полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 3

19. Sanctity of domestic animals

Thus it was a more or less general rule among several races that the domestic animals were deified and held sacred, and were slain only at a sacrifice. It followed that it was sinful to kill these animals on any other occasion. It has already been seen that the Arabs forbore to kill their worn-out camels for food except when driven to it by hunger as a last resort. “That it was once a capital offence to kill an ox, both in Attica and the Peloponnesus, is attested by Varro. So far as Athens is concerned, this statement seems to be drawn from the legend that was told in connection with the annual sacrifice at the Diipolia, where the victim was a bull and its death was followed by a solemn inquiry as to who was responsible for the act. In this trial everyone who had anything to do with the slaughter was called as a party; the maidens who drew water to sharpen the axe and knife threw the blame on the sharpeners, they put it on the man who handed the axe, he on the man who struck down the victim, and he again on the one who cut its throat, who finally fixed the responsibility on the knife, which was accordingly found guilty of murder and cast into the sea.”374 “At Tenedos the priest who offered a bull-calf to Dionysus anthroporraistes was attacked with stones and had to flee for his life; and at Corinth, in the annual sacrifice of a goat to Hera Acraea, care was taken to shift the responsibility of the death off the shoulders of the community by employing hirelings as ministers. Even they did no more than hide the knife in such a way that the goat, scraping with its feet, procured its own death.”375 “Agatharchides, describing the Troglodytes of East Africa, a primitive pastoral people in the polyandrous state of society, tells us that their whole sustenance was derived from their flocks and herds. When pasture abounded, after the rainy season, they lived on milk mingled with blood (drawn apparently, as in Arabia, from the living animal), and in the dry season they had recourse to the flesh of aged or weakly beasts. Further, ‘they gave the name of parent to no human being, but only to the ox and cow, the ram and ewe, from whom they had their nourishment.’ Among the Caffres the cattle kraal is sacred; women may not enter it, and to defile it is a capital offence.”376 Among the Egyptians also cows were never killed.377

20. Sacrificial slaughter for food

Gradually, however, as the reverence for animals declined and the true level of their intelligence compared to that of man came to be better appreciated, the sanctity attaching to their lives no doubt grew weaker. Then it would become permissible to kill a domestic animal privately and otherwise than by a joint sacrifice of the clan; but the old custom of justifying the slaughter by offering it to the god would still remain. “At this stage,378 at least among the Hebrews, the original sanctity of the life of domestic animals is still recognised in a modified form, inasmuch as it is held unlawful to use their flesh for food except in a sacrificial meal. But this rule is not strict enough to prevent flesh from becoming a familiar luxury. Sacrifices are multiplied on trivial occasions of religious gladness or social festivity, and the rite of eating at the sanctuary loses the character of an exceptional sacrament, and means no more than that men are invited to feast and be merry at the table of their god, or that no feast is complete in which the god has not his share.”379 This is the stage reached by the Hebrews in the time of Samuel, as described by Professor Robertson Smith, and it bears much resemblance to that of the lower Hindu castes and the Gonds at the present time. They too, when they can afford to kill a goat or a pig, cows being prohibited in deference to Hindu susceptibility, take it to the shrine of some village deity and offer it there prior to feasting on it with their friends. At intervals of a year or more many of the lower castes sacrifice a goat to Dūlha Deo, the bridegroom-god, and Thākur Deo, the corn-god, and eat the body as a sacrificial meal within the house, burying the bones and other remnants beneath the floor of the house.380 Among the Kāfirs of the Hindu Kush, when a man wishes to become a Jast, apparently a revered elder or senator, he must give a series of feasts to the whole community, so expensive that many men utterly ruin themselves in becoming Jast. The initiatory proceedings are sacrifices of bulls and male goats to Gīsh, the war-god, at the village shrine. The animals are examined with jealous eyes by the spectators, to see that they come up to the prescribed standard of excellence. After the sacrifice the meat is divided among the people, who carry it to their homes. These special sacrifices at the shrine recur at intervals; but the great slaughterings are at the feast-giver’s own house, where he entertains sometimes the Jast exclusively and sometimes the whole tribe, as already mentioned.381 Even in the latter case, however, after a big distribution at the giver’s house one or two goats are offered to the war-god at his shrine; and while the animals are being killed at the house offerings are made on a sacrificial fire, and as each goat is slain a handful of its blood is taken and thrown on the fire.382 The Kāfirs would therefore appear to be in the stage when it is still usual to kill domestic animals as a sacrifice to the god, but no longer obligatory.

21. Animal fights

Finally animals are recognised for what they are, all sanctity ceases to attach to them, and they are killed for food in an ordinary manner. Possibly, however, such customs as roasting an ox whole, and the sports of bull-baiting and bull-fighting, may be relics of the ancient sacrifice. Formerly the buffaloes sacrificed at the shrine of the goddess Rankini or Kāli in Dalbhūm zamīndāri of Chota Nāgpur were made to fight. “Two male buffaloes are driven into a small enclosure and on a raised stage adjoining and overlooking it the Rāja and his suite take up their position. After some ceremonies the Rāja and his family priest discharge arrows at the buffaloes, others follow their example, and the tormented and enraged beasts fall to and gore each other whilst arrow after arrow is discharged. When the animals are past doing very much mischief, the people rush in and hack at them with battle-axes till they are dead.”383

22. The sacrificial method of killing

Muhammadans however cannot eat the flesh of an animal unless its throat is cut and the blood allowed to flow before it dies. At the time of cutting the throat a sacred text or invocation must be repeated. It has been seen that in former times the blood of the animal was offered to the god and scattered on the altar or collected in a pit at its foot. It may be suggested that the method of killing which still survives was that formerly practised in offering the sacrifice, and that the necessity of allowing the blood to flow is a relic of the blood offering. When it no longer became necessary to sacrifice every animal at a shrine the sacrificial method of slaughter and the invocation to the god might be retained as removing the impiety of the act. At present it is said that unless an animal’s blood flows it is a murda or corpse, and hence not suitable for food. But this idea may have grown up to account for the custom when its original meaning had been forgotten. The Gonds, when sacrificing a fowl, hold it over the sacred post or stone, which represents the god, and let the blood drop upon it. And when sacrificing a pig they first cut its tongue and let the blood fall upon the symbol of the god. In Chhattīsgarh, when a Hindu is ill he makes a vow of the affected limb to the god; then on recovering he goes to the temple, and cutting this limb, lets the blood fall on to the symbol of the god as an offering. Similarly the Sikhs are forbidden to eat flesh unless the animal has been killed by jatka or cutting off the head with one stroke, and the same rule is observed by some of the lower Hindu castes. In Hindu sacrifices it is often customary that the head of the animal should be made over to the officiating priest as his share, and so in killing the animal he would naturally cut off its head. The above rule may therefore be of the same character as the rite of halāl among the Muhammadans, and here also the sacrificial method of killing an animal may be retained to legalise its slaughter after the sacrifice itself has fallen into desuetude. In Berār some time ago the Mullah or Muhammadan priest was a village servant and the Hindus paid him dues. In return he was accustomed to kill the goats and sheep which they wished to sacrifice at temples, or in their fields to propitiate the deities presiding over them. He also killed animals for the Khatīk or mutton-butcher and the latter exposed them for sale. The Mullah was entitled to the heart of the animal killed as his perquisite and a fee of two pice. Some of the Marāthas were unmindful of the ceremony, but in general they professed not to eat flesh unless the sacred verse had been pronounced either by the Mullah or some Muhammadan capable of rendering it halāl or lawful to be eaten.384 Hence it would appear that the Hindus, unprovided by their own religion with any sacrificial mode of legalising the slaughter of animals, adopted the ritual of a foreign faith in order to make animal sacrifices acceptable to their own deities. The belief that it is sinful to kill a domestic animal except with some religious sanction is thus clearly shown in full force.

23. Animal sacrifices in Indian ritual

Among high-caste Hindus also sacrifices, including the killing of cows, were at one time legal. This is shown by several legends,385 and is also a historical fact. One of Asoka’s royal edicts prohibited at the capital the celebration of animal sacrifices and merry-makings involving the use of meat, but in the provinces apparently they continued to be lawful.386 This indicates that prior to the rise of Buddhism such sacrifices had been customary, and also that when a feast was to be given, involving the consumption of meat, the animal was offered as a sacrifice. It is noteworthy that Asoka’s rules do not forbid the slaughter of cows.387 In ancient times also the most important royal sacrifice was that of the horse. The development of religious belief and practice in connection with the killing of domestic animals has thus proceeded on exactly opposite lines in India as compared with most of the world. Domestic animals have become more instead of less sacred and several of them cannot be killed at all. The reason usually given to account for this is the belief in the transmigration of souls, leading to the conclusion that the bodies of animals might be tenanted by human souls. Probably also Buddhism left powerful traces of its influence on the Hindu view of the sanctity of animal life even after it had ceased to be the state religion. Perhaps the Brāhmans desired to make their faith more popular and took advantage of the favourite reverence of all cultivators for the cow to exalt her into one of their most powerful deities, and at the same time to extend the local cult of Krishna, the divine cowherd, thus following exactly the contrary course to that taken by Moses with the golden calf. Generally the growth of political and national feeling has mainly operated to limit the influence of the priesthood, and the spread of education and development of reasoned criticism and discussion have softened the strictness of religious observance and ritual. Both these factors have been almost entirely wanting in Hindu society, and this perhaps explains the continued sanctity attaching to the lives of domestic animals as well as the unabated power of the caste system.

Kasār

1. Distribution and origin of the caste

Kasār, Kasera, Kansari, Bharewa.388—The professional caste of makers and sellers of brass and copper vessels. In 1911 the Kasārs numbered 20,000 persons in the Central Provinces and Berār, and were distributed over all Districts, except in the Jubbulpore division, where they are scarcely found outside Mandla. Their place in the other Districts of this division is taken by the Tameras. In Mandla the Kasārs are represented by the inferior Bharewa group. The name of the caste is derived from kānsa, a term now applied to bell-metal. The kindred caste of Tameras take their name from tāmba, copper, but both castes work in this metal indifferently, and in Saugor, Damoh and Jubbulpore no distinction exists between the Kasārs and Tameras, the same caste being known by both names. A similar confusion exists in northern India in the use of the corresponding terms Kasera and Thathera.389 In Wardha the Kasārs are no longer artificers, but only dealers, employing Panchāls to make the vessels which they retail in their shops. And the same is the case with the Marātha and Deshkar subcastes in Nāgpur. The Kasārs are a respectable caste, ranking next to the Sunārs among the urban craftsmen.

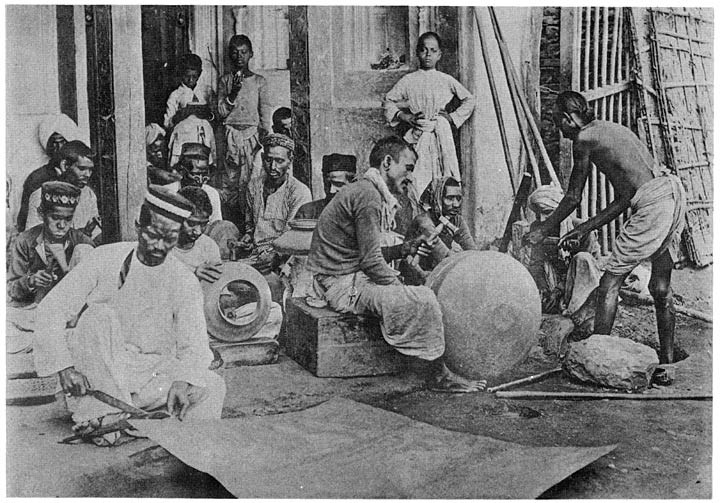

A group of Kasārs or brass-workers

According to a legend given by Mr. Sadāsheo Jairām they trace their origin from Dharampāl, the son of Sahasra Arjun or Arjun of the Thousand Arms. Arjun was the greatgrandson of Ekshvaku, who was born in the forests of Kalinga, from the union of a mare and a snake. On this account the Kasārs of the Marātha country say that they all belong to the Ahihaya clan (Ahi, a snake; and Haya, a mare). Arjun was killed by Parasurāma during the slaughter of the Kshatriyas and Dharampāl’s mother escaped with three other pregnant women. According to another version all the four women were the wives of the king of the Somvansi Rājpūts who stole the sacred cow Kāmdhenu. Their four sons on growing up wished to avenge their father and prayed to the Goddess Kāli for weapons. But unfortunately in their prayer, instead of saying bān, arrow, they said vān, which means pot, and hence brass pots were given to them instead of arrows. They set out to sell the pots, but got involved in a quarrel with a Rāja, who killed three of them, but was defeated by the fourth, to whom he afterwards gave his daughter and half his kingdom; and this hero became the ancestor of the Kasārs. In some localities the Kasārs say that Dharampāl, the Rājpūt founder of their caste, was the ancestor of the Haihaya Rājpūt kings of Ratanpur; and it is noticeable that the Thatheras of the United Provinces state that their original home was a place called Ratanpur, in the Deccan.390 Both Ratanpur and Mandla, which are very old towns, have important brass and bell-metal industries, their bell-metal wares being especially well known on account of the brilliant polish which is imparted to them. And the story of the Kasārs may well indicate, as suggested by Mr. Hīra Lāl, that Ratanpur was a very early centre of the brass-working industry, from which it has spread to other localities in this part of India.

2. Internal structure

The caste have a number of subdivisions, mainly of a territorial nature. Among these are the Marātha Kasārs; the Deshkar, who also belong to the Marātha country; the Pardeshi or foreigners, the Jhāde or residents of the forest country of the Central Provinces, and the Audhia or Ajudhiabāsi who are immigrants from Oudh. Another subdivision, the Bharewas, are of a distinctly lower status than the body of the caste, and have non-Aryan customs, such as the eating of pork. They make the heavy brass ornaments which the Gonds and other tribes wear on their legs, and are probably an occupational offshoot from one of these tribes. In Chānda some of the Bharewas serve as grooms and are looked down upon by the others. They have totemistic septs, named after animals and plants, some of which are Gond words; and among them the bride goes to the bridegroom’s house to be married, which is a Gond custom. The Bharewas may more properly be considered as a separate caste of lower status. As previously stated, the Marātha and Deshkar subcastes of the Marātha country no longer make vessels, but only keep them for sale. One subcaste, the Otāris, make vessels from moulds, while the remainder cut and hammer into shape the imported sheets of brass. Lastly comes a group comprising those members of the caste who are of doubtful or illegitimate descent, and these are known either as Tākle (‘Thrown out’ in Marāthi), Bidur, ‘Bastard,’ or Laondi Bachcha, ‘Issue of a kept wife.’ In the Marātha country the Kasārs, as already seen, say that they all belong to one gotra, the Ahihaya. They have, however, collections of families distinguished by different surnames, and persons having the same surname are forbidden to marry. In the northern Districts they have the usual collection of exogamous septs, usually named after villages.

3. Social customs

The marriages of first cousins are generally forbidden, as well as of members of the same sept. Divorce and the remarriage of widows are permitted. Devi or Bhawāni is the principal deity of the caste, as of so many Hindus. At her festival of Māndo Amāwas or the day of the new moon of Phāgun (February), every Kasār must return to the community of which he is a member and celebrate the feast with them. And in default of this he will be expelled from caste until the next Amāwas of Phāgun comes round. They close their shops and worship the implements of their trade on this day and also on the Pola day. The Kasārs, as already stated, rank next to the Sunārs among the artisan castes, and the Audhia Sunārs, who make ornaments of bell-metal, form a connecting link between the two groups. The social status of the Kasārs varies in different localities. In some places Brāhmans take water from them but not in others. Some Kasārs now invest boys with the sacred thread at their weddings, and thereafter it is regularly worn.

4. Occupation

The caste make eating and drinking vessels, ornaments and ornamental figures from brass, copper and bell-metal. Brass is the metal most in favour for utensils, and it is usually imported in sheets from Bombay, but in places it is manufactured from a mixture of three parts of copper and two of zinc. This is considered the best brass, though it is not so hard as the inferior kinds, in which the proportion of zinc is increased. Ornaments of a grey colour, intended to resemble silver, are made from a mixture of four parts of copper with five of zinc. Bell-metal is an alloy of copper and tin, and in Chānda is made of four parts of copper to one part tin or tinfoil, the tin being the more expensive metal. Bells of fairly good size and excellent tone are moulded from this amalgam, and plates or saucers in which anything acid in the way of food is to be kept are also made of it, since acids do not corrode this metal as they do brass and copper. But bell-metal vessels are fragile and sometimes break when dropped. They cannot also be heated in the fire to clean them, and therefore cannot be lent to persons outside the family; while brass vessels may be lent to friends of other castes, and on being received back pollution is removed by heating them in the fire or placing hot ashes in them. Brāhmans make a small fire of grass for this purpose and pass the vessels through the flame. Copper cooking-pots are commonly used by Muhammadans but not by Hindus, as they have to be coated with tin; the Hindus consider that tin is an inferior metal whose application to copper degrades the latter. Pots made of brass with a copper rim are called ‘Ganga Jamni’ after the confluence of the dark water of the Jumna with the muddy stream of the Ganges, whose union they are supposed to symbolise. Small figures of the deities or idols are also made of brass, but some Kasārs will not attempt this work, because they are afraid of the displeasure of the god in case the figure should not be well or symmetrically shaped.

Kasbi

1. General notice

Kasbi,391 Tawāif, Devadāsi.—The caste of dancing-girls and prostitutes. The name Kasbi is derived from the Arabic kasab, prostitution, and signifies rather a profession than a caste. In India practically all female dancers and singers are prostitutes, the Hindus being still in that stage of the development of intersexual relations when it is considered impossible that a woman should perform before the public and yet retain her modesty. It is not so long that this idea has been abandoned by Western nations, and the fashion of employing women actors is perhaps not more than two or three centuries old in England. The gradual disappearance of the distinctive influence of sex in the public and social conduct of women is presumably a sign of advancing civilisation, and is greatest in the West, the old standards retaining more and more vitality as we proceed Eastward. Among the Anglo-Saxon races women are almost entirely emancipated from any handicap due to their sex, and direct their lives with the same freedom and independence as men. Among the Latin races many people still object to girls walking out alone in towns, and in Italy the number of women to be seen in the streets is so small that it must be considered improper for a young and respectable woman to go about alone. Here also survives the mariage de convenance or arrangement of matches by the parents; the underlying reason for this custom, which also partly accounts for the institution of infant-marriage, appears to be that it is not considered safe to permit a young girl to frequent the society of unmarried men with sufficient freedom to be able to make her own choice. And, finally, on arrival in Egypt and Turkey we find the seclusion of women still practised, and only now beginning to weaken before the influence of Western ideas. But again in the lowest scale of civilisation, among the Gonds and other primitive tribes, women are found to enjoy great freedom of social intercourse. This is partly no doubt because their lives are too hard and rude to permit of any seclusion of women, but also partly because they do not yet consider it an obligatory feature of the institution of marriage that a girl should enter upon it in the condition of a virgin.

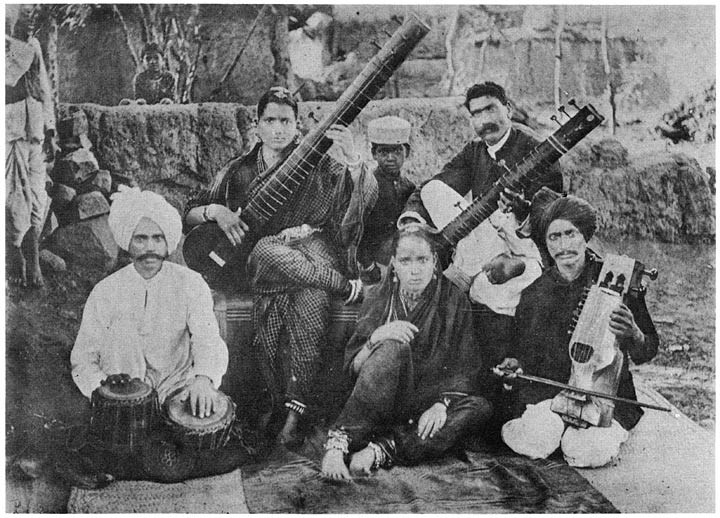

Dancing girls and musicians

2. Girls dedicated to temples

In the Deccan girls dedicated to temples are called Devadāsis or ‘Hand-maidens of the gods.’ They are thus described by Marco Polo: “In this country,” he says, “there are certain abbeys in which are gods and goddesses, and here fathers and mothers often consecrate their daughters to the service of the deity. When the priests desire to feast their god they send for those damsels, who serve the god with meats and other goods, and then sing and dance before him for about as long as a great baron would be eating his dinner. Then they say that the god has devoured the essence of the food, and fall to and eat it themselves.”2 Mr. Francis writes of the Devadāsis as follows:2 “It is one of the many inconsistences of the Hindu religion that though their profession is repeatedly and vehemently condemned by the Shāstras it has always received the countenance of the church. The rise of the caste and its euphemistic name seem both of them to date from the ninth and tenth centuries of our era, during which much activity prevailed in southern India in the matter of building temples and elaborating the services held in them. The dancing-girls’ duties then as now were to fan the idol with chamaras or Thibetan ox-tails, to hold the sacred light called Kumbarti and to sing and dance before the god when he was carried in procession. Inscriptions show that in A.D. 1004 the great temple of the Chola king Rajarāja at Tanjore had attached to it 400 women of the temple who lived in free quarters in the surrounding streets, and were given a grant of land from the endowment. Other temples had similar arrangements. At the beginning of last century there were a hundred dancing-girls attached to the temple at Conjeeveram, and at Madura, Conjeeveram and Tanjore there are still numbers of them who receive allowances from the endowments of the big temples at those places. In former days the profession was countenanced not only by the church but by the state. Abdur Razāk, a Turkish ambassador to the court of Vijayanagar in the fifteenth century, describes women of this class as living in state-controlled institutions, the revenue of which went towards the upkeep of the police.”