полная версия

полная версия"Wee Tim'rous Beasties": Studies of Animal life and Character

“That is all very well,” said I; “but it seems to me that there ought to be room for both of you.”

“Well, there isn’t,” said he, “and Nature has worked it out that there shan’t be, and if you write a thousand letters to the Field, you won’t alter that.”

“Suppose the martins got the pull over the sparrows, do you think it would be better for things in general?”

“You mean better for yourself,” said the sparrow, sharply.

On reflection, I came to the conclusion that that was just what I did mean.

“I don’t believe an increase of insect-eating birds would do you much good,” he went on. “Suppose, for instance, the ichneumon flies were decimated, what a time it would be for the caterpillars! How would some of your plants get on if there weren’t enough insects to fertilize them?”

I felt it was time to shift my ground. “Let us get back to your early history,” said I. “What was the nest like?”

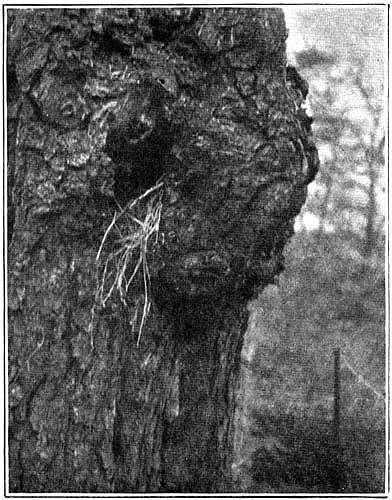

“It was in a hole of a tree-stump,” said he. “A silly sort of place, I think, not ten feet from the ground. Now I always build as high as I can—just underneath the rooks’-nests, in fact. You’re safe from boys; they don’t shoot your nest to bits for fear of shooting the rooks’-nests too; and there’s abundance of insect food on the spot. The nest itself was mostly feathery stuff, though I remember a piece of pink paper, which used to tickle me. I suppose the colour of it took the old birds’ fancy. Of course the nest was distinct from the casing. That was the usual straw. I think it is the casing of sparrows’-nests that you humans object to as untidy.”

“We chiefly object to the portion which stops up the water-pipes,” said I. “What did you have to eat?”

“Insects, I expect, to start with. At least, that is what I always give my youngsters; then, as my gizzard strengthened, small, hard seeds; then bigger ones; finally, corn itself. That is my favourite diet at the present time. Three parts of what I eat is corn, the rest is insects, seeds, and scraps.”

IT WAS IN A HOLE OF A TREE-STUMP.

“You can get corn all the year round?”

“Oh! easily enough. In the fields, when it is growing; round the wheat-stacks later, or among the poultry—people don’t shoot into the middle of the poultry—anywhere, in fact.”

“And you really like corn better than anything?”

“There is nothing quite so nice in the world,” said the sparrow, “as fresh, young corn in the ear, which you can just squeeze the juice out of and then drop.”

“And are you aware of the amount of damage which you do to the poor, struggling farmer?” said I, assuming a judicial severity which I was far from feeling.

The flippancy was infectious.

“A recent estimate places it at £770,094 per annum,” said the sparrow. “Just think of that!”

“In this country alone,” said I. “You seem to forget America, Australia, South Africa, and all the other places to which you have been unhappily introduced as an insecticide.”

“You seem to forget,” he retorted, “that it was you yourselves who made the introduction. You tried to improve on the natural balance which was ordained for this string of countries, and a pretty mess you have made of it. Now you want to crown your folly of introducing the sparrow where Nature said it was not wanted, by exterminating it where Nature says it is wanted—and that’s here.”

“I don’t think any one has suggested that you should be exterminated,” said I.

“‘To lessen their numbers in our country, every possible means must be had recourse to.’ There’s a pretty piece of grammar for you.”

He was obviously quoting again.

“You couldn’t exterminate me if you tried, and, therefore, you very properly don’t suggest it. I have been called the Avian Rat, and I am the Avian Rat. You can no more get rid of me than you can of my four-footed counterpart. It would be a bad day for you if you could.”

“But you must admit that both you and the rat are increasing in numbers, and, therefore, in destructiveness. What is to be the end of it?”

“The end of it will be that you will preserve our enemies instead of shooting them at sight.”

“Meaning?”

“Hawks, owls, weasels, and so on.”

“But hawks would never come near the towns?”

“We aren’t in town the whole year round. Even the cockneyest of sparrows has his month or two in the cornfields. I don’t mind telling you that one of the reasons we have for clinging to human habitations is that we are thus sure of sanctuary. Our natural enemies will always be welcomed with a gun. They know that, too, and keep away. Make it an offence to kill a bird or beast of prey, and you will see a difference in the rats and sparrows.”

“What about the pheasants?” said I.

“There would be fewer pheasants,” said the sparrow; “and, if you only knew it, they would taste better, if there were.”

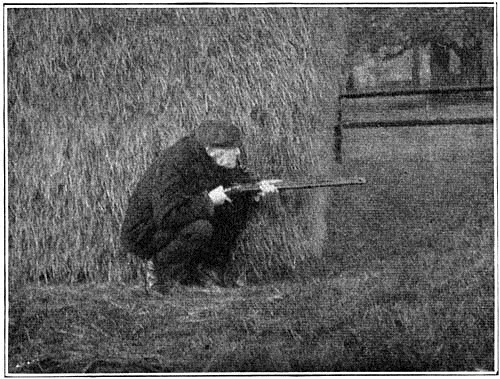

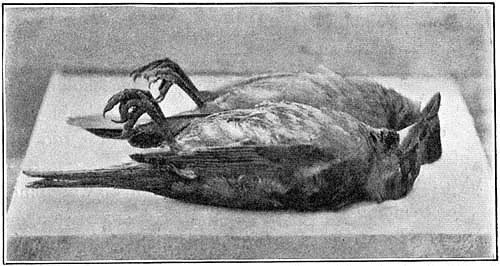

YOU HAVE BEEN SHOT AT.

“Sparrow,” said I, “to speak disrespectfully of the battue places you at once outside the pale. You are an Avian Rat. You do consume an inordinate quantity of corn. Since history began you have been an impudent parasite on man. As a hieroglyphic character you signified the enemy. Choleric old gentlemen have been roused to frenzy over your misdeeds. You have been shot at, trapped, poisoned, netted. Like the chafers, you have been excommunicated. You have been made into a yearly tribute, by the thousand. Laws have been enacted to compass your destruction, letters have been written to the Field, and yet—and yet—an inscrutable Providence has decreed that you shall survive, increase, and multiply. What good do you do?”

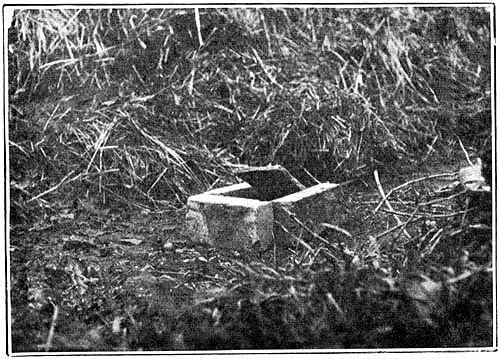

TRAPPED.

“Have you ever heard me sing?” said the sparrow.

“Sing!” I cried; “that sempiternal twitter, that intolerable chirrup that destroys the best and latest hours of sleep! Do you call that singing?”

“What bird would you prefer?” he blandly inquired.

I considered for a moment. The grim possibility of ten thousand nightingales yodelling in chorus, of ten thousand skylarks, or of ten thousand cuckoos, determined my answer.

“I cannot think of one,” said I. “But this is no merit on your part, it is merely a qualification of evil.”

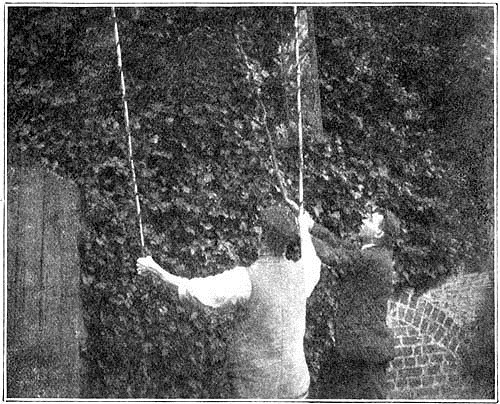

NETTED.

“I thought you would acknowledge that,” said the sparrow. "But, seriously, you ask me what good I do, and I will tell you. That my infant food consisted entirely of insects and caterpillars you already know. Turn the statistician to work who has so cunningly reduced my corn-depredations to pounds, shillings, and pence, and he will assuredly find that the insects devoured by the infant sparrow population in a year will amount to hundreds of millions. These, mind you, are insects large enough to be brought to us in our parent’s beaks.

AVIAN RAT, INDEED! RATHER AVIAN SCAVENGER!

“But what of the insect eggs devoured by us in winter, when most of your pretty insect-eating birds have flown to where the insect is commoner, fatter, and fuller-flavoured? It is we stay-at-home British birds that really keep the insects down. I know that insect eggs do not appear in our poor dissected gizzards. How should they? How would you recognize their remains, O sapient sparrow-shooters? But they are there, for all that. Those blessed with eyes can see us hunting for them in the fallen leaves, among the garbage, in the crannies of the very pavement.

I FELT ASHAMED.

“What, again, of weed seeds in general, and knotgrass in particular? Avian Rat, indeed! rather Avian Scavenger, who draws his hard-earned pay in corn. Can you grudge him a few paltry millions? Would you exterminate him because in your blindness you only note the debit side? There is a Power behind the sparrow. It is Nature herself, and against Her fixed resolve nothing avails.”

He had worked himself into an incoherent frenzy; but, even as he relapsed from this fierce air of consequence to his vulgarian self, I felt ashamed.

THE AWAKENING OF THE DORMOUSE

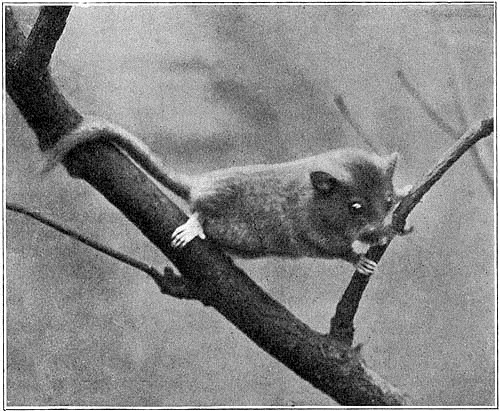

He lay face downwards—two tiny fists tight-clenched against his cheeks, his feet curled up to meet them, his tail swung gracefully across his eyes.

Nine weeks had he lain thus, self-entombed. Within the hollow of the old hazel-stump he had fashioned a rough sphere of honeysuckle bark; within this, again, a nest of feathery grass stems. He had put the roof on last of all.

A winter sunbeam pierced the screen of woodbine, and, for a moment, shed the warmth of springtime on the nest. His whiskers gave a feeble flicker in response. Next day the treacherous radiance lingered. He unclenched one fist, and wound four tiny fingers round a grass-stem. On the fourth day he half-opened his eyes (even half-opened they were beautiful), and sat up, dazed and blinking. The sunbeam had reached his heart.

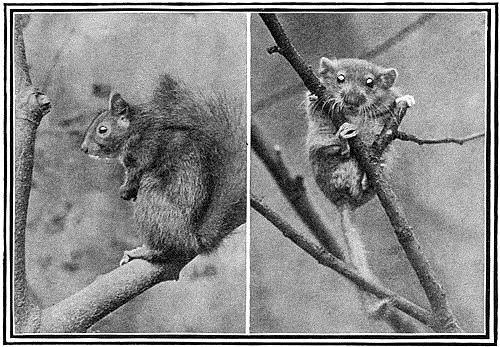

“WHAT, AWAKE?” SHOUTED THE SQUIRREL.

Yet it was a full hour before he was conscious that he lived. At first he felt nothing but a dull quickening throb within his body. His feet and hands were ice-cold, and he swayed from side to side, feeling for his strength. Then came the pricking of ten thousand tiny needles in his limbs. His heart beat as though it would burst its prison. His whole frame quivered. His bristles stood stiff-pointed from their roots. As the heart-throb slowed, his muscles slackened and obeyed his will, but yet he felt that something was amiss. Before him danced a yellow quivering haze, his feet were heavy and awkward, his chest ached as he breathed, and he was cold, oh, so cold! It was no easy matter to reach the nest-top. He climbed mechanically upwards, digging his toes into the meshwork of the sides, and sobbing from sheer weakness as he climbed.

He made a small parting in the roof, and peeped out. It was only for a moment, for he fell back stunned and blinded by the glare. Still, in that moment, he had caught a glimpse of an unfamiliar world, leafless, lifeless, silent, miserable. He tucked his nose between his four paws, swung his tail across his eyes, and waited patiently for the darkness. With the darkness came the cold. It stole upon him gently, quelled the heart-throb, reclenched the tiny fists, and lulled him to forget.

It was better the next time. The old hazel was making coquettish efforts to renew its youth. It had hung its last remaining shoot with dancing catkins. Here and there lurked a crimson bud, ready to catch the floating pollen. On the sloping banks below were splotches of violet and primrose, and, over all, hung the green shimmer of spring.

To the dormouse’s eyes the glare was, for the first few moments, as painful as before, but this time it was tempered with moisture. Great rain-drops swung on the swaying grass-stems and twinkled with a thousand prismatic colours. The slow drip of the woods resounded in his ears.

As his hearing sharpened, the old familiar sounds returned, the chirping of the titmice, the starling’s discord, the sniggering of the robin, the squirrel’s bullying cough. How he had hated the squirrel—a midget incarnation of mischief, whose whole life was spent in practical joking. How often had he heard that hateful cough shot into his ear, as My Lady Shadowtail whisked past him, a sinuous brown flash curling round the tree trunk! How often had he promptly dropped his hard-earned nut in consequence, only to see it seized by a field-mouse! How often had he swung at the end of a tapering twig, while the squirrel feinted at him with all four paws!

He looked up, and caught the squirrel’s eye.

“What, awake?” she shouted. “It’s not quite time for good little dormice. You wait till it’s dark, and see how cool it is. Why, even with my tail (and she bent it into a figure of eight to show its amplitude) it is hard enough to keep warm.”

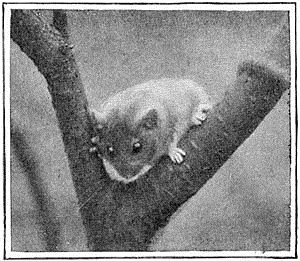

(L) MY LADY SHADOWTAIL. (R) MOTHER!

“Chuc!”

The dormouse had felt it coming, and had discreetly retired. As it was, the better part of the roof caved in, the result of slight mistiming on the part of the squirrel.

“I wish you wouldn’t do that,” said the dormouse.

He was addressing vacancy, for the squirrel had in the mean time completed the circuit of three tree-tops. She was back again, however, in time to catch the next remark.

“Have you any nuts?” said the dormouse. “I feel most horribly hungry, and this light is very trying to my eyes. It will have to be darker before I can hunt for any myself.”

“You’ll be asleep two hours before it’s dark,” said the squirrel, “and I haven’t any nuts, or rather, I haven’t the least idea where I put them. Didn’t you make a store?”

“Only a small one—seeds, I think,” said the dormouse. “I was very drowsy when I made it, and I daren’t hope that it is in good order.”

“Where is it?” said the squirrel.

“The second hazel on the left,” said the dormouse; “the third hollow from the top.”

The second hazel on the left was twenty yards away. Before the dormouse had finished speaking the squirrel had started, and the boughs by which she reached it were still quivering as she returned.

“There’s your store.”

The dormouse looked up, and gave a dolorous squeal of disappointment. A straggling nosegay was being thrust through the roof, and he realized at once that the seeds had sprouted.

“Why didn’t you nibble the ends off?” said the squirrel. “You can’t expect seeds to be seeds for ever. Oh, it’s your first hibernation, is it? Well, you’ll know better next time. Here’s a nut for you.” She had held it concealed in her palm, and produced it like a conjuror.

“She’s not such a bad sort, after all,” thought the dormouse, as he proceeded to examine the nut.

It was a hard nut, and would take some getting through. He sat back on his haunches, grasped it in his eight little fingers, gave it a twirl or two, and commenced gnawing three strokes a second. He gnawed for two minutes without a break.

It was harder than any other nut he remembered. He had never been more than a minute getting through one; sometimes they had obligingly split in half before he had fairly started. He tried another part, and worked even more vigorously than before.

Assuredly it was the very hardest nut in all the world. Twenty minutes’ hard work produced a small round hole, ten minutes more enlarged it so that he could thrust his lips inside. Then he sucked vigorously to secure the kernel, and secured instead a mouthful of black dust.

Of course the squirrel had known it all along. It did not need the guffaw he heard above to tell him that. This time he did not even protest. His spirit was broken. He was cold and tired and hungry. He merely huddled in a corner, still grasping the nut, and breathing in queer short gasps.

“Never mind, dormouse,” shouted the squirrel, “you will know a bad egg next time. Try this.”

For five seconds there was a faint rasping sound, then a sharp crack, and the rustle of two half-nutshells through the leaves. One of them struck the side of the hazel-stump and bounded off like an elastic ball. Before the dormouse had collected his wits, a fine kernel was thrust through the nest and the squirrel had once more regained her bough.

“Eat it,” she shrieked; “eat it before the sun goes down. It’s going now.”

And it was. Before a quarter of the kernel was accounted for, the western sky had turned to lurid orange; before the half was gone, the chill struck him. The nut dropped from his nerveless hands, his limbs tightened, his ears sank into his skin, his eyelids drooped, and he was asleep once more.

The primroses had long yielded pride of place to the daffodils; these in turn had paled before the marsh marigolds, but the most glorious yellow in the picture was the Sulphur Butterfly. He zigzagged lightly down the hedgerow, catching the sunshine at every turn, and the marigolds drooped their heads at the sight of him. Close to the nest he dropped on a briar-leaf, like a floating petal. He was more than colour now—he was form. For a full minute he poised there motionless, the most exquisitely graceful, the most exquisitely coloured of all our butterflies, and, for a full minute, the dormouse watched him.

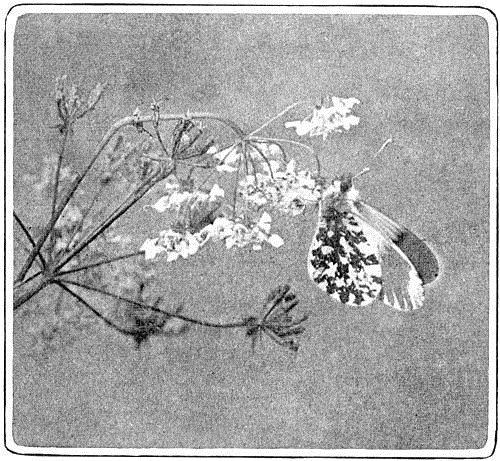

Next came a quivering, amber-tinted flight, resolved at rest into a delicate medley of green and white and saffron. It was the orange-tip, and the dormouse rejoiced, for the orange-tip meant spring. Such dainty frailty could never stand the winter.

To tell of all he heard and saw that day would fill a book. At first, as he peered through the crevices, he only grasped the more vivid tints—the azure of the hyacinth, the roseblush of the almond, the crimson glow of the clover, the purple of the foxglove. Then, as his senses quickened, the whole glorious colour-scale, from ashbud to whitethorn, stood revealed.

From heaven above came the skylark’s defiant challenge; from earth beneath the fussy scream of the blackbird; on all sides the tweetings, twitterings, chirrupings, chirrings and pipings of petulant finches, and, in tender modulation to the avian chorus, the deep-throated, innumerable, drowsy hum of insects. Colour and sound, love and war, it was spring indeed.

IT WAS THE ORANGE-TIP.

For the dormouse, one tiny penetrating note dominated all. He knew that the singer of that note was four-footed. Have you ever heard a cricket’s serenade? It was something like that. Have you ever heard a tree-creeper talking to itself? It was something like that also. He looked down and saw, as he expected, a round fur ball rolling in and out the grass-stems. At times the ball sat up and sniffed. He knew the puny fists and tapering snout at once. It was the shrewmouse. “Shrewmouse!” he cried, “is it time?” But the shrewmouse had crouched to dodge the shadow of a passing bird, and he saw him no more. However, he had seen enough. He stretched his hands and feet as though he would rack them from their sockets. Like Tennyson’s rabbit, he fondled his harmless face in the most elaborate of toilets, then he took one nibble at the remnant of the squirrel’s nut, and dropped off to sleep till the twilight.

BEFORE HIM LAY THE TWILIGHT WORLD HE LOVED.

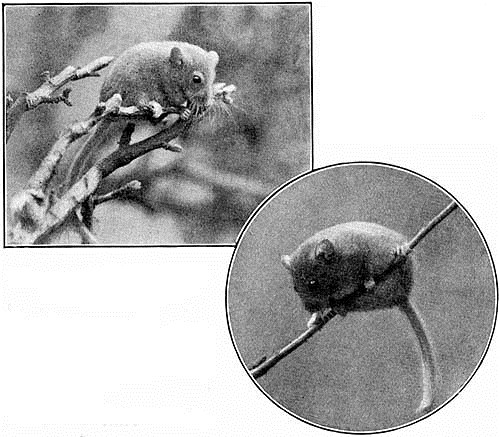

“FIGURE SOMEWHAT STOUT,” SAYS THE BOOK.

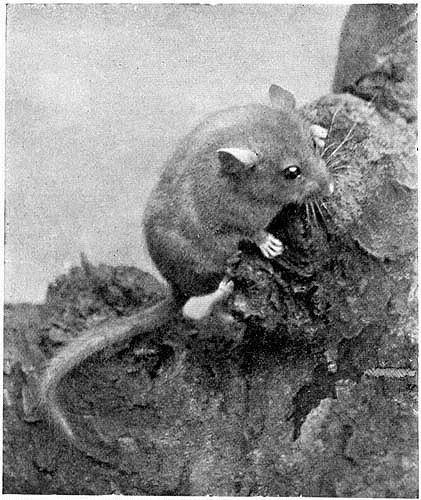

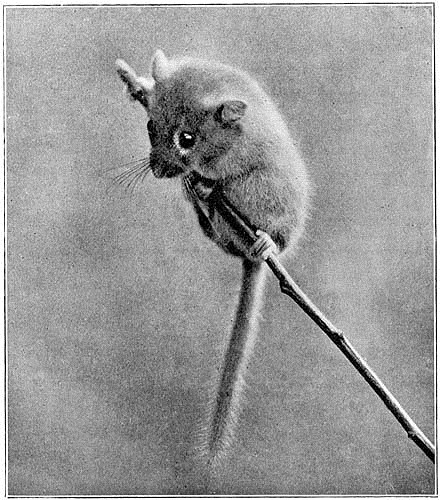

It is time to describe him.

“Figure somewhat stout,” says the book, “a single pair of pre-molars in each jaw, first toe of the fore-foot rudimentary, tail cylindrical,” etc. The dormouse was anything but stout—six months’ fasting, save for half a nut, had effectually restrained any tendency that way. No doubt in other respects he was in fair accordance with museum pattern, but he differed in one essential particular—he was alive.

HIS EYES? NOR PEN NOR CAMERA CAN PRESENT THEM.

His colour? When he had first retired to rest he had closely resembled a young red vole, buff grey all over save for his white waistcoat and the hair-parting along his back and down the ridges of his limbs. This was a delicate auburn. During his sleep the auburn had overspread his back, softened into cream colour on his sides, and thence into a pure white front. Ages ago his ancestors had been white all over; now, amid changed surroundings, the white only lingered where it was least conspicuous.

His eyes? Nor pen nor camera can present them. Imagine a black pearl imprisoning a diamond; imagine a dewdrop trembling on polished jet; add to these beauties life, and you will have the dormouse eye.

His tail? Distichous, say the books. Feathers are mostly distichous, hair-partings are distichous, the moustache is distichous. So is the dormouse tail; but the hairs along it do more than merely part. They curl, upwards from the root, downwards to the point, and form a plume.

The plume is a natural parachute, not so obvious, perhaps, as in the squirrel’s case, but, weight for weight, of equal service.

His feet? Ten toes behind and eight before, sharp-pointed toes that grip the slenderest twig, and catch the slightest foothold in the bark.

His ears? Small, say the books. Not small, but rather hidden in the deep surrounding fur.

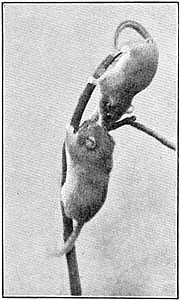

Had you seen the dormouse at the moment of his final awakening, you might have recognized him from this description. A few minutes later and the grey, flitting shadow might easily have baffled you. For, as he reached the surface of his nest, the sun went down.

SHARP-POINTED TOES THAT CATCH THE SLIGHTEST FOOTHOLD IN THE BARK.

Before him, at last, lay the twilight world he loved. Nature had ceased her noise and commenced her melody. From the brook below came the dull plash of the rising trout; now and then one could catch a stealthy rustle in the herbage—the beetles were abroad, ay and the mice and the beasts of prey; a hare paced by with easy lilting stride; his gentle footfall hardly stirred the dust. In the distance sounded the cry of a lost soul. It was the barn owl starting on her rounds. The dormouse cowered back until she passed—white—gleaming, swift and silent as a moth.

IT WAS THE SAME SOFT FUR THAT HE HAD NESTLED IN LAST YEAR.

ONCE MORE HE FELT THE MAGIC PULSE OF LIFE WITHIN HIM.

There was no discordant note. Wood, meadow, and hedgerow were bathed in liquid blue. The very tree trunks stood out as indigo against the sky. Daisy and marigold, hyacinth and clover were attuned to the same soothing minor chord. The work-a-day world was at rest, but the sleep-a-day world was holding high revel.

Before he was halfway down the stump he had caught the glint of twenty pairs of eyes. The voles and wood-mice had waited, like himself, until the owl had passed. Before each tuft of grass now stood its latest tenant. From beneath the root of a neighbouring hazel came a stealthy procession of five bank voles. Each, as it gained the entrance, performed its normal round. First it sniffed for weasel, then it sat up and washed its face, then it sniffed again, finally it stole off, foraging among the grass-stems. He saw his friend the shrewmouse scuffling with its mate; he saw the wood-mice nut-grubbing; he saw the night reunion of the stump-tailed voles; but the first of his own kind that he saw was mother.

He had swung himself to the top of a broken twig, and, as he looked down, perceived her climbing stiffly up towards him. Mother had aged since the autumn, but, when she drew closer, he knew her well enough; it was the same soft fur that he had nestled in last year.

Together they went out into the night. Once more he felt the magic pulse of life within him, and ran to the top of the hedge and down again twenty times for the mere joy of running. Head upwards he flew, head downwards, backwards, forwards, sideways. Sometimes he paused for a moment, lightly balanced on a branch end, then swung himself to the next friendly projection. Sometimes there was no pause. In one easy unbroken course he travelled to the end, cleared the intervening gap, and landed on the neighbouring branch below. He never missed, he never stumbled; for he was tumbler and wire-walker and saltimbanque in one.

HE WAITED FOR HER AS LONG AS HE DARED.