полная версия

полная версияProserpina, Volume 1

I find an excellent illustration in Veronica Polita, one of the most perfectly graceful of field plants because of the light alternate flower stalks, each with its leaf at the base; the flower itself a quatrefoil, of which the largest and least petals are uppermost. Pull one off its calyx (draw, if you can, the outline of the striped blue upper petal with the jagged edge of pale gold below), and then examine the relative shapes of the lateral, and least upper petal. Their under surface is very curious, as if covered with white paint; the blue stripes above, in the direction of their growth, deepening the more delicate colour with exquisite insistence.

A lilac blossom will give you a pretty example of the expansion of the petals of a quatrefoil above the edge of the cup or tube; but I must get back to our poppy at present.

15. What outline its petals really have, however, is little shown in their crumpled fluttering; but that very crumpling arises from a fine floral character which we do not enough value in them. We usually think of the poppy as a coarse flower; but it is the most transparent and delicate of all the blossoms of the field. The rest—nearly all of them—depend on the texture of their surfaces for colour. But the poppy is painted glass; it never glows so brightly as when the sun shines through it. Wherever it is seen—against the light or with the light—always, it is a flame, and warms the wind like a blown ruby.

In these two qualities, the accurately balanced form, and the perfectly infused colour of the petals, you have, as I said, the central being of the flower. All the other parts of it are necessary, but we must follow them out in order.

16. Looking down into the cup, you see the green boss divided by a black star,—of six rays only,—and surrounded by a few black spots. My rough-nurtured poppy contents itself with these for its centre; a rich one would have had the green boss divided by a dozen of rays, and surrounded by a dark crowd of crested threads.

This green boss is called by botanists the pistil, which word consists of the two first syllables of the Latin pistillum, otherwise more familiarly Englished into 'pestle.' The meaning of the botanical word is of course, also, that the central part of a flower-cup has to it something of the relations that a pestle has to a mortar! Practically, however, as this pestle has no pounding functions, I think the word is misleading as well as ungraceful; and that we may find a better one after looking a little closer into the matter. For this pestle is divided generally into three very distinct parts: there is a storehouse at the bottom of it for the seeds of the plant; above this, a shaft, often of considerable length in deep cups, rising to the level of their upper edge, or above it; and at the top of these shafts an expanded crest. This shaft the botanists call 'style,' from the Greek word for a pillar; and the crest of it—I do not know why—stigma, from the Greek word for 'spot.' The storehouse for the seeds they call the 'ovary,' from the Latin ovum, an egg. So you have two-thirds of a Latin word, (pistil)—awkwardly and disagreeably edged in between pestle and pistol—for the whole thing; you have an English-Latin word (ovary) for the bottom of it; an English-Greek word (style) for the middle; and a pure Greek word (stigma) for the top.

17. This is a great mess of language, and all the worse that the words style and stigma have both of them quite different senses in ordinary and scholarly English from this forced botanical one. And I will venture therefore, for my own pupils, to put the four names altogether into English. Instead of calling the whole thing a pistil, I shall simply call it the pillar. Instead of 'ovary,' I shall say 'Treasury' (for a seed isn't an egg, but it is a treasure). The style I shall call the 'Shaft,' and the stigma the 'Volute.' So you will have your entire pillar divided into the treasury, at its base, the shaft, and the volute; and I think you will find these divisions easily remembered, and not unfitted to the sense of the words in their ordinary use.

18. Round this central, but, in the poppy, very stumpy, pillar, you find a cluster of dark threads, with dusty pendants or cups at their ends. For these the botanists' name 'stamens,' may be conveniently retained, each consisting of a 'filament,' or thread, and an 'anther,' or blossoming part.

And in this rich corolla, and pillar, or pillars, with their treasuries, and surrounding crowd of stamens, the essential flower consists. Fewer than these several parts, it cannot have, to be a flower at all; of these, the corolla leads, and is the object of final purpose. The stamens and the treasuries are only there in order to produce future corollas, though often themselves decorative in the highest degree.

These, I repeat, are all the essential parts of a flower. But it would have been difficult, with any other than the poppy, to have shown you them alone; for nearly all other flowers keep with them, all their lives, their nurse or tutor leaves,—the group which, in stronger and humbler temper, protected them in their first weakness, and formed them to the first laws of their being. But the poppy casts these tutorial leaves away. It is the finished picture of impatient and luxury-loving youth,—at first too severely restrained, then casting all restraint away,—yet retaining to the end of life unseemly and illiberal signs of its once compelled submission to laws which were only pain,—not instruction.

19. Gather a green poppy bud, just when it shows the scarlet line at its side; break it open and unpack the poppy. The whole flower is there complete in size and colour,—its stamens full-grown, but all packed so closely that the fine silk of the petals is crushed into a million of shapeless wrinkles. When the flower opens, it seems a deliverance from torture: the two imprisoning green leaves are shaken to the ground; the aggrieved corolla smooths itself in the sun, and comforts itself as it can; but remains visibly crushed and hurt to the end of its days.

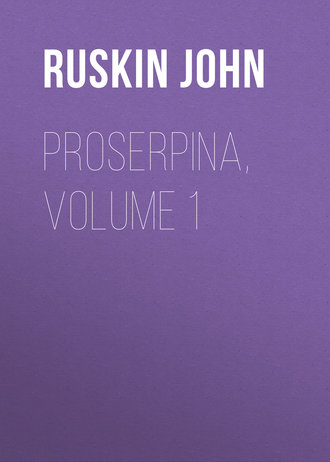

Fig. 7.

20. Not so flowers of gracious breeding. Look at these four stages in the young life of a primrose, Fig. 7. First confined, as strictly as the poppy within five pinching green leaves, whose points close over it, the little thing is content to remain a child, and finds its nursery large enough. The green leaves unclose their points,—the little yellow ones peep out, like ducklings. They find the light delicious, and open wide to it; and grow, and grow, and throw themselves wider at last into their perfect rose. But they never leave their old nursery for all that; it and they live on together; and the nursery seems a part of the flower.

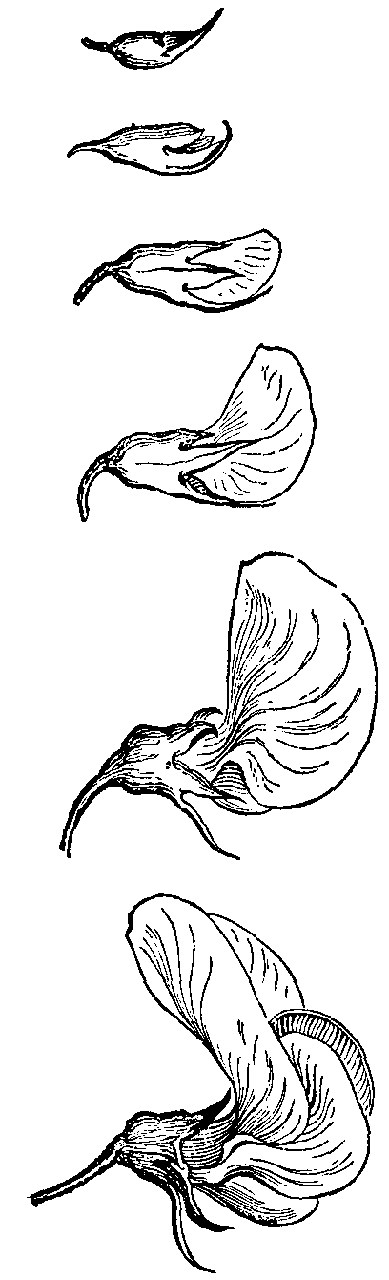

21. Which is so, indeed, in all the loveliest flowers; and, in usual botanical parlance, a flower is said to consist of its calyx, (or hiding part—Calypso having rule over it,) and corolla, or garland part, Proserpina having rule over it. But it is better to think of them always as separate; for this calyx, very justly so named from its main function of concealing the flower, in its youth is usually green, not coloured, and shows its separate nature by pausing, or at least greatly lingering, in its growth, and modifying itself very slightly, while the corolla is forming itself through active change. Look at the two, for instance, through the youth of a pease blossom, Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

The entire cluster at first appears pendent in this manner, the stalk bending round on purpose to put it into that position. On which all the little buds, thinking themselves ill-treated, determine not to submit to anything of the sort, turn their points upward persistently, and determine that—at any cost of trouble—they will get nearer the sun. Then they begin to open, and let out their corollas. I give the process of one only (Fig. 9).24 It chances to be engraved the reverse way from the bud; but that is of no consequence.

Fig. 9.

At first, you see the long lower point of the calyx thought that it was going to be the head of the family, and curls upwards eagerly. Then the little corolla steals out; and soon does away with that impression on the mind of the calyx. The corolla soars up with widening wings, the abashed calyx retreats beneath; and finally the great upper leaf of corolla—not pleased at having its back still turned to the light, and its face down—throws itself entirely back, to look at the sky, and nothing else;—and your blossom is complete.

Keeping, therefore, the ideas of calyx and corolla entirely distinct, this one general point you may note of both: that, as a calyx is originally folded tight over the flower, and has to open deeply to let it out, it is nearly always composed of sharp pointed leaves like the segments of a balloon; while corollas, having to open out as wide as possible to show themselves, are typically like cups or plates, only cut into their edges here and there, for ornamentation's sake.

22. And, finally, though the corolla is essentially the floral group of leaves, and usually receives the glory of colour for itself only, this glory and delight may be given to any other part of the group; and, as if to show us that there is no really dishonoured or degraded membership, the stalks and leaves in some plants, near the blossom, flush in sympathy with it, and become themselves a part of the effectively visible flower;—Eryngo—Jura hyacinth, (comosus,) and the edges of upper stems and leaves in many plants; while others, (Geranium lucidum,) are made to delight us with their leaves rather than their blossoms; only I suppose, in these, the scarlet leaf colour is a kind of early autumnal glow,—a beautiful hectic, and foretaste, in sacred youth, of sacred death.

I observe, among the speculations of modern science, several, lately, not uningenious, and highly industrious, on the subject of the relation of colour in flowers, to insects—to selective development, etc., etc. There are such relations, of course. So also, the blush of a girl, when she first perceives the faltering in her lover's step as he draws near, is related essentially to the existing state of her stomach; and to the state of it through all the years of her previous existence. Nevertheless, neither love, chastity, nor blushing, are merely exponents of digestion.

All these materialisms, in their unclean stupidity, are essentially the work of human bats; men of semi-faculty or semi-education, who are more or less incapable of so much as seeing, much less thinking about, colour; among whom, for one-sided intensity, even Mr. Darwin must be often ranked, as in his vespertilian treatise on the ocelli of the Argus pheasant, which he imagines to be artistically gradated, and perfectly imitative of a ball and socket. If I had him here in Oxford for a week, and could force him to try to copy a feather by Bewick, or to draw for himself a boy's thumbed marble, his notions of feathers, and balls, would be changed for all the rest of his life. But his ignorance of good art is no excuse for the acutely illogical simplicity of the rest of his talk of colour in the "Descent of Man." Peacocks' tails, he thinks, are the result of the admiration of blue tails in the minds of well-bred peahens,—and similarly, mandrills' noses the result of the admiration of blue noses in well-bred baboons. But it never occurs to him to ask why the admiration of blue noses is healthy in baboons, so that it develops their race properly, while similar maidenly admiration either of blue noses or red noses in men would be improper, and develop the race improperly. The word itself 'proper' being one of which he has never asked, or guessed, the meaning. And when he imagined the gradation of the cloudings in feathers to represent successive generation, it never occurred to him to look at the much finer cloudy gradations in the clouds of dawn themselves; and explain the modes of sexual preference and selective development which had brought them to their scarlet glory, before the cock could crow thrice. Putting all these vespertilian speculations out of our way, the human facts concerning colour are briefly these. Wherever men are noble, they love bright colour; and wherever they can live healthily, bright colour is given them—in sky, sea, flowers, and living creatures.

On the other hand, wherever men are ignoble and sensual, they endure without pain, and at last even come to like (especially if artists,) mud-colour and black, and to dislike rose-colour and white. And wherever it is unhealthy for them to live, the poisonousness of the place is marked by some ghastly colour in air, earth, or flowers.

There are, of course, exceptions to all such widely founded laws; there are poisonous berries of scarlet, and pestilent skies that are fair. But, if we once honestly compare a venomous wood-fungus, rotting into black dissolution of dripped slime at its edges, with a spring gentian; or a puff adder with a salmon trout, or a fog in Bermondsey with a clear sky at Berne, we shall get hold of the entire question on its right side; and be able afterwards to study at our leisure, or accept without doubt or trouble, facts of apparently contrary meaning. And the practical lesson which I wish to leave with the reader is, that lovely flowers, and green trees growing in the open air, are the proper guides of men to the places which their Maker intended them to inhabit; while the flowerless and treeless deserts—of reed, or sand, or rock,—are meant to be either heroically invaded and redeemed, or surrendered to the wild creatures which are appointed for them; happy and wonderful in their wild abodes.

Nor is the world so small but that we may yet leave in it also unconquered spaces of beautiful solitude; where the chamois and red deer may wander fearless,—nor any fire of avarice scorch from the Highlands of Alp, or Grampian, the rapture of the heath, and the rose.

CHAPTER V.

PAPAVER RHOEAS

Brantwood, July 11th, 1875.1. Chancing to take up yesterday a favourite old book, Mavor's British Tourists, (London, 1798,) I found in its fourth volume a delightful diary of a journey made in 1782 through various parts of England, by Charles P. Moritz of Berlin.

And in the fourteenth page of this diary I find the following passage, pleasantly complimentary to England:—

"The slices of bread and butter which they give you with your tea are as thin as poppy leaves. But there is another kind of bread and butter usually eaten with tea, which is toasted by the fire, and is incomparably good. This is called 'toast.'"

I wonder how many people, nowadays, whose bread and butter was cut too thin for them, would think of comparing the slices to poppy leaves? But this was in the old days of travelling, when people did not whirl themselves past corn-fields, that they might have more time to walk on paving-stones; and understood that poppies did not mingle their scarlet among the gold, without some purpose of the poppy-Maker that they should be looked at.

Nevertheless, with respect to the good and polite German's poetically-contemplated, and finely æsthetic, tea, may it not be asked whether poppy leaves themselves, like the bread and butter, are not, if we may venture an opinion—too thin,—im-properly thin? In the last chapter, my reader was, I hope, a little anxious to know what I meant by saying that modern philosophers did not know the meaning of the word 'proper,' and may wish to know what I mean by it myself. And this I think it needful to explain before going farther.

2. In our English prayer-book translation, the first verse of the ninety-third Psalm runs thus: "The Lord is King; and hath put on glorious apparel." And although, in the future republican world, there are to be no lords, no kings, and no glorious apparel, it will be found convenient, for botanical purposes, to remember what such things once were; for when I said of the poppy, in last chapter, that it was "robed in the purple of the Cæsars," the words gave, to any one who had a clear idea of a Cæsar, and of his dress, a better, and even stricter, account of the flower than if I had only said, with Mr. Sowerby, "petals bright scarlet;" which might just as well have been said of a pimpernel, or scarlet geranium;—but of neither of these latter should I have said "robed in purple of Cæsars." What I meant was, first, that the poppy leaf looks dyed through and through, like glass, or Tyrian tissue; and not merely painted: secondly, that the splendour of it is proud,—almost insolently so. Augustus, in his glory, might have been clothed like one of these; and Saul; but not David, nor Solomon; still less the teacher of Solomon, when He puts on 'glorious apparel.'

3. Let us look, however, at the two translations of the same verse.

In the vulgate it is "Dominus regnavit; decorem indutus est;" He has put on 'becomingness,'—decent apparel, rather than glorious.

In the Septuagint it is ευπρεπειὰ—well-becomingness; an expression which, if the reader considers, must imply certainly the existence of an opposite idea of possible 'ill-becomingness,'—of an apparel which should, in just as accurate a sense, belong appropriately to the creature invested with it, and yet not be glorious, but inglorious, and not well-becoming, but ill-becoming. The mandrill's blue nose, for instance, already referred to,—can we rightly speak of this as 'ευπρεπειὰ'? Or the stings, and minute, colourless blossoming of the nettle? May we call these a glorious apparel, as we may the glowing of an alpine rose?

You will find on reflection, and find more convincingly the more accurately you reflect, that there is an absolute sense attached to such words as 'decent,' 'honourable,' 'glorious,' or 'καλος,' contrary to another absolute sense in the words 'indecent,' 'shameful,' 'vile,' or 'αἰσχρος.'

And that there is every degree of these absolute qualities visible in living creatures; and that the divinity of the Mind of man is in its essential discernment of what is καλον from what is αἰσχρον, and in his preference of the kind of creatures which are decent, to those which are indecent; and of the kinds of thoughts, in himself, which are noble, to those which are vile.

4. When therefore I said that Mr. Darwin, and his school,25 had no conception of the real meaning of the word 'proper,' I meant that they conceived the qualities of things only as their 'properties,' but not as their becomingnesses;' and seeing that dirt is proper to a swine, malice to a monkey, poison to a nettle, and folly to a fool, they called a nettle but a nettle, and the faults of fools but folly; and never saw the difference between ugliness and beauty absolute, decency and indecency absolute, glory or shame absolute, and folly or sense absolute.

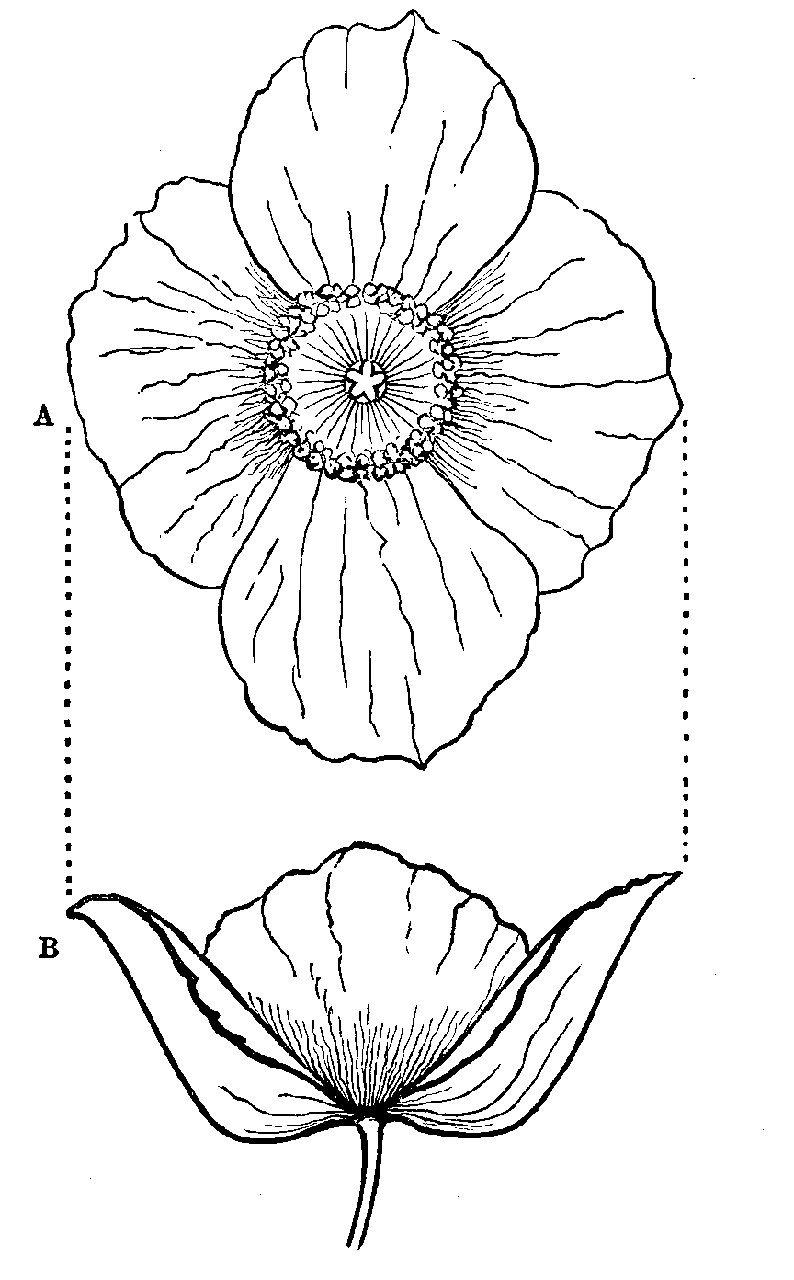

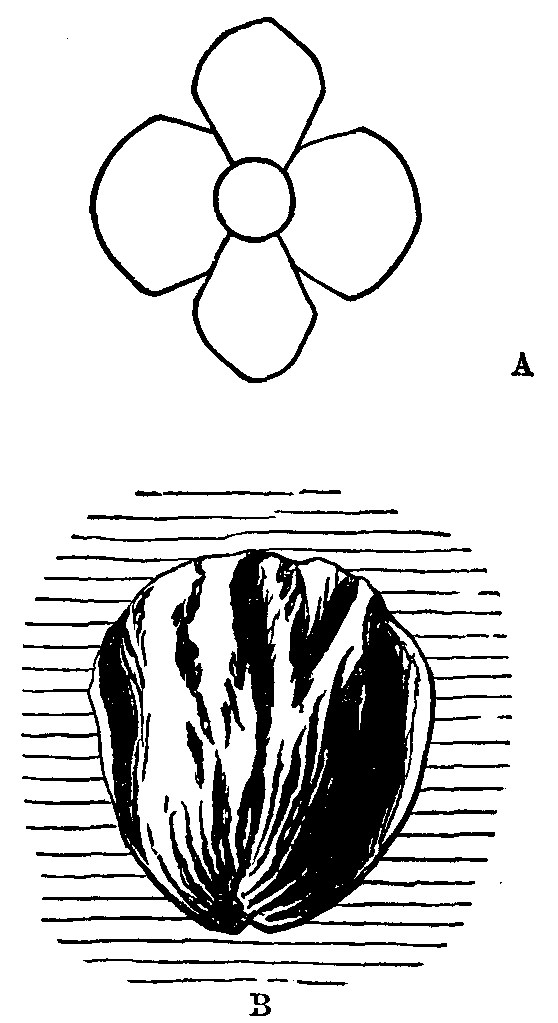

Fig. 10.

Whereas, the perception of beauty, and the power of defining physical character, are based on moral instinct, and on the power of defining animal or human character. Nor is it possible to say that one flower is more highly developed, or one animal of a higher order, than another, without the assumption of a divine law of perfection to which the one more conforms than the other.

5. Thus, for instance. That it should ever have been an open question with me whether a poppy had always two of its petals less than the other two, depended wholly on the hurry and imperfection with which the poppy carries out its plan. It never would have occurred to me to doubt whether an iris had three of its leaves smaller than the other three, because an iris always completes itself to its own ideal. Nevertheless, on examining various poppies, as I have walked, this summer, up and down the hills between Sheffield and Wakefield, I find the subordination of the upper and lower petals entirely necessary and normal; and that the result of it is to give two distinct profiles to the poppy cup, the difference between which, however, we shall see better in the yellow Welsh poppy, at present called Meconopsis Cambrica; but which, in the Oxford schools, will be 'Papaver cruciforme'—'Crosslet Poppy,'—first, because all our botanical names must be in Latin if possible; Greek only allowed when we can do no better; secondly, because meconopsis is barbarous Greek; thirdly, and chiefly, because it is little matter whether this poppy be Welsh or English; but very needful that we should observe, wherever it grows, that the petals are arranged in what used to be, in my young days, called a diamond shape,26 as at A, Fig. 10, the two narrow inner ones at right angles to, and projecting farther than, the two outside broad ones; and that the two broad ones, when the flower is seen in profile, as at B, show their margins folded back, as indicated by the thicker lines, and have a profile curve, which is only the softening, or melting away into each other, of two straight lines. Indeed, when the flower is younger, and quite strong, both its profiles, A and B, Fig. 11, are nearly straight-sided; and always, be it young or old, one broader than the other, so as to give the flower, seen from above, the shape of a contracted cross, or crosslet.

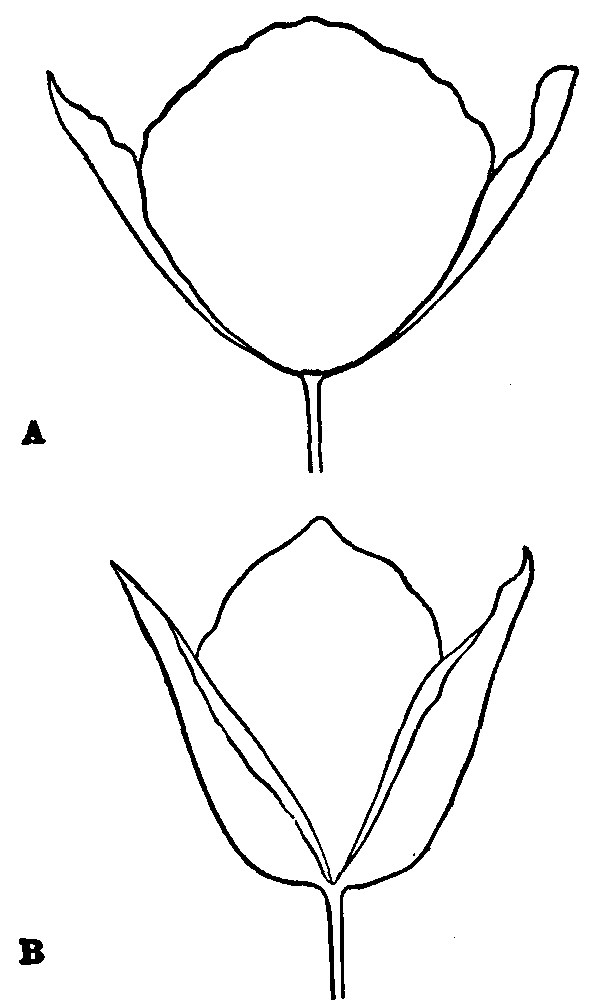

Fig. 11.

6. Now I find no notice of this flower in Gerarde; and in Sowerby, out of eighteen lines of closely printed descriptive text, no notice of its crosslet form, while the petals are only stated to be "roundish-concave," terms equally applicable to at least one-half of all flower petals in the world. The leaves are said to be very deeply pinnately partite; but drawn—as neither pinnate nor partite!

Fig. 12.

And this is your modern cheap science, in ten volumes. Now I haven't a quiet moment to spare for drawing this morning; but I merely give the main relations of the petals, A, and blot in the wrinkles of one of the lower ones, B, Fig. 12; and yet in this rude sketch you will feel, I believe, there is something specific which could not belong to any other flower. But all proper description is impossible without careful profiles of each petal laterally and across it. Which I may not find time to draw for any poppy whatever, because they none of them have well-becomingness enough to make it worth my while, being all more or less weedy, and ungracious, and mingled of good and evil. Whereupon rises before me, ghostly and untenable, the general question, 'What is a weed?' and, impatient for answer, the particular question, What is a poppy? I choose, for instance, to call this yellow flower a poppy, instead of a "likeness to poppy," which the botanists meant to call it, in their bad Greek. I choose also to call a poppy, what the botanists have called "glaucous thing," (glaucium). But where and when shall I stop calling things poppies? This is certainly a question to be settled at once, with others appertaining to it.

7. In the first place, then, I mean to call every flower either one thing or another, and not an 'aceous' thing, only half something or half another. I mean to call this plant now in my hand, either a poppy or not a poppy; but not poppaceous. And this other, either a thistle or not a thistle; but not thistlaceous. And this other, either a nettle or not a nettle; but not nettlaceous. I know it will be very difficult to carry out this principle when tribes of plants are much extended and varied in type: I shall persist in it, however, as far as possible; and when plants change so much that one cannot with any conscience call them by their family name any more, I shall put them aside somewhere among families of poor relations, not to be minded for the present, until we are well acquainted with the better bred circles; I don't know, for instance, whether I shall call the Burnet 'Grass-rose,' or put it out of court for having no petals; but it certainly shall not be called rosaceous; and my first point will be to make sure of my pupils having a clear idea of the central and unquestionable forms of thistle, grass, or rose, and assigning to them pure Latin, and pretty English, names,—classical, if possible; and at least intelligible and decorous.