полная версия

полная версияAriadne Florentina: Six Lectures on Wood and Metal Engraving

Now I had got this line out of the tablet in the engraving of Raphael's vision, and had forgotten where it came from. And I thought I knew my sixth book of Virgil so well, that I never looked at it again while I was giving these lectures at Oxford, and it was only here at Assisi, the other day, wanting to look more accurately at the first scene by the lake Avernus, that I found I had been saved by the words of the Cumaean Sibyl.

215. "Quam tua te Fortuna sinet," the completion of the sentence, has yet more and continual teaching in it for me now; as it has for all men. Her opening words, which have become hackneyed, and lost all present power through vulgar use of them, contain yet one of the most immortal truths ever yet spoken for mankind; and they will never lose their power of help for noble persons. But observe, both in that lesson, "Facilis descensus Averni," etc.; and in the still more precious, because universal, one on which the strength of Rome was founded,—the burning of the books,—the Sibyl speaks only as the voice of Nature, and of her laws;—not as a divine helper, prevailing over death; but as a mortal teacher warning us against it, and strengthening us for our mortal time; but not for eternity. Of which lesson her own history is a part, and her habitation by the Avernus lake. She desires immortality, fondly and vainly, as we do ourselves. She receives, from the love of her refused lover, Apollo, not immortality, but length of life;—her years to be as the grains of dust in her hand. And even this she finds was a false desire; and her wise and holy desire at last is—to die. She wastes away; becomes a shade only, and a voice. The Nations ask her, What wouldst thou? She answers, Peace; only let my last words be true. "L'ultimo mie parlar sie verace."

VII.

For a time, and times.

216. Therefore, if anything is to be conceived, rightly, and chiefly, in the form of the Cumaean Sibyl, it must be of fading virginal beauty, of enduring patience, of far-looking into futurity. "For after my death there shall yet return," she says, "another virgin."

Jam redit et virgo;—redeunt Saturnia regna,Ultima Cumaei venit jam carminis aetas.Here then is Botticelli's Cumaean Sibyl. She is armed, for she is the prophetess of Roman fortitude;—but her faded breast scarcely raises the corselet; her hair floats, not falls, in waves like the currents of a river,—the sign of enduring life; the light is full on her forehead: she looks into the distance as in a dream. It is impossible for art to gather together more beautifully or intensely every image which can express her true power, or lead us to understand her lesson.

VIII.

The Nymph beloved of Apollo.

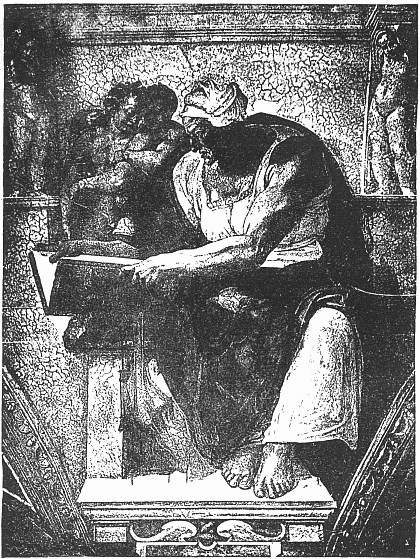

(MICHAEL ANGELO.)

217. Now you do not, I am well assured, know one of Michael Angelo's sibyls from another: unless perhaps the Delphian, whom of course he makes as beautiful as he can. But of this especially Italian prophetess, one would have thought he might, at least in some way, have shown that he knew the history, even if he did not understand it. She might have had more than one book, at all events, to burn. She might have had a stray leaf or two fallen at her feet. He could not indeed have painted her only as a voice; but his anatomical knowledge need not have hindered him from painting her virginal youth, or her wasting and watching age, or her inspired hope of a holier future.

218. Opposite,—fortunately, photograph from the figure itself, so that you can suspect me of no exaggeration,—is Michael Angelo's Cumaean Sibyl, wasting away. It is by a grotesque and most strange chance that he should have made the figure of this Sibyl, of all others in the chapel, the most fleshly and gross, even proceeding to the monstrous license of showing the nipples of the breast as if the dress were molded over them like plaster. Thus he paints the poor nymph beloved of Apollo,—the clearest and queenliest in prophecy and command of all the sibyls,—as an ugly crone, with the arms of Goliath, poring down upon a single book.

219. There is one point of fine detail, however, in Botticelli's Cumaean Sibyl, and in the next I am going to show you, to explain which I must go back for a little while to the question of the direct relation of the Italian painters to the Greek. I don't like repeating in one lecture what I have said in another; but to save you the trouble of reference, must remind you of what I stated in my fourth lecture on Greek birds, when we were examining the adoption of the plume crests in armor, that the crest signifies command; but the diadem, obedience; and that every crown is primarily a diadem. It is the thing that binds, before it is the thing that honors.

Now all the great schools dwell on this symbolism. The long flowing hair is the symbol of life, and the διάδημα of the law restraining it. Royalty, or kingliness, over life, restraining and glorifying. In the extremity of restraint—in death, whether noble, as of death to Earth, or ignoble, as of death to Heaven, the διάδημα is fastened with the mort-cloth: "Bound hand and foot with grave-clothes, and the face bound about with the napkin."

220. Now look back to the first Greek head I ever showed you, used as the type of archaic sculpture in Aratra Pentelici, and then look at the crown in Botticelli's Astrologia. It is absolutely the Greek form,—even to the peculiar oval of the forehead; while the diadem—the governing law—is set with appointed stars—to rule the destiny and thought. Then return to the Cumaean Sibyl. She, as we have seen, is the symbol of enduring life—almost immortal. The diadem is withdrawn from the forehead—reduced to a narrow fillet—here, and the hair thrown free.

IX.

In the woods of Ida.

221. From the Cumaean Sibyl's diadem, traced only by points, turn to that of the Hellespontic, (Plate 9, opposite). I do not know why Botticelli chose her for the spirit of prophecy in old age; but he has made this the most interesting plate of the series in the definiteness of its connection with the work from Dante, which becomes his own prophecy in old age. The fantastic yet solemn treatment of the gnarled wood occurs, as far as I know, in no other engravings but this, and the illustrations to Dante; and I am content to leave it, with little comment, for the reader's quiet study, as showing the exuberance of imagination which other men at this time in Italy allowed to waste itself in idle arabesque, restrained by Botticelli to his most earnest purposes; and giving the withered tree-trunks, hewn for the rude throne of the aged prophetess, the same harmony with her fading spirit which the rose has with youth, or the laurel with victory. Also in its weird characters, you have the best example I can show you of the orders of decorative design which are especially expressible by engraving, and which belong to a group of art instincts scarcely now to be understood, much less recovered, (the influence of modern naturalistic imitation being too strong to be conquered)—the instincts, namely, for the arrangement of pure line, in labyrinthine intricacy, through which the grace of order may give continual clue. The entire body of ornamental design, connected with writing, in the Middle Ages seems as if it were a sensible symbol, to the eye and brain, of the methods of error and recovery, the minglings of crooked with straight, and perverse with progressive, which constitute the great problem of human morals and fate; and when I chose the title for the collected series of these lectures, I hoped to have justified it by careful analysis of the methods of labyrinthine ornament, which, made sacred by Theseian traditions,54 and beginning, in imitation of physical truth, with the spiral waves of the waters of Babylon as the Assyrian carved them, entangled in their returns the eyes of men, on Greek vase and Christian manuscript—till they closed in the arabesques which sprang round the last luxury of Venice and Rome.

But the labyrinth of life itself, and its more and more interwoven occupation, become too manifold, and too difficult for me; and of the time wasted in the blind lanes of it, perhaps that spent in analysis or recommendation of the art to which men's present conduct makes them insensible, has been chiefly cast away. On the walls of the little room where I finally revise this lecture,55 hangs an old silken sampler of great-grandame's work: representing the domestic life of Abraham: chiefly the stories of Isaac and Ishmael. Sarah at her tent-door, watching, with folded arms, the dismissal of Hagar: above, in a wilderness full of fruit trees, birds, and butterflies, little Ishmael lying at the root of a tree, and the spent bottle under another; Hagar in prayer, and the angel appearing to her out of a wreathed line of gloomily undulating clouds, which, with a dark-rayed sun in the midst, surmount the entire composition in two arches, out of which descend shafts of (I suppose) beneficent rain; leaving, however, room, in the corner opposite to Ishmael's angel, for Isaac's, who stays Abraham in the sacrifice; the ram in the thicket, the squirrel in the plum tree above him, and the grapes, pears, apples, roses, and daisies of the foreground, being all wrought with involution of such ingenious needlework as may well rank, in the patience, the natural skill, and the innocent pleasure of it, with the truest works of Florentine engraving. Nay; the actual tradition of many of the forms of ancient art is in many places evident,—as, for instance, in the spiral summits of the flames of the wood on the altar, which are like a group of first-springing fern. On the wall opposite is a smaller composition, representing Justice with her balance and sword, standing between the sun and moon, with a background of pinks, borage, and corn-cockle: a third is only a cluster of tulips and iris, with two Byzantine peacocks; but the spirits of Penelope and Ariadne reign vivid in all the work—and the richness of pleasurable fancy is as great still, in these silken labors, as in the marble arches and golden roof of the cathedral of Monreale.

But what is the use of explaining or analyzing it? Such work as this means the patience and simplicity of all feminine life; and can be produced, among us at least, no more. Gothic tracery itself, another of the instinctive labyrinthine intricacies of old, though analyzed to its last section, has become now the symbol only of a foolish ecclesiastical sect, retained for their shibboleth, joyless and powerless for all good. The very labyrinth of the grass and flowers of our fields, though dissected to its last leaf, is yet bitten bare, or trampled to slime, by the Minotaur of our lust; and for the traceried spire of the poplar by the brook, we possess but the four-square furnace tower, to mingle its smoke with heaven's thunder-clouds.56

We will look yet at one sampler more of the engraved work, done in the happy time when flowers were pure, youth simple, and imagination gay,—Botticelli's Libyan Sibyl.

Glance back first to the Hellespontic, noting the close fillet, and the cloth bound below the face, and then you will be prepared to understand the last I shall show you, and the loveliest of the southern Pythonesses.

X.

Grass of the Desert.

222. A less deep thinker than Botticelli would have made her parched with thirst, and burnt with heat. But the voice of God, through nature, to the Arab or the Moor, is not in the thirst, but in the fountain—not in the desert, but in the grass of it. And this Libyan Sibyl is the spirit of wild grass and flowers, springing in desolate places.

You see, her diadem is a wreath of them; but the blossoms of it are not fastening enough for her hair, though it is not long yet—(she is only in reality a Florentine girl of fourteen or fifteen)—so the little darling knots it under her ears, and then makes herself a necklace of it. But though flowing hair and flowers are wild and pretty, Botticelli had not, in these only, got the power of Spring marked to his mind. Any girl might wear flowers; but few, for ornament, would be likely to wear grass. So the Sibyl shall have grass in her diadem; not merely interwoven and bending, but springing and strong. You thought it ugly and grotesque at first, did not you? It was made so, because precisely what Botticelli wanted you to look at.

But that's not all. This conical cap of hers, with one bead at the top,—considering how fond the Florentines are of graceful head-dresses, this seems a strange one for a young girl. But, exactly as I know the angel of Victory to be Greek, at his Mount of Pity, so I know this head-dress to be taken from a Greek coin, and to be meant for a Greek symbol. It is the Petasus of Hermes—the mist of morning over the dew. Lastly, what will the Libyan Sibyl say to you? The letters are large on her tablet. Her message is the oracle from the temple of the Dew: "The dew of thy birth is as the womb of the morning."—"Ecce venientem diem, et latentia aperientem, tenebit gremio gentium regina."

223. Why the daybreak came not then, nor yet has come, but only a deeper darkness; and why there is now neither queen nor king of nations, but every man doing that which is right in his own eyes, I would fain go on, partly to tell you, and partly to meditate with you: but it is not our work for to-day. The issue of the Reformation which these great painters, the scholars of Dante, began, we may follow, farther, in the study to which I propose to lead you, of the lives of Cimabue and Giotto, and the relation of their work at Assisi to the chapel and chambers of the Vatican.

224. To-day let me finish what I have to tell you of the style of southern engraving. What sudden bathos in the sentence, you think! So contemptible the question of style, then, in painting, though not in literature? You study the 'style' of Homer; the style, perhaps, of Isaiah; the style of Horace, and of Massillon. Is it so vain to study the style of Botticelli?

In all cases, it is equally vain, if you think of their style first. But know their purpose, and then, their way of speaking is worth thinking of. These apparently unfinished and certainly unfilled outlines of the Florentine,—clumsy work, as Vasari thought them,—as Mr. Otley and most of our English amateurs still think them,—are these good or bad engraving?

You may ask now, comprehending their motive, with some hope of answering or being answered rightly. And the answer is, They are the finest gravers' work ever done yet by human hand. You may teach, by process of discipline and of years, any youth of good artistic capacity to engrave a plate in the modern manner; but only the noblest passion, and the tenderest patience, will ever engrave one line like these of Sandro Botticelli.

225. Passion, and patience! Nay, even these you may have to-day in England, and yet both be in vain. Only a few years ago, in one of our northern iron-foundries, a workman of intense power and natural art-faculty set himself to learn engraving;—made his own tools; gave all the spare hours of his laborious life to learn their use; learnt it; and engraved a plate which, in manipulation, no professional engraver would be ashamed of. He engraved his blast furnace, and the casting of a beam of a steam engine. This, to him, was the power of God,—it was his life. No greater earnestness was ever given by man to promulgate a Gospel. Nevertheless, the engraving is absolutely worthless. The blast furnace is not the power of God; and the life of the strong spirit was as much consumed in the flames of it, as ever driven slave's by the burden and heat of the day.

How cruel to say so, if he yet lives, you think! No, my friends; the cruelty will be in you, and the guilt, if, having been brought here to learn that God is your Light, you yet leave the blast furnace to be the only light of England.

226. It has been, as I said in the note above (§ 200), with extreme pain that I have hitherto limited my notice of our own great engraver and moralist, to the points in which the disadvantages of English art-teaching made him inferior to his trained Florentine rival. But, that these disadvantages were powerless to arrest or ignobly depress him;—that however failing in grace and scholarship, he should never fail in truth or vitality; and that the precision of his unerring hand57—his inevitable eye—and his rightly judging heart—should place him in the first rank of the great artists not of England only, but of all the world and of all time:—that this was possible to him, was simply because he lived a country life. Bewick himself, Botticelli himself, Apelles himself, and twenty times Apelles, condemned to slavery in the hell-fire of the iron furnace, could have done—Nothing. Absolute paralysis of all high human faculty must result from labor near fire. The poor engraver of the piston-rod had faculties—not like Bewick's, for if he had had those, he never would have endured the degradation; but assuredly, (I know this by his work,) faculties high enough to have made him one of the most accomplished figure painters of his age. And they are scorched out of him, as the sap from the grass in the oven: while on his Northumberland hill-sides, Bewick grew into as stately life as their strongest pine.

227. And therefore, in words of his, telling consummate and unchanging truth concerning the life, honor, and happiness of England, and bearing directly on the points of difference between class and class which I have not dwelt on without need, I will bring these lectures to a close.

"I have always, through life, been of opinion that there is no business of any kind that can be compared to that of a man who farms his own land. It appears to me that every earthly pleasure, with health, is within his reach. But numbers of these men (the old statesmen) were grossly ignorant, and in exact proportion to that ignorance they were sure to be offensively proud. This led them to attempt appearing above their station, which hastened them on to their ruin; but, indeed, this disposition and this kind of conduct invariably leads to such results. There were many of these lairds on Tyneside; as well as many who held their lands on the tenure of 'suit and service,' and were nearly on the same level as the lairds. Some of the latter lost their lands (not fairly, I think) in a way they could not help; many of the former, by their misdirected pride and folly, were driven into towns, to slide away into nothingness, and to sink into oblivion, while their 'ha' houses' (halls), that ought to have remained in their families from generation to generation, have moldered away. I have always felt extremely grieved to see the ancient mansions of many of the country gentlemen, from somewhat similar causes, meet with a similar fate. The gentry should, in an especial manner, prove by their conduct that they are guarded against showing any symptom of foolish pride; at the same time that they soar above every meanness, and that their conduct is guided by truth, integrity, and patriotism. If they wish the people to partake with them in these good qualities, they must set them the example, without which no real respect can ever be paid to them. Gentlemen ought never to forget the respectable station they hold in society, and that they are the natural guardians of public morals and may with propriety be considered as the head and the heart of the country, while 'a bold peasantry' are, in truth, the arms, the sinews, and the strength of the same; but when these last are degraded, they soon become dispirited and mean, and often dishonest and useless."

"This singular and worthy man58 was perhaps the most invaluable acquaintance and friend I ever met with. His moral lectures and advice to me formed a most important succedaneum to those imparted by my parents. His wise remarks, his detestation of vice, his industry, and his temperance, crowned with a most lively and cheerful disposition, altogether made him appear to me as one of the best of characters. In his workshop I often spent my winter evenings. This was also the case with a number of young men who might be considered as his pupils; many of whom, I have no doubt, he directed into the paths of truth and integrity, and who revered his memory through life. He rose early to work, lay down when he felt weary, and rose again when refreshed. His diet was of the simplest kind; and he ate when hungry, and drank when dry, without paying regard to meal-times. By steadily pursuing this mode of life he was enabled to accumulate sums of money—from ten to thirty pounds. This enabled him to get books, of an entertaining and moral tendency, printed and circulated at a cheap rate. His great object was, by every possible means, to promote honorable feelings in the minds of youth, and to prepare them for becoming good members of society. I have often discovered that he did not overlook ingenious mechanics, whose misfortunes—perhaps mismanagement—had led them to a lodging in Newgate. To these he directed his compassionate eye, and for the deserving (in his estimation), he paid their debt, and set them at liberty. He felt hurt at seeing the hands of an ingenious man tied up in prison, where they were of no use either to himself or to the community. This worthy man had been educated for a priest; but he would say to me, 'Of a "trouth," Thomas, I did not like their ways.' So he gave up the thoughts of being a priest, and bent his way from Aberdeen to Edinburgh, where he engaged himself to Allan Ramsay, the poet, then a bookseller at the latter place, in whose service he was both shopman and bookbinder. From Edinburgh he came to Newcastle. Gilbert had had a liberal education bestowed upon him. He had read a great deal, and had reflected upon what he had read. This, with his retentive memory, enabled him to be a pleasant and communicative companion. I lived in habits of intimacy with him to the end of his life; and, when he died, I, with others of his friends, attended his remains to the grave at the Ballast Hills."

And what graving on the sacred cliffs of Egypt ever honored them, as that grass-dimmed furrow does the mounds of our Northern land?

NOTES

228. I. The following letter, from one of my most faithful readers, corrects an important piece of misinterpretation in the text. The waving of the reins must be only in sign of the fluctuation of heat round the Sun's own chariot:—

"Spring Field, Ambleside, "February 11, 1875."Dear Mr. Ruskin,—Your fifth lecture on Engraving I have to hand.

"Sandro intended those wavy lines meeting under the Sun's right59 hand, (Plate V.) primarily, no doubt, to represent the four ends of the four reins dangling from the Sun's hand. The flames and rays are seen to continue to radiate from the platform of the chariot between and beyond these ends of the reins, and over the knee. He may have wanted to acknowledge that the warmth of the earth was Apollo's, by making these ends of the reins spread out separately and wave, and thereby inclose a form like a flame. But I cannot think it.

"Believe me,"Ever yours truly,"Chas. Wm. Smith."II. I meant to keep labyrinthine matters for my Appendix; but the following most useful by-words from Mr. Tyrwhitt had better be read at once:—

"In the matter of Cretan Labyrinth, as connected by Virgil with the Ludus Trojæ, or equestrian game of winding and turning, continued in England from twelfth century; and having for last relic the maze60 called 'Troy Town,' at Troy Farm, near Somerton, Oxfordshire, which itself resembles the circular labyrinth on a coin of Cnossus in Fors Clavigera. (Letter 23, p. 12.)

"The connecting quotation from Virg., Æn., V. 588, is as follows:

'Ut quondam Creta fertur Labyrinthus in altaParietibus textum cæcis iter, ancipitemqueMille viis habuisse dolum, qua signa sequendiFalleret indeprensus et inremeabilis error.Haud alio Teucrün nati vestigia cursuImpediunt, texuntque fagas et prœlia ludo,Delphinum similes.'"Labyrinth of Ariadne, as cut on the Downs by shepherds from time immemorial,—

Shakespeare, 'Midsummer Night's Dream,' Act ii., sc. 2:

"Oberon. The nine-men's morris61 is filled up with mud;And the quaint mazes in the wanton greenBy lack of tread are undistinguishable."The following passage, 'Merchant of Venice,' Act iii., sc. 2, confuses (to all appearance) the Athenian tribute to Crete, with the story of Hesione: and may point to general confusion in the Elizabethan mind about the myths: