полная версия

полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

246. Since I wrote the earlier lectures in this volume, I have been made more doubtful on several points which were embarrassing enough before, by seeing some better (so-called) impressions of my favorite plates containing light and shade which did not improve them.

I do not choose to waste time or space in discussion, till I know more of the matter; and that more I must leave to my good friend Mr. Reid of the British Museum to find out for me; for I have no time to take up the subject myself, but I give, for frontispiece to this Appendix, the engraving of Joshua referred to in the text, which however beautiful in thought, is an example of the inferior execution and more elaborate shade which puzzle me. But whatever is said in the previous pages of the plates chosen for example, by whomsoever done, is absolutely trustworthy. Thoroughly fine they are, in their existing state, and exemplary to all persons and times. And of the rest, in fitting place I hope to give complete—or at least satisfactory account.

IIOn the three excellent engravers representative of the first, middle, and late schools

XII.

The Coronation in the Garden.

247. I have given opposite a photograph, slightly reduced from the Dürer Madonna, alluded to often in the text, as an example of his best conception of womanhood. It is very curious that Dürer, the least able of all great artists to represent womanhood, should of late have been a very principal object of feminine admiration. The last thing a woman should do is to write about art. They never see anything in pictures but what they are told, (or resolve to see out of contradiction,)—or the particular things that fall in with their own feelings. I saw a curious piece of enthusiastic writing by an Edinburgh lady, the other day, on the photographs I had taken from the tower of Giotto. She did not care a straw what Giotto had meant by them, declared she felt it her duty only to announce what they were to her; and wrote two pages on the bas-relief of Heracles and Antæus—assuming it to be the death of Abel.

248. It is not, however, by women only that Dürer has been over-praised. He stands so alone in his own field, that the people who care much for him generally lose the power of enjoying anything else rightly; and are continually attributing to the force of his imagination quaintnesses which are merely part of the general mannerism of his day.

The following notes upon him, in relation to two other excellent engravers, were written shortly for extempore expansion in lecturing. I give them, with the others in this terminal article, mainly for use to myself in future reference; but also as more or less suggestive to the reader, if he has taken up the subject seriously, and worth, therefore, a few pages of this closing sheet.

249. The men I have named as representative of all the good ones composing their school, are alike resolved their engraving shall be lovely.

But Botticelli, the ancient, wants, with as little engraving, as much Sibyl as possible.

Dürer, the central, wants, with as much engraving as possible, anything of Sibyl that may chance to be picked up with it.

Beaugrand, the modern, wants, as much Sibyl as possible, and as much engraving too.

250. I repeat—for I want to get this clear to you—Botticelli wants, with as little engraving, as much Sibyl as possible. For his head is full of Sibyls, and his heart. He can't draw them fast enough: one comes, and another and another; and all, gracious and wonderful and good, to be engraved forever, if only he had a thousand hands and lives. He scratches down one, with no haste, with no fault, divinely careful, scrupulous, patient, but with as few lines as possible. 'Another Sibyl—let me draw another, for heaven's sake, before she has burnt all her books, and vanished.'

Dürer is exactly Botticelli's opposite. He is a workman, to the heart, and will do his work magnificently. 'No matter what I do it on, so that my craft be honorably shown. Anything will do; a Sibyl, a skull, a Madonna and Christ, a hat and feather, an Adam, an Eve, a cock, a sparrow, a lion with two tails, a pig with five legs,—anything will do for me. But see if I don't show you what engraving is, be my subject what it may!'

251. Thirdly: Beaugrand, I said, wants as much Sibyl as possible, and as much engraving. He is essentially a copyist, and has no ideas of his own, but deep reverence and love for the work of others. He will give his life to represent another man's thought. He will do his best with every spot and line,—exhibit to you, if you will only look, the most exquisite completion of obedient skill; but will be content, if you will not look, to pass his neglected years in fruitful peace, and count every day well spent that has given softness to a shadow, or light to a smile.

III On Dürer's landscape, with reference to the sentence on p. 101 : "I hope you are pleased."252. I spoke just now only of the ill-shaped body of this figure of Fortune, or Pleasure. Beneath her feet is an elaborate landscape. It is all drawn out of Dürer's head;—he would look at bones or tendons carefully, or at the leaf details of foreground;—but at the breadth and loveliness of real landscape, never.

He has tried to give you a bird's-eye view of Germany; rocks, and woods, and clouds, and brooks, and the pebbles in their beds, and mills, and cottages, and fences, and what not; but it is all a feverish dream, ghastly and strange, a monotone of diseased imagination.

And here is a little bit of the world he would not look at—of the great river of his land, with a single cluster of its reeds, and two boats, and an island with a village, and the way for the eternal waters opened between the rounded hills.67

It is just what you may see any day, anywhere,—innocent, seemingly artless; but the artlessness of Turner is like the face of Gainsborough's village girl, and a joy forever.

IVOn the study of anatomy253. The virtual beginner of artistic anatomy in Italy was a man called 'The Poulterer'—from his grandfather's trade; 'Pollajuolo,' a man of immense power, but on whom the curse of the Italian mind in this age68 was set at its deepest.

Any form of passionate excess has terrific effects on body and soul, in nations as in men; and when this excess is in rage, and rage against your brother, and rage accomplished in habitual deeds of blood,—do you think Nature will forget to set the seal of her indignation upon the forehead? I told you that the great division of spirit between the northern and southern races had been reconciled in the Val d'Arno. The Font of Florence, and the Font of Pisa, were as the very springs of the life of the Christianity which had gone forth to teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Prince of Peace. Yet these two brother cities were to each other—I do not say as Abel and Cain, but as Eteocles and Polynices, and the words of Æschylus are now fulfilled in them to the uttermost. The Arno baptizes their dead bodies:—their native valley between its mountains is to them as the furrow of a grave;—"and so much of their land they have, as is sepulcher." Nay, not of Florence and Pisa only was this true: Venice and Genoa died in death-grapple; and eight cities of Lombardy divided between them the joy of leveling Milan to her lowest stone. Nay, not merely in city against city, but in street against street, and house against house, the fury of the Theban dragon flamed ceaselessly, and with the same excuse upon men's lips. The sign of the shield of Polynices, Justice bringing back the exile, was to them all, in turn, the portent of death: and their history, in the sum of it and substance, is as of the servants of Joab and Abner by the pool of Gibeon. "They caught every one his fellow by the head, and thrust his sword in his fellow's side; so they fell down together: wherefore that place was called 'the field of the strong men.'"

254. Now it is not possible for Christian men to live thus, except under a fever of insanity. I have before, in my lectures on Prudence and Insolence in art, deliberately asserted to you the logical accuracy of the term 'demoniacal possession'69—the being in the power or possession of a betraying spirit; and the definite sign of such insanity is delight in witnessing pain, usually accompanied by an instinct that gloats over or plays with physical uncleanness or disease, and always by a morbid egotism. It is not to be recognized for demoniacal power so much by its viciousness, as its paltriness,—the taking pleasure in minute, contemptible, and loathsome things.70 Now, in the middle of the gallery of the Brera at Milan, there is an elaborate study of a dead Christ, entirely characteristic of early fifteenth century Italian madman's work. It is called—and was presented to the people as—a Christ; but it is only an anatomical study of a vulgar and ghastly dead body, with the soles of the feet set straight at the spectator, and the rest foreshortened. It is either Castagno's or Mantegna's,—in my mind, set down to Castagno; but I have not looked at the picture for years, and am not sure at this moment. It does not matter a straw which: it is exactly characteristic of the madness in which all of them—Pollajuolo, Castagno, Mantegna, Lionardo da Vinci, and Michael Angelo, polluted their work with the science of the sepulcher,71 and degraded it with presumptuous and paltry technical skill. Foreshorten your Christ, and paint Him, if you can, half putrefied,—that is the scientific art of the Renaissance.

255. It is impossible, however, in so vast a subject to distinguish always the beginner of things from the establisher. To the poulterer's son, Pollajuolo, remains the eternal shame of first making insane contest the only subject of art; but the two establishers of anatomy were Lionardo and Michael Angelo. You hear of Lionardo chiefly because of his Last Supper, but Italy did not hear of him for that. This was not what brought her to worship Lionardo—but the Battle of the Standard.

VFragments on Holbein and others256. Of Holbein's St. Elizabeth, remember, she is not a perfect Saint Elizabeth, by any means. She is an honest and sweet German lady,—the best he could see; he could do no better;—and so I come back to my old story,—no man can do better than he sees: if he can reach the nature round him, it is well; he may fall short of it; he cannot rise above it; "the best, in this kind, are but shadows."

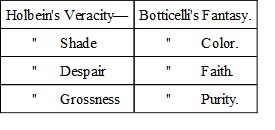

Yet that intense veracity of Holbein is indeed the strength and glory of all the northern schools. They exist only in being true. Their work among men is the definition of what is, and the abiding by it. They cannot dream of what is not. They make fools of themselves if they try. Think how feeble even Shakspere is when he tries his hand at a Goddess;—women, beautiful and womanly, as many as you choose; but who cares what his Minerva or Juno says, in the masque of the Tempest? And for the painters—when Sir Joshua tries for a Madonna, or Vandyke for a Diana—they can't even paint! they become total simpletons. Look at Rubens' mythologies in the Louvre, or at modern French heroics, or German pietisms! Why, all—Cornelius, Hesse, Overbeck, and David—put together, are not worth one De Hooghe of an old woman with a broom sweeping a back-kitchen. The one thing we northerns can do is to find out what is fact, and insist on it: mean fact it may be, or noble—but fact always, or we die.

257. Yet the intensest form of northern realization can be matched in the south, when the southerns choose. There are two pieces of animal drawing in the Sistine Chapel unrivaled for literal veracity. The sheep at the well in front of Zipporah; and afterwards, when she is going away, leading her children, her eldest boy, like every one else, has taken his chief treasure with him, and this treasure is his pet dog. It is a little sharp-nosed white fox-terrier, full of fire and life; but not strong enough for a long walk. So little Gershom, whose name was "the stranger" because his father had been a stranger in a strange land,—little Gershom carries his white terrier under his arm, lying on the top of a large bundle to make it comfortable. The doggie puts its sharp nose and bright eyes out, above his hand, with a little roguish gleam sideways in them, which means,—if I can read rightly a dog's expression,—that he has been barking at Moses all the morning and has nearly put him out of temper:—and without any doubt, I can assert to you that there is not any other such piece of animal painting in the world,—so brief, intense, vivid, and absolutely balanced in truth: as tenderly drawn as if it had been a saint, yet as humorously as Landseer's Lord Chancellor poodle.

258. Oppose to—

True Fantasy. Botticelli's Tree in Hellespontic Sibyl. Not a real tree at all—yet founded on intensest perception of beautiful reality. So the swan of Clio, as opposed to Dürer's cock, or to Turner's swan.

The Italian power of abstraction into one mythologic personage—Holbein's death is only literal. He has to split his death into thirty different deaths; and each is but a skeleton. But Orcagna's death is one—the power of death itself. There may thus be as much breadth in thought, as in execution.

259. What then, we have to ask, is a man conscious of in what he sees?

For instance, in all Cruikshank's etchings—however slight the outline—there is an intense consciousness of light and shade, and of local color, as a part of light and shade; but none of color itself. He was wholly incapable of coloring; and perhaps this very deficiency enabled him to give graphic harmony to engraving.

Bewick—snow-pieces, etc. Gray predominant; perfect sense of color, coming out in patterns of birds;—yet so uncultivated, that he engraves the brown birds better than pheasant or peacock!

For quite perfect consciousness of color makes engraving impossible, and you have instead—Correggio.

VIFinal notes on light and shade260. You will find in the 138th and 147th paragraphs of my Inaugural lectures, statements which, if you were reading the book by yourselves, would strike you probably as each of them difficult, and in some degree inconsistent,—namely, that the school of color has exquisite character and sentiment; but is childish, cheerful, and fantastic; while the school of shade is deficient in character and sentiment; but supreme in intellect and veracity. "The way by light and shade," I say, "is taken by men of the highest powers of thought and most earnest desire for truth."

The school of shade, I say, is deficient in character and sentiment. Compare any of Dürer's Madonnas with any of Angelico's.

Yet you may discern in the Apocalypse engravings that Dürer's mind was seeking for truths, and dealing with questions, which no more could have occurred to Angelico's mind than to that of a two-years-old baby.

261. The two schools unite in various degrees; but are always distinguishably generic, the two headmost masters representing each being Tintoret and Perugino. The one, deficient in sentiment, and continually offending us by the want of it, but full of intellectual power and suggestion.

The other, repeating ideas with so little reflection that he gets blamed for doing the same thing over again, (Vasari); but exquisite in sentiment and the conditions of taste which it forms, so as to become the master of it to Raphael and to all succeeding him; and remaining such a type of sentiment, too delicate to be felt by the latter practical mind of Dutch-bred England, that Goldsmith makes the admiration of him the test of absurd connoisseurship. But yet, with under-current of intellect, which gets him accused of free-thinking, and therefore with under-current of entirely exquisite chiaroscuro.

Light and shade, then, imply the understanding of things—Color, the imagination and the sentiment of them.

262. In Turner's distinctive work, color is scarcely acknowledged unless under influence of sunshine. The sunshine is his treasure; his lividest gloom contains it; his grayest twilight regrets it, and remembers. Blue is always a blue shadow; brown or gold, always light;—nothing is cheerful but sunshine; wherever the sun is not, there is melancholy or evil. Apollo is God; and all forms of death and sorrow exist in opposition to him.

But in Perugino's distinctive work,—and therefore I have given him the captain's place over all,—there is simply no darkness, no wrong. Every color is lovely, and every space is light. The world, the universe, is divine: all sadness is a part of harmony; and all gloom, a part of peace.

THE END1

"Inaugural Series," "Aratra Pentelici," and "Eagle's Nest."

2

My inaugural series of seven lectures (now published uniform in size with this edition. 1890).

3

Compare Inaugural Lectures, § 144.

4

Compare "Aratra Pentelici," § 154.

5

"Holbein and His Time," 4to, Bentley, 1872, (a very valuable book,) p. 17. Italics mine.

6

See Carlyle, "Frederick," Book III., chap. viii.

7

I believe I am taking too much trouble in writing these lectures. This sentence, § 44, has cost me, I suppose, first and last, about as many hours as there are lines in it;—and my choice of these two words, faith and death, as representatives of power, will perhaps, after all, only puzzle the reader.

8

He is said by Vasari to have called Francia the like. Francia is a child compared to Perugino; but a finished working-goldsmith and ornamental painter nevertheless; and one of the very last men to be called 'goffo,' except by unparalleled insolence.

9

The diagram used at the lecture is engraved on page 30; the reader had better draw it larger for himself, as it had to be made inconveniently small for this size of leaf.

10

'Ascertained,' scarcely any date ever is, quite satisfactorily. The diagram only represents what is practically and broadly true. I may have to modify it greatly in detail.

11

For fust, log of wood, erroneously 'fer' in the later printed editions. Compare the account of the works of Art and Nature, towards the end of the Romance of the Rose.

12

Of course it would have been impossible to express in any accurate terms, short enough for the compass of a lecture, the conditions of opposition between the Heptarchy and the Northmen;—between the Byzantine and Roman;—and between the Byzantine and Arab, which form minor, but not less trenchant, divisions of Art-province, for subsequent delineation. If you can refer to my "Stones of Venice," see § 20 of its first chapter.

13

Again much too broad a statement: not to be qualified but by a length of explanation here impossible. My lectures on Architecture, now in preparation ("Val d'Arno"), will contain further detail.

14

At the side of my page, here, I find the following memorandum, which was expanded in the viva-voce lecture. The reader must make what he can of it, for I can't expand it here.

Sense of Italian Church plan.

Baptistery, to make Christians in; house, or dome, for them to pray and be preached to in; bell-tower, to ring all over the town, when they were either to pray together, rejoice together, or to be warned of danger.

Harvey's picture of the Covenanters, with a shepherd on the outlook, as a campanile.

15

And 'chassis,' a window frame, or tracery.

16

This present lecture does not, as at present published, justify its title; because I have not thought it necessary to write the viva-voce portions of it which amplified the 69th paragraph. I will give the substance of them in better form elsewhere; meantime the part of the lecture here given may be in its own way useful.

17

By Mr. Burgess. The toil and skill necessary to produce a facsimile of this degree of precision will only be recognized by the reader who has had considerable experience of actual work.

18

The ordinary title-page of Punch.

19

In the lecture-room, the relative rates of execution were shown; I arrive at this estimate by timing the completion of two small pieces of shade in the two methods.

20

John Bull, as Sir Oliver Surface, with Sir Peter Teazle and Joseph Surface. It appeared in Punch, early in 1863.

21

In preparing these passages for the press, I feel perpetual need of qualifications and limitations, for it is impossible to surpass the humor, or precision of expressional touch, in the really golden parts of Tenniel's works; and they may be immortal, as representing what is best in their day.

22

From Bewick's Æsop's Fables.

23

See ante, § 43.

24

This paragraph was not read at the lecture, time not allowing:—it is part of what I wrote on engraving some years ago, in the papers for the Art Journal, called the Cestus of Aglaia. (Refer now to "On the Old Road.")

25

An effort has lately been made in France, by Meissonier, Gérome, and their school, to recover it, with marvelous collateral skill of engravers. The etching of Gérome's Louis XIV. and Molière is one of the completest pieces of skillful mechanism ever put on metal.

26

I must again qualify the too sweeping statement of the text. I think, as time passes, some of these nineteenth century line engravings will become monumental. The first vignette of the garden, with the cut hedges and fountain, for instance, in Rogers' poems, is so consummate in its use of every possible artifice of delicate line, (note the look of tremulous atmosphere got by the undulatory etched lines on the pavement, and the broken masses, worked with dots, of the fountain foam,) that I think it cannot but, with some of its companions, survive the refuse of its school, and become classic. I find in like manner, even with all their faults and weaknesses, the vignettes to Heyne's Virgil to be real art-possessions.

27

Plate XI., in the Appendix, taken from the engraving of the Virgin sitting in the fenced garden, with two angels crowning her.

28

The method was first developed in engraving designs on silver—numbers of lines being executed with dots by the punch, for variety's sake. For niello, and printing, a transverse cut was substituted for the blow. The entire style is connected with the later Roman and Byzantine method of drawing lines with the drill hole, in marble. See above, Lecture II., Section 70.

29

This most important and distinctive character was pointed out to me by Mr. Burgess.

30

This point will be further examined and explained in the Appendix.

31

See Appendix, Article I.

32

If you paint a bottle only to amuse the spectator by showing him how like a painting may be to a bottle, you cannot be considered, in art-philosophy, as a designer. But if you paint the cork flying out of the bottle, and the contents arriving in an arch at the mouth of a recipient glass, you are so far forth a designer or signer; probably meaning to express certain ultimate facts respecting, say, the hospitable disposition of the landlord of the house; but at all events representing the bottle and glass in a designed, and not merely natural, manner. Not merely natural—nay, in some sense non-natural, or supernatural. And all great artists show both this fantastic condition of mind in their work, and show that it has arisen out of a communicative or didactic purpose. They are the Signpainters of God.