полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

4. Funeral rites

The dead may be either buried or burnt, as convenient, and mourning is always observed for three days. Before the corpse is removed a new earthen pot filled with rice is placed on the bier. The chief mourner raises it, and addressing the deceased informs him that after a certain period he will be united to the sainted dead, and until that day his spirit should abide happily in the pot and not trouble his family. The mouth of the pot is then covered, and after the funeral the mourners take it home with them. When the day appointed for the final ceremony has come, a miniature platform is made from sticks tied together, and garlands and offerings of cakes are hung on to it. A small heap of rice is made on the platform, and just above it a clove is suspended from a thread. Songs are sung, and the principal relative opens the pot in which the spirit of the deceased has been enclosed. The spirit is called upon to join the sacred company of the dead, and the party continue to sing and to adjure it with all their force. The thread from which the clove is suspended begins to swing backwards and forwards over the rice; and a pig and two or three chickens are crushed to death as offerings to the soul of the deceased. Finally the clove touches the rice, and it is believed that the spirit of the dead man has departed to join the sainted dead. The Katias consider that after this he requires nothing more from the living, and so they do not make the annual offerings to the souls of the departed.

5. Social rules

The caste sometimes employ a Brāhman for the marriage ceremony; but generally his services are limited to fixing an auspicious date, and the functions of a priest are undertaken by members of the family. They invite a Brāhman to give a name to a boy, and call him by this name. They think that if they changed the name they would not be able to get a wife for the child. They will eat any kind of flesh, including pork and fowls, but they are not considered to be impure. They are generally illiterate, and dirty in appearance. Unmarried girls wear glass bangles on both hands, but married women wear metal bracelets on the right hand and glass on the left. Girls are twice tattooed: first in childhood, and a second time after marriage. The proper avocations of the Katias were the spinning of cotton thread and the weaving of the finer kinds of cloth; but most of them have had to abandon their ancestral calling from want of custom, and they are now either village watchmen or cultivators and labourers. A few of them own villages. The Katias think themselves rather knowing; but this opinion is not shared by their neighbours, who say ironically of them, “A Katia is eight times as wise as an ordinary man, and a Kāyasth thirteen times. Any one who pretends to be wiser than these must be an idiot.”

Kawar417

1. Tribal legend

Kawar, Kanwar, Kaur (honorific title, Sirdār).—A primitive tribe living in the hills of the Chhattīsgarh Districts north of the Mahānadi. The hill-country comprised in the northern zamīndāri estates of Bilāspur and the adjoining Feudatory States of Jashpur, Udaipur, Sargūja, Chāng Bhakār and Korea is the home of the Kawars, and is sometimes known after them as the Kamrān. Eight of the Bilāspur zamīndārs are of the Kawar tribe. The total numbers of the tribe are nearly 200,000, practically all of whom belong to the Central Provinces. In Bilāspur the name is always pronounced with a nasal as Kanwar. The Kawars trace their origin from the Kauravas of the Mahābhārata, who were defeated by the Pāndavas at the great battle of Hastināpur. They say that only two pregnant women survived and fled to the hills of Central India, where they took refuge in the houses of a Rāwat (grazier) and a Dhobi (washerman) respectively, and the boy and girl children who were born to them became the ancestors of the Kawar tribe. Consequently, the Kawars will take food from the hands of Rāwats, especially those of the Kauria subcaste, who are in all probability descended from Kawars. And when a Kawar is put out of caste for having maggots in a wound, a Dhobi is always employed to readmit him to social intercourse. These facts show that the tribe have some close ancestral connection with the Rāwats and Dhobis, though the legend of descent from the Kauravas is, of course, a myth based on the similarity of the names. The tribe have lost their own language, if they ever had one, and now speak a corrupt form of the Chhattīsgarhi dialect of Hindi. It is probable that they belong to the Dravidian tribal family.

2. Tribal subdivisions

The Kawars have the following eight endogamous divisions: Tanwar, Kamalbansi, Paikara, Dūdh-Kawar, Rathia, Chānti, Cherwa and Rautia. The Tanwar group, also known as Umrao, is that to which the zamīndārs belong, and they now claim to be Tomara Rājpūts, and wear the sacred thread. They prohibit widow-remarriage, and do not eat fowls or drink liquor; but they have not yet induced Brāhmans to take water from them or Rājpūts to accept their daughters in marriage. The name Tanwar is not improbably simply a corruption of Kawar, and they are also altering their sept names to make them resemble those of eponymous Brāhmanical gotras. Thus Dhangur, the name of a sept, has been altered to Dhananjaya, and Sarvaria to Sāndilya. Telāsi is the name of a sept to which four zamīndārs belong, and is on this account sometimes returned as their caste by other Kawars, who consider it as a distinction. The zamīndāri families have now, however, changed the name Telāsi to Kairava. The Paikaras are the most numerous subtribe, being three-fifths of the total. They derive their name from Pāik, a foot-soldier, and formerly followed this occupation, being employed in the armies of the Haihaivansi Rājas of Ratanpur. They still worship a two-edged sword, known as the Jhagra Khand, or ‘Sword of Strife,’ on the day of Dasahra. The Kamalbansi, or ‘Stock of the Lotus,’ may be so called as being the oldest subdivision; for the lotus is sometimes considered the root of all things, on account of the belief that Brahma, the creator of the world, was himself born from this flower. In Bilāspur the Kamalbansis are considered to rank next after the Tanwars or zamīndārs’ group. Colonel Dalton states that the term Dūdh or ‘Milk’ Kawar has the signification of ‘Cream of the Kawars,’ and he considered this subcaste to be the highest. The Rathias are a territorial group, being immigrants from Rāth, a wild tract of the Raigarh State. The Rautias are probably the descendants of Kawar fathers and mothers of the Rāwat (herdsman) caste. The traditional connection of the Kawars with a Rāwat has already been mentioned, and even now if a Kawar marries a Rāwat girl she will be admitted into the tribe, and the children will become full Kawars. Similarly, the Rāwats have a Kauria subcaste, who are also probably the offspring of mixed marriages; and if a Kawar girl is seduced by a Kauria Rāwat, she is not expelled from the tribe, as she would be for a liaison with any other man who was not a Kawar. This connection is no doubt due to the fact that until recently the Kawars and Rāwats, who are themselves a very mixed caste, were accustomed to intermarry. At the census persons returned as Rautia were included in the Kol tribe, which has a subdivision of that name. But Mr. Hīra Lāl’s inquiries establish the fact that in Chhattīsgarh they are undoubtedly Kawars. The Cherwas are probably another hybrid group descended from connections formed by Kawars with girls of the Chero tribe of Chota Nāgpur. The Chānti, who derive their name from the ant, are considered to be the lowest group, as that insect is the most insignificant of living things. Of the above subcastes the Tanwars are naturally the highest, while the Chānti, Cherwa and Rautia, who keep pigs, are considered as the lowest. The others occupy an intermediate position. None of the subcastes will eat together, except at the houses of their zamīndārs, from whom they will all take food. But the Kawars of the Chhuri estate no longer attend the feasts of their zamīndār, for the following curious reason. One of the latter’s village thekādārs or farmers had got the hide taken off a dead buffalo so as to keep it for his own use, instead of making the body over to a Chamār (tanner). The caste-fellows saw no harm in this act, but it offended the zamīndār’s more orthodox Hindu conscience. Soon afterwards, at some marriage-feast of his family, when the Kawars of his zamīndāri attended in accordance with the usual custom, he remarked, ‘Here come our Chamārs,’ or words to that effect. The Chhuri Kawars were insulted, and the more so because the Pendra zamīndār and other outsiders were present. So they declined to take food any longer from their zamīndār. They continued to accept it, however, from the other zamīndārs, until their master of Chhuri represented to them that this would result in a slur being put upon his standing among his fellows. So they have now given up taking food from any zamīndār.

3. Exogamous groups

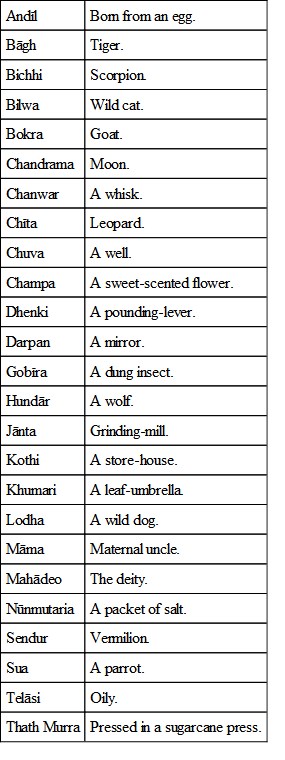

The tribe have a large number of exogamous septs, which are generally totemistic or named after plants and animals. The names of 117 septs have been recorded, and there are probably even more. The following list gives a selection of the names:

Generally it may be said that every common animal or bird and even articles of food or dress and household implements have given their names to a sept. In the Paikara subcaste a figure of the plant or animal after which the sept is named is made by each party at the time of marriage. Thus a bridegroom of the Bāgh or tiger sept prepares a small image of a tiger with flour and bakes it in oil; this he shows to the bride’s family to represent, as it were, his pedigree, or prove his legitimacy; while she on her part, assuming that she is, say, of the Bilwa or cat sept, will bring a similar image of a cat with her in proof of her origin. The Andīl sept make a representation of a hen sitting on eggs. They do not worship the totem animal or plant, but when they learn of the death of one of the species, they throw away an earthen cooking-pot as a sign of mourning. They generally think themselves descended from the totem animal or plant, but when the sept is called after some inanimate object, such as a grinding-mill or pounding-lever, they repudiate the idea of descent from it, and are at a loss to account for the origin of the name. Those whose septs are named after plants or animals usually abstain from injuring or cutting them, but where this rule would cause too much inconvenience it is transgressed: thus the members of the Karsāyal or deer sept find it too hard for them to abjure the flesh of that animal, nor can those of the Bokra sept abstain from eating goats. In some cases new septs have been formed by a conjunction of the names of two others, as Bāgh-Daharia, Gauriya-Sonwāni, and so on. These may possibly be analogous to the use of double names in English, a family of one sept when it has contracted a marriage with another of better position adding the latter’s name to its own as a slight distinction. But it may also simply arise from the constant tendency to increase the number of septs in order to remove difficulties from the arrangement of matches.

4. Betrothal and marriage

Marriage within the same sept is prohibited and also between the children of brothers and sisters. A man may not marry his wife’s elder sister but he can take her younger one in her lifetime. Marriage is usually adult and, contrary to the Hindu rule, the proposal for a match always comes from the boy’s father, as a man would think it undignified to try and find a husband for his daughter. The Kawar says, ‘Shall my daughter leap over the wall to get a husband.’ In consequence of this girls not infrequently remain unmarried until a comparatively late age, especially in the zamīndāri families where the provision of a husband of suitable rank may be difficult. Having selected a bride for his son the boy’s father sends some friends to her village, and they address a friend of the girl’s family, saying, “So-and-so (giving his name and village) would like to have a cup of pej (boiled rice-water) from you; what do you say?” The proposal is communicated to the girl’s family, and if they approve of it they commence preparing the rice-water, which is partaken of by the parties and their friends. If the bride’s people do not begin cooking the pej, it is understood that the proposal is rejected. The ceremony of betrothal comes next, when the boy’s party go to the girl’s house with a present of bangles, clothes, and fried cakes of rice and urad carried by a Kaurai Rāwat. They also take with them the bride-price, known as Suk, which is made up of cash, husked or unhusked rice, pulses and oil. It is a fixed amount, but differs for each subcaste, and the average value is about Rs. 25. To this is added three or four goats to be consumed at the wedding. If a widower marries a girl, a larger bride-price is exacted. The wedding follows, and in many respects conforms to the ordinary Hindu ritual, but Brāhmans are not employed. The bridegroom’s party is accompanied by tomtom-players on its way to the wedding, and as each village is approached plenty of noise is made, so that the residents may come out and admire the dresses, a great part of whose merit consists in their antiquity, while the wearer delights in recounting to any who will listen the history of his garb and of his distinguished ancestors who have worn it. The marriage is performed by walking round the sacred pole, six times on one day and once on the following day. After the marriage the bride’s parents wash the feet of the couple in milk, and then drink it in atonement for the sin committed in bringing their daughter into the world. The couple then return home to the bridegroom’s house, where all the ceremonies are repeated, as it is said that otherwise his courtyard would remain unmarried. On the following day the couple go and bathe in a tank, where each throws five pots full of water over the other. And on their return the bridegroom shoots arrows at seven straw images of deer over his wife’s shoulder, and after each shot she puts a little sugar in his mouth. This is a common ceremony among the forest tribes, and symbolises the idea that the man will support himself and his wife by hunting. On the fourth day the bride returns to her father’s house. She visits her husband for two or three months in the following month of Asārh (June–July), but again goes home to play what is known as ‘The game of Gauri,’ Gauri being the name of Siva’s consort. The young men and girls of the village assemble round her in the evening, and the girls sing songs while the men play on drums. An obscene representation of Gauri is made, and some of them pretend to be possessed by the deity, while the men beat the girls with ropes of grass. After she has enjoyed this amusement with her mates for some three months, the bride finally goes to her husband’s house.

5. Other customs connected with marriage

The wedding expenses come to about seventy rupees on the bridegroom’s part in an ordinary marriage, while the bride’s family spend the amount of the bride-price and a few rupees more. If the parties are poor the ceremony can be curtailed so far as to provide food for only five guests. It is permissible for two families to effect an exchange of girls in lieu of payment of the bride-price, this practice being known as Gunrāwat. Or a prospective bridegroom may give his services for three or four years instead of a price. The system of serving for a wife is known as Gharjiān, and is generally resorted to by widows having daughters. A girl going wrong with a Kawar or with a Kaurai Rāwat before marriage may be pardoned with the exaction of a feast from her parents. For a liaison with any other outsider she is finally expelled, and the exception of the Kaurai Rāwats shows that they are recognised as in reality Kawars. Widow-remarriage is permitted except in the Tanwar subcaste. New bangles and clothes are given to the widow, and the pair then stand under the eaves of the house; the bridegroom touches the woman’s ear or puts a rolled mango-leaf into it, and she becomes his wife. If a widower marries a girl for his third wife it is considered unlucky for her. An earthen image of a woman is therefore made, and he goes through the marriage ceremony with it; he then throws the image to the ground so that it is broken, when it is considered to be dead and its funeral ceremony is performed. After this the widower may marry the girl, who becomes his fourth wife. Such cases are naturally very rare. If a widow marries her deceased husband’s younger brother, which is considered the most suitable match, the children by her first husband rank equally with those of the second. If she marries outside the family her children and property remain with her first husband’s relatives.

Dalton418 records that the Kawars of Sargūja had adopted the practice of sati: “I found that the Kawars of Sargūja encouraged widows to become Satis and greatly venerated those who did so. Sati shrines are not uncommon in the Tributary Mahāls. Between Partābpur and Jhilmili in Sargūja I encamped in a grove sacred to a Kauraini Sati. Several generations have elapsed since the self-sacrifice that led to her canonisation, but she is now the principal object of worship in the village and neighbourhood, and I was informed that every year a fowl was sacrificed to her, and every third year a black goat. The Hindus with me were intensely amused at the idea of offering fowls to a Sati!” Polygamy is permitted, but is not common. Members of the Tanwar subtribe, when they have occasion to do so, will take the daughters of Kawars of other groups for wives, though they will not give their daughters to them. Such marriages are generally made clandestinely, and it has become doubtful as to whether some families are true Tanwars. The zamīndārs have therefore introduced a rule that no family can be recognised as a Tanwar for purposes of marriage unless it has a certificate to that effect signed by the zamīndār. Some of the zamīndārs charge considerable sums for these certificates, and all cannot afford them; but in that case they are usually unable to get husbands for their daughters, who remain unwed. Divorce is permitted for serious disagreement or bad conduct on the part of the wife.

6. Childbirth

During childbirth the mother sits on the ground with her legs apart, and her back against the wall or supported by another woman. The umbilical cord is cut by the midwife: if the parents wish the boy to become eloquent she buries it in the village Council-place; or if they wish him to be a good trader, in the market; or if they desire him to be pious, before some shrine; in the case of a girl the cord is usually buried in a dung-heap, which is regarded as an emblem of fertility. As is usual in Chhattīsgarh, the mother receives no food or water for three days after the birth of a child. On the fifth day she is given regular food and on that day the house is purified. Five months after birth the lips of the child are touched with rice and milk and it is named. When twins are born a metal vessel is broken to sever the connection between them, as it is believed that otherwise they must die at the same time. If a boy is born after three girls he is called titura, and a girl after three boys, tituri. There is a saying that ‘A titura child either fills the storehouse or empties it’; that is, his parents either become rich or penniless. To avert ill-luck in this case oil and salt are thrown away, and the mother gives one of her bangles to the midwife.

7. Disposal of the dead

The dead are usually buried, though well-to-do families have adopted cremation. The corpse is laid on its side in the grave, with head to the north and face to the east. A little til, cotton, urad and rice are thrown on the grave to serve as seed-grain for the dead man’s cultivation in the other world. A dish, a drinking vessel and a cooking-pot are placed on the grave with the same idea, but are afterwards taken away by the Dhobi (washerman). They observe mourning for ten days for a man, nine days for a woman, and three days for children under three years old. During the period of mourning the chief mourner keeps a knife beside him, so that the iron may ward off the attacks of evil spirits, to which he is believed to be peculiarly exposed. The ordinary rules of abstinence and retirement are observed during mourning. In the case of cremation the ceremonies are very elaborate and generally resemble those of the Hindus. When the corpse is half burnt, all the men present throw five pieces of wood on to the pyre, and a number of pieces are carried in a winnowing fan to the dead man’s house, where they are touched by the women and then brought back and thrown on to the fire. After the funeral the mourners bathe and return home walking one behind the other in Indian file. When they come to a cross-road, the foremost man picks up a pebble with his left foot, and it is passed from hand to hand down the line of men until the hindmost throws it away. This is supposed to sever their connection with the spirit of the deceased and prevent it from following them home. On the third day they return to the cremation ground to collect the ashes and bones. A Brāhman is called who cooks a preparation of milk and rice at the head of the corpse, boils urad pulse at its feet, and bakes eight wheaten chapātis at the sides. This food is placed in leaf-cups at two corners of the ground. The mourners sprinkle cow’s urine and milk over the bones, and picking them up with a palās (Butea frondosa) stick, wash them in milk and deposit them in a new earthen pot until such time as they can be carried to the Ganges. The bodies of men dying of smallpox must never be burnt, because that would be equivalent to destroying the goddess, incarnate in the body. The corpses of cholera patients are buried in order to dispose of them at once, and are sometimes exhumed subsequently within a period of six months and cremated. In such a case the Kawars spread a layer of unhusked rice in the grave, and address a prayer to the earth-goddess stating that the body has been placed with her on deposit, and asking that she will give it back intact when they call upon her for it. They believe that in such cases the process of decay is arrested for six months.

8. Laying spirits

When a man has been killed by a tiger they have a ceremony called ‘Breaking the string,’ or the connection which they believe the animal establishes with a family on having tasted its blood. Otherwise they think that the tiger would gradually kill off all the remaining members of the family of his victim, and when he had finished with them would proceed to other families in the same village. This curious belief is no doubt confirmed by the tiger’s habit of frequenting the locality of a village from which it has once obtained a victim, in the natural expectation that others may be forthcoming from the same source. In this ceremony the village Baiga or medicine-man is painted with red ochre and soot to represent the tiger, and proceeds to the place where the victim was carried off. Having picked up some of the blood-stained earth in his mouth, he tries to run away to the jungle, but the spectators hold him back until he spits out the earth. This represents the tiger being forced to give up his victim. The Baiga then ties a string round all the members of the dead man’s family standing together; he places some grain before a fowl saying, ‘If my charm has worked, eat of this’; and as soon as the fowl has eaten some grain the Baiga states that his efforts have been successful and the attraction of the man-eater has been broken; he then breaks the string and all the party return to the village. A similar ceremony is performed when a man has died of snake-bite.

9. Religion

The religion of the Kawars is entirely of an animistic character. They have a vague idea of a supreme deity whom they call Bhagwān and identify with the sun. They bow to him in reverence, but do no more as he does not interfere with men’s concerns. They also have a host of local and tribal deities, of whom the principal is the Jhagra Khand or two-edged sword, already mentioned. The tiger is deified as Bagharra Deo and worshipped in every village for the protection of cattle from wild animals. They are also in great fear of a mythical snake with a red crest on its head, the mere sight of which is believed to cause death. It lives in deep pools in the forest which are known as Shesk Kund, and when it moves the grass along its track takes fire. If a man crosses its track his colour turns to black and he suffers excruciating pains which end in death, unless he is relieved by the Baiga. In one village where the snake was said to have recently appeared, the proprietor was so afraid of it that he never went out to his field without first offering a chicken. They have various local deities, of which the Mandwa Rāni or goddess of the Mandwa hill in Korba zamīndāri may be noticed as an example. She is a mild-hearted maiden who puts people right when they have gone astray in the forest, or provides them with food for the night and guides them to the water-springs on her hill. Recently a wayfarer had lost his path when she appeared and, guiding him into it, gave him a basket of brinjāls.419 As the traveller proceeded he felt his burden growing heavier and heavier on his head, and finally on inspecting it found that the goddess had played a little joke on him and the brinjāls had turned into stones. The Kawars implicitly believe this story. Rivers are tenanted by a set of goddesses called the Sat Bahini or seven sisters. They delight in playing near waterfalls, holding up the water and suddenly letting it drop. Trees are believed to be harmless sentient beings, except when occasionally possessed by evil spirits, such as the ghosts of man-eating tigers. Sometimes a tree catches hold of a cow’s tail as the animal passes by and winds it up over a branch, and many cattle have lost their tails in this way. Every tank in which the lotus grows is tenanted by Purainha, the godling who tends this plant. The sword, the gun, the axe, the spear have each a special deity, and, in fact, in the Bangawān, the tract where the wilder Kawars dwell, it is believed that every article of household furniture is the residence of a spirit, and that if any one steals or injures it without the owner’s leave, the spirit will bring some misfortune on him in revenge. Theft is said to be unknown among them, partly on this account and partly, perhaps, because no one has much property worth stealing. Instances of deified human beings are Kolin Sati, a Kol concubine of a zamīndār of Pendra who died during pregnancy, and Sārangarhni, a Ghasia woman who was believed to have been the mistress of a Rāja of Sārangarh and was murdered. Both are now Kawar deities. Thākur Deo is the deity of agriculture, and is worshipped by the whole village in concert at the commencement of the rains. Rice is brought by each cultivator and offered to the god, a little being sown at his shrine and the remainder taken home and mixed with the seed-grain to give it fertility. Two bachelors carry water round the village and sprinkle it on the brass plates of the cultivators or the roofs of their houses in imitation of rain.