полная версия

полная версияThe Harbours of England

It is very interesting to note how repugnant every oceanic idea appears to be to the whole nature of our principal English mediæval poet, Chaucer. Read first the Man of Lawe's Tale, in which the Lady Constance is continually floated up and down the Mediterranean, and the German Ocean, in a ship by herself; carried from Syria all the way to Northumberland, and there wrecked upon the coast; thence yet again driven up and down among the waves for five years, she and her child; and yet, all this while, Chaucer does not let fall a single word descriptive of the sea, or express any emotion whatever about it, or about the ship. He simply tells us the lady sailed here and was wrecked there; but neither he nor his audience appear to be capable of receiving any sensation, but one of simple aversion, from waves, ships, or sands. Compare with his absolutely apathetic recital, the description by a modern poet of the sailing of a vessel, charged with the fate of another Constance:

"It curled not Tweed alone, that breeze—For far upon Northumbrian seasIt freshly blew, and strong;Where from high Whitby's cloistered pile,Bound to St. Cuthbert's holy isle,It bore a bark along.Upon the gale she stooped her side,And bounded o'er the swelling tideAs she were dancing home.The merry seamen laughed to seeTheir gallant ship so lustilyFurrow the green sea foam."Now just as Scott enjoys this sea breeze, so does Chaucer the soft air of the woods; the moment the older poet lands, he is himself again, his poverty of language in speaking of the ship is not because he despises description, but because he has nothing to describe. Hear him upon the ground in Spring:

"These woodes else recoveren greene,That drie in winter ben to sene,And the erth waxeth proud withall,For sweet dewes that on it fall,And the poore estate forget,In which that winter had it set:And then becomes the ground so proude,That it wol have a newe shroude,And maketh so queint his robe and faire,That it had hewes an hundred paire,Of grasse and floures, of Inde and Pers,And many hewes full divers:That is the robe I mean ywisThrough which the ground to praisen is."In like manner, wherever throughout his poems we find Chaucer enthusiastic, it is on a sunny day in the "good green-wood," but the slightest approach to the sea-shore makes him shiver; and his antipathy finds at last positive expression, and becomes the principal foundation of the Frankeleine's Tale, in which a lady, waiting for her husband's return in a castle by the sea, behaves and expresses herself as follows:—

"Another time wold she sit and thinke,And cast her eyen dounward fro the brinke;But whan she saw the grisly rockes blake,For veray fere so wold hire herte quakeThat on hire feet she might hire not susteneThan wold she sit adoun upon the grene,And pitously into the see behold,And say right thus, with careful sighes cold.'Eterne God, that thurgh thy purveanceLedest this world by certain governance,In idel, as men sain, ye nothing make.But, lord, thise grisly fendly rockes blake,That semen rather a foule confusionOf werk, than any faire creationOf swiche a parfit wise God and stable,Why han ye wrought this werk unresonable?'"The desire to have the rocks out of her way is indeed severely punished in the sequel of the tale; but it is not the less characteristic of the age, and well worth meditating upon, in comparison with the feelings of an unsophisticated modern French or English girl among the black rocks of Dieppe or Ramsgate.

On the other hand, much might be said about that peculiar love of green fields and birds in the Middle Ages; and of all with which it is connected, purity and health in manners and heart, as opposed to the too frequent condition of the modern mind—

"As for the birds in the thicket,Thrush or ousel in leafy niche,Linnet or finch—she was far too richTo care for a morning concert to whichShe was welcome, without a ticket."13But this would lead us far afield, and the main fact I have to point out to the reader is the transition of human grace and strength from the exercises of the land to those of the sea in the course of the last three centuries.

Down to Elizabeth's time chivalry lasted; and grace of dress and mien, and all else that was connected with chivalry. Then came the ages which, when they have taken their due place in the depths of the past, will be, by a wise and clear-sighted futurity, perhaps well comprehended under a common name, as the ages of Starch; periods of general stiffening and bluish-whitening, with a prevailing washerwoman's taste in everything; involving a change of steel armor into cambric; of natural hair into peruke; of natural walking into that which will disarrange no wristbands; of plain language into quips and embroideries; and of human life in general, from a green race-course, where to be defeated was at worst only to fall behind and recover breath, into a slippery pole, to be climbed with toil and contortion, and in clinging to which, each man's foot is on his neighbor's head.

But, meanwhile, the marine deities were incorruptible. It was not possible to starch the sea; and precisely as the stiffness fastened upon men, it vanished from ships. What had once been a mere raft, with rows of formal benches, pushed along by laborious flap of oars, and with infinite fluttering of flags and swelling of poops above, gradually began to lean more heavily into the deep water, to sustain a gloomy weight of guns, to draw back its spider-like feebleness of limb, and open its bosom to the wind, and finally darkened down from all its painted vanities into the long, low hull, familiar with the overflying foam; that has no other pride but in its daily duty and victory; while, through all these changes, it gained continually in grace, strength, audacity, and beauty, until at last it has reached such a pitch of all these, that there is not, except the very loveliest creatures of the living world, anything in nature so absolutely notable, bewitching, and, according to its means and measure, heart-occupying, as a well-handled ship under sail in a stormy day. Any ship, from lowest to proudest, has due place in that architecture of the sea; beautiful, not so much in this or that piece of it, as in the unity of all, from cottage to cathedral, into their great buoyant dynasty. Yet, among them, the fisher-boat, corresponding to the cottage on the land (only far more sublime than a cottage ever can be), is on the whole the thing most venerable. I doubt if ever academic grove were half so fit for profitable meditation as the little strip of shingle between two black, steep, overhanging sides of stranded fishing-boats. The clear, heavy water-edge of ocean rising and falling close to their bows, in that unaccountable way which the sea has always in calm weather, turning the pebbles over and over as if with a rake, to look for something, and then stopping a moment down at the bottom of the bank, and coming up again with a little run and clash, throwing a foot's depth of salt crystal in an instant between you and the round stone you were going to take in your hand; sighing, all the while, as if it would infinitely rather be doing something else. And the dark flanks of the fishing-boats all aslope above, in their shining quietness, hot in the morning sun, rusty and seamed with square patches of plank nailed over their rents; just rough enough to let the little flat-footed fisher-children haul or twist themselves up to the gunwales, and drop back again along some stray rope; just round enough to remind us, in their broad and gradual curves, of the sweep of the green surges they know so well, and of the hours when those old sides of seared timber, all ashine with the sea, plunge and dip into the deep green purity of the mounded waves more joyfully than a deer lies down among the grass of spring, the soft white cloud of foam opening momentarily at the bows, and fading or flying high into the breeze where the sea-gulls toss and shriek,—the joy and beauty of it, all the while, so mingled with the sense of unfathomable danger, and the human effort and sorrow going on perpetually from age to age, waves rolling forever, and winds moaning forever, and faithful hearts trusting and sickening forever, and brave lives dashed away about the rattling beach like weeds forever; and still at the helm of every lonely boat, through starless night and hopeless dawn, His hand, who spread the fisher's net over the dust of the Sidonian palaces, and gave into the fisher's hand the keys of the kingdom of heaven.

Next after the fishing-boat—which, as I said, in the architecture of the sea represents the cottage, more especially the pastoral or agricultural cottage, watchful over some pathless domain of moorland or arable, as the fishing-boat swims, humbly in the midst of the broad green fields and hills of ocean, out of which it has to win such fruit as they can give, and to compass with net or drag such flocks as it may find,—next to this ocean-cottage ranks in interest, it seems to me, the small, over-wrought, under-crewed, ill-caulked merchant brig or schooner; the kind of ship which first shows its couple of thin masts over the low fields or marshes as we near any third-rate sea-port; and which is sure somewhere to stud the great space of glittering water, seen from any sea-cliff, with its four or five square-set sails. Of the larger and more polite tribes of merchant vessels, three-masted, and passenger-carrying, I have nothing to say, feeling in general little sympathy with people who want to go anywhere; nor caring much about anything, which in the essence of it expresses a desire to get to other sides of the world; but only for homely and stay-at-home ships, that live their life and die their death about English rocks. Neither have I any interest in the higher branches of commerce, such as traffic with spice islands, and porterage of painted tea-chests or carved ivory; for all this seems to me to fall under the head of commerce of the drawing-room; costly, but not venerable. I respect in the merchant service only those ships that carry coals, herrings, salt, timber, iron, and such other commodities, and that have disagreeable odor, and unwashed decks. But there are few things more impressive to me than one of these ships lying up against some lonely quay in a black sea-fog, with the furrow traced under its tawny keel far in the harbor slime. The noble misery that there is in it, the might of its rent and strained unseemliness, its wave-worn melancholy, resting there for a little while in the comfortless ebb, unpitied, and claiming no pity; still less honored, least of all conscious of any claim to honor; casting and craning by due balance whatever is in its hold up to the pier, in quiet truth of time; spinning of wheel, and slackening of rope, and swinging of spade, in as accurate cadence as a waltz music; one or two of its crew, perhaps, away forward, and a hungry boy and yelping dog eagerly interested in something from which a blue dull smoke rises out of pot or pan; but dark-browed and silent, their limbs slack, like the ropes above them, entangled as they are in those inextricable meshes about the patched knots and heaps of ill-reefed sable sail. What a majestic sense of service in all that languor! the rest of human limbs and hearts, at utter need, not in sweet meadows or soft air, but in harbor slime and biting fog; so drawing their breath once more, to go out again, without lament, from between the two skeletons of pier-heads, vocal with wash of under wave, into the gray troughs of tumbling brine; there, as they can, with slacked rope, and patched sail, and leaky hull, again to roll and stagger far away amidst the wind and salt sleet, from dawn to dusk and dusk to dawn, winning day by day their daily bread; and for last reward, when their old hands, on some winter night, lose feeling along the frozen ropes, and their old eyes miss mark of the lighthouse quenched in foam, the so-long impossible Rest, that shall hunger no more, neither thirst any more,—their eyes and mouths filled with the brown sea-sand.

After these most venerable, to my mind, of all ships, properly so styled, I find nothing of comparable interest in any floating fabric until we come to the great achievement of the 19th century. For one thing this century will in after ages be considered to have done in a superb manner, and one thing, I think, only. It has not distinguished itself in political spheres; still less in artistical. It has produced no golden age by its Reason; neither does it appear eminent for the constancy of its Faith. Its telescopes and telegraphs would be creditable to it, if it had not in their pursuit forgotten in great part how to see clearly with its eyes, and to talk honestly with its tongue. Its natural history might have been creditable to it also, if it could have conquered its habit of considering natural history to be mainly the art of writing Latin names on white tickets. But, as it is, none of these things will be hereafter considered to have been got on with by us as well as might be; whereas it will always be said of us, with unabated reverence,

"they built ships of the line."

Take it all in all, a Ship of the Line is the most honorable thing that man, as a gregarious animal, has ever produced. By himself, unhelped, he can do better things than ships of the line; he can make poems and pictures, and other such concentrations of what is best in him. But as a being living in flocks, and hammering out, with alternate strokes and mutual agreement, what is necessary for him in those flocks, to get or produce, the ship of the line is his first work. Into that he has put as much of his human patience, common sense, forethought, experimental philosophy, self-control, habits of order and obedience, thoroughly wrought handwork, defiance of brute elements, careless courage, careful patriotism, and calm expectation of the judgment of God, as can well be put into a space of 300 feet long by 80 broad. And I am thankful to have lived in an age when I could see this thing so done.

Considering, then, our shipping, under the three principal types of fishing-boat, collier, and ship of the line, as the great glory of this age; and the "New Forest" of mast and yard that follows the windings of the Thames, to be, take it all in all, a more majestic scene, I don't say merely than any of our streets or palaces as they now are, but even than the best that streets and palaces can generally be; it has often been a matter of serious thought to me how far this chiefly substantial thing done by the nation ought to be represented by the art of the nation; how far our great artists ought seriously to devote themselves to such perfect painting of our ships as should reveal to later generations—lost perhaps in clouds of steam and floating troughs of ashes—the aspect of an ancient ship of battle under sail.

To which, I fear, the answer must be sternly this: That no great art ever was, or can be, employed in the careful imitation of the work of man as its principal subject. That is to say, art will not bear to be reduplicated. A ship is a noble thing, and a cathedral a noble thing, but a painted ship or a painted cathedral is not a noble thing. Art which reduplicates art is necessarily second-rate art. I know no principle more irrefragably authoritative than that which I had long ago occasion to express: "All noble art is the expression of man's delight in God's work; not in his own."

"How!" it will be asked, "Are Stanfield, Isabey, and Prout necessarily artists of the second order because they paint ships and buildings instead of trees and clouds?" Yes, necessarily of the second order; so far as they paint ships rather than sea, and so far as they paint buildings rather than the natural light, and color, and work of years upon those buildings. For, in this respect, a ruined building is a noble subject, just as far as man's work has therein been subdued by nature's; and Stanfield's chief dignity is his being a painter less of shipping than of the seal of time or decay upon shipping.14 For a wrecked ship, or shattered boat, is a noble subject, while a ship in full sail, or a perfect boat, is an ignoble one; not merely because the one is by reason of its ruin more picturesque than the other, but because it is a nobler act in man to meditate upon Fate as it conquers his work, than upon that work itself.

Shipping, therefore, in its perfection, never can become the subject of noble art; and that just because to represent it in its perfection would tax the powers of art to the utmost. If a great painter could rest in drawing a ship, as he can rest in drawing a piece of drapery, we might sometimes see vessels introduced by the noblest workmen, and treated by them with as much delight as they would show in scattering luster over an embroidered dress, or knitting the links of a coat of mail. But ships cannot be drawn at times of rest. More complicated in their anatomy than the human frame itself, so far as that frame is outwardly discernible; liable to all kinds of strange accidental variety in position and movement, yet in each position subject to imperative laws which can only be followed by unerring knowledge; and involving, in the roundings and foldings of sail and hull, delicacies of drawing greater than exist in any other inorganic object, except perhaps a snow wreath,15 —they present, irrespective of sea or sky, or anything else around them, difficulties which could only be vanquished by draughtsmanship quite accomplished enough to render even the subtlest lines of the human face and form. But the artist who has once attained such skill as this will not devote it to the drawing of ships. He who can paint the face of St. Paul will not elaborate the parting timbers of the vessel in which he is wrecked; and he who can represent the astonishment of the apostles at the miraculous draught will not be solicitous about accurately showing that their boat is overloaded.

"What!" it will perhaps be replied, "have, then, ships never been painted perfectly yet, even by the men who have devoted most attention to them?" Assuredly not. A ship never yet has been painted at all, in any other sense than men have been painted in "Landscapes with figures." Things have been painted which have a general effect of ships, just as things have been painted which have a general effect of shepherds or banditti; but the best average ship-painting no more reaches the truth of ships than the equestrian troops in one of Van der Meulen's battle-pieces express the higher truths of humanity.

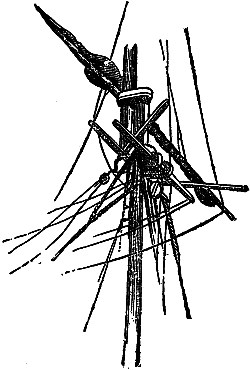

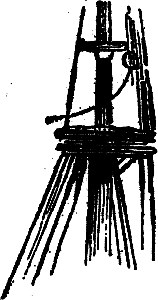

Fig. 1

Fig. 2.

Take a single instance. I do not know any work in which, on the whole, there is a more unaffected love of ships for their own sake, and a fresher feeling of sea breeze always blowing, than Stanfield's "Coast Scenery." Now, let the reader take up that book, and look through all the plates of it at the way in which the most important parts of a ship's skeleton are drawn, those most wonderful junctions of mast with mast, corresponding to the knee or hip in the human frame, technically known as "Tops." Under its very simplest form, in one of those poor collier brigs, which I have above endeavored to recommend to the readers affection, the junction of the top-gallant-mast with the topmast, when the sail is reefed, will present itself under no less complex and mysterious form than this in Fig. 1, a horned knot of seven separate pieces of timber, irrespective of the two masts and the yard; the whole balanced and involved in an apparently inextricable web of chain and rope, consisting of at least sixteen ropes about the top-gallant-mast, and some twenty-five crossing each other in every imaginable degree of slackness and slope about the topmast. Two-thirds of these ropes are omitted in the cut, because I could not draw them without taking more time and pains than the point to be illustrated was worth; the thing, as it is, being drawn quite well enough to give some idea of the facts of it. Well, take up Stanfield's "Coast Scenery," and look through it in search of tops, and you will invariably find them represented as in Fig. 2, or even with fewer lines; the example Fig. 2 being one of the tops of the frigate running into Portsmouth harbor, magnified to about twice its size in the plate.

"Well, but it was impossible to do more on so small a scale." By no means: but take what scale you choose, of Stanfield's or any other marine painter's most elaborate painting, and let me magnify the study of the real top in proportion, and the deficiency of detail will always be found equally great: I mean in the work of the higher artists, for there are of course many efforts at greater accuracy of delineation by those painters of ships who are to the higher marine painter what botanical draughtsmen are to the landscapists; but just as in the botanical engraving the spirit and life of the plant are always lost, so in the technical ship-painting the life of the ship is always lost, without, as far as I can see, attaining, even by this sacrifice, anything like completeness of mechanical delineation. At least, I never saw the ship drawn yet which gave me the slightest idea of the entanglement of real rigging.

Respecting this lower kind of ship-painting, it is always matter of wonder to me that it satisfies sailors. Some years ago I happened to stand longer than pleased my pensioner guide before Turner's "Battle of Trafalgar," at Greenwich Hospital; a picture which, at a moderate estimate, is simply worth all the rest of the hospital—ground—walls—pictures and models put together. My guide, supposing me to be detained by indignant wonder at seeing it in so good a place, assented to my supposed, sentiments by muttering in a low voice: "Well, sir, it is a shame that that thing should be there. We ought to 'a 'ad a Uggins; that's sartain." I was not surprised that my sailor friend should be disgusted at seeing the Victory lifted nearly right out of the water, and all the sails of the fleet blowing about to that extent that the crews might as well have tried to reef as many thunder-clouds. But I was surprised at his perfect repose of respectful faith in "Uggins," who appeared to me—unfortunate landsman as I was—to give no more idea of the look of a ship of the line going through the sea, than might be obtained from seeing one of the correct models at the top of the hall floated in a fishpond.

Leaving, however, the sailor to his enjoyment, on such grounds as it may be, of this model drawing, and being prepared to find only a vague and hasty shadowing forth of shipping in the works of artists proper, we will glance briefly at the different stages of excellence which such shadowing forth has reached, and note in their consecutive changes the feelings with which shipping has been regarded at different periods of art.

1. Mediæval Period. The vessel is regarded merely as a sort of sea-carriage, and painted only so far as it is necessary for complete display of the groups of soldiers or saints on the deck: a great deal of quaint shipping, richly hung with shields, and gorgeous with banners, is, however, thus incidently represented in 15th-century manuscripts, embedded in curly green waves of sea full of long fish; and although there is never the slightest expression of real sea character, of motion, gloom, or spray, there is more real interest of marine detail and incident than in many later compositions.

2. Early Venetian Period. A great deal of tolerably careful boat-drawing occurs in the pictures of Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini, deserving separate mention among the marine schools, in confirmation of what has been stated above, that the drawing of boats is more difficult than that of the human form. For, long after all the perspectives and fore-shortenings of the human body were completely understood, as well as those of architecture, it remained utterly beyond the power of the artists of the time to draw a boat with even tolerable truth. Boats are always tilted up on end, or too long, or too short, or too high in the water. Generally they appear to be regarded with no interest whatever, and are painted merely where they are matters of necessity. This is perfectly natural: we pronounce that there is romance in the Venetian conveyance by oars, merely because we ourselves are in the habit of being dragged by horses. A Venetian, on the other hand, sees vulgarity in a gondola, and thinks the only true romance is in a hackney coach. And thus, it was no more likely that a painter in the days of Venetian power should pay much attention to the shipping in the Grand Canal than that an English artist should at present concentrate the brightest rays of his genius on a cab-stand.