полная версия

полная версияThe Harbours of England

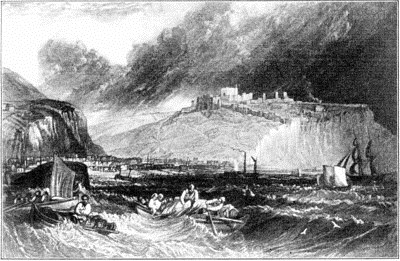

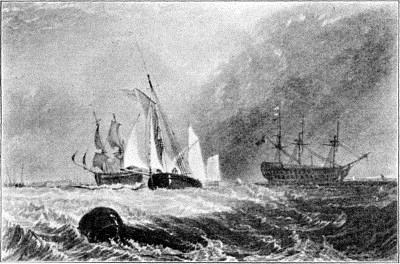

I.—DOVER

This port has some right to take precedence of others, as being that assuredly which first exercises the hospitality of England to the majority of strangers who set foot on her shores. I place it first therefore among our present subjects; though the drawing itself, and chiefly on account of its manifestation of Turner's faulty habit of local exaggeration, deserves no such pre-eminence. He always painted, not the place itself, but his impression of it, and this on steady principle; leaving to inferior artists the task of topographical detail; and he was right in this principle, as I have shown elsewhere, when the impression was a genuine one; but in the present case it is not so. He has lost the real character of Dover Cliffs by making the town at their feet three times lower in proportionate height than it really is; nor is he to be justified in giving the barracks, which appear on the left hand, more the air of a hospice on the top of an Alpine precipice, than of an establishment which, out of Snargate street, can be reached, without drawing breath, by a winding stair of some 170 steps; making the slope beside them more like the side of Skiddaw than what it really is, the earthwork of an unimportant battery.

This design is also remarkable as an instance of that restlessness which was above noticed even in Turner's least stormy seas. There is nothing tremendous here in scale of wave, but the whole surface is fretted and disquieted by torturing wind; an effect which was always increased during the progress of the subjects, by Turner's habit of scratching out small sparkling lights, in order to make the plate "bright," or "lively."17 In a general way the engravers used to like this, and, as far as they were able, would tempt Turner farther into the practice, which was precisely equivalent to that of supplying the place of healthy and heart-whole cheerfulness by dram-drinking.

The two sea-gulls in the front of the picture were additions of this kind, and are very injurious, confusing the organization and concealing the power of the sea. The merits of the drawing are, however, still great as a piece of composition. The left-hand side is most interesting, and characteristic of Turner: no other artist would have put the round pier so exactly under the round cliff. It is under it so accurately, that if the nearly vertical falling line of that cliff be continued, it strikes the sea-base of the pier to a hair's breadth. But Turner knew better than any man the value of echo, as well as of contrast,—of repetition, as well as of opposition. The round pier repeats the line of the main cliff, and then the sail repeats the diagonal shadow which crosses it, and emerges above it just as the embankment does above the cliff brow. Lower, come the opposing curves in the two boats, the whole forming one group of sequent lines up the whole side of the picture. The rest of the composition is more commonplace than is usual with the great master; but there are beautiful transitions of light and shade between the sails of the little fishing-boat, the brig behind her, and the cliffs. Note how dexterously the two front sails18 of the brig are brought on the top of the white sail of the fishing-boat to help to detach it from the white cliffs.

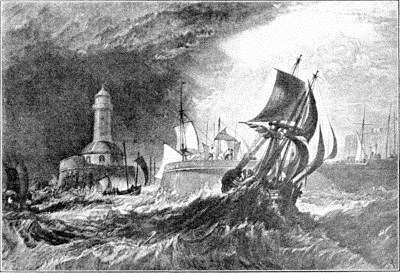

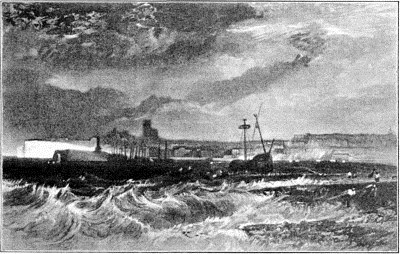

II.—RAMSGATE

This, though less attractive, at first sight, than the former plate, is a better example of the master, and far truer and nobler as a piece of thought. The lifting of the brig on the wave is very daring; just one of the things which is seen in every gale, but which no other painter than Turner ever represented; and the lurid transparency of the dark sky, and wild expression of wind in the fluttering of the falling sails of the vessel running into the harbor, are as fine as anything of the kind he has done. There is great grace in the drawing of this latter vessel: note the delicate switch forward of her upper mast.

There is a very singular point connected with the composition of this drawing, proving it (as from internal evidence was most likely) to be a record of a thing actually seen. Three years before the date of this engraving Turner had made a drawing of Ramsgate for the Southern Coast series. That drawing represents the same day, the same moment, and the same ships, from a different point of view. It supposes the spectator placed in a boat some distance out at sea, beyond the fishing-boats on the left in the present plate, and looking towards the town, or into the harbor. The brig, which is near us here, is then, of course, in the distance on the right; the schooner entering the harbor, and, in both plates, lowering her fore-topsail, is, of course, seen foreshortened; the fishing-boats only are a little different in position and set of sail. The sky is precisely the same, only a dark piece of it, which is too far to the right to be included in this view, enters into the wider distance of the other, and the town, of course, becomes a more important object.

The persistence in one conception furnishes evidence of the very highest imaginative power. On a common mind, what it has seen is so feebly impressed, that it mixes other ideas with it immediately; forgets it—modifies it—adorns it,—does anything but keep hold of it. But when Turner had once seen that stormy hour at Ramsgate harbor-mouth, he never quitted his grasp of it. He had seen the two vessels; one go in, the other out. He could have only seen them at that one moment—from one point; but the impression on his imagination is so strong, that he is able to handle it three years afterwards, as if it were a real thing, and turn it round on the table of his brain, and look at it from the other corner. He will see the brig near, instead of far off: set the whole sea and sky so many points round to the south, and see how they look, so. I never traced power of this kind in any other man.

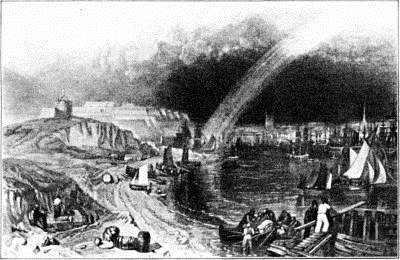

III.—PLYMOUTH

The drawing for this plate is one of Turner's most remarkable, though not most meritorious, works: it contains the brightest rainbow he ever painted, to my knowledge; not the best, but the most dazzling. It has been much modified in the plate. It is very like one of Turner's pieces of caprice to introduce a rainbow at all as a principal feature in such a scene; for it is not through the colors of the iris that we generally expect to be shown eighteen-pounder batteries and ninety-gun ships.

Whether he meant the dark cloud (intensely dark blue in the original drawing), with the sunshine pursuing it back into distance; and the rainbow, with its base set on a ship of battle, to be together types of war and peace, and of the one as the foundation of the other, I leave it to the reader to decide. My own impression is, that although Turner might have some askance symbolism in his mind, the present design is, like the former one, in many points a simple reminiscence of a seen fact.19

However, whether reminiscent or symbolic, the design is, to my mind, an exceedingly unsatisfactory one, owing to its total want of principal subject. The fort ceases to be of importance because of the bank and tower in front of it; the ships, necessarily for the effect, but fatally for themselves, are confused, and incompletely drawn, except the little sloop, which looks paltry and like a toy; and the foreground objects are, for work of Turner, curiously ungraceful and uninteresting.

It is possible, however, that to some minds the fresh and dewy space of darkness, so animated with latent human power, may give a sensation of great pleasure, and at all events the design is worth study on account of its very strangeness.

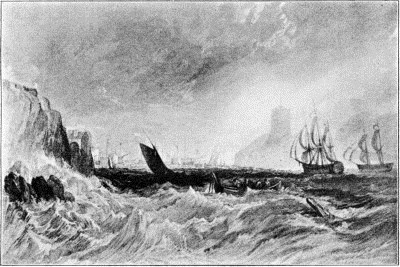

IV.—CATWATER

I have placed in the middle of the series those pictures which I think least interesting, though the want of interest is owing more to the monotony of their character than to any real deficiency in their subjects. If, after contemplating paintings of arid deserts or glowing sunsets, we had come suddenly upon this breezy entrance to the crowded cove of Plymouth, it would have gladdened our hearts to purpose; but having already been at sea for some time, there is little in this drawing to produce renewal of pleasurable impression: only one useful thought may be gathered from the very feeling of monotony. At the time when Turner executed these drawings, his portfolios were full of the most magnificent subjects—coast and inland,—gathered from all the noblest scenery of France and Italy. He was ready to realize these sketches for any one who would have asked it of him, but no consistent effort was ever made to call forth his powers; and the only means by which it was thought that the public patronage could be secured for a work of this kind, was by keeping familiar names before the eye, and awakening the so-called "patriotic," but in reality narrow and selfish, associations belonging to well-known towns or watering-places. It is to be hoped, that when a great landscape painter appears among us again, we may know better how to employ him, and set him to paint for us things which are less easily seen, and which are somewhat better worth seeing, than the mists of the Catwater, or terraces of Margate.

V.—SHEERNESS

I look upon this as one of the noblest sea-pieces which Turner ever produced. It has not his usual fault of over-crowding or over-glitter; the objects in it are few and noble, and the space infinite. The sky is quite one of his best: not violently black, but full of gloom and power; the complicated roundings of its volumes behind the sloop's mast, and downwards to the left, have been rendered by the engraver with notable success; and the dim light entering along the horizon, full of rain, behind the ship of war, is true and grand in the highest degree. By comparing it with the extreme darkness of the skies in the Plymouth, Dover, and Ramsgate, the reader will see how much more majesty there is in moderation than in extravagance, and how much more darkness, as far as sky is concerned, there is in gray than in black. It is not that the Plymouth and Dover skies are false,—such impenetrable forms of thunder-cloud are amongst the commonest phenomena of storm; but they have more of spent flash and past shower in them than the less passionate, but more truly stormy and threatening, volumes of the sky here. The Plymouth storm will very thoroughly wet the sails, and wash the decks, of the ships at anchor, but will send nothing to the bottom. For these pale and lurid masses, there is no saying what evil they may have in their thoughts, or what they may have to answer for before night. The ship of war in the distance is one of many instances of Turner's dislike to draw complete rigging; and this not only because he chose to give an idea of his ships having seen rough service, and being crippled; but also because in men-of-war he liked the mass of the hull to be increased in apparent weight and size by want of upper spars. All artists of any rank share this last feeling. Stanfield never makes a careful study of a hull without shaking some or all of its masts out of it first, if possible. See, in the Coast Scenery, Portsmouth harbor, Falmouth, Hamoaze, and Rye old harbors; and compare, among Turner's works, the near hulls in the Devonport, Saltash, and Castle Upnor, and distance of Gosport. The fact is, partly that the precision of line in the complete spars of a man-of-war is too formal to come well into pictorial arrangements, and partly that the chief glory of a ship of the line is in its aspect of being "one that hath had losses."

The subtle varieties of curve in the drawing of the sails of the near sloop are altogether exquisite; as well as the contrast of her black and glistering side with those sails, and with the sea. Examine the wayward and delicate play of the dancing waves along her flank, and between her and the brig in ballast, plunging slowly before the wind; I have not often seen anything so perfect in fancy, or in execution of engraving.

The heaving and black buoy in the near sea is one of Turner's "echoes," repeating, with slight change, the head of the sloop with its flash of luster. The chief aim of this buoy is, however, to give comparative lightness to the shadowed part of the sea, which is, indeed, somewhat overcharged in darkness, and would have been felt to be so, but for this contrasting mass. Hide it with the hand, and this will be immediately felt. There is only one other of Turner's works which, in its way, can be matched with this drawing, namely, the Mouth of the Humber in the River Scenery. The latter is, on the whole, the finer picture; but this by much the more interesting in the shipping.

VI.—MARGATE

This plate is not, at first sight, one of the most striking of the series; but it is very beautiful, and highly characteristic of Turner.20 First, in its choice of subjects: for it seems very notably capricious in a painter eminently capable of rendering scenes of sublimity and mystery, to devote himself to the delineation of one of the most prosaic of English watering-places—not once or twice, but in a series of elaborate drawings, of which this is the fourth. The first appeared in the Southern Coast series, and was followed by an elaborate drawing on a large scale, with a beautiful sunrise; then came another careful and very beautiful drawing in the England and Wales series; and finally this, which is a sort of poetical abstract of the first. Now, if we enumerate the English ports one by one, from Berwick to Whitehaven, round the island, there will hardly be found another so utterly devoid of all picturesque or romantic interest as Margate. Nearly all have some steep eminence of down or cliff, some pretty retiring dingle, some roughness of old harbor or straggling fisher-hamlet, some fragment of castle or abbey on the heights above, capable of becoming a leading point in a picture; but Margate is simply a mass of modern parades and streets, with a little bit of chalk cliff, an orderly pier, and some bathing-machines. Turner never conceives it as anything else; and yet for the sake of this simple vision, again and again he quits all higher thoughts. The beautiful bays of Northern Devon and Cornwall he never painted but once, and that very imperfectly. The finest subjects of the Southern Coast series—the Minehead, Clovelly, Ilfracombe, Watchet, East and West Looe, Tintagel, Boscastle—he never touched again; but he repeated Ramsgate, Deal, Dover, and Margate, I know not how often.

Whether his desire for popularity, which, in spite of his occasional rough defiances of public opinion, was always great, led him to the selection of those subjects which he thought might meet with most acceptance from a large class of the London public, or whether he had himself more pleasurable associations connected with these places than with others, I know not; but the fact of the choice itself is a very mournful one, considered with respect to the future interests of art. There is only this one point to be remembered, as tending to lessen our regret, that it is possible Turner might have felt the necessity of compelling himself sometimes to dwell on the most familiar and prosaic scenery, in order to prevent his becoming so much accustomed to that of a higher class as to diminish his enthusiasm in its presence. Into this probability I shall have occasion to examine at greater length hereafter.

The plate of Margate now before us is nearly as complete a duplicate of the Southern Coast view as the previous plate is of that of Ramsgate; with this difference, that the position of the spectator is here the same, but the class of ship is altered, though the ship remains precisely in the same spot. A piece of old wreck, which was rather an important object to the left of the other drawing, is here removed. The figures are employed in the same manner in both designs.

The details of the houses of the town are executed in the original drawing with a precision which adds almost painfully to their natural formality. It is certainly provoking to find the great painter, who often only deigns to bestow on some Rhenish fortress or French city, crested with Gothic towers, a few misty and indistinguishable touches of his brush, setting himself to indicate, with unerring toil, every separate square window in the parades, hotels, and circulating libraries of an English bathing-place.

The whole of the drawing is well executed, and free from fault or affectation, except perhaps in the somewhat confused curlings of the near sea. I had much rather have seen it breaking in the usual straightforward way. The brilliant white of the piece of chalk cliff is evidently one of the principal aims of the composition. In the drawing the sea is throughout of a dark fresh blue, the sky grayish blue, and the grass on the top of the cliffs a little sunburnt, the cliffs themselves being left in the almost untouched white of the paper.

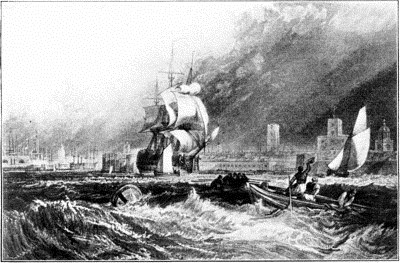

VII.—PORTSMOUTH

This beautiful drawing is a third recurrence by Turner to his earliest impression of Portsmouth, given in the Southern Coast series. The buildings introduced differ only by a slight turn of the spectator towards the right; the buoy is in the same spot; the man-of-war's boat nearly so; the sloop exactly so, but on a different tack; and the man-of-war, which is far off to the left at anchor in the Southern Coast view, is here nearer, and getting up her anchor.

The idea had previously passed through one phase of greater change, in his drawing of "Gosport" for the England, in which, while the sky of the Southern Coast view was almost cloud for cloud retained, the interest of the distant ships of the line had been divided with a collier brig and a fast-sailing boat. In the present view he returns to his early thought, dwelling, however, now with chief insistence on the ship of the line, which is certainly the most majestic of all that he has introduced in his drawings.

It is also a very curious instance of that habit of Turner's before referred to (p. {ref}27), of never painting a ship quite in good order. On showing this plate the other day to a naval officer, he complained of it, first that "the jib21 would not be wanted with the wind blowing out of harbor," and, secondly, that "a man-of-war would never have her foretop-gallant sail set, and her main and mizzen top-gallants furled:—all the men would be on the yards at once."

I believe this criticism to be perfectly just, though it has happened to me, very singularly, whenever I have had the opportunity of making complete inquiry into any technical matter of this kind, respecting which some professional person had blamed Turner, that I have always found, in the end, Turner was right, and the professional critic wrong, owing to some want of allowance for possible accidents, and for necessary modes of pictorial representation. Still, this cannot be the case in every instance; and supposing my sailor informant to be perfectly right in the present one, the disorderliness of the way in which this ship is represented as setting her sails, gives us farther proof of the imperative instinct in the artist's mind, refusing to contemplate a ship, even in her proudest moments, but as in some way over-mastered by the strengths of chance and storm.

The wave on the left hand beneath the buoy, presents a most interesting example of the way in which Turner used to spoil his work by retouching. All his truly fine drawings are either done quickly, or at all events straight forward, without alteration: he never, as far as I have examined his works hitherto, altered but to destroy. When he saw a plate look somewhat dead or heavy, as, compared with the drawing, it was almost sure at first to do, he used to scratch out little lights all over it, and make it "sparkling"; a process in which the engravers almost unanimously delighted,22 and over the impossibility of which they now mourn, declaring it to be hopeless to engrave after Turner, since he cannot now scratch their plates for them. It is quite true that these small lights were always placed beautifully; and though the plate, after its "touching," generally looked as if ingeniously salted out of her dredging-box by an artistical cook, the salting was done with a spirit which no one else can now imitate. But the original power of the work was forever destroyed. If the reader will look carefully beneath the white touches on the left in this sea, he will discern dimly the form of a round nodding hollow breaker. This in the early state of the plate is a gaunt, dark, angry wave, rising at the shoal indicated by the buoy;—Mr. Lupton has fac-similed with so singular skill the scratches of the penknife by which Turner afterwards disguised this breaker, and spoiled his picture, that the plate in its present state is almost as interesting as the touched proof itself; interesting, however, only as a warning to all artists never to lose hold of their first conception. They may tire even of what is exquisitely right, as they work it out, and their only safety is in the self-denial of calm completion.

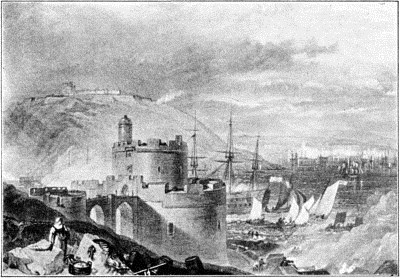

VIII.—FALMOUTH

This is one of the most beautiful and best-finished plates of the series, and Turner has taken great pains with the drawing; but it is sadly open to the same charges which were brought against the Dover, of an attempt to reach a false sublimity by magnifying things in themselves insignificant. The fact is that Turner, when he prepared these drawings, had been newly inspired by the scenery of the Continent; and with his mind entirely occupied by the ruined towers of the Rhine, he found himself called upon to return to the formal embrasures and unappalling elevations of English forts and hills. But it was impossible for him to recover the simplicity and narrowness of conception in which he had executed the drawing of the Southern Coast, or to regain the innocence of delight with which he had once assisted gravely at the drying of clothes over the limekiln at Comb Martin, or penciled the woodland outlines of the banks of Dartmouth Cove. In certain fits of prosaic humorism, he would, as we have seen, condemn himself to delineation of the parades of a watering-place; but the moment he permitted himself to be enthusiastic, vaster imaginations crowded in upon him: to modify his old conception in the least, was to exaggerate it; the mount of Pendennis is lifted into rivalship with Ehrenbreitstein, and hardworked Falmouth glitters along the distant bay, like the gay magnificence of Resina or Sorrento.

This effort at sublimity is all the more to be regretted, because it never succeeds completely. Shade, or magnify, or mystify as he may, even Turner cannot make the minute neatness of the English fort appeal to us as forcibly as the remnants of Gothic wall and tower that crown the Continental crags; and invest them as he may with smoke or sunbeam, the details of our little mounded hills will not take the rank of cliffs of Alp, or promontories of Apennine; and we lose the English simplicity, without gaining the Continental nobleness.

I have also a prejudice against this picture for being disagreeably noisy. Wherever there is something serious to be done, as in a battle piece, the noise becomes an element of the sublimity; but to have great guns going off in every direction beneath one's feet on the right, and all round the other side of the castle, and from the deck of the ship of the line, and from the battery far down the cove, and from the fort on the top of the hill, and all for nothing, is to my mind eminently troublesome.

The drawing of the different wreaths and depths of smoke, and the explosive look of the flash on the right, are, however, very wonderful and peculiarly Turneresque; the sky is also beautiful in form, and the foreground, in which we find his old regard for washerwomen has not quite deserted him, singularly skillful. It is curious how formal the whole picture becomes if this figure and the gray stones beside it are hidden with the hand.