полная версия

полная версияBible Animals

The enormous size of the horns of an ox which was in all probability the Urus is mentioned by another writer, who also alludes to their use as drinking vessels. He states that some of these horns were so large as to hold about four gallons, and then proceeds to remark that their primitive use as drinking-cups was the reason why Bacchus was represented as wearing horns, and was sometimes worshipped under the form of a bull.

It is worthy of notice, that the Sanscrit root Ur is retained in the name of the enormous Indian ox, the Gaur, a term which is formed from two words, namely, Gau, or Ghoo, a cow, and Ur, so that the name signifies Wild Cow.

As to the size of the animal Urus, it is evident, by measurement of certain remains, that it must have well deserved Cæsar's comparison with the elephant. A skull that is described by Cuvier gave the following measurements. Width of skull between the bases of the horn-cores (i.e. the bony projections on which the hollow horns are set), rather more than twelve inches and an half. Circumference of the cores at the base, twelve inches and nine-tenths. Length of the cores, twenty-seven inches and nine-tenths; and distances between their tips, thirty-two inches and a half.

According to the proportions of the domesticated ox, these measurements indicated that the animal was twelve feet in length, and six feet and a half in height. Now, if the reader will sketch out on a wall an ox of these dimensions, he will appreciate the enormous dimensions of the ancient Urus, far better than can be done by merely reading figures in a book.

But this animal, gigantic as it was, is not the largest specimen that has been discovered. A portion of an Urus skull was discovered in the Avon, at Melksham, near Bath, the horn-cores of which, as described by Mr. H. Woods, were seventeen inches and a half in circumference, thirty-six inches and a half in length, and the distance from tip to tip was thirty-nine inches. Taking the same proportions as those of the ordinary ox, the author shows that the skull in question belonged to an animal very much larger than that which was described by Cuvier. In another specimen the distance between the tips of the horn-cores was forty-two inches, but their length only thirty-six.

Of course, the size of the horn-cores gives little indication of the dimensions of the horns themselves, and the principal point to be noticed is the shape of the core, which in some specimens, though not in all, instead of presenting the regular double curvature with which we are so familiar in our domestic oxen, first curves outwards, then bends backwards or a little downwards and forwards. This peculiarity in the shape of the horns is specially noted by Cæsar, and we may therefore receive with more security his account of their enormous size.

A curious rabbinical legend of the Reêm is given in Lewysohn's "Zoologie des Talmuds." When the ark was complete, and all the beasts were commanded to enter, the Reêm was unable to do so, because it was too large to pass through the door. Noah and his sons therefore were obliged to tie the animal by a rope to the ark, and to tow it behind; and, in order to prevent it from being strangled, they tied the rope, not round its neck, but to its horn.

The same writer very justly remarks that the Scriptural and Talmudical accounts of the Reêm have one decided distinction. The Scripture speaks chiefly of its fierceness, its untameable nature, its strength, and its swiftness, as its principal characteristics, while the Talmud speaks almost exclusively of its size. It was evidently the largest animal of which the writers had ever heard, and, according to Oriental wont, they exaggerated it preposterously. Whenever the Talmudical writers treat of animals with which they are personally acquainted, they are simple, straightforward, and accurate. But, as soon as they come to animals unknown to them except by hearsay, they go off into the wildest extravagances, such, for example, as asserting that the leopard is a hybrid between the wild boar and the lioness. The exaggerated statements concerning the Reêm show therefore that the animal must have been extinct long before the time of the writers.

The question now arises, What is the distinction between the ancient Urus and our modern cattle? The answer is simple enough. The difference in the shape of the horn-cores is, as has been shown, not characteristic of the animal in general, but only of certain individuals; while other variations in the shape and length of certain bones are of too little consequence to be accepted as bases whereon to found a new genus or even species, and we may therefore assume that the Urus of Cæsar, the Reêm of Scripture, was nothing more than a very large variety of the ox, modified of course in aspect and habits by the locality in which it lived. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that Mr. Dawkins, in the treatise to which reference has already been made, has "traced the gigantic Urus from the earliest Pleistocene times through the pre-historic period at least as far as the twelfth century after Christ."

The reader may remember that in Cæsar's brief but graphic account of the Urus, he mentions that it was hunted by those who wished to distinguish themselves. Now, on many of the sculptures of Nineveh, there are delineations of bull hunts, which show, as Mr. Layard justly observes, that the wild bull appears to have been considered scarcely less formidable and noble game than the lion. The king himself is shown as attacking it, while the warriors partake of the sport either mounted or on foot.

The exact variety of the wild bull which is being chased is not very recognisable. It certainly is not the ordinary domestic animal, the shape approaching somewhat to that of the antelope. The body is covered with marks which are evidently intended to represent hair, though it does not follow that the hair need be thick and shaggy like that of the bison tribe.

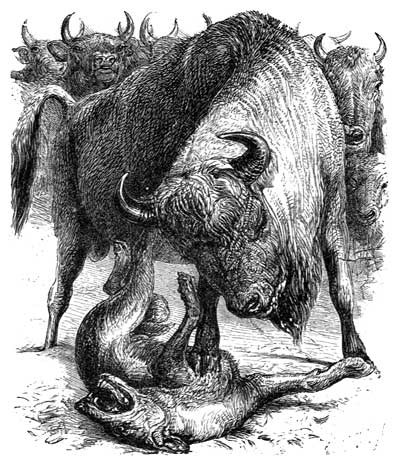

THE BISON

The Bison tribe and its distinguishing marks—Its former existence in Palestine—Its general habits—Origin of its name—Its musky odour—Size and speed of the Bison—Its dangerous character when brought to bay—Its defence against the wolf—Its untameable disposition.

A few words are now needful respecting the second animal which has been mentioned in connexion with the Reêm; namely, the Bison, or Bonassus. The Bisons are distinguishable from ordinary cattle by the thick and heavy mane which covers the neck and shoulders, and which is more conspicuous in the male than in the female. The general coating of the body is also rather different, being thick and woolly instead of lying closely to the skin like that of the other oxen. The Bison certainly inhabited Palestine, as its bones have been found in that country. It has, however, been extinct in the Holy Land for many years, and, not being an animal that is capable of withstanding the encroachments of man, it has gradually died out from the greater part of Europe and Asia, and is now to be found only in a very limited locality, chiefly in a Lithuanian forest, where it is strictly preserved, and in some parts of the Caucasus. There it still preserves the habits which made its ancient and gigantic relative so dangerous an animal. Unlike the buffalo, which loves the low-lying and marshy lands, the Bison prefers the high wooded localities, where it lives in small troops.

Its name of Bison is a modification of the word Bisam, or musk, which was given to it on account of the strong musky odour of its flesh, which is especially powerful about the head and neck. This odour is not so unpleasant as might be supposed, and those who have had personal experience of the animal say that it bears some resemblance to the perfume of violets. It is developed most strongly in the adult bulls, the cows and young male calves only possessing it in a slight degree.

BISON KILLING WOLF.

"Will the unicorn he willing to serve thee?"—Job xxxix. 9.

It is a tolerably large animal, being about six feet high at the shoulder—a stature nearly equivalent to that of the ordinary Asiatic elephant; and, in spite of its great bulk, is a fleet and active animal, as indeed is generally the case with those oxen which inhabit elevated localities. Still, though it can run with considerable speed, it is not able to keep up the pace for any great distance, and at the end of a mile or two can be brought to bay.

Like most animals, however large and powerful they may be, it fears the presence of man, and, if it sees or scents a human being, will try to slip quietly away; but when it is baffled in this attempt, and forced to fight, it becomes a fierce and dangerous antagonist, charging with wonderful quickness, and using its short and powerful horns with great effect. A wounded Bison, when fairly brought to bay, is perhaps as awkward an opponent as can be found, and to kill it without the aid of firearms is no easy matter.

Although the countries in which it lives are infested with wolves, it seems to have no fear of them when in health; and, even when pressed by their winter's hunger, the wolves do not venture to attack even a single Bison, much less a herd of them. Like other wild cattle, it likes to dabble in muddy pools, and is fond of harbouring in thickets near such localities; and those who have to travel through the forest keep clear of such spots, unless they desire to drive out the animal for the purpose of killing it.

Like the extinct Aurochs, the Bison has never been domesticated, and, although the calves have been captured while very young, and attempts have been made to train them to harness, their innate wildness of disposition has always baffled such efforts.

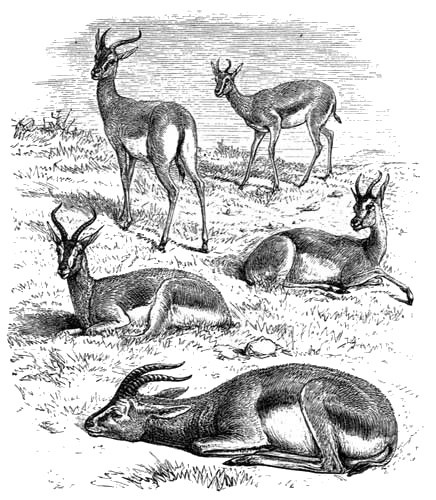

THE GAZELLE, OR ROE OF SCRIPTURE

The Gazelle identified with the Tsebi, i.e. the Roe or Roebuck of Scripture—Various passages relating to the Tsebi—Its swiftness, its capabilities as a beast of chase, its beauty, and the quality of its flesh—The Tsebiyah rendered in Greek as Tabitha, and translated as Dorcas, or Gazelle—Different varieties of the Gazelle—How the Gazelle defends itself against wild beasts—Chase of the Gazelle—The net, the battue, and the pitfall—Coursing the Gazelle with greyhounds and falcons—Mr. Chasseaud's account of a hunting party—Gentleness of the Gazelle.

We now leave the Ox tribe, and come to the Antelopes, several species of which are mentioned in the Scriptures. Four kinds of antelope are found in or near the Holy Land, and there is little doubt that all of them are mentioned in the sacred volume.

The first that will be described is the well-known Gazelle, which is acknowledged to be the animal that is represented by the word Tsebi, or Tsebiyah. The Jewish Bible accepts the same rendering. This word occurs many times, sometimes as a metaphor, and sometimes representing some animal which was lawful food, and which therefore belonged to the true ruminants. Moreover, its flesh was not only legally capable of being eaten, but was held in such estimation that it was provided for the table of Solomon himself, together with other animals which will be described in their turn.

We will first take the passages where the word is used metaphorically, or as a poetical image. That it was exceedingly swift of foot is evident from several instances in which the animal is mentioned. For example, in 2 Sam. ii. 18, we are told that Asahel, the brother of Joab, was "as light of foot as a wild roe," or, as the passage may also be translated, "one of the roes that is in the field." And in 1 Chron. xii. 8, we find the following description of eleven warriors who attached themselves to David:—"Of the Gadites there separated themselves unto David into the hold to the wilderness men of might, and men of war fit for the battle, that could handle shield and buckler, whose faces were like the faces of lions, and were as swift as the roes upon the mountains."

That it was a beast of chase is as plainly to be gathered from the sacred writings. See, for example, Prov. vi. 4, 5: "Give not sleep to thine eyes, nor slumber to thine eyelids. Deliver thyself as a roe from the hand of the hunter, and as a bird from the hand of the fowler."

The same imagery is employed by the prophet Isaiah, xiii. 13, 14:—

"Therefore I will shake the heavens, and the earth shall remove out of her place, in the wrath of the Lord of hosts, and in the day of His fierce anger. And it shall be as the chased roe, and as a sheep that no man taketh up: they shall every man turn to his own people, and flee every one into his own land."

Having now learned that the Tsebi was very fleet of foot and a beast of chase, we come to another series of passages, which show that it was an animal of acknowledged beauty. In that most remarkable poem, the Song of Solomon, or the "Song of Songs," as it is more rightly named, there are repeated allusions to the Tsebi. In some cases the name of the Roe is used as a sort of adjuration—"I charge thee by the roes;" and in others the lover, whether man or woman, is compared to the Roe. There is one consecutive series of passages in which the word is repeatedly used. See Cant. ii. 7-9: "I charge you, O ye daughters of Jerusalem, by the roes, and by the hinds of the field, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, till he please. The voice of my beloved! behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills. My beloved is like a roe or a young hart." And in the last verse of the poem the same image is repeated—"Make haste, my beloved, and be thou like to a roe or to a young hart upon the mountains of spices."

Allusion is made to the beauty of the Roe, or Gazelle, in a well-known name, Tabitha, which is, in fact, a slight corruption of the Hebrew Tsebiyah, and is translated into Greek as Dorcas, or Gazelle. "Now there was at Joppa a certain disciple named Tabitha, which by interpretation is called Dorcas (i.e. the Gazelle). This woman was full of good works and alms deeds which she did."

As to the flesh of the Gazelle, or Roe, it is mentioned in Deut. xii. 15, xiv. 5, as one of the animals that affords lawful food; and the same permission is reiterated in xv. 22, with the proviso that the blood shall be poured out on the earth like water.

Having now glanced at the various passages of Scripture wherein the Gazelle is mentioned, we will proceed to the animal itself, its appearance, locality, and general habits, in order to see how they agree with the Scriptural allusions to the Tsebi.

As to its flesh, it is even now considered a great dainty, although it is not at all agreeable to European taste, being hard, dry, and without flavour. Still, as has been well remarked, tastes differ as well as localities, and an article of food which is a costly luxury in one land is utterly disdained in another, and will hardly be eaten except by one who is absolutely dying of starvation.

The Gazelle is very common in Palestine in the present day, and, in the ancient times, must have been even more plentiful. There are several varieties of it, which were once thought to be distinct species, but are now acknowledged to be mere varieties, all of which are referable to the single species Gazella Dorcas. There is, for example, the Corinna, or Corine Antelope, which is a rather boldly-spotted female; the Kevella Antelope, in which the horns are slightly flattened; the small variety called the Ariel, or Cora; the grey Kevel, which is a rather large variety; and the Long-horned Gazelle, which owes its name to a rather large development of the horns.

THE GAZELLE, (Gazella Dorcus) OR ROE OF SCRIPTURE.

"Behold, he cometh leaping upon the mountains, skipping upon the hills. My beloved is like a roe or a young hart."—Cant. ii. 8, 9.

Whatever variety may inhabit any given spot, they all have the same habits. They are gregarious animals, associating together in herds often of considerable size, and deriving from their numbers an element of strength which would otherwise be wanting. Against mankind, numbers are of no avail; but when the agile though feeble Gazelle has to defend itself against the predatory animals of its own land, it can only defend itself by the concerted action of the whole herd. Should, for example, the wolves prowl round a herd of Gazelles, after their treacherous wont, the Gazelles instantly assume a posture of self-defence. They form themselves into a compact phalanx, all the males coming to the front, and the strongest and boldest taking on themselves the honourable duty of facing the foe. The does and the young are kept within their ranks, and so formidable is the array of sharp, menacing horns, that beasts as voracious as the wolf, and far more powerful, have been known to retire without attempting to charge.

As a rule, however, the Gazelle does not desire to resist, and prefers its legs to its horns as a mode of insuring safety. So fleet is the animal, that it seems to fly over the ground as if propelled by volition alone, and its light, agile frame is so enduring, that a fair chase has hardly any prospect of success. Hunters, therefore, prefer a trap of some kind, if they chase the animal merely for food or for the sake of its skin, and contrive to kill considerable numbers at once. Sometimes they dig pitfalls, and drive the Gazelles into them by beating a large tract of country, and gradually narrowing the circle. Sometimes they use nets, such as have already been described, and sometimes they line the sides of a ravine with archers and spearmen, and drive the herd of Gazelles through the treacherous defile.

These modes of slaughter are, however, condemned by the true hunter, who looks upon those who use them much in the same light as an English sportsman looks on a man who shoots foxes. The greyhound and the falcon are both employed in the legitimate capture of the Gazelle, and in some cases both are trained to work together. Hunting the Gazelle with the greyhound very much resembles coursing in our own country, and chasing it with the hawk is exactly like the system of falconry that was once so popular an English sport, and which even now shows signs of revival.

It is, however, when the dog and the bird are trained to work together that the spectacle becomes really novel and interesting to an English spectator.

As soon as the Gazelles are fairly in view, the hunter unhoods his hawk, and holds it up so that it may see the animals. The bird fixes its eye on one Gazelle, and by that glance the animal's doom is settled. The falcon darts after the Gazelles, followed by the dog, who keeps his eye on the hawk, and holds himself in readiness to attack the animal that his feathered ally may select. Suddenly the falcon, which has been for some few seconds hovering over the herd of Gazelles, makes a stoop upon the selected victim, fastening its talons in its forehead, and, as it tries to shake off its strange foe, flaps its wings into the Gazelle's eyes so as to blind it. Consequently, the rapid course of the antelope is arrested, so that the dog is able to come up and secure the animal while it is struggling to escape from its feathered enemy. Sometimes, though rarely, a young and inexperienced hawk swoops down with such reckless force that it misses the forehead of the Gazelle, and impales itself upon the sharp horns, just as in England the falcon is apt to be spitted on the bill of the heron.

The most sportsmanlike mode of hunting the Gazelle is to use the falcon alone; but for this sport a bird must possess exceptional strength, swiftness, and intelligence. A very spirited account of such a chase is given by Mr. G. W. Chasseaud, in his "Druses of the Lebanon:"—

"Whilst reposing here, our old friend with the falcon informs us that at a short distance from this spot is a khan called Nebbi Youni, from a supposition that the prophet Jonah was here landed by the whale; but the old man is very indignant when we identify the place with a fable, and declare to him that similar sights are to be seen at Gaza and Scanderoon. But his good humour is speedily recovered by reverting to the subject of the exploits and cleverness of his falcon. This reminds him that we have not much time to waste in idle talk, as the greater heats will drive the gazelles from the plains to the mountain retreats, and lose us the opportunity of enjoying the most sportsmanlike amusement in Syria. Accordingly, bestriding our animals again, we ford the river at that point where a bridge once stood.

"We have barely proceeded twenty minutes before the keen eye of the falconer has descried a herd of gazelles quietly grazing in the distance. Immediately he reins in his horse, and enjoining silence, instead of riding at them, as we might have felt inclined to do, he skirts along the banks of the river, so as to cut off, if possible, the retreat of these fleet animals where the banks are narrowest, though very deep, but which would be cleared at a single leap by the gazelles. Having successfully accomplished this manœuvre, he again removes the hood from the hawk, and indicates to us that precaution is no longer necessary. Accordingly, first adding a few slugs to the charges in our barrels, we balance our guns in an easy posture, and, giving the horses their reins, set off at full gallop, and with a loud hurrah, right towards the already startled gazelles.

"The timid animals, at first paralysed by our appearance, stand and gaze for a second terror-stricken at our approach; but their pause is only momentary; they perceive in an instant that the retreat to their favourite haunts has been secured, and so they dash wildly forward with all the fleetness of despair, coursing over the plain with no fixed refuge in view, and nothing but their fleetness to aid in their delivery. A stern chase is a long chase, and so, doubtless, on the present occasion it would prove with ourselves, for there is many and many a mile of level country before us, and our horses, though swift of foot, stand no chance in this respect with the gazelles.

"Now, however, the old man has watched for a good opportunity to display the prowess and skill of his falcon: he has followed us only at a hand-gallop; but the hawk, long inured to such pastime, stretches forth its neck eagerly in the direction of the flying prey, and being loosened from its pinions, sweeps up into the air like a shot, and passes overhead with incredible velocity. Five minutes more, and the bird has outstripped even the speed of the light-footed gazelle; we see him through the dust and haze that our own speed throws around us, hovering but an instant over the terrified herd; he has singled out his prey, and, diving with unerring aim, fixes his iron talons into the head of the terrified animal.

"This is the signal for the others to break up their orderly retreat, and to speed over the plain in every direction. Some, despite the danger that hovers on their track, make straight for their old and familiar haunts, and passing within twenty yards of where we ride, afford us an opportunity of displaying our skill as amateur huntsmen on horseback; nor does it require but little nerve and dexterity to fix our aim whilst our horses are tearing over the ground. However, the moment presents itself, the loud report of barrel after barrel startles the unaccustomed inmates of that unfrequented waste; one gazelle leaps twice its own height into the air, and then rolls over, shot through the heart; another bounds on yet a dozen paces, but, wounded mortally, staggering, halts, and then falls to the ground.

"This is no time for us to pull in and see what is the amount of damage done, for the falcon, heedless of all surrounding incidents, clings firmly to the head of its terrified victim, flapping its strong wings awhile before the poor brute's terrified eyes, half blinding it and rendering its head dizzy; till, after tearing round and round with incredible speed, the poor creature stops, panting for breath, and, overcome with excessive terror, drops down fainting upon the earth. Now the air resounds with the acclamations and hootings of the ruthless victors.

"The old man is wild in his transports of delight. More certain of the prowess of his bird than ourselves, he has stopped awhile to gather together the fruits of our booty, and, with these suspended to his saddle bow, he canters up leisurely, shouting lustily the while the praises of his infallible hawk; then getting down, and hoodwinking the bird again, he first of all takes the precaution of fastening together the legs of the fallen gazelle, and then he humanely blows up into its nostrils. Gradually the natural brilliancy returns to the dimmed eyes of the gazelle, then it struggles valiantly, but vainly, to disentangle itself from its fetters.