полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

In the first place, the word is of very rare occurrence. We only find it three times. It first occurs in Lev. xi. 16, in which it is named, together with the eagle, the ossifrage, and many other birds, as among the unclean creatures, to eat which was an abomination. It is next found in the parallel passage in Deut. xiv. 15, neither of which portions of Scripture need be quoted at length.

That the word netz was used in its collective sense is very evident from the addition which is made to it in both cases. The Hawk, "after its kind," is forbidden, showing therefore that several kinds or species of Hawk were meant. Indeed, any specific detail would be quite needless, as the collective term was quite a sufficient indication, and, having named the vultures, eagles, and larger birds of prey, the simple word netz was considered by the sacred writer as expressing the rest of the birds of prey.

We find the word once more in that part of the Bible to which we usually look for any reference to natural history. In Job xxxix. 26, we have the words, "Doth the hawk fly by thy wisdom, and turn [or stretch] her wings toward the south?" The precise signification of this passage is rather doubtful, but it is generally considered to refer to the migration of several of the Hawk tribe. That the bird in question was distinguished for its power of flight is evident from the fact that the sacred poet has selected that one attribute as the most characteristic of the Netz.

Taking first the typical example of the Hawks, we find that the Sparrow-Hawk (Accipiter nisus) is plentiful in Palestine, finding abundant food in the smaller birds of the country. It selects for its nest just the spots which are so plentiful in the Holy Land, i.e. the crannies of rocks, and the tops of tall trees. Sometimes it builds in deserted ruins, but its favourite spot seems to be the lofty tree-top, and, in default of that, the rock-crevice. It seldom builds a nest of its own, but takes possession of that which has been made by some other bird. Some ornithologists think that it looks out for a convenient nest, say of the crow or magpie, and then ejects the rightful owner. I am inclined to think, however, that it mostly takes possession of a nest that is already deserted, without running the risk of fighting such enemies as a pair of angry magpies. This opinion is strengthened by the fact that the bird resorts to the same nest year after year.

It is a bold and dashing bird, though of no great size, and when wild and free displays a courage which it seems to lose in captivity. As is the case with so many of the birds, the female is much larger than her mate, the latter weighing about six ounces, and measuring about a foot in length, and the former weighing above nine ounces, and measuring about fifteen inches in length.

The most plentiful of the smaller Hawks of Palestine is the Common Kestrel (Tinnunculus alaudarius). This is the same species with which we are so familiar in England under the names of Kestrel, Wind-hover, and Stannel Hawk.

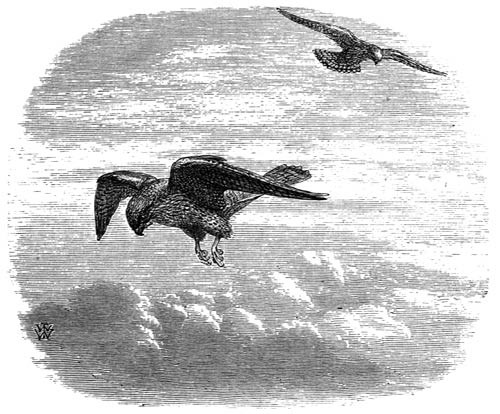

KESTREL.

"Doth the Hawk fly by thy wisdom?"—Job xxxix. 26.

It derives its name of Wind-hover from its remarkable habit of hovering, head to windward, over some spot for many minutes together. This action is always performed at a moderate distance from the ground; some naturalists saying that the Hawk in question never hovers at an elevation exceeding forty feet, while others, myself included, have seen the bird hovering at a height of twice as many yards. Generally, however, it prefers a lower distance, and is able by employing this manœuvre to survey a tolerably large space beneath. As its food consists in a very great measure of field-mice, the Kestrel is thus able by means of its telescopic eyesight to see if a mouse rises from its hole; and if it should do so, the bird drops on it and secures it in its claws.

Unlike the sparrow-hawk, the Kestrel is undoubtedly gregarious, and will build its nest in close proximity to the habitations of other birds, a number of nests being often found within a few yards of each other. Mr. Tristram remarks that he has found its nest in the recesses of the caverns occupied by the griffon vultures, and that the Kestrel also builds close to the eagles, and is the only bird which is permitted to do so. It also builds in company with the jackdaw.

Several species of Kestrel are known, and of them at least two inhabit the Holy Land, the second being a much smaller bird than the Common Kestrel, and feeding almost entirely on insects, which it catches with its claws, the common chafers forming its usual prey. Great numbers of these birds live together, and as they rather affect the society of mankind, they are fond of building their nests in convenient crannies in the mosques or churches. Independently of its smaller size, it may be distinguished from the Common Kestrel by the whiteness of its claws.

The illustration is drawn from a sketch taken from life. The bird hovered so near a house, and remained so long in one place, that the artist fixed a telescope and secured an exact sketch of the bird in the peculiar attitude which it is so fond of assuming. After a while, the Kestrel ascended to a higher elevation, and then resumed its hovering, in the attitude which is shown in the upper figure. In consequence of the great abundance of this species in Palestine, and the peculiarly conspicuous mode of balancing itself in the air while in search of prey, we may feel sure that the sacred writers had it specially in their minds when they used the collective term Netz.

The Kestrel has a very large geographical range, being plentiful not only in England and Palestine, but in Northern and Southern Europe, throughout the greater part of Asia, in Siberia, and in portions of Africa. The bird, therefore, is capable of enduring both heat and cold, and, as is often the case with those creatures that are useful to man, is a perfect cosmopolitan.

It is easily trained, and, although in the old hawking days it was considered a bird which a noble could not carry, it can be trained to chase the smaller birds as successfully as the falcons can be taught to pursue the heron. The name Tinnunculus is supposed by some to have been given to the bird in allusion to its peculiar cry, which is clear, shrill, and consists of a single note several times repeated.

On page 361 the reader may see a representation of a pair of Harier Hawks flying below the rock on which the peregrine falcon has perched, and engaged in pursuing one of the smaller birds.

They have been introduced because several species of Harier are to be found in Palestine, where they take, among the plains and lowlands, the place which is occupied by the other hawks and falcons among the rocks.

The name of Harier appears to be given to these birds on account of their habit of regularly quartering the ground over which they fly when in search of prey, just like hounds when searching for hares. This bird is essentially a haunter of flat and marshy lands, where it finds frogs, mice, lizards, on which it usually feeds. It does not, however, confine itself to such food, but will chase and kill most of the smaller birds, and occasionally will catch even the leveret, the rabbit, the partridge, and the curlew.

When it chases winged prey, it seldom seizes the bird in the air, but almost invariably keeps above it, and gradually drives it to the ground. It will be seen, therefore, that its flight is mostly low, as suits the localities in which it lives, and it seldom soars to any great height, except when it amuses itself by rising and wheeling in circles together with its mate. This proceeding generally takes place before nest-building. The usual flight is a mixture of that of the kestrel and the falcon, the Harier sometimes poising itself over some particular spot, and at others shooting forwards through the air with motionless wings.

Unlike the falcons and most of the hawks, the Harier does not as a rule perch on rocks, but prefers to sit very upright on the ground, perching generally on a mole-hill, stone, or some similar elevation. Even its nest is made on the ground, and is composed of reeds, sedges, sticks, and similar matter, materials that can be procured from marshy land. The nest is always elevated a foot or so from the ground, and has occasionally been found on the top of a mound more than a yard in height. It is, however, conjectured that in such cases the mound is made by one nest being built upon the remains of another. The object of the elevated nest is probably to preserve the eggs in case of a flood.

At least five species of Hariers are known to exist in the Holy Land, two of which are among the British birds, namely, the Marsh Harier (Circus æruginosus), sometimes called the Duck Hawk and the Moor Buzzard, and the Hen Harier (Circus cyaneus), sometimes called the White Hawk, Dove Hawk, or Blue Hawk, on account of the plumage of the male, which differs greatly according to age; and the Ring-tailed Hawk, on account of the dark bars which appear on the tail of the female. All the Hariers are remarkable for the Circlet of feathers that surrounds the eyes, and which resembles in a lesser degree the bold feather-circle around the eye of the owl tribe.

Before taking leave of the Hawks, it is as well to notice the entire absence in the Scriptures of any reference to falconry. Now, seeing that the art of catching birds and animals by means of Hawks is a favourite amusement among Orientals, as has already been mentioned when treating of the gazelle (page 139), and knowing the unchanging character of the East, we cannot but think it remarkable that no reference should be made to this sport in the Scriptures.

It is true that in Palestine itself there would be but little scope for falconry, the rough hilly ground and abundance of cultivated soil rendering such an amusement almost impossible. Besides, the use of the falcon implies that of the horse, and, as we have already seen, the horse was scarcely ever used except for military purposes.

Had, therefore, the experience of the Israelites been confined to Palestine, there would have been good reason for the silence of the sacred writers on this subject. But when we remember that the surrounding country is well adapted for falconry, that the amusement is practised there at the present day, and that the Israelites passed so many years as captives in other countries, we can but wonder that the Hawks should never be mentioned as aids to bird-catching. We find that other bird-catching implements are freely mentioned and employed as familiar symbols, such as the gin, the net, the snare, the trap, and so forth; but that there is not a single passage in which the Hawks are mentioned as employed in falconry.

THE OWL

The words which have been translated as Owl—The Côs, or Little Owl—Use made of the Little Owl in bird-catching—Habits of the bird—The Barn, Screech, or White Owl a native of Palestine—The Yanshûph, or Egyptian Eagle Owl—Its food and nest—The Lilith, or Night Monster—Various interpretations of the word—The Kippoz probably identical with the Scops Owl, or Marouf.

In various parts of the Old Testament there occur several words which are translated as Owl in the Authorized Version, and in most cases the rendering is acknowledged to be the correct one, while in one or two instances there is a difference of opinion on the subject.

In Lev. xi. 16, 17, we find the following birds reckoned among those which are an abomination, and which might not be eaten by the Israelites: "The owl, and the night-hawk, and the cuckoo, and the hawk after his kind;

"And the little owl, and the cormorant, and the great owl."

Here, then, we have in close proximity the word Owl repeated three times, and the same repetition occurs in the parallel passage in Deut. xiv. Now the words which are here translated as Owl are totally different words in the Hebrew, so that if we leave them untranslated, the passages will run as follow: "And the Bath-haya'anah, and the night-hawk, and the cuckoo, and the hawk after his kind;

"And the Côs, and the cormorant, and the Yanshûph."

Taking these words in order, we find in the first place that the Jewish Bible accepts the translation of the words côs and yanshûph, merely affixing to them the mark of doubt. But it translates the word bath-haya'anah as Ostrich, without adding the doubtful mark. Now the same word occurs in several other passages of Scripture, the first being in Job xxx. 29: "I am a brother to dragons, and a companion to owls." In the marginal reading of the Authorized Version, which, as the reader must bear in mind, is of equal value with the text, the rendering is the same as that of the Jewish Bible, and in several other passages the same reading is followed. We therefore accept the word bath-haya'anah as the ostrich, and dismiss it from among the owls.

Coming now to the other words, we find in the passages already quoted the words côs and yanshûph. Both those words occur in other parts of Scripture, and evidently are the names of nocturnal birds that haunt ruins and lonely places. Taking them in order, we find the word côs to occur again in Ps. cii. 6: "I am like a pelican of the wilderness: I am like an owl of the desert." The Psalm in which this passage occurs is a penitential prayer, in which the writer uses many of the metaphors employed by Job when lamenting his afflictions, and describes himself as left alone among men.

The simile is equally just and feasible in this case, the Owl being essentially a bird of night, and associated with solitude and gloom. The particular species which is signified by the word côs bears but very slightly on the subject, inasmuch as in general habits all the true Owls are very similar in hiding by day in their nests, and coming out at night to hunt for prey, their melancholy hoot, or startling shriek, breaking the silence of the night.

Still it is necessary to identify, if we can, some species with the word côs, and it is very likely that the Little Owl, or Boomah of the Arabs (Athene Persica), is the bird which is signified by the word côs. This species is probably identical with the Little Night Owl of England (Athene noctua). Though rare in England, it is very common in many parts of the Continent where it is much valued by bird-catchers, who employ it as a means of attracting small birds to their traps. They place it on the top of a long pole, and carry it into the fields, where they plant the pole in the ground. This Owl has a curious habit of swaying its body backwards and forwards, and is sure to attract the notice of all the small birds in the neighbourhood. It is well known that the smaller birds have a peculiar hatred to the Owl, and never can pass it without mobbing it, assembling in great numbers, and so intent on their occupation that they seem to be incapable of perceiving anything but the object of their hatred. Even rooks, magpies, and hawks are taken by this simple device.

Whether or not the Little Owl was used for this object by the ancient inhabitants of Palestine is rather doubtful; but as they certainly did so employ decoy birds for the purpose of attracting game, it is not unlikely that the Little Owl was found to serve as a decoy. We shall learn more about the system of decoy-birds when we come to the partridge.

THE LITTLE OWL.

"I am like an owl of the desert."—Ps. cii. 6.

The Little Owl is to be found in almost every locality, caring little whether it takes up its residence in cultivated grounds, in villages, among deserted ruins, or in places where man has never lived. As, however, it is protected by the natives, it prefers the neighbourhood of villages, and may be seen quietly perched in some favourite spot, not taking the trouble to move unless it be approached closely. And to detect a perched Owl is not at all an easy matter, as the bird has a way of selecting some spot where the colours of its plumage harmonize so well with the surrounding objects that the large eyes are often the first indication of its presence. Many a time I have gone to search after Owls, and only been made aware of them by the sharp angry snap that they make when startled.

The name Athene, by the way, has been given to this Owl because it is the species selected by the Greeks as the emblem of wisdom.

The common Barn Owl of England (Strix flammea) also inhabits Palestine, and if, as is likely to be the case, the word côs is a collective term under which several species are grouped together, the Barn or White Owl is likely to be one of them.

Like the Little Owl, it affects the neighbourhood of man, though it may be found in ruins and similar localities. An old ruined castle is sure to be tenanted by the Barn Owl, whose nightly shrieks have so often terrified the belated wanderer, and made him fancy that the place was haunted by disturbed spirits. Such being the case in England, it is likely that in the East, where popular superstition has peopled every well with its jinn and every ruin with its spirit, the nocturnal cry of this bird, which is often called the Screech Owl from its note, should be exceedingly terrifying, and would impress itself on the minds of sacred writers as a fit image of solitude, terror, and desolation.

The Screech Owl is scarcely less plentiful in Palestine than the Little Owl, and, whether or not it be mentioned under a separate name, is sure to be one of the birds to which allusion is made in the Scriptures.

Another name now rises before us: this is the Yanshûph, translated as the Great Owl, a word which occurs not only in the prohibitory passages of Leviticus and Deuteronomy, but in the Book of Isaiah. In that book, ch. xxxiv. ver. 10, 11, we find the following passage: "From generation to generation it shall lie waste; none shall pass through it for ever and ever.

"But the cormorant and the bittern shall possess it; the owl (yanshûph) also and the raven shall dwell in it: and He shall stretch out upon it the line of confusion, and the stones of emptiness." The Jewish Bible follows the same reading.

It is most probable that the Great Owl or Yanshûph is the Egyptian Eagle Owl (Bubo ascalaphus), a bird which is closely allied to the great Eagle Owl of Europe (Bubo maximus), and the Virginian Eared Owl (Bubo Virginianus) of America. This fine bird measures some two feet in length, and looks much larger than its real size, owing to the thick coating of feathers which it wears in common with all true Owls, and the ear-like feather tufts on the top of its head, which it can raise or depress at pleasure. Its plumage is light tawny.

This bird has a special predilection for deserted places and ruins, and may at the present time be seen on the very spots of which the prophet spoke in his prediction. It is very plentiful in Egypt, where the vast ruins are the only relics of a creed long passed away or modified into other forms of religion, and its presence only intensifies rather than diminishes the feeling of loneliness that oppresses the traveller as he passes among the ruins.

The European Eagle Owl has all the habits of its Asiatic congener. It dwells in places far from the neighbourhood of man, and during the day is hidden in some deep and dark recess, its enormous eyes not being able to endure the light of day. In the evening it issues from its retreat, and begins its search after prey, which consists of various birds, quadrupeds, reptiles, fish, and even insects when it can find nothing better.

On account of its comparatively large dimensions, it is able to overcome even the full-grown hare and rabbit, while the lamb and the young fawn occasionally fall victims to its voracity. It seems never to chase any creature on the wing, but floats silently through the air, its soft and downy plumage deadening the sound of its progress, and suddenly drops on the unsuspecting prey while it is on the ground.

The nest of this Owl is made in the crevices of rocks, or in ruins, and is a very large one, composed of sticks and twigs, lined with a tolerably large heap of dried herbage, the parent Owls returning to the same spot year after year. Should it not be able to find either a rock or a ruin, it contents itself with a hollow in the ground, and there lays its eggs, which are generally two in number, though occasionally a third egg is found. The Egyptian Eagle Owl does much the same thing, burrowing in sand-banks, and retreating, if it fears danger, into the hollow where its nest has been made.

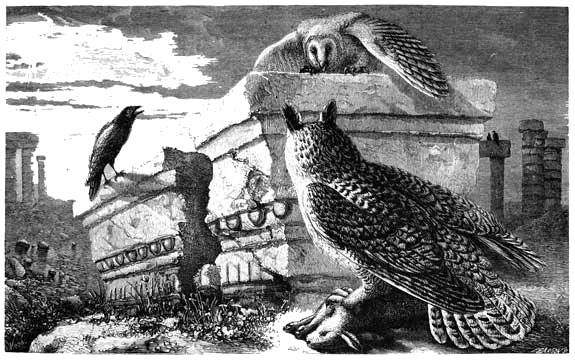

In the large illustration the two last-mentioned species are given. The Egyptian Eagle Owl is seen with its back towards the spectator, grasping in its talons a dead hare, and with ear-tufts erect is looking towards the Barn Owl, which is contemplating in mingled anger and fear the proceedings of the larger bird. Near them is perched a raven, in order to carry out more fully the prophetic words, "the owl also and the raven shall dwell in it."

Two more passages yet remain in which the word Owl is mentioned, and, curiously enough, both of them are found in the Book of Isaiah, the poet-prophet, who seized with a poet's intuition on the natural objects around him, and converted the simplest and most familiar incidents into glowing imagery and powerful metaphor.

If the reader will refer to Isaiah xxxiv. 13-15, he will find the following passages, which are, in fact, a continuation of the prophecy against Idumea, which has already been quoted. "And thorns shall come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof: and it shall be an habitation of dragons, and a court for owls.

"The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest.

"There shall the great owl make her nest, and lay, and hatch, and gather under her shadow."

It has been already mentioned that the word which is translated as Owl, in the first of these passages, is bath-haya'anah, which is generally considered to signify the ostrich. In verse 14 we come to a new word, namely, lilith. In the marginal reading of the Authorized Version, this word is rendered as "night monster," and the Jewish Bible takes nearly the same view of the word by translating it as "a nocturnal one," evidently basing this interpretation upon the derivation of the word. Several Hebraists have thought that the word lilith merely represents some mythological being, like the dread Lamia of the ancients, a mixture of the material and spiritual—too ethereal to be seen by daylight, and too gross to be above the requirements of human food. The blood of mankind was the food of these fearful beings, and, according to old ideas, they could only live among ruins and desert places, where they concealed themselves during the day at the bottoms of wells or the recesses of rock-caverns, and stole out at night to seize on some unlucky wanderer, and suck his blood as he slept.

THE OWL.

"I am a companion to owls."—Job. xxx. 29.

The reader may remember that even our very imperfect version of the "Arabian Nights" repeatedly alludes to this belief, the evil spirit being almost invariably represented as dwelling in ruins, rocky places, and the interiors of wells.

Although it is very possible that the prophet may have referred to some of the mythological beings which were so universally supposed to inhabit deserted spots, and thus to have employed the word lilith as a term which he did not intend to be taken otherwise than metaphorically, it is equally possible that some nocturnal bird may have been meant, and in that case the bird in question must almost certainly have been an Owl of some kind. As to the particular species of Owl, that is a question which cannot be satisfactorily answered, especially as so many scholars find reason to doubt whether the word lilith represents an Owl, or indeed any ordinary inhabitant of earth. As, therefore, we have no data whereon to found a positive opinion, the question will be allowed to remain an open one.