полная версия

полная версияProserpina, Volume 1

8. I return to our present special question, then, What is a poppy? and return also to a book I gave away long ago, and have just begged back again, Dr. Lindley's 'Ladies' Botany.' For without at all looking upon ladies as inferior beings, I dimly hope that what Dr. Lindley considers likely to be intelligible to them, may be also clear to their very humble servant.

The poppies, I find, (page 19, vol. i.) differ from crowfeet in being of a stupifying instead of a burning nature, and in generally having two sepals and twice two petals; "but as some poppies have three sepals, and twice three petals, the number of these parts is not sufficiently constant to form an essential mark." Yes, I know that, for I found a superb six-petaled poppy, spotted like a cistus, the other day in a friend's garden. But then, what makes it a poppy still? That it is of a stupifying nature, and itself so stupid that it does not know how many petals it should have, is surely not enough distinction?

9. Returning to Lindley, and working the matter farther out with his help, I think this definition might stand. "A poppy is a flower which has either four or six petals, and two or more treasuries, united into one; containing a milky, stupifying fluid in its stalks and leaves, and always throwing away its calyx when it blossoms."

And indeed, every flower which unites all these characters, we shall, in the Oxford schools, call 'poppy,' and 'Papaver;' but when I get fairly into work, I hope to fix my definitions into more strict terms. For I wish all my pupils to form the habit of asking, of every plant, these following four questions, in order, corresponding to the subject of these opening chapters, namely, "What root has it? what leaf? what flower? and what stem?" And, in this definition of poppies, nothing whatever is said about the root; and not only I don't know myself what a poppy root is like, but in all Sowerby's poppy section, I find no word whatever about that matter.

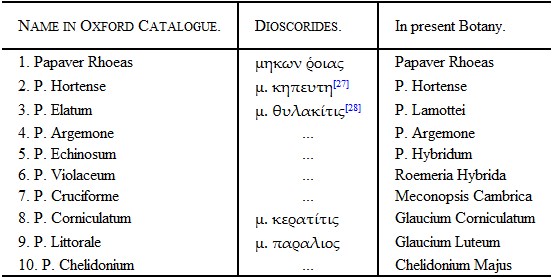

10. Leaving, however, for the present, the root unthought of, and contenting myself with Dr. Lindley's characteristics, I shall place, at the head of the whole group, our common European wild poppy, Papaver Rhoeas, and, with this, arrange the nine following other flowers thus,—opposite.

I must be content at present with determining the Latin names for the Oxford schools; the English ones I shall give as they chance to occur to me, in Gerarde and the classical poets who wrote before the English revolution. When no satisfactory name is to be found, I must try to invent one; as, for instance, just now, I don't like Gerarde's 'Corn-rose' for Papaver Rhoeas, and must coin another; but this can't be done by thinking; it will come into my head some day, by chance. I might try at it straightforwardly for a week together, and not do it.

27 ἧς τὸ σπέρμα ἀρτοποιεῖται.

28 ἐπίμηκες ἔχουσα τὸ κεφάλιον. Dioscorides makes no effort to distinguish species, but gives the different names as if merely used in different places.

The Latin names must be fixed at once, somehow; and therefore I do the best I can, keeping as much respect for the old nomenclature as possible, though this involves the illogical practice of giving the epithet sometimes from the flower, (violaceum, cruciforme), and sometimes from the seed vessel, (elatum, echinosum, corniculatum). Guarding this distinction, however, we may perhaps be content to call the six last of the group, in English, Urchin Poppy, Violet Poppy, Crosslet Poppy, Horned Poppy, Beach Poppy, and Welcome Poppy. I don't think the last flower pretty enough to be connected more directly with the swallow, in its English name.

11. I shall be well content if my pupils know these ten poppies rightly; all of them at present wild in our own country, and, I believe, also European in range: the head and type of all being the common wild poppy of our cornfields for which the name 'Papaver Rhoeas,' given it by Dioscorides, Gerarde, and Linnæus, is entirely authoritative, and we will therefore at once examine the meaning, and reason, of that name.

12. Dioscorides says the name belongs to it "διὰ τὸ ταχέως τὸ ἄνθος ἀποβάλλειν," "because it casts off its bloom quickly," from ῥέω, (rheo) in the sense of shedding.27 And this indeed it does,—first calyx, then corolla;—you may translate it 'swiftly ruinous' poppy, but notice, in connection with this idea, how it droops its head before blooming; an action which, I doubt not, mingled in Homer's thought with the image of its depression when filled by rain, in the passage of the Iliad, which, as I have relieved your memory of three unnecessary names of poppy families, you have memory to spare for learning.

"μήκων δ' ὣς ἑτέρωσε κάρη βάλεν, ἣτ' ἐνὶ κήπῳκαρπῷ βριθομένη, νοτιῇσι τε εἰάρινῇσινὣς ἑτέρωσ' ἤμυσε κάρη πήληκι βαρυνθέν.""And as a poppy lets its head fall aside, which in a garden is loaded with its fruit, and with the soft rains of spring, so the youth drooped his head on one side; burdened with the helmet."

And now you shall compare the translations of this passage, with its context, by Chapman and Pope—(or the school of Pope), the one being by a man of pure English temper, and able therefore to understand pure Greek temper; the other infected with all the faults of the falsely classical school of the Renaissance.

First I take Chapman:—

"His shaft smit fair Gorgythion of Priam's princely raceWho in Æpina was brought forth, a famous town in Thrace,By Castianeira, that for form was like celestial breed.And as a crimson poppy-flower, surcharged with his seed,And vernal humours falling thick, declines his heavy brow,So, a-oneside, his helmet's weight his fainting head did bow."Next, Pope:—

"He missed the mark; but pierced Gorgythio's heart,And drenched in royal blood the thirsty dart:(Fair Castianeira, nymph of form divine,This offspring added to King Priam's line).As full-blown poppies, overcharged with rain,Decline the head, and drooping kiss the plain,So sinks the youth: his beauteous head, depressedBeneath his helmet, drops upon his breast."13. I give you the two passages in full, trusting that you may so feel the becomingness of the one, and the gracelessness of the other. But note farther, in the Homeric passage, one subtlety which cannot enough be marked even in Chapman's English, that his second word, ἤμυσε, is employed by him both of the stooping of ears of corn, under wind, and of Troy stooping to its ruin;28 and otherwise, in good Greek writers, the word is marked as having such specific sense of men's drooping under weight; or towards death, under the burden of fortune which they have no more strength to sustain;29 compare the passage I quoted from Plato, ('Crown of Wild Olive,' p. 95): "And bore lightly the burden of gold and of possessions." And thus you will begin to understand how the poppy became in the heathen mind the type at once of power, or pride, and of its loss; and therefore, both why Virgil represents the white nymph Nais, "pallentes violas, et summa papavera carpens,"—gathering the pale flags, and the highest poppies,—and the reason for the choice of this rather than any other flower, in the story of Tarquin's message to his son.

14. But you are next to remember the word Rhoeas in another sense. Whether originally intended or afterwards caught at, the resemblance of the word to 'Rhoea,' a pomegranate, mentally connects itself with the resemblance of the poppy head to the pomegranate fruit.

And if I allow this flower to be the first we take up for careful study in Proserpina, on account of its simplicity of form and splendour of colour, I wish you also to remember, in connection with it, the cause of Proserpine's eternal captivity—her having tasted a pomegranate seed,—the pomegranate being in Greek mythology what the apple is in the Mosaic legend; and, in the whole worship of Demeter, associated with the poppy by a multitude of ideas which are not definitely expressed, but can only be gathered out of Greek art and literature, as we learn their symbolism. The chief character on which these thoughts are founded is the fulness of seed in the poppy and pomegranate, as an image of life: then the forms of both became adopted for beads or bosses in ornamental art; the pomegranate remains more distinctly a Jewish and Christian type, from its use in the border of Aaron's robe, down to the fruit in the hand of Angelico's and Botticelli's Infant Christs; while the poppy is gradually confused by the Byzantine Greeks with grapes; and both of these with palm fruit. The palm, in the shorthand of their art, gradually becomes a symmetrical branched ornament with two pendent bosses; this is again confused with the Greek iris, (Homer's blue iris, and Pindar's water-flag,)—and the Florentines, in adopting Byzantine ornament, read it into their own Fleur-de-lys; but insert two poppyheads on each side of the entire foil, in their finest heraldry.

15. Meantime the definitely intended poppy, in late Christian Greek art of the twelfth century, modifies the form of the Acanthus leaf with its own, until the northern twelfth century workman takes the thistle-head for the poppy, and the thistle-leaf for acanthus. The true poppy-head remains in the south, but gets more and more confused with grapes, till the Renaissance carvers are content with any kind of boss full of seed, but insist on such boss or bursting globe as some essential part of their ornament;—the bean-pod for the same reason (not without Pythagorean notions, and some of republican election) is used by Brunelleschi for main decoration of the lantern of Florence duomo; and, finally, the ornamentation gets so shapeless, that M. Violet-le-Duc, in his 'Dictionary of Ornament,' loses trace of its origin altogether, and fancies the later forms were derived from the spadix of the arum.

16. I have no time to enter into farther details; but through all this vast range of art, note this singular fact, that the wheat-ear, the vine, the fleur-de-lys, the poppy, and the jagged leaf of the acanthus-weed, or thistle, occupy the entire thoughts of the decorative workmen trained in classic schools, to the exclusion of the rose, true lily, and the other flowers of luxury. And that the deeply underlying reason of this is in the relation of weeds to corn, or of the adverse powers of nature to the beneficent ones, expressed for us readers of the Jewish scriptures, centrally in the verse, "thorns also, and thistles, shall it bring forth to thee; and thou shalt eat the herb of the field" (χορτος, grass or corn), and exquisitely symbolized throughout the fields of Europe by the presence of the purple 'corn-flag,' or gladiolus, and 'corn-rose' (Gerarde's name for Papaver Rhoeas), in the midst of carelessly tended corn; and in the traditions of the art of Europe by the springing of the acanthus round the basket of the canephora, strictly the basket for bread, the idea of bread including all sacred things carried at the feasts of Demeter, Bacchus, and the Queen of the Air. And this springing of the thorny weeds round the basket of reed, distinctly taken up by the Byzantine Italians in the basketwork capital of the twelfth century, (which I have already illustrated at length in the 'Stones of Venice,') becomes the germ of all capitals whatsoever, in the great schools of Gothic, to the end of Gothic time, and also of all the capitals of the pure and noble Renaissance architecture of Angelico and Perugino, and all that was learned from them in the north, while the introduction of the rose, as a primal element of decoration, only takes place when the luxury of English decorated Gothic, the result of that licentious spirit in the lords which brought on the Wars of the Roses, indicates the approach of destruction to the feudal, artistic, and moral power of the northern nations.

For which reason, and many others, I must yet delay the following out of our main subject, till I have answered the other question, which brought me to pause in the middle of this chapter, namely, 'What is a weed?'

CHAPTER VI.

THE PARABLE OF JOASH

1. Some ten or twelve years ago, I bought—three times twelve are thirty-six—of a delightful little book by Mrs. Gatty, called 'Aunt Judy's Tales'—whereof to make presents to my little lady friends. I had, at that happy time, perhaps from four-and-twenty to six-and-thirty—I forget exactly how many—very particular little lady friends; and greatly wished Aunt Judy to be the thirty-seventh,—the kindest, wittiest, prettiest girl one had ever read of, at least in so entirely proper and orthodox literature.

2. Not but that it is a suspicious sign of infirmity of faith in our modern moralists to make their exemplary young people always pretty; and dress them always in the height of the fashion. One may read Miss Edgeworth's 'Harry and Lucy,' 'Frank and Mary,' 'Fashionable Tales,' or 'Parents' Assistant,' through, from end to end, with extremest care; and never find out whether Lucy was tall or short, nor whether Mary was dark or fair, nor how Miss Annaly was dressed, nor—which was my own chief point of interest—what was the colour of Rosamond's eyes. Whereas Aunt Judy, in charming position after position, is shown to have expressed all her pure evangelical principles with the prettiest of lips; and to have had her gown, though puritanically plain, made by one of the best modistes in London.

3. Nevertheless, the book is wholesome and useful; and the nicest story in it, as far as I recollect, is an inquiry into the subject which is our present business, 'What is a weed?'—in which, by many pleasant devices, Aunt Judy leads her little brothers and sisters to discern that a weed is 'a plant in the wrong place.'

'Vegetable' in the wrong place, by the way, I think Aunt Judy says, being a precisely scientific little aunt. But I can't keep it out of my own less scientific head that 'vegetable' means only something going to be boiled. I like 'plant' better for general sense, besides that it's shorter.

Whatever we call them, Aunt Judy is perfectly right about them as far as she has gone; but, as happens often even to the best of evangelical instructresses, she has stopped just short of the gist of the whole matter. It is entirely true that a weed is a plant that has got into a wrong place; but it never seems to have occurred to Aunt Judy that some plants never do!

Who ever saw a wood anemone or a heath blossom in the wrong place? Who ever saw nettle or hemlock in a right one? And yet, the difference between flower and weed, (I use, for convenience sake, these words in their familiar opposition,) certainly does not consist merely in the flowers being innocent, and the weed stinging and venomous. We do not call the nightshade a weed in our hedges, nor the scarlet agaric in our woods. But we do the corncockle in our fields.

4. Had the thoughtful little tutoress gone but one thought farther, and instead of "a vegetable in a wrong place," (which it may happen to the innocentest vegetable sometimes to be, without turning into a weed, therefore,) said, "A vegetable which has an innate disposition to get into the wrong place," she would have greatly furthered the matter for us; but then she perhaps would have felt herself to be uncharitably dividing with vegetables her own little evangelical property of original sin.

5. This, you will find, nevertheless, to be the very essence of weed character—in plants, as in men. If you glance through your botanical books, you will see often added certain names—'a troublesome weed.' It is not its being venomous, or ugly, but its being impertinent—thrusting itself where it has no business, and hinders other people's business—that makes a weed of it. The most accursed of all vegetables, the one that has destroyed for the present even the possibility of European civilization, is only called a weed in the slang of its votaries;30 but in the finest and truest English we call so the plant which has come to us by chance from the same country, the type of mere senseless prolific activity, the American water-plant, choking our streams till the very fish that leap out of them cannot fall back, but die on the clogged surface; and indeed, for this unrestrainable, unconquerable insolence of uselessness, what name can be enough dishonourable?

6. I pass to vegetation of nobler rank.

You remember, I was obliged in the last chapter to leave my poppy, for the present, without an English specific name, because I don't like Gerarde's 'Corn-rose,' and can't yet think of another. Nevertheless, I would have used Gerarde's name, if the corn-rose were as much a rose as the corn-flag is a flag. But it isn't. The rose and lily have quite different relations to the corn. The lily is grass in loveliness, as the corn is grass in use; and both grow together in peace—gladiolus in the wheat, and narcissus in the pasture. But the rose is of another and higher order than the corn, and you never saw a cornfield overrun with sweetbriar or apple-blossom.

They have no mind, they, to get into the wrong place.

What is it, then, this temper in some plants—malicious as it seems—intrusive, at all events, or erring,—which brings them out of their places—thrusts them where they thwart us and offend?

7. Primarily, it is mere hardihood and coarseness of make. A plant that can live anywhere, will often live where it is not wanted. But the delicate and tender ones keep at home. You have no trouble in 'keeping down' the spring gentian. It rejoices in its own Alpine home, and makes the earth as like heaven as it can, but yields as softly as the air, if you want it to give place. Here in England, it will only grow on the loneliest moors, above the high force of Tees; its Latin name, for us (I may as well tell you at once) is to be 'Lucia verna;' and its English one, Lucy of Teesdale.

8. But a plant may be hardy, and coarse of make, and able to live anywhere, and yet be no weed. The coltsfoot, so far as I know, is the first of large-leaved plants to grow afresh on ground that has been disturbed: fall of Alpine débris, ruin of railroad embankment, waste of drifted slime by flood, it seeks to heal and redeem; but it does not offend us in our gardens, nor impoverish us in our fields.

Nevertheless, mere coarseness of structure, indiscriminate hardihood, is at least a point of some unworthiness in a plant. That it should have no choice of home, no love of native land, is ungentle; much more if such discrimination as it has, be immodest, and incline it, seemingly, to open and much-traversed places, where it may be continually seen of strangers. The tormentilla gleams in showers along the mountain turf; her delicate crosslets are separate, though constellate, as the rubied daisy. But the king-cup—(blessing be upon it always no less)—crowds itself sometimes into too burnished flame of inevitable gold. I don't know if there was anything in the darkness of this last spring to make it brighter in resistance; but I never saw any spaces of full warm yellow, in natural colour, so intense as the meadows between Reading and the Thames; nor did I know perfectly what purple and gold meant, till I saw a field of park land embroidered a foot deep with king-cup and clover—while I was correcting my last notes on the spring colours of the Royal Academy—at Aylesbury.

9. And there are two other questions of extreme subtlety connected with this main one. What shall we say of the plants whose entire destiny is parasitic—which are not only sometimes, and impertinently, but always, and pertinently, out of place; not only out of the right place, but out of any place of their own? When is mistletoe, for instance, in the right place, young ladies, think you? On an apple tree, or on a ceiling? When is ivy in the right place?—when wallflower? The ivy has been torn down from the towers of Kenilworth; the weeds from the arches of the Coliseum, and from the steps of the Araceli, irreverently, vilely, and in vain; but how are we to separate the creatures whose office it is to abate the grief of ruin by their gentleness,

"wafting wallflower scentsFrom out the crumbling ruins of fallen pride,And chambers of transgression, now forlorn,"from those which truly resist the toil of men, and conspire against their fame; which are cunning to consume, and prolific to encumber; and of whose perverse and unwelcome sowing we know, and can say assuredly, "An enemy hath done this."

10. Again. The character of strength which gives prevalence over others to any common plant, is more or less consistently dependent on woody fibre in the leaves; giving them strong ribs and great expanding extent; or spinous edges, and wrinkled or gathered extent.

Get clearly into your mind the nature of those two conditions. When a leaf is to be spread wide, like the Burdock, it is supported by a framework of extending ribs like a Gothic roof. The supporting function of these is geometrical; every one is constructed like the girders of a bridge, or beams of a floor, with all manner of science in the distribution of their substance in the section, for narrow and deep strength; and the shafts are mostly hollow. But when the extending space of a leaf is to be enriched with fulness of folds, and become beautiful in wrinkles, this may be done either by pure undulation as of a liquid current along the leaf edge, or by sharp 'drawing'—or 'gathering' I believe ladies would call it—and stitching of the edges together. And this stitching together, if to be done very strongly, is done round a bit of stick, as a sail is reefed round a mast; and this bit of stick needs to be compactly, not geometrically strong; its function is essentially that of starch,—not to hold the leaf up off the ground against gravity; but to stick the edges out, stiffly, in a crimped frill. And in beautiful work of this kind, which we are meant to study, the stays of the leaf—or stay-bones—are finished off very sharply and exquisitely at the points; and indeed so much so, that they prick our fingers when we touch them; for they are not at all meant to be touched, but admired.

11. To be admired,—with qualification, indeed, always, but with extreme respect for their endurance and orderliness. Among flowers that pass away, and leaves that shake as with ague, or shrink like bad cloth,—these, in their sturdy growth and enduring life, we are bound to honour; and, under the green holly, remember how much softer friendship was failing, and how much of other loving, folly. And yet—you are not to confuse the thistle with the cedar that is in Lebanon; nor to forget—if the spinous nature of it become too cruel to provoke and offend—the parable of Joash to Amaziah, and its fulfilment: "There passed by a wild beast that was in Lebanon, and trode down the thistle."

12. Then, lastly, if this rudeness and insensitiveness of nature be gifted with no redeeming beauty; if the boss of the thistle lose its purple, and the star of the Lion's tooth, its light; and, much more, if service be perverted as beauty is lost, and the honied tube, and medicinal leaf, change into mere swollen emptiness, and salt brown membrane, swayed in nerveless languor by the idle sea,—at last the separation between the two natures is as great as between the fruitful earth and fruitless ocean; and between the living hands that tend the Garden of Herbs where Love is, and those unclasped, that toss with tangle and with shells.

13. I had a long bit in my head, that I wanted to write, about St. George of the Seaweed, but I've no time to do it; and those few words of Tennyson's are enough, if one thinks of them: only I see, in correcting press, that I've partly misapplied the idea of 'gathering' in the leaf edge. It would be more accurate to say it was gathered at the central rib; but there is nothing in needlework that will represent the actual excess by lateral growth at the edge, giving three or four inches of edge for one of centre. But the stiffening of the fold by the thorn which holds it out is very like the action of a ship's spars on its sails; and absolutely in many cases like that of the spines in a fish's fin, passing into the various conditions of serpentine and dracontic crest, connected with all the terrors and adversities of nature; not to be dealt with in a chapter on weeds.

14. Here is a sketch of a crested leaf of less adverse temper, which may as well be given, together with Plate III., in this number, these two engravings being meant for examples of two different methods of drawing, both useful according to character of subject. Plate III. is sketched first with a finely-pointed pen, and common ink, on white paper; then washed rapidly with colour, and retouched with the pen to give sharpness and completion. This method is used because the thistle leaves are full of complex and sharp sinuosities, and set with intensely sharp spines passing into hairs, which require many kinds of execution with the fine point to imitate at all. In the drawing there was more look of the bloom or woolliness on the stems, but it was useless to try for this in the mezzotint, and I desired Mr. Allen to leave his work at the stage where it expressed as much form as I wanted. The leaves are of the common marsh thistle, of which more anon; and the two long lateral ones are only two different views of the same leaf, while the central figure is a young leaf just opening. It beat me, in its delicate bossing, and I had to leave it, discontentedly enough.