полная версия

полная версия"Wee Tim'rous Beasties": Studies of Animal life and Character

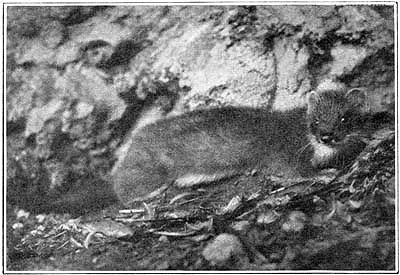

Next spoke the stoat, the swash-buckler. He cleared his throat with a short, rasping bark, glared round him, and began—

“I am the only flesh-eater among you all,” said he. The hedgehog’s smile broadened, but he said nothing. “Therefore I have bigger game to tackle than any of you. Therefore I am better armed. Scores of bats I have eaten in my time. I could climb your chestnut if I cared to, noctule, and eat the colony. I would, if you were not so evil-smelling.” (This from the stoat!) “Scores of water-rats have I eaten, too. Look at my long, lithe body. What burrow is too small for it? Look at my teeth. What rodent has a chance against them? I fear nothing, not even man himself. I can swim, I can run, I can climb, I can hunt by scent, and I am cunning as a fox. From my fur, when I am dead, comes the imperial ermine. Would you pit yourself against me, hedgehog?”

NEXT SPOKE THE STOAT, THE SWASH-BUCKLER.

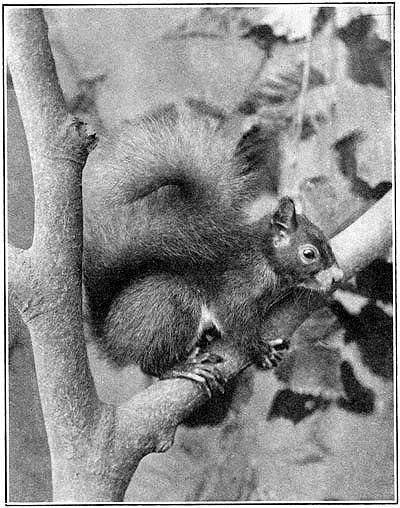

“I WOULD,” SAID THE SQUIRREL.

“I would,” said the squirrel. Like the bats, he was some way off the ground; also he had mapped up a clear course of forty yards among the tree-tops, so he spoke recklessly. “The stoat is an amateur climber.” (“Wait till I get to your nursery!” snarled the stoat.) “He has no idea of taking cover. A treed stoat against a human is doomed. Look at his black-smudged tail—only a trifle better than a weasel’s. It reminds me of my summer moult—but it’s worse; and, in the summer, even I must trust more to my hands and feet. I, the most skilful gymnast in the country, save only the marten, and there are too few of them to count. Give me my winter parachute, and see me then. Who can thread the woods like me? From end to end I fly, skimming the tree-tops and never touching ground. Yet, if the fancy takes me, I can cover land or water faster than any stoat. From my fur, when I am dead, comes the camel-hair brush.”

Next came the dormouse. “Sleep is the best defence of all,” he said. “Sleep and being very small indeed, and never coming out except after sundown, and having great big eyes, so that you can see things like stoats long before they see you. Offence I know nothing of, unless it’s eating beetles.”

After him the wood-mouse. “Give me a good burrow underground,” said he. “Make it among branching roots, with half a dozen entrances and exits, and I defy the weasel, let alone the stoat. But in the winter, when cover is scanty, sleep and a store of nuts is best of all. Beans are no good—they rot away. Earth-stored nuts, tight packed, are the sweetest things I know.”

“What of summer?” said the hedgehog.

“Weight for weight,” said the mouse, “I can tackle anything that moves. As for voles and house-mice, I can fight two at once. When I am giving much away, I like my burrow handy.”

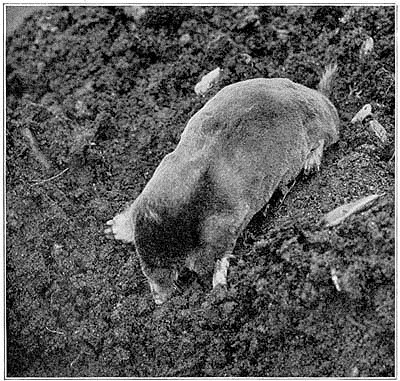

TWO FIELDS AWAY YOU CAN SEE MY FORTRESSES.

“WHO TALKS OF BURROWS,” SAID THE MOLE.

“Who talks of burrows?” said the mole. “Where is there tunnel-builder like myself? Two fields away you can see my fortresses. You can see them plainly, tunnelled maze and rounded nest and all. Some prying human has turned his vacant mind to nature-study, and made a clumsy section of a pair. Look at each in turn. Mark the one tunnel that leads upward to the nest, mark the two galleries that surround it, mark that they wind in a spiral, and are not joined by shafts at intervals. That would so weaken the surroundings as to leave the nest an easy prey to scratching weasel. Why is the spiral made? To cheat inquiry; a dozen tunnels join it from the run; from it are a dozen exits to the surrounding field. One tunnel only leads into the nest. Only the moles know that one. Alone I did it, save for my wife, who hindered me. Alone I moved two hundredweight of earth. Nor do my qualities end here. Were I fifty times as big, I would be lord of creation. Where can you find fiercer courage than mine; where, bulk for bulk, more mighty strength? What monster, think you, would an elephant, built for burrowing, be? For my weight, I am the strongest thing that lives. One creature, and one only, approaches me; that is the mole-cricket. Let him speak for himself.”

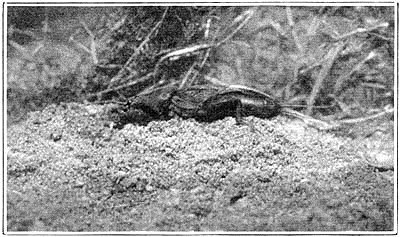

THE MOLE-CRICKET TURNED UP FROM NOWHERE IN PARTICULAR.

The mole-cricket turned up from nowhere in particular, and his voice was the tinkling of a silver bell. It would have taken a score of him to make a mole.

“I am older than the mole,” he said, “yet from him I take my name. In dry ground I make poor progress; where it is muddy and swampy, I can run through it, like a fish through water. When the mole came into being, he borrowed the pattern of my fore feet—shovel and pick and spade in one. Like me, he learnt to run backwards or forwards, and that is why his hair has no set in it. Whichever way he goes, the clinging dust is swept from off its surface. He comes from grubby depths as polished as a pin. And so do I; but from a different cause. I am so highly polished that the damp soil cannot cleave to me.”

“Burrowing,” said the hedgehog, “is a low form of defence. What says the water-rat?”

“I burrow, too,” said the water-rat. “If I have time, I burrow in the water. I part the surface with the tiniest ripple, keeping my fore feet close packed to my sides, and swim with hind legs only, below the surface, neatly as a natterjack. If I were better treated, I should never burrow in the banks at all. But I must have somewhere to go to when my breath fails me. I eat the mare’s tail and the pith of reed-stems. That does no one any harm, not even a trout-preserver. But of all good viands, commend me to a parsnip.”

“This is neither defence nor offence,” said the hedgehog.

“The only offensive thing I have is a pair of incisors,” said the water-rat. “They are orange-yellow and very strong. As regards defence, I can do more in the water than most.”

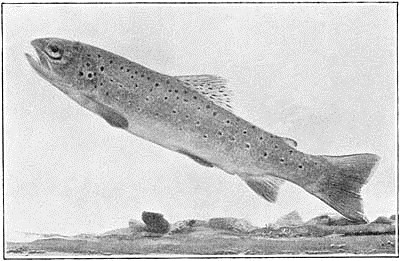

“NOT MORE THAN ME,” THE YOUNG TROUT BROKE IN.

“Not more than me,” the young trout broke in. He flung his nose jauntily against the surface, and the surface swung from it in widening eddies, circle after circle. “I can be up to the weir and down again before you are halfway across the stream. When humans build their destroyers, they model them on me. I know that, because I have seen their clumsy models, trout-shaped, save the mark!”

“That is enough from any one of your years,” said the hedgehog. “Little river-fishes run away from big river-fishes, and big river-fishes run away from bigger river-fishes, and they all run away from the otter.”

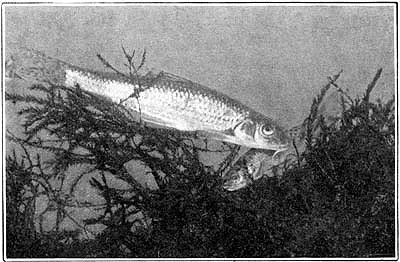

The jack that lived in the deep below the pollard grinned, but said nothing. The jack knew better, but he never says anything. But the gudgeon and the troutling were terrified at the notion of bigger fishes, and made straight for the weeds.

BUT THE GUDGEON AND TROUTLING MADE STRAIGHT FOR THE WEEDS.

“What think the caterpillars?” said the hedgehog.

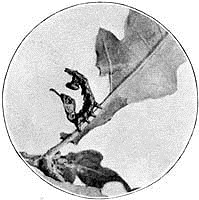

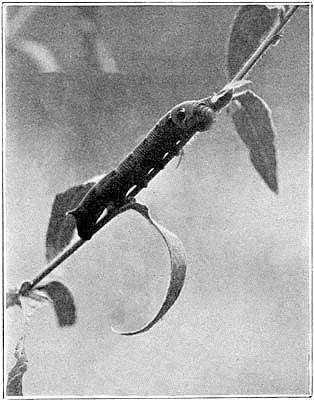

IT WAS THE LOBSTER-MOTH-TO-BE THAT SPOKE FIRST.

MOST OF THEM FLING THEIR HEADS BACK, ARCH THEIR NECKS, AND PLAY AT BEING SNAKES.

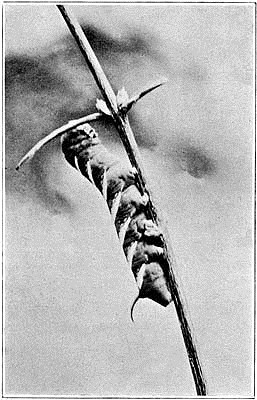

The caterpillars were studying moral invisibility in a hundred different ways, for insect life is the most highly specialized of all. It was the lobster-moth-to-be that spoke first. He bent his head backwards until it touched his tail, folded the knee-joints of his skinny legs, and began—

“It is all bluff,” said he, “caterpillars are past-masters of bluff. Look at the hawkmoths, fat, flabby, bloated things, with curly tails. Most of them fling their heads back, arch their necks, and play at being snakes. Some grow eyes upon them, not real eyes, but markings which serve as such, enough to scare the average chuckle-headed bird. Sometimes they trust to vein-markings on their bodies, which turn them into casual misshapen leaves. Sometimes they liken themselves to twigs—”

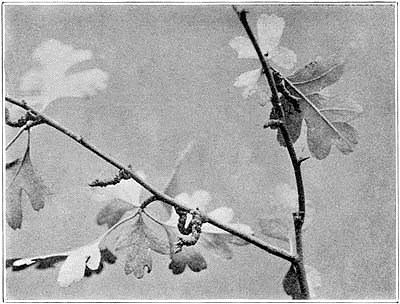

“That is what we do,” cried the loopers. Each branch of the oak had its loopers, feeding cheerfully, transforming themselves to twigs, and shamming death in quick succession.

NOT REAL EYES BUT MARKINGS WHICH SERVE AS SUCH.

“Sometimes,” continued the lobster-moth-to-be, “they are, like myself, really worth eating. Then, mere vulgar imitation bluff is of little avail. To be a withered leaf is my first line of defence; if the ichneumon buzzes nearer, I shift my ground and become a spider. I am the only caterpillar in the country with spider-legs; when they are stretched to their full length and quivering, they are worse to look at than the real thing. Should even this fail me, I show the imitation scar on my fourth body-ring. That usually clinches the matter. The ichneumon fondly imagines that I am already occupied. So, if I am lucky, I turn at length to dingy pupa, and thus preserve my race.”

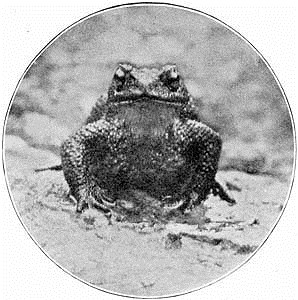

“Will you hear an amphibian?” said the toad. He came from the centre of a grass-tuft, and spoke with solemn deliberation. “Not one of you is more persecuted than I. From time immemorial I have been the loadstone of credulity, and—I am altogether defenceless. I am never worth eating, for the shock of capture opens every pore on my skin, drenching me with what the poets class as venom. So I am usually thrown aside with a broken back. For centuries I was thought to have a jewel in my head. How many of my hapless ancestors were tortured for that jewel! With the toad’s death, the jewel was believed to vanish. How many have been ‘larned to be a toad’ by baffled, disappointed rustics! That is what puts the sad expression in my eye. How have I survived it all? By dogged perseverance. I lay so many eggs that one at least must survive. Thus is the balance of the race preserved. I myself was one of five hundred, the only one that reached maturity. Yet all were in the same long ribbon coil. The swan that gulped the coil, gulped all but me. I dropped into the brook alone, and there I quietly passed through my novitiate, egg to tadpole, tadpole to toadling, toadling to toad. When my tail was absorbed into my body, I sought a land-retreat. There I have spent my time for twenty years. None of you know it, and none ever will. I leave it only at twilight, and, as you pass, I shield my face with my fore feet. Froggin is much the same; nothing but his prolific quality saves him.”

EACH BRANCH OF THE OAK HAD ITS LOOPERS.

“WILL YOU HEAR AN AMPHIBIAN?” SAID THE TOAD.

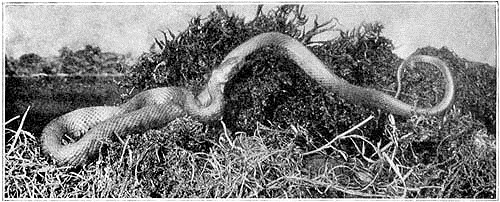

“Froggin is at least worth eating,” said the grass-snake. He lay with all his four-foot length displayed in graceful sinuous curves, and was listened to in silence. Nothing loves a snake, however harmless. “With me, as with the caterpillars, it is mostly bluff. I can swing back my head, and flatten the nape of my neck, as well as any deadly adder. I can also strike, but there is no poison behind the blow. My only weapon of offence is smell, a sickening musty smell, that makes the enemy loose his hold. Once I am halfway down a hole, I’m safe. I set my ratchet scales against the sides, and nothing can dislodge me. Only a jerk is dangerous, and that must be accomplished before I am fairly fixed.”

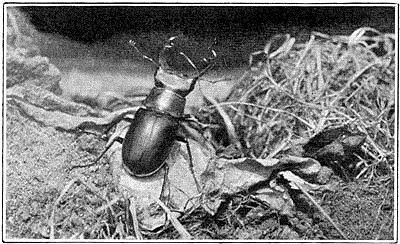

“I am armour-clad,” said the stag-beetle. “Could there be better method of defence? Look at the sliding joints of my breastplate. Human skill has copied it, but never has surpassed it. My horns look formidable, but for offence are useless. They are far from my eyes, and move but slowly. Give me time, and I can crush a tender twig between them, and suck its juices. That is all the purpose they serve me, yet they look like branching antlers, and that also is something.”

“FROGGIN IS AT LEAST WORTH EATING,” SAID THE GRASS-SNAKE.

“I AM ARMOUR-CLAD,” SAID THE STAG-BEETLE.

“I have heard you all,” said the hedgehog. “I have heard the flier’s point of view from the bat, the gymnast’s point of view from the squirrel, the swimmer’s point of view from the water-rat, and the assassin’s point of view from the stoat.” For a moment he coiled himself up with a snap, but the stoat made no remark, so he slowly uncoiled himself, and resumed. “Yet I maintain my original contention, there is nothing like spines. ‘The fox’s tricks are many; one is enough for the urchin.’ What is the one unfailing, all-sufficing trick? The proper and judicious use of spines. All of you would use spines if you could. Most of you do. Think of the bramble-thickets, think of the furze, the last resort of valiant stoat and viper, think of the holly, where the sparrows roost.

“Spines are the proved asylum of the spineless. Nature has flung them broadcast. She starts low down among the plants, thorn and thistle, gorse and cactus. Then she turns to the sea-urchins and caterpillars and beetles, then she fashions the globe-fish and thorny devil-lizard, then she comes to the birds—spikes are their only weapons—lastly, in me and mine, she reaches the fulness of perfection.

“Think of the purposes spines serve me. Which of you defies the fox or terrier in the open? I leave the fliers out—running away is not defence. To me a fight is child’s play. The more inquisitive my foe, the tighter do I clinch myself together. They get more harm than I do.”

The last few words were spoken from within. The stoat approached gingerly, and turned the hedgehog over, seeking for a place to jump at. The bat wheeled across him, and swerved at the suspicion of those rigid spears. The caterpillars betook themselves once more to feeding. The water-rat slipped quietly down the stream,—she still feared the stoat. The squirrel ran openly down his tree-trunk, and secretly up the far side of it. The fear of the stoat was on him too. So the moon rose, and, for most, the chance of sport that night passed away.

The hedgehog remained coiled for an hour. Then he shambled away, well satisfied. First he eat two pheasant eggs, then a belated frog, and then a nestling blackbird. As the sun mounted the eastern sky he once more sought the pile of leaves that lay against the hen-house.

THE END