduct." 243 The emperor had already formulated his complaints against the admiral under seven distinct heads. 244 On the 15th of September, the same day the orders to relieve Villeneuve were issued, Nelson, having spent at home only twenty-five days, left England for the last time. On the 28th, when he joined the fleet off Cadiz, he found under his command twenty-nine ships-of-the-line, which successive arrivals raised to thirty-three by the day of the battle; but, water running short, it became necessary to send the ships, by divisions of six, to fill up at Gibraltar. To this cause was due that only twenty-seven British vessels were present in the action,—an unfortunate circumstance; for, as Nelson said, what the country wanted was not merely a splendid victory, but annihilation; "numbers only can annihilate." 245 The force under his command was thus disposed: the main body about fifty miles west-south-west of Cadiz, seven lookout frigates close in with the port, and between these extremes, two small detachments of ships-of-the-line,—the one twenty miles from the harbor, the other about thirty-five. "By this chain," he wrote, "I hope to have constant communication with the frigates."

Napoleon's commands to enter the Mediterranean reached Villeneuve on September 27. The following day, when Nelson was joining his fleet, the admiral acknowledged their receipt, and submissively reported his intention to obey as soon as the wind served. Before he could do so, accurate intelligence was received of the strength of Nelson's force, which the emperor had not known. Villeneuve assembled a council of war to consider the situation, and the general opinion was adverse to sailing; but the commander-in-chief, alleging the orders of Napoleon, announced his determination to follow them. To this all submitted. An event, then unforeseen by Villeneuve, precipitated his action.

Admiral Rosily's approach was known in Cadiz some time before he could arrive. It at first made little impression upon Villeneuve, who was not expecting to be superseded. On the 11th of October, however, along with the news that his successor had reached Madrid, there came to him a rumor of the truth. His honor took alarm. If not allowed to remain afloat, how remove the undeserved imputation of cowardice which he knew had by some been attached to his name. He at once wrote to Decrès that he would have been well content if permitted to continue with the fleet in a subordinate capacity; and closed with the words, "I will sail to-morrow, if circumstances favor."

The wind next day was fair, and the combined fleets began to weigh. On the 19th eight ships got clear of the harbor, and by ten A. M. Nelson, far at sea, knew by signal that the long-expected movement had begun. He at once made sail toward the Straits of Gibraltar to bar the entrance of the Mediterranean to the allies. On the 20th, all the latter, thirty-three ships-of-the-line accompanied by five frigates and two brigs, were at sea, steering with a south-west wind to the northward and westward to gain the offing needed before heading direct for the Straits. That morning Nelson, for whom the wind had been fair, was lying to off Cape Spartel to intercept the enemy; and learning from his frigates that they were north of him, he stood in that direction to meet them.

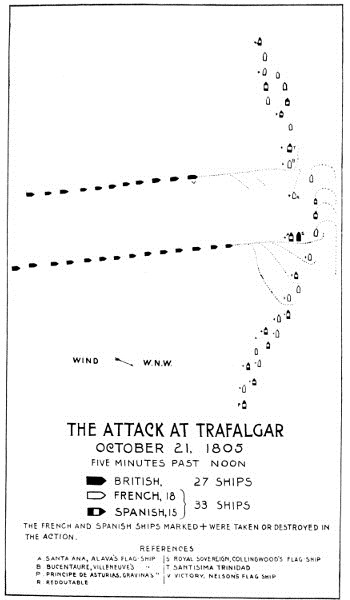

During the day the wind shifted to west, still fair for the British and allowing the allies, by going about, to head south. It was still very weak, so that the progress of the fleets was slow. During the night both manœuvred; the allies to gain, the British to retain, the position they wished. At daybreak of the 21st they were in presence, the French and Spaniards steering south in five columns; of which the two to windward, containing together twelve ships, constituted a detached squadron of observation under Admiral Gravina. The remaining twenty-one formed the main body, commanded by Villeneuve. Cape Trafalgar, from which the battle took its name, was on the south-eastern horizon, ten or twelve miles from the allies; and the British fleet was at the same distance from them to the westward.

Soon after daylight Villeneuve signalled to form line of battle on the starboard tack, on which they were then sailing, heading south. In performing this evolution Gravina with his twelve ships took post in the van of the allied fleet, his own flag-ship heading the column. It is disputed between the French and Spaniards whether this step was taken by Villeneuve's order, or of Gravina's own motion. In either case, these twelve, by abandoning their central and windward position, sacrificed to a great extent their power to re-enforce any threatened part of the order, and also unduly extended a line already too long. In the end, instead of being a reserve well in hand, they became the helpless victims of the British concentration.

At 8 A. M. Villeneuve saw that battle could not be shunned. Wishing to have Cadiz under his lee in case of disaster, he ordered the combined fleet to wear together. The signal was clumsily executed; but by ten all had gone round and were heading north in inverse order, Gravina's squadron in the rear. At eleven Villeneuve directed this squadron to keep well to windward, so as to be in position to succor the centre, upon which the enemy seemed about to make his chief attack; a judicious order, but rendered fruitless by the purpose of the British to concentrate on the rear itself. When this signal was made, Cadiz was twenty miles distant in the north-north-east, and the course of the allies was carrying them toward it.

Owing to the lightness of the wind Nelson would lose no time in manœuvring. He formed his fleet rapidly in two divisions, each in single column, the simplest and most flexible order of attack, and the one whose regularity is most easily preserved. The simple column, however, unflanked, sacrifices during the critical period of closing the support given by the rear ships to the leader, and draws upon the latter the concentrated fire of the enemy's line. Its use by Nelson on this occasion has been much criticised. It is therefore to be remarked that, although his orders, issued several days previous to the battle, are somewhat ambiguous on this point, their natural meaning seems to indicate the intention, if attacking from to windward, to draw up with his fleet in two columns parallel to the enemy and abreast his rear. Then the column nearest the enemy, the lee, keeping away together, would advance in line against the twelve rear ships; while the weather column, moving forward, would hold in check the remainder of the hostile fleet. In either event, whether attacking in column or in line, the essential feature of his plan was to overpower twelve of the enemy by sixteen British, while the remainder of his force covered this operation. The destruction of the rear was entrusted to the second in command; he himself with a smaller body took charge of the more uncertain duties of the containing force. "The second in command," wrote he in his memorable order, "will, after my instructions are made known to him, have the entire direction of his line."

The justification of Nelson's dispositions for battle at Trafalgar rests therefore primarily upon the sluggish breeze, which would so have delayed formations as to risk the loss of the opportunity. It must also be observed that, although a column of ships does not possess the sustained momentum of a column of men, whose depth and mass combine to drive it through the relatively thin resistance of a line, and so cut the latter in twain, the results nevertheless are closely analogous. The leaders in either case are sacrificed,—success is won over their prostrate forms; but the continued impact upon one part of the enemy's order is essentially a concentration, the issue of which, if long enough maintained, cannot be doubtful. Penetration, severance, and the enveloping of one of the parted fragments, must be the result. So, exactly, it was at Trafalgar. It must also be noted that the rear ships of either column, until they reached the hostile line, swept with their broadsides the sea over which enemy's ships from either flank might try to come to the support of the attacked centre. No such attempt was in fact made from either extremity of the combined fleet.

The Attack at Trafalgar.

The two British columns were nearly a mile apart and advanced on parallel courses,—heading nearly east, but a little to the northward to allow for the gradual advance in that direction of the hostile fleet. The northern or left-hand column, commonly called the "weather line" because the wind came rather from that side, contained twelve ships, and was led by Nelson himself in the "Victory," a ship of one hundred guns. The "Royal Sovereign," of the same size and carrying Collingwood's flag, headed the right column, of fifteen ships.

To the British advance the allies opposed the traditional order of battle, a long single line, closehauled,—in this case heading north, with the wind from west-north-west. The distance from one flank to the other was nearly five miles. Owing partly to the lightness of the breeze, partly to the great number of ships, and partly to the inefficiency of many of the units of the fleet, the line was very imperfectly formed. Ships were not in their places, intervals were of irregular width, here vessels were not closed up, there two overlapped, one masking the other's fire. The general result was that, instead of a line, the allied order showed a curve of gradual sweep, convex toward the east. To the British approach from the west, therefore, it presented a disposition resembling a re-entrant angle; and Collingwood, noting with observant eye the advantage of this arrangement for a cross-fire, commented favorably upon it in his report of the battle. It was, however, the result of chance, not of intention,—due, not to the talent of the chief, but to the want of skill in his subordinates.

The commander-in-chief of the allies, Villeneuve, was in the "Bucentaure," an eighty-gun ship, the twelfth in order from the van of the line. Immediately ahead of him was the huge Spanish four-decker, the "Santisima Trinidad," a Goliath among ships, which had now come forth to her last battle. Sixth behind the "Bucentaure," and therefore eighteenth in the order, came a Spanish three-decker, the "Santa Ana," flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Alava. These two admirals marked the right and left of the allied centre, and upon them, therefore, the British leaders respectively directed their course,—Nelson upon the "Bucentaure," Collingwood upon the "Santa Ana."

The "Royal Sovereign" had recently been refitted, and with clean new copper easily outsailed her more worn followers. Thus it happened that, as Collingwood came within range, his ship, outstripping the others by three quarters of a mile, entered alone, and for twenty minutes endured, unsupported, the fire of all the hostile ships that could reach her. A proud deed, surely, but surely also not a deed to be commended as a pattern. The first shot of the battle was fired at her by the "Fougueux," the next astern of the "Santa Ana." This was just at noon, and with the opening guns the ships of both fleets hoisted their ensigns; the Spaniards also hanging large wooden crosses from their spanker booms.

The "Royal Sovereign" advanced in silence until, ten minutes later, she passed close under the stern of the "Santa Ana." Then she fired a double-shotted broadside which struck down four hundred of the enemy's crew, and, luffing rapidly, took her position close alongside, the muzzles of the hostile guns nearly touching. Here the "Royal Sovereign" underwent the fire not only of her chief antagonist, but of four other ships; three of which belonged to the division of five that ought closely to have knit the "Santa Ana" to the "Bucentaure," and so fixed an impassable barrier to the enemy seeking to pierce the centre. The fact shows strikingly the looseness of the allied order, these three being all in rear and to leeward of their proper stations.

For fifteen minutes the "Royal Sovereign" was the only British ship in close action. Then her next astern entered the battle, followed successively by the rest of the column. In rear of the "Santa Ana" were fifteen ships. Among these, Collingwood's vessels penetrated in various directions; chiefly, however, at first near the spot where his flag had led the way, enveloping and destroying in detail the enemy's centre and leading rear ships, and then passing on to subdue the rest. Much doubtless was determined by chance in such confusion and obscurity; but the original tactical plan insured an overwhelming concentration upon a limited portion of the enemy's order. This being subdued with the less loss, because so outnumbered, the intelligence and skill of the various British captains readily compassed the destruction of the dwindling remnant. Of the sixteen ships, including the "Santa Ana," which composed the allied rear, twelve were taken or destroyed.

Not till one o'clock, or nearly half an hour after the vessels next following Collingwood came into action, did the "Victory" reach the "Bucentaure." The latter was raked with the same dire results that befell the "Santa Ana;" but a ship close to leeward blocked the way, and Nelson was not able to grapple with the enemy's commander-in-chief. The "Victory," prevented from going through the line, fell on board the "Redoutable," a French seventy-four, between which and herself a furious action followed,—the two lying in close contact. At half-past one Nelson fell mortally wounded, the battle still raging fiercely.

The ship immediately following Nelson's came also into collision with the "Redoutable," which thus found herself in combat with two antagonists. The next three of the British weather column each in succession raked the "Bucentaure," complying thus with Nelson's order that every effort must be made to capture the enemy's commander-in-chief. Passing on, these three concentrated their efforts, first, upon the "Bucentaure," and next upon the "Santisima Trinidad." Thus it happened that upon the allied commander-in-chief, upon his next ahead, and upon the ship which, though not his natural supporter astern, had sought and filled that honorable post,—upon the key, in short, of the allied order,—were combined under the most advantageous conditions the fires of five hostile vessels, three of them first-rates. Consequently, not only were the three added to the prizes, but also a great breach was made between the van and rear of the combined fleets. This breach became yet wider by the singular conduct of Villeneuve's proper next astern. Soon after the "Victory" came into action, that ship bore up out of the line, wore round, and stood toward the rear, followed by three others. This movement is attributed to a wish to succor the rear. If so, it was at best an indiscreet and ill-timed act, which finds little palliation in the fact that not one of these ships was taken.

Thus, two hours after the battle began, the allied fleet was cut in two, the rear enveloped and in process of being destroyed in detail, the "Bucentaure," "Santisima Trinidad," and "Redoutable" practically reduced, though not yet surrendered. Ahead of the "Santisima Trinidad" were ten ships, which as yet had not been engaged. The inaction of the van, though partly accounted for by the slackness of the wind, has given just cause for censure. To it, at ten minutes before two, Villeneuve made signal to get into action and to wear together. This was accomplished with difficulty, owing to the heavy swell and want of wind. At three, however, all the ships were about, but by an extraordinary fatality they did not keep together. Five with Admiral Dumanoir stood along to windward of the battle, three passed to leeward of it, and two, keeping away, left the field entirely. Of the whole number, three were intercepted, raising the loss of the allies to eighteen ships-of-the-line taken, one of which caught fire and was burned. The approach of Admiral Dumanoir, if made an hour earlier, might have conduced to save Villeneuve; it was now too late. Exchanging a few distant broadsides with enemy's ships, he stood off to the south-west with four vessels; one of those at first with him having been cut off.