полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

"Pitying its efforts, the falconer throws a handkerchief over its head, and, securing this prize, claims it as his own, declaring that he will bear it home to his house in the mountains, where, after a few weeks' kind treatment and care, it will become as domesticated and affectionate as a spaniel. Meanwhile, Abou Shein gathers together the fallen booty, and, tying them securely with cords, fastens them behind his own saddle, declaring, with a triumphant laugh, that we shall return that evening to the city of Beyrout with such game as few sportsmen can boast of having carried thither in one day."

The gentle nature of the Gazelle is as proverbial as its grace and swiftness, and is well expressed in the large, soft, liquid eye, which has formed from time immemorial the stock comparison of Oriental poets when describing the eyes of beauty.

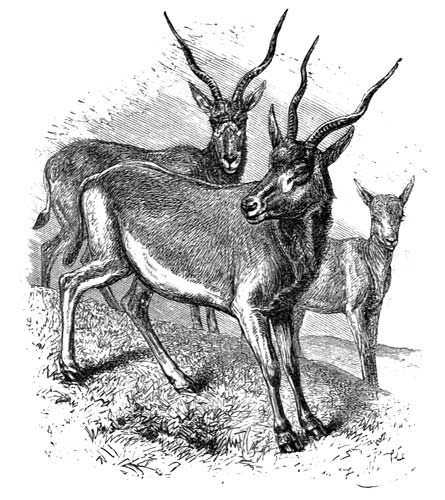

THE PYGARG, OR ADDAX

The Dishon or Dyshon—Signification of the word Pygarg—Certainty that the Dishon is an antelope, and that it must be one of a few species—Former and present range of the Addax—Description of the Addax—The Strepsiceros of Pliny.

There is a species of animal mentioned once in the Scriptures under the name of Dishon which the Jewish Bible leaves untranslated, and merely gives as Dyshon, and which is rendered in the Septuagint by Pugargos, or Pygarg, as one version gives it. Now, the meaning of the word Pygarg is white-crouped, and for that reason the Pygarg of the Scriptures is usually held to be one of the white-crouped antelopes, of which several species are known. Perhaps it may be one of them—it may possibly be neither, and it may probably refer to all of them.

But that an antelope of some kind is meant by the word Dishon is evident enough, and it is also evident that the Dishon must have been one of the antelopes which could be obtained by the Jews. Now as the species of antelope which could have furnished food for that nation are very few in number, it is clear that, even if we do not hit upon the exact species, we may be sure of selecting an animal that was closely allied to it. Moreover, as the nomenclature is exceedingly loose, it is probable that more than one species might have been included in the word Dishon.

Modern commentators have agreed that there is every probability that the Dishon of the Pentateuch was the antelope known by the name of Addax.

This handsome antelope is a native of Northern Africa. It has a very wide range, and, even at the present day, is found in the vicinity of Palestine, so that it evidently was one of the antelopes which could be killed by Jewish hunters. From its large size, and long twisted horns, it bears a strong resemblance to the Koodoo of Southern Africa. The horns, however, are not so long, nor so boldly twisted, the curve being comparatively slight, and not possessing the bold spiral shape which distinguishes those of the koodoo.

THE ADDAX, OR PYGARG OF SCRIPTURE.

"These are the beasts which ye shall eat: the ox, the sheep, … the pygarg, and the wild ox, and the chamois."—Deut. xiv. 4, 5.

The ordinary height of the Addax is three feet seven or eight inches, and the horns are almost exactly alike in the two sexes. Their length, from the head to the tips, is rather more than two feet. Its colour is mostly white, but a thick mane of dark black hair falls from the throat, a patch of similar hair grows on the forehead, and the back and shoulders are greyish brown. There is no mane on the back of the neck, as is the case with the koodoo.

The Addax is a sand-loving animal, as is shown by the wide and spreading hoofs, which afford it a firm footing on the yielding soil. In all probability, this is one of the animals which would be taken, like the wild bull, in a net, being surrounded and driven into the toils by a number of hunters. It is not, however, one of the gregarious species, and is not found in those vast herds in which some of the antelopes love to assemble.

Some writers reject the Addax as the Dishon, and are inclined to consider that the real representative of the word is to be found in the Ariel or Isabella gazelles. Of these, however, we have already treated, and enough has been said about them to show that these gazelles are in all probability comprised under the name Tsebi.

It has been suggested, in contradiction to the opinion that the Dishon is the Addax, that the word Strepsiceros, or Twisted Horn, is given to it by Pliny, who also mentions that one of the native names for the animal is Adas, or Akas, and that he distinguishes it from the Pygarg. Still, the weight of evidence is so great in favour of the identity of the Dishon and the Pygarg, that we may accept the interpretation with safety.

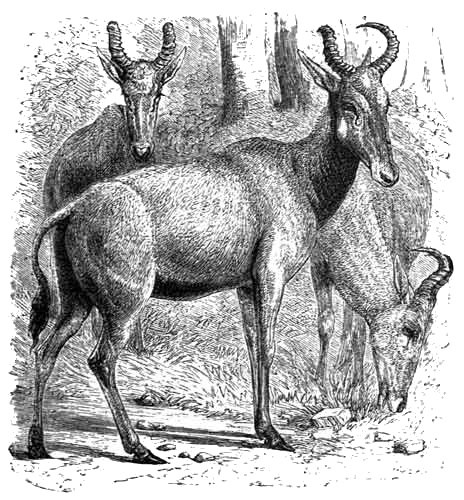

THE FALLOW-DEER, OR BUBALE

The word Jachmur evidently represents a species of antelope—Probability that the Jachmur is identical with the Bubale, or Bekk'r-el-Wash—Resemblance of the animal to the ox tribe—Its ox-like horns and mode of attack—Its capability of domestication—Former and present range of the Bubale—Its representation on the monuments of ancient Egypt—Delicacy of its flesh—Size and general appearance of the animal.

It has already been mentioned that in the Old Testament there occur the names of three or four animals, which clearly belong to one or other of three or four antelopes. Only one of these names now remains to be identified. This is the Jachmur, or Yachmur, a word which has been rendered in the Septuagint as Boubalos, and has been translated in our Authorized Version as Fallow Deer.

We shall presently see that the Fallow Deer is to be identified with another animal, and that the word Jachmur must find another interpretation. If we follow the Septuagint, and call it the Bubale, we shall identify it with a well-known antelope, called by the Arabs the "Bekk'r-el-Wash," and known to zoologists as the Bubale (Acronotus bubalis).

This fine antelope would scarcely be recognised as such by an unskilled observer, as in its general appearance it much more resembles the ox tribe than the antelope. Indeed, the Arabic title, "Bekk'r-el-Wash," or Wild Cow, shows how close must be the resemblance to the oxen. The Arabs, and indeed all the Orientals in whose countries it lives, believe it not to be an antelope, but one of the oxen, and class it accordingly.

How much the appearance of the Bubale justifies them in this opinion may be judged by reference to the figure on page 145. The horns are thick, short, and heavy, and are first inclined forwards, and then rather suddenly bent backwards. This formation of the horns causes the Bubale to use his weapons after the manner of the bull, thereby increasing the resemblance between them. When it attacks, the Bubale lowers its head to the ground, and as soon as its antagonist is within reach, tosses its head violently upwards, or swings it with a sidelong upward blow. In either case, the sharp curved horns, impelled by the powerful neck of the animal, and assisted by the weight of the large head, become most formidable weapons.

It is said that in some places, where the Bubales have learned to endure the presence of man, they will mix with his herds for the sake of feeding with them, and by degrees become so accustomed to the companionship of their domesticated friends, that they live with the herd as if they had belonged to it all their lives. This fact shows that the animal possesses a gentle disposition, and it is said to be as easily tamed as the gazelle itself.

Even at the present day the Bubale has a very wide range, and formerly had in all probability a much wider. It is indigenous to Barbary, and has continued to spread itself over the greater part of Northern Africa, including the borders of the Sahara, the edges of the cultivated districts, and up the Nile for no small distance. In former days it was evidently a tolerably common animal of chase in Upper Egypt, as there are representations of it on the monuments, drawn with the quaint truthfulness which distinguishes the monumental sculpture of that period.

THE BUBALE, OR FALLOW DEER OF SCRIPTURE.

"And Solomon's provision for one day was thirty measures of fine flour, and threescore measure of meal; ten fat oxen, and twenty oxen out of the pastures, and an hundred sheep; beside harts and roebucks, and fallow-deer, and fatted fowl."—1 Kings iv. 22, 23.

It is probable that in and about Palestine it was equally common, so that there is good reason why it should be specially named as one of the animals that were lawful food. Not only was its flesh permitted to be eaten, but it was evidently considered as a great dainty, inasmuch as the Jachmur is mentioned in 1 Kings iv. 23 as one of the animals which were brought to the royal table. See the passage quoted in full below the illustration.

Even at the present day it is seen near the Red Sea; and as within the memory of man it had a much larger range than can now be assigned to it, we may safely conjecture that it resided in Palestine in sufficient numbers to afford a constant supply of food to the royal residence.

In size the Bubale is about equal to that of a heifer, and its general colour is reddish brown. The head is long and narrow, so that the heavy and deeply-ridged horns seem to stand out with peculiar boldness. The shoulders are rather high, the neck is very ox-like, and from the end of the tail hangs a tuft of long black hair. It is a gregarious animal, and is found in herds, though not of very great numbers.

The Bubale is closely allied to the hartebeest, the well-known antelope of Southern Africa.

THE SHEEP

Importance of Sheep in the Bible—The Sheep the chief wealth of the pastoral tribes—Tenure of land—Value of good pasture-land—Arab shepherds of the present day—Difference between the shepherds of Palestine and England—Wanderings of the flocks in search of food—Value of the wells—How the Sheep are watered—Duties of the shepherd—The shepherd a kind of irregular soldier—His use of the sling—Sheep following their shepherd—Calling the Sheep by name—The shepherd usually a part owner of the flocks—Structure of the sheepfolds—The rock caverns of Palestine—David's adventure with Saul—Penning of the Sheep by night—Use of the dogs—Sheep sometimes brought up by hand—How Sheep are fattened in the Lebanon district—The two breeds of Sheep in Palestine—The broad-tailed Sheep, and its peculiarities—Reference to this peculiarity in the Bible—The Talmudical writers, and their directions to sheep-owners.

We now come to a subject which will necessarily occupy us for some little time.

There is, perhaps, no animal which occupies a larger space in the Scriptures than the Sheep. Whether in religious, civil, or domestic life, we find that the Sheep is bound up with the Jewish nation in a way that would seem almost incomprehensible, did we not recall the light which the New Testament throws upon the Old, and the many allusions to the coming Messiah under the figure of the Lamb that taketh away the sins of the world.

In treating of the Sheep, it will be perhaps advisable to begin the account by taking the animal simply as one of those creatures which have been domesticated from time immemorial, dwelling slightly on those points on which the sheep-owners of the old days differed from those of our own time.

In the first place, the tenure of land was—and is still—entirely different from anything that can be found in our own country. With us, the comparatively large amount of population, placed on a comparatively small area of ground, prohibits the mode of sheep-keeping as practised in the East, where the pasture-lands are of vast extent, and common to all who choose to take their flocks to them. We have at present the Downs and the Highlands as examples of such pasturage, but they are of small extent when compared with the vast plains which are used for this purpose in the East.

The only claim to the land seems, in the old times of the Scriptures, to have lain in cultivation, or perhaps in the land immediately surrounding a well. But any one appears to have taken a piece of ground and cultivated it, or to have dug a well wherever he chose, and thereby to have acquired a sort of right to the soil. The same custom prevails at the present day among the cattle-breeding races of Southern Africa. The banks of rivers, on account of their superior fertility, were considered as the property of the chiefs who lived along their course, but the inland soil was free to all.

Had it not been for this freedom of the land, it would have been impossible for the great men to have nourished the enormous flocks and herds of which their wealth consisted; but, on account of the lack of ownership of the soil, a flock could be moved to one district after another as fast as it exhausted the herbage, the shepherds thus unconsciously imitating the habits of the gregarious animals, which are always on the move from one spot to another.

Pasturage being thus free to all, Sheep had a higher comparative value than is the case with ourselves, who have to pay in some way for their keep. There is a proverb in the Talmud which may be curtly translated, "Land sell, sheep buy."

The value of a good pasture-ground for the flocks is so great, that its possession is well worth a battle, the shepherds being saved from a most weary and harassing life, and being moreover fewer in number than is needed when the pasturage is scanty. Sir S. Baker, in his work on Abyssinia, makes some very interesting remarks upon the Arab herdsmen, who are placed in conditions very similar to those of the Israelitish shepherds in a bad pasture-land.

"The Arabs are creatures of necessity; their nomadic life is compulsory, as the existence of their flocks and herds depends upon the pasturage. Thus, with the change of seasons they must change their localities according to the presence of fodder for their cattle.... The Arab cannot halt in one spot longer than the pasturage will support his flocks. The object of his life being fodder, he must wander in search of the ever-changing supply. His wants must be few, as the constant change of encampment necessitates the transport of all his household goods; thus he reduces to a minimum his domestic furniture and utensils....

"This striking similarity to the descriptions of the Old Testament is exceedingly interesting to a traveller when residing among these curious and original people. With the Bible in one's hand, and these unchanged tribes before the eyes, there is a thrilling illustration of the sacred record; the past becomes the present, the veil of three thousand years is raised, and the living picture is a witness to the exactness of the historical description. At the same time there is a light thrown upon many obscure passages in the Old Testament by the experience of the present customs and figures of speech of the Arabs, which are precisely those that were practised at the periods described....

"Should the present history of the country be written by an Arab scribe, the style of the description would be precisely that of the Old Testament. There is a fascination in the unchangeable features of the Nile regions. There are the vast pyramids that have defied time, the river upon which Moses was cradled in infancy, the same sandy desert through which he led his people, and the watering-places where their flocks were led to drink. The wild and wandering Arabs, who thousands of years ago dug out the wells in the wilderness, are represented by their descendants, unchanged, who now draw water from the deep wells of their forefathers, with the skins that have never altered their fashion.

"The Arabs, gathering with their goats and sheep around the wells to-day, recall the recollection of that distant time when 'Jacob went on his journey, and came into the land of the people of the east. And he looked, and behold a well in the field, and lo! there were three flocks of sheep lying by it,' &c. The picture of that scene would be an illustration of Arab daily life in the Nubian deserts, where the present is a mirror of the past."

Owing to the great number of Sheep which they have to tend, and the peculiar state of the country, the life of the shepherd in Palestine is even now very different from that of an English shepherd, and in the days of the early Scriptures the distinction was even more distinctly marked.

Sheep had to be tended much more carefully than we generally think. In the first place, a thoughtful shepherd had always one idea before his mind,—namely, the possibility of obtaining sufficient water for his flocks. Even pasturage is less important than water, and, however tempting a district might be, no shepherd would venture to take his charge there if he were not sure of obtaining water. In a climate such as ours, this ever-pressing anxiety respecting water can scarcely be appreciated, for in hot climates not only is water scarce, but it is needed far more than in a temperate and moist climate. Thirst does its work with terrible quickness, and there are instances recorded where men have sat down and died of thirst in sight of the river which they had not strength to reach.

In places therefore through which no stream runs, the wells are the great centres of pasturage, around which are to be seen vast flocks extending far in every direction. These wells are kept carefully closed by their owners, and are only opened for the use of those who are entitled to water their flocks at them.

Noontide is the general time for watering the Sheep, and towards that hour all the flocks may be seen converging towards their respective wells, the shepherd at the head of each flock, and the Sheep following him. See how forcible becomes the imagery of David, the shepherd poet, "The Lord is my Shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures (or, in pastures of tender grass): He leadeth me beside the still waters" Ps. xxiii. 1, 2). Here we have two of the principal duties of the good shepherd brought prominently before us,—namely, the guiding of the Sheep to green pastures and leading them to fresh water. Very many references are made in the Scriptures to the pasturage of sheep, both in a technical and a metaphorical sense; but as our space is limited, and these passages are very numerous, only one or two of each will be taken.

In the story of Joseph, we find that when his father and brothers were suffering from the famine, they seem to have cared as much for their Sheep and cattle as for themselves, inasmuch as among a pastoral people the flocks and herds constitute the only wealth. So, when Joseph at last discovered himself, and his family were admitted to the favour of Pharaoh, the first request which they made was for their flocks. "Pharaoh said unto his brethren, What is your occupation? And they said unto Pharaoh, Thy servants are shepherds, both we, and also our fathers.

"They said moreover unto Pharaoh, For to sojourn in the land are we come; for thy servants have no pasture for their flocks; for the famine is sore in the land of Canaan: now therefore, we pray thee, let thy servants dwell in the land of Goshen."

This one incident, so slightly remarked in the sacred history, gives a wonderfully clear notion of the sort of life led by Jacob and his sons. Forming, according to custom, a small tribe of their own, of which the father was the chief, they led a pastoral life, taking their continually increasing herds and flocks from place to place as they could find food for them. For example, at the memorable time when the story of Joseph begins, he was sent by his father to his brothers, who were feeding the flocks, and he wandered about for some time, not knowing where to find them. It may seem strange that he should be unable to discover such very conspicuous objects as large flocks of sheep and goats, but the fact is that they had been driven from one pasture-land to another, and had travelled in search of food all the way from Shechem to Dothan.

In 1 Chron. iv. 39, 40, we read of the still pastoral Israelites that "they went to the entrance of Gedor, even unto the east side of the valley, to seek pasture for their flocks. And they found fat pasture and good, and the land was wide, and quiet, and peaceable."

How it came to be quiet and peaceable is told in the context. It was peaceable simply because the Israelites were attracted by the good pasturage, attacked the original inhabitants, and exterminated them so effectually that none were left to offer resistance to the usurpers. And we find from this passage that the value of good pasture-land where the Sheep could feed continually without being forced to wander from one spot to another was so considerable, that the owners of the flocks engaged in war, and exposed their own lives, in order to obtain so valuable a possession.

As to the figurative passages, they are far too numerous to be quoted, and are found throughout the whole of the Old and New Testaments. For example, see Psalm lxxix. 13, "So we Thy people and the sheep of Thy pasture will give Thee thanks for ever." And again, "I will feed them upon the mountains of Israel by the rivers, and in all the inhabited places of the country. I will feed them in a good pasture, and upon the high mountains of Israel shall their fold be: there shall they lie in a good fold, and in a fat pasture shall they feed upon the mountains of Israel" (Ezek. xxxiv. 13, 14).

We will now look at one or two of the passages that mention watering the Sheep—a duty so imperative on an Oriental shepherd, and so needless to our own.

In the first place we find that most graphic narrative which occurs in Gen xxix. to which a passing reference has already been made. When Jacob was on his way from his parents to the home of Laban in Padan-aram, he came upon the very well which belonged to his uncle, and there saw three flocks of Sheep lying around the well, waiting until the proper hour arrived. According to custom, a large stone was laid over the well, so as to perform the double office of keeping out the sand and dust, and of guarding the precious water against those who had no right to it. And when he saw his cousin Rachel arrive with the flock of which she had the management, he, according to the courtesy of the country and the time, rolled away the ponderous barrier, and poured out water into the troughs for the Sheep which Rachel tended.

About two hundred years afterwards, we find Moses performing a similar act. When he was obliged to escape into Midian on account of his fatal quarrel with a tyrannical Egyptian, he sat down by a well, waiting for the time when the stone might be rolled away, and the water be distributed. Now it happened that this well belonged to Jethro, the chief priest of the country, whose wealth consisted principally of Sheep. He entrusted his flock to the care of his seven daughters, who led their Sheep to the well and drew water as usual into the troughs. Presuming on their weakness, other shepherds came and tried to drive them away, but were opposed by Moses, who drove them away, and with his own hands watered the flock.

Now in both these examples we find that the men who performed the courteous office of drawing the water and pouring it into the sheep-troughs married afterwards the girl to whose charge the flocks had been committed. This brings us to the Oriental custom which has been preserved to the present day.

The wells at which the cattle are watered at noon-day are the meeting-places of the tribe, and it is chiefly at the well that the young men and women meet each other. As each successive flock arrives at the well, the number of the people increases, and while the sheep and goats lie patiently round the water, waiting for the time when the last flock shall arrive, and the stone be rolled off the mouth of the well, the gossip of the tribe is discussed, and the young people have ample opportunity for the pleasing business of courtship.

As to the passages in which the wells, rivers, brooks, water-springs, are spoken of in a metaphorical sense, they are too numerous to be quoted.

And here I may observe, that in reality the whole of Scripture has its symbolical as well as its outward signification; and that, until we have learned to read the Bible strictly according to the spirit, we cannot understand one-thousandth part of the mysteries which it conceals behind its veil of language; nor can we appreciate one-thousandth part of the treasures of wisdom which lie hidden in its pages from those who have eyes and cannot see, ears and cannot hear.