полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

It is rather curious that the mode of bird-catching which is familiar to us under the name of bat-fowling is employed in the East. The fowlers supply themselves with a large net supported on two sticks, and, taking a lantern with them fastened to the top of a pole, they sally out at night to the places where the small birds sleep.

Raising the net on its sticks, they lift it to the requisite height, and hold the lantern exactly opposite to it, so as to place the net between the birds and the lantern. The roosting-places are then beaten with sticks or pelted with stones, so as to awaken the sleeping birds. Startled by the sudden noise, they dash from their roosts, instinctively make towards the light, and so fall into the net. Bird-catching with nets is several times mentioned in the Old Testament, but in the New the net is only alluded to as used for taking fish.

Beside the net, several other modes of bird-catching were used by the ancient Jews, just as is the case at the present day. Boys, for example, who catch birds for their own consumption, and not for the market, can do so by means of various traps, most of which are made on the principle of the noose, or snare. Sometimes a great number of hair-nooses are set in places to which the birds are decoyed, so that in hopping about many of them are sure to become entangled in the snares. Sometimes the noose is ingeniously suspended in a narrow passage which the birds are likely to traverse, and sometimes a simple fall-trap is employed.

To these nooses many allusions are made in the Scriptures. See, for example, Ps. cxxiv. 7: "Our soul is escaped as a bird (tzippor) out of the snare of the fowlers: the snare is broken, and we are escaped." Also Prov. vii. 23: "He goeth after her straightway, as an ox goeth to the slaughter … as a bird hasteneth to the snare, and knoweth not that it is for his life." There is one passage in Ecclesiastes, where both the fishing-net and the snare are mentioned in connexion with each other: "For man knoweth not his time: as the fishes that are taken in an evil net, and as the birds that are caught in the snare; so are the sons of men snared in an evil time, when it falleth suddenly upon them" (ix. 12).

Allusion is also made to the snare by the prophet Amos in one of the passages where his rough, homely diction rises by successive steps into sublimity: "Can a bird fall in a snare upon the earth, where no gin is for him? shall one take up a snare from the earth, and have taken nothing at all?" (iii. 5.)

So common was the use of the snare that it was frequently used as a familiar image by the sacred writers. "How long shall this man be a snare to us?" said Pharaoh's servants of Moses, through whom the waters of the sacred river had been polluted, and various other plagues had come upon the Egyptians. Idols are called snares in many parts of the Scriptures, and so is the society of the wicked. A forcible use of this image was made by Saul when he found that his daughter Michal loved David: "And Saul said, I will give him her, that she may be a snare to him, and that the hand of the Philistines may be against him" (1 Sam. xviii. 21). His device, or snare, not only failed, but, as we learn in the succeeding chapter, verses 11-16, David was "delivered from the snare of the fowler," by the very means which had been employed for entrapping him.

We now pass to another division of the subject. In Ps. lxxxiv. 1-3, we come upon a passage in which the Sparrow is again mentioned: "How amiable are Thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts!

"My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord; my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.

"Yea, the sparrow hath found an house, and the swallow a nest for herself, where she may lay her young, even Thine altars, O Lord of hosts, my King, and my God."

It is evident that we have in this passage a different bird from the Sparrow that sitteth alone upon the house-tops; and though the same word, tzippor, is used in both cases, it is clear that whereas the former bird was mentioned as an emblem of sorrow, solitude, and sadness, the latter is brought forward as an image of joy and happiness. "Blessed are they," proceeds the Psalmist, "that dwell in Thy house: they will be still praising Thee.... For a day in Thy courts is better than a thousand. I had rather be a doorkeeper in the house of my God, than to dwell in the tents of wickedness."

According to Mr. Tristram, this is probably one of the species to which allusion is made by the Psalmist. While inspecting the ruins in the neighbourhood of the Temple, he came upon an old wall. "Near this gate I climbed on to the top of the wall, and walked along for some time, enjoying the fine view at the gorge of the Kedron, with its harvest crop of little white tombs. In a chink I discovered a sparrow's nest (Passer cisalpinus, var.) of a species so closely allied to our own that it is difficult to distinguish it, one of the very kind of which the Psalmist sung.... The swallows had departed for the winter, but the sparrow has remained pertinaciously through all the sieges and changes of Jerusalem."

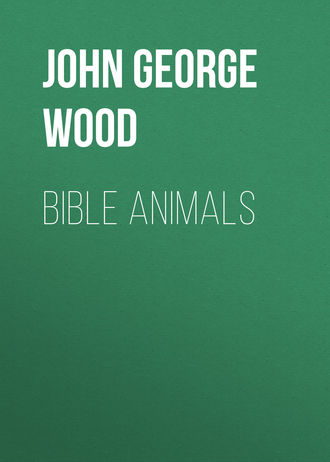

THE TREE-SPARROW, OR SPARROW OF SCRIPTURE.

"Yea, the sparrow hath found an house, where she may lay her young."—Ps. lxxxiv. 3.

The same traveller thinks that the Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) may be the species to which the sacred writer refers, as it is even now very plentiful about the neighbourhood of the Temple. In all probability we may accept both these birds as representatives of the Sparrow which found a home in the Temple. The swallow is separately mentioned, possibly because its migratory habits rendered it a peculiarly conspicuous bird; but it is probable that many species of birds might make their nests in a place where they felt themselves secure from disturbance, and that all these birds would be mentioned under the collective and convenient term of Tzipporim.

As we are engaged upon the word Sparrow, it may be mentioned that several species of Sparrow inhabit Palestine. There is, for example, the common House Sparrow, with which we are so familiar. Then, as has just been described, there is the Tree Sparrow—a bird which is very common in some parts of England, and never seen in others.

Beside these, there is the Marsh Sparrow, or Spanish Sparrow (Passer salicarius), which haunts the banks of the Jordan, and is found there in countless myriads. Mr. Tristram mentions that it builds so plentifully in the thorn-bushes of the Jordan valley, that he has seen the branches borne down by the weight of the nests. The same writer, in remarking upon the difficulty, not to say impossibility, of defining the precise bird which was signified by a Hebrew word, says that, exclusive of the crow tribe, the swifts, cuckoos, rollers, kingfishers, &c., nearly one hundred and fifty species of passerine birds are known to inhabit the Holy Land, any or all of which may be signified by the word tzippor.

In curious contrast to the generally unobservant nature of the Oriental, and to the almost entire absence in Scripture of any allusion to the song of birds, we find that not only do the Orientals of the present day keep singing-birds in cages, but that the custom was in all probability prevalent during the days when the various Scriptural books were written. Any of my readers who are familiar—as they ought to be—with that store-house of Oriental manners, the "Arabian Nights," will remember several allusions to birds kept in cages, some for their song, some for their beauty of plumage, and some for their powers of talking. The same custom is continued at the present day; and not only in Palestine, but in other Eastern countries, birds may be seen in cages hung outside the houses.

In two passages of the Scriptures the word "cage" is mentioned, but in one case the word evidently has another meaning, and in the other the signification is open to doubt.

The first of these passages occurs in Jer. v. 27: "For among my people are found wicked men: they lay wait, as he that setteth snares; they set a trap, they catch men.

"As a cage is full of birds, so are their houses full of deceit."

There is but little doubt that the word which is rendered here as "cage" really signifies a trap, probably one of the basket-traps which are still employed in the East in bird-catching. One marginal reading gives the word as "coop." The whole of the context, however, shows that reference is made, not to keeping birds in cages, but to capturing them in traps, to which the houses of the wicked are compared.

The second mention of the word "cage" occurs in the Revelation, where the sacred writer compares Babylon with "a cage of every unclean bird." The word in this case signifies "prison," and we cannot definitely say that it represents a cage such as we understand by the word. There is, however, a passage in the Book of Job (xli. 5) which unmistakeably alludes to the custom of domesticating birds. Speaking of the leviathan and its strength, the sacred writer uses the following metaphor:—"Wilt thou play with him as with a bird, or wilt thou bind him for thy maidens?"

THE CUCKOO

The Cuckoo only twice mentioned in Scripture—Difficulty of identifying the Shachaph—The common species, and the Great Spotted Cuckoo—Depositing the egg—Conjectures respecting the Shachaph—Etymology of the word—The various gulls, and other sea-birds.

Only in two instances is the word Cuckoo found in the Authorized Version of the Bible, and as they occur in parallel passages they are practically reduced to one. In Lev. xi. 16 we find it mentioned among the birds that might not be eaten, and the same prohibition is repeated in Deut. xiv. 15, the Jews being ordered to hold the bird in abomination.

The Hebrew word is shachaph (the vowels to be pronounced as in "mat"), but as to the precise bird which is signified we can but conjecture. The etymology of the word gives us but little assistance. Shachaph is derived from a root that signifies leanness or slenderness; but it is not very easy to base an interpretation on such grounds. In the Jewish Bible the word is rendered as "Cuckoo," but with the addition of the doubtful mark.

It is possible that the bird may be the Shachaph of the Pentateuch, for several species of Cuckoo are known to inhabit the Holy Land. One of them is the species with which we are so familiar in this country by sound, if not by sight, and which possesses in Palestine the same habits as in England. It is rather remarkable, by the way, that the Arabic name for the bird is exactly the same as ours, the peculiar cry having supplied the name. Its habit of laying its eggs in the nests of other birds is well known, together with the curious fact, that although so large a bird, measuring more than a foot in length, its egg is not larger than that of the little birds, such as the hedge-sparrow, robin, or redstart.

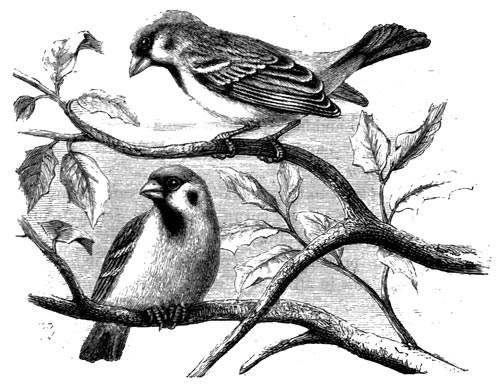

THE GREAT SPOTTED CUCKOO.

"And the owl, and the night-hawk, and the cuckoo, and the hawk after his kind."—Lev. xi. 16; Deut. xiv. 15.

Besides this species, another Cuckoo inhabits Palestine, and is much more common. This is the Great Spotted Cuckoo (Oxylophus glandarius). The birds belonging to this genus have been separated from the other Cuckoos because the feathers on the head are formed into a bold crest, in some species, such as Le Vaillant's Cuckoo, reminding the observer of the crest of the cockatoo. This fine bird measures nearly sixteen inches in length, and can be distinguished, not only by the crested head, but by the reddish grey of the throat and chest, and the white tips of the wing and tail feathers.

This species lays its eggs in the nests of comparatively large birds, such as the rooks, crows, and magpies; and it is a remarkable fact, that just as the egg of the English Cuckoo is very small, so as to suit the nests of the little birds in which it is placed, that of the Great Spotted Cuckoo is as large as the average rook's egg, so as to be in proportion to the nests of the larger birds.

Many commentators believe that by the word shachaph was signified some species of sea-gull, or at all events some marine bird. As such birds live on fish, they would necessarily come into the class of unclean birds, and there is on that account some probability that the suggestion is a correct one.

Dr. Lewysohn has a very elaborate disquisition on the subject, in which he decides that the creature was one of the sea-birds, and derives its name of Shachaph, or "attenuated," from the meagreness of its proportions. Of the various sea-birds, he selects the petrel as the species which he thinks to have been signified by the word. This bird, as he says, is a very lean one, having many feathers, but very little flesh, so that its limbs are no larger than olives, and no one could make a meal of it. This last remark, however, tends to diminish rather than to establish his theory, as, if the bird could not be eaten, there would have been no object in prohibiting the Jews from eating it.

He further proceeds to observe that the bird is unable to scratch, and may therefore be given to a child as a playfellow, and that it is capable of being domesticated and living in a cage. There is, however, no argument here, and the theory is not a tenable one.

Mr. Tristram, with far more probability, suggests that if the bird be not one of the Cuckoos, and be really a sea-bird, it may be one of the shearwaters which live in such numbers on the sea-shore of Palestine. He mentions especially two species, the Great Shearwater (Puffinus cinereus) and the Manx Shearwater (Puffinus anglorum), both of which are extremely plentiful on the coast, skimming continually over the water, and being at the present day regarded by the Mahometans with superstitious awe, being thought to be the ever-restless souls of the condemned, who are doomed to fly backwards and forwards continually until the end of the world, clad in sombre plumage, and never permitted to rest.

Besides the shearwater, many species of gull inhabit the same coast, and it is not at all unlikely that the word shachaph was used in a collective sense, as we have seen to be the case with tzippor, and signified any of the marine birds, without aiming at distinction of species.

THE DOVE

Parallel between the lamb and the Dove—Derivation of the Hebrew word Yonâh—The Dove and the olive branch—Abram's sacrifice, and its acceptance—The sacrifice according to the law of Moses—The Dove-sellers of the Temple—Talmudical zoology—The story of Ilisch—The Dove and the raven—The Dove a type of Israel—The Beni-yonâh, or Sons of Pigeons—Home-finding instinct of the pigeon—The Oriental Dove-cotes—Voice of the Dove—Its strength of wing—The Dove's dung of Samaria—Various pigeons of Palestine—The Rock-Dove and its multitudes—The Dove and the Griffon—The Turtle-Doves of Palestine, and their appearance and habits.

In giving the Scriptural history of the Doves and Pigeons, we shall find ourselves rather perplexed in compressing the needful information into a reasonable space. There is no bird which plays a more important part, both in the Old and the New Testaments, or which is employed so largely in metaphor and symbol.

The Doves and Pigeons were to the birds what were the sheep and lambs to the animals, and, like them, derived their chief interest from their use in sacrifice. Both the lamb and the young pigeon being emblems of innocence, both were used on similar occasions, the latter being in many instances permitted when the former were too expensive for the means of the offerer. As to the rendering of the Hebrew words which have been translated as Pigeon, Dove, and Turtle Dove, there has never been any discussion. The Hebrew word yonâh has always been acknowledged to signify the Dove or Pigeon, and the word tôr to signify the Turtle Dove. Generally, the two words are used in combination, so that tor-yonâh signifies the Turtle Dove.

Though the interpretation of the word yonâh is universally accepted, there is a little difficulty about its derivation, and its signification apart from the bird. Some have thought that it is derived from a root signifying warmth, in allusion to the warmth of its affection, the Dove having from time immemorial been selected as the type of conjugal love. Others, among whom is Buxtorf, derive it from a word which signifies oppression, because the gentle nature of the Dove, together with its inability to defend itself, cause it to be oppressed, not only by man, but by many rapacious birds.

The first passage in which we hear of the Dove occurs in the earlier part of Genesis. Indeed, the Dove and the raven are the first two creatures that are mentioned by any definite names, the word nachosh, which is translated as "serpent" in Gen. iii. 1, being a collective word signifying any kind of serpent, whether venomous or otherwise, and not used for the purpose of designating any particular species.

Turning to Gen. viii. 8, we come to the first mention of the Dove. The whole passage is too familiar to need quoting, and it is only needful to say that the Dove was sent out of the ark in order that Noah might learn whether the floods had subsided, and that, after she had returned once, he sent her out again seven days afterwards, and that she returned, bearing an olive-branch (or leaf, in the Jewish Bible). Seven days afterwards he sent the Dove for the third time, but she had found rest on the earth, and returned no more.

It is not within the province of this work to treat, except in the most superficial manner, of the metaphorical signification of the Scriptures. I shall, therefore, allude but very slightly to the metaphorical sense of the passages which record the exit from the ark and the sacrifice of Noah. Suffice it to say that, putting entirely aside all metaphor, the characters of the raven and the Dove are well contrasted. The one went out, and, though the trees were at that time submerged, it trusted in its strong wings, and hovered above the watery expanse until the flood had subsided. The Dove, on the contrary, fond of the society of man, and having none of the wild, predatorial habits which distinguish the raven, twice returned to its place of refuge, before it was finally able to find a resting-place for its foot.

After this, we hear nothing of the Dove until the time of Abraham, some four hundred years afterwards, when the covenant was made between the Lord and Abram, when "he believed in the Lord, and it was counted to him for righteousness." In order to ratify this covenant he was ordered to offer a sacrifice, which consisted of a young heifer, a she-goat, a ram, a turtle-dove, and a young dove or pigeon. The larger animals were severed in two, but the birds were not divided, and between the portions of the sacrifice there passed a lamp of fire as a symbol of the Divine presence.

In after days, when the promise that the seed of Abram should be as the stars of heaven for multitude had been amply fulfilled, together with the prophecy that they should be "strangers in a land that was not theirs," and should be in slavery and under oppression for many years, the Dove was specially mentioned in the new law as one of the creatures that were to be sacrificed on certain defined occasions.

Even the particular mode of offering the Dove was strictly defined. See Lev. i. 14-17: "If the burnt sacrifice for his offering to the Lord be of fowls, then he shall bring his offering of turtle-doves, or of young pigeons.

"And the priest shall bring it unto the altar, and wring off his head, and burn it on the altar; and the blood thereof shall be wrung out at the side of the altar.

"And he shall pluck away his crop with his feathers, and cast it beside the altar, on the east part, by the place of the ashes.

"And he shall cleave it with the wings thereof, but shall not divide it asunder: and the priest shall burn it upon the altar, upon the wood that is upon the fire."

Here we have a repetition not only of the sacrifice of Abram, but of the mode in which it was offered, care being taken that the body of the bird should not be divided. There is a slight, though not very important variation in one or two portions of this passage. For example, the wringing off the head of the bird is, literally, pinching off, and had to be done with the thumb nail; and the passage which is by some translators rendered as the crop and the feathers, is by others translated as the crop and its contents—a reading which seems to be more consonant with the usual ceremonial of sacrifice than the other.

As a general rule, the pigeon was only sanctioned as a sacrificial animal in case one of more value could not be afforded; and so much care was taken in this respect, that with the exception of the two "sparrows" (tzipporim) that were enjoined as part of the sacrifice by which the cleansed leper was received back among the people (Lev. xiv. 4), no bird might be offered in sacrifice unless it belonged to the tribe of pigeons.

It was in consequence of the poverty of the family that the Virgin Mary brought two young pigeons when she came to present her new-born Son in the Temple. For those who were able to afford it, the required sacrifice was a lamb of the first year for a burnt-offering, and a young pigeon or Turtle Dove for a sin-offering. But "if she be not able to bring a lamb, then she shall bring two turtles, or two young pigeons, the one for the burnt-offering and the other for a sin-offering." The extraordinary value which all Israelites set upon the first-born son is well known, both parents even changing their own names, and being called respectively the father and mother of Elias, or Joseph, as the case may be. If the parents who had thus attained the summit of their wishes possessed a lamb, or could have obtained one, they would most certainly have offered it in the fulness of their joy, particularly when, as in the case of Mary, there was such cause for rejoicing; and the fact that they were forced to substitute a second pigeon for the lamb is a proof of their extreme poverty.

While the Israelites were comparatively a small and compact nation, dwelling around their tabernacle, the worshippers could easily offer their sacrifices, bringing them from their homes to the altar. But in process of time, when the nation had become a large and scattered one, its members residing at great distances, and only coming to the Temple once or twice in the year to offer their sacrifices, they would have found that for even the poor to carry their pigeons with them would have greatly increased the trouble, and in many cases have been almost impossible.

For the sake of convenience, therefore, a number of dealers established themselves in the outer courts of the Temple, for the purpose of selling Doves to those who came to sacrifice. Sheep and oxen were also sold for the same purpose, and, as offerings of money could only be made in the Jewish coinage, money-changers established themselves for the purpose of exchanging foreign money brought from a distance for the legal Jewish shekel. That these people exceeded their object, and endeavoured to overreach the foreign Jews who were ignorant of the comparative value of money and goods, is evident from the fact of their expulsion by our Lord, and the epithets which were applied to them.

As the Dove played so important a part in the Jewish worship, the Talmudical writers have investigated the subject with a curious minuteness.

In the first place, they discuss the reasons for its selection as the bird of sacrifice, and always endeavour to represent it as contrasted with the raven—all birds of the raven kind, i.e. the rooks, crows, magpies, and the like, being set down as cunning, deceptive, and thieving; while all the pigeon kind are mild, true, and loving. There is a curious story which illustrates this idea. A certain man named Ilisch, who understood the language of birds, was "once upon a time" in captivity, when he heard the cry of a raven, which called out to him, "Ilisch! Ilisch! flee! flee!" But Ilisch said within himself, "I believe not this lying bird." But next came a Dove, which said the same words. Then said Ilisch, "I believe this bird, because Israel is compared to a dove."