полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

Our concern here is with the ancient Britons. It is unnecessary for us to glean evidence from Australia, South America, or Central Africa to ascertain the character of their early religious conceptions and practices. There is sufficient local evidence to show that a definite body of beliefs lay behind their worship of trees, rivers, lakes, wells, standing stones, and of the sun, moon, and stars. Our ancestors do not appear to have worshipped natural objects either because they were beautiful or impressive, but chiefly because they were supposed to contain influences which affected mankind either directly or indirectly. These influences were supposed to be under divine control, and to emanate, in the first place, from one deity or another, or from groups of deities. A god or goddess was worshipped whether his or her influence was good or bad. The deity who sent disease, for instance, was believed to be the controller of disease, and to him or her offerings were made so that a plague might cease. Thus in the Iliad offerings are made to the god Mouse-Apollo, who had caused an epidemic of disease.

Trees and wells were connected with the sky and the heavenly bodies. The deity who caused thunder and lightning had his habitation at times in the oak, the fir, the rowan, the hazel, or some other tree. He was the controller of the elements. There are references in Gaelic charms to "the King of the Elements".

The belief in an intimate connection between a well, a tree, and the sky appears to have been a product of a quaint but not unintelligent process of reasoning.164 The early folk were thinkers, but their reasoning was confined within the limits of their knowledge, and biassed by preconceived ideas. To them water was the source of all life. It fell from the sky as rain, or bubbled up from the underworld to form a well from which a stream flowed. The well was the mother of the stream, and the stream was the mother of the lake. It was believed that the well-water was specially impregnated with the influences that sustained life. The tree that grew beside the well was nourished by it. If this tree was a rowan, its red berries were supposed to contain in concentrated form the animating influence of the deity; the berries cured diseases, and thus renewed youth, or protected those who used them as charms against evil influences. They were luck-berries. If the tree was a hazel, its nuts were similarly efficacious; if an oak, its acorns were regarded likewise as luck-bringers. The parasitic plant that grew on the tree was supposed to be stronger and more influential than the tree itself. This belief, which is so contrary to our way of thinking, is accounted for in an old Gaelic story in which a supernatural being says:

"O man that for Fergus of the feasts dost kindle fire … never burn the King of the Woods. Monarch of Innisfail's forest the woodbine is, whom none may hold captive; no feeble sovereign's effort it is to hug all tough trees in his embrace."

The weakly parasite was thus regarded as being very powerful. That may be the reason why the mistletoe was reverenced, and why its milk-white berries were supposed to have curative and life-prolonging qualities.

Although the sacred parasite was not used for firewood, it served as a fire-producer. Two fire-sticks, one from the soft parasite and one from the hard wood of the tree to which it clung, were rubbed together until sparks issued forth and fell on dry leaves or dry grass. The sparks were blown until a flame sprang up. At this flame of holy fire the people kindled their brands, which they carried to their houses. The house fires were extinguished once a year and relit from the sacred flames. Fire was itself a deity, and the deity was "fed" with fuel. "Need fires" (new fires)165 were kindled at festivals so that cattle and human beings might be charmed against injury. These festivals were held four times a year, and the "new-fire" custom lingers in those districts where New Year's Day, Midsummer, May Day, and Hallowe'en bon-fires are still being regularly kindled.

The fact that fire came from a tree induced the early people to believe that it was connected with lightning, and therefore with the sky god who thundered in the heavens. This god was supposed to wield a thunder-axe or thunder-hammer with which he smote the sky (believed to be solid) or the hills. With his axe or hammer he shaped the "world house".

In Scotland, a goddess, who is remembered as "the old wife",166 was supposed to wield the hammer, or to ride across the sky on a cloud and throw down "fire-balls" that set the woods in flame. Here we find, probably as a result of culture mixing, a fusion of beliefs connected with the thunder god and the mother goddess.

Rain fell when the sky deity sent thunder and lightning. To early man, who took fire from a tree which was nourished by a well, fire and water seemed to be intimately connected.167 The red berries on the sacred tree were supposed to contain fire, or the essence of fire. When he made rowan-berry wine, he regarded it as "fire water" or "the water of life". He drank it, and thus introduced into his blood fire which stimulated him. In his blood was "the vital spark". When he died the blood grew cold, because the "vital spark" had departed from it.

In the water fire lived in another form. Fish were found to be phosphorescent. The fish in the pool was at any rate regarded as a form of the deity who nourished life and was the origin of life. A specially sacred fish was the salmon. It was observed that this fish had red spots, and these were accounted for by the myth that the red berries or nuts from the holy tree dropped into the well and were swallowed by the salmon. The "chief" or "king" of the salmon was called "the salmon of wisdom". If one caught the "salmon of wisdom" and, when roasting it, tasted the first portion of juice that came from its body, one obtained a special instalment of concentrated wisdom, and became a seer, or magician, or Druid.

The salmon was reverenced also because it was a migratory fish. Its comings and goings were regular as the seasons, and seemed to be controlled by the ruler of the elements with whom it was intimately connected. One of its old Gaelic names was orc (pig). It was evidently connected with that animal; the sea-pig was possibly a form of the deity. The porpoise was also an orc.168

Hidden in the well lay a great monster which in Gaelic and Welsh stories is referred to as "the beast", "the serpent", or "the great worm". Ultimately it was identified with the dragon with fiery breath. An Irish story connects the salmon and dragon. It tells that a harper named Cliach, who had the powers of a Druid, kept playing his harp until a lake sprang up. This lake was visited by a goddess and her attendants, who had assumed the forms of beautiful birds. It was called Loch Bél Seád ("lake of the jewel mouth") because pearls were found in it, and Loch Crotto Cliach ("lake of Cliach's harps"). Another name was Loch Bél Dragain ("dragon-mouth lake"), because Ternog's nurse caught "a fiery dragon in the shape of a salmon" and she was induced to throw this salmon into the loch. The early Christian addition to the legend runs: "And it is that dragon that will come in the festival of St. John, near the end of the world, in the reign of Flann Cinaidh. And it is of it and out of it shall grow the fiery bolt which will kill three-fourth of the people of the world."169 Here fire is connected with the salmon.

The salmon which could transform itself into a great monster guarded the tree and its life-giving berries and the treasure offered to the deity of the well. Apparently its own strength was supposed to be derived from or concentrated in the berries. The queen of the district obtained the supernatural power she was supposed to possess from the berries too, and stories are told of a hero who was persuaded to enter the pool and pluck the berries for the queen. He was invariably attacked by the "beast", and, after handing the berries to the queen, he fell down and died. There are several versions of this story. In one version a specially valued gold ring, a symbol of authority, is thrown into the pool and swallowed by the salmon. The hero catches and throws the salmon on to the bank. When he plucks the berries, he is attacked by the monster and kills it. Having recovered the ring, he gives it to the princess, who becomes his wife. Apparently she will be chosen as the next queen, because she has eaten the salmon and obtained the gold symbol.

It may be that this story had its origin in the practice of offering a human sacrifice to the deity of the pool, so that the youth-renewing red berries might be obtained for the queen, the human representative of the deity. Her fate was connected with the ring of gold in which, as in the berries, the influence of the deity was concentrated.

Polycrates of Samos, a Hellenic sea-king, was similarly supposed to have his "luck" connected with a beautiful seal-stone, the most precious of his jewels. On the advice of Pharaoh Amasis of Egypt he flung it into the sea. According to Herodotus, it was to avert his doom that he disposed of the ring. But he could not escape his fate. The jewel came back; it was found a few days later in the stomach of a big fish.

In India, China, and Japan dragons or sea monsters are supposed to have luck pearls which confer great power on those who obtain possession of them. The famous "jewel that grants all desires" and the jewels that control the ebb and flow of tides are obtained from, and are ultimately returned to, sea-monsters of the dragon order.

The British and Irish myths about sacred gold or jewels obtained from the dragon or one of its forms were taken over with much else by the early Christian missionaries, and given a Christian significance. Among the legends attached to the memory of the Irish Saint Moling is one that tells how he obtained treasure for Christian purposes. His fishermen caught a salmon and found in its stomach an ingot of gold. Moling divided the gold into three parts—"one third for the poor, another for the ornamenting of shrines, a third to provide for labour and work".

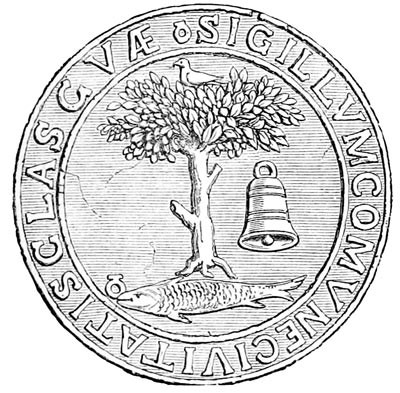

The most complete form of the ancient myth is, however, found in the life of Glasgow's patron saint, St. Kentigern (St. Mungo). A queen's gold ring had been thrown into the River Clyde, and, as she was unable, when asked by the king, to produce it, she was condemned to death and cast into a dungeon. The queen appealed to St. Kentigern, who instructed her messenger to catch a fish in the river and bring it to him. A large fish "commonly called a salmon" was caught. In its stomach was found the missing ring. The grateful queen, on her release, confessed her sins to the saint and became a Christian. St. Mungo's seal, now the coat of arms of Glasgow, shows the salmon with a ring in its mouth, below an oak tree, in the branches of which sits, as the oracle bird, a robin red-breast. A Christian bell dangles from a branch of the tree.

Seal of City of Glasgow, 1647-1793, showing Tree, Bird, Salmon, and Bell

That the Glasgow saint took the place of a Druid,170 so that the people might say "Kentigern is my Druid" as St. Columba said "Christ is my Druid", is suggested by his intimate connection, as shown in his seal, with the sacred tree of the "King of the Elements", the oracular bird (the thunder bird), the salmon form of the deity, and the power-conferring ring. As the Druids produced sacred fire from wood, so did St. Kentigern. It is told that when a youth his rivals extinguished the sacred fire under his care. Kentigern went outside the monastery and obtained "a bough of growing hazel and prayed to the 'Father of Lights'". Then he made the sign of the cross, blessed the bough, and breathed on it.

"A wonderful and remarkable thing followed. Straightway fire coming forth from heaven, seizing the bough, as if the boy had exhaled flames for breath, sent forth fire, vomiting rays, and banished all the surrounding darkness.... God therefore sent forth His light, and led him and brought him into the monastery.... That hazel from which the little branch was taken received a blessing from St. Kentigern, and afterwards began to grow into a wood. If from that grove of hazel, as the country folks say, even the greenest branch is taken, even at the present day, it catches fire like the driest material at the touch of fire...."

A red-breast, which was kept as a pet at the monastery, was hunted by boys, who tore off its head. Kentigern restored the bird to life. The robin was hunted down in some districts as was the wren in other districts. An old rhyme runs:

A robin and a wrenAre God's cock and hen.In Pagan times the oracular bird connected with the holy tree was sacrificed annually. The robin represented the god and the wren (Kitty or Jenny Wren) the goddess in some areas. In Gaelic, Spanish, Italian, and Greek the wren is "the little King" or "the King of Birds". A Gaelic folk-tale tells that the wren flew highest in a competition held by the birds for the kingship, by concealing itself on an eagle's back. When the eagle reached its highest possible altitude, the wren rose above it and claimed the honour of kingship. In the Isle of Man the wren used to be hunted on St. Stephen's Day. Elsewhere it was hunted on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. The dead bird was carried on a pole at the head of a procession and buried with ceremony in a churchyard.

In Scotland the shrew mouse was hunted in like manner, and buried under an apple tree. A standing stone in Perthshire is called in Gaelic "stone of my little mouse". As there were mouse feasts in ancient Scotland, it would appear that a mouse god like Smintheus (Mouse-Apollo) was worshipped in ancient times. Mouse cures were at one time prevalent. The liver of the mouse171 was given to children who were believed to be on the point of death. They rallied quickly after swallowing it. Roasted mouse was in England and Scotland a cure for whooping-cough and smallpox. The Boers in South Africa are perpetuating this ancient folk-cure.172 In Gaelic folk-lore the mouse deity is remembered as lucha sith ("the supernatural mouse").

There still survive traces of the worship of a goddess who is remembered as Bride in England and Scotland, and as Brigit in Ireland. A good deal of the lore connected with her has been attached to the memory of St. Brigit of Ireland.

February 1st (old style) was known as Bride's Day. Her birds were the wood linnet, which in Gaelic is called "Bird of Bride", and the oyster catcher called "Page of Bride", while her plant was the dandelion (am bearnan brìde), the "milk" of which was the salvation of the early lamb. On Bride's Day the serpent awoke from its winter sleep and crept from its hole. This serpent is called in Gaelic "daughter of Ivor", an ribhinn ("the damsel"), &c.

The white serpent was, like the salmon, a source of wisdom and magical power. It was evidently a form of the goddess. Brigit was the goddess of the Brigantes, a tribe whose territory extended from the Firth of Forth to the midlands of England.173 The Brigantes took possession of a part of Ireland where Brigit had three forms as the goddess of healing, the goddess of smith-work, and the goddess of poetry, and therefore of metrical magical charms. Some think her name signifies "fiery arrow". She was the source of fire, and was connected with different trees in different areas. The Bride-wells were taken over by Saint Bride.

The white serpent, referred to in the legends associated with Farquhar, the physician, and Michael Scott, sometimes travelled very swiftly by forming itself into a ring with its tail in its mouth. This looks like the old Celtic solar serpent. If the serpent were cut in two, the parts wriggled towards a stream and united as soon as they touched water. If the head were not smashed, it would become a beithis, the biggest and most poisonous variety of serpent.174 The "Deathless snake" of Egypt, referred to in an ancient folk-tale, was similarly able to unite its severed body. Bride's serpent links with the serpent dragons of the Far East, which sleep all winter and emerge in spring, when they cause thunder and send rain, spit pearls, &c. Dr. Alexander Carmichael translates the following Gaelic serpent-charm:

To-day is the day of Bride,The serpent shall come from his hole;I will not molest the serpentAnd the serpent will not molest me.De Visser175 quotes the following from a Chinese text referring to the dragons:

If we offer a deprecatory service to them,They will leave their abodes;If we do not seek the dragonsThey will also not seek us.The serpent, known in Scotland as nathair challtuinn ("snake of the hazel grove"), had evidently a mythological significance. Leviathan is represented by the Gaelic cirein cròin (sea-serpent), also called mial mhòr a chuain ("the great beast of the sea") and cuairtag mhòr a chuain ("the great whirlpool of the sea"); a sea-snake was supposed to be located in Corryvreckan whirlpool. Kelpies and water horses and water bulls are forms assumed by the Scottish dragon. There are Far Eastern horse-and bull-dragons.

In ancient British lore there are references to souls in serpent form. A serpent might be a "double" like the Egyptian "Ka". It was believed in Wales that snake-souls were concealed in every farm-house. When one crept out from its hiding-place and died, the farmer or his wife died soon afterwards. Lizards were supposed to be forms assumed by women after death.176 The otter, called in Scottish Gaelic Dobhar-chù ("water dog") and Righ nàn Dobhran ("king of the water" or "river"), appears to have been a soul form. When one was killed a man or a woman died. The king otter was supposed to have a jewel in its head like the Indian nāga (serpent deity), the Chinese dragon, the toad, &c. The king otter was invulnerable except on one white spot below its chin. Those who wore a piece of its skin as a charm were supposed to be protected against injury in battle. Evidently, therefore, the otter was originally a god like the boar, the image of which, as Tacitus records, was worn for protection by the Baltic amber searchers of Celtic speech. The biasd na srogaig ("the beast of the lowering horn") was a Hebridean loch dragon with a single horn on its head; this unicorn was tall and clumsy.

The "double" or external soul might also exist in a tree. Both in England and Scotland there are stories of trees withering when some one dies, or of some one dying when trees are felled. Aubrey tells that when the Earl of Winchelsea began to cut down an oak grove near his seat at Eastwell in Kent, the Countess died suddenly, and then his eldest son, Lord Maidstone, was killed at sea. Allan Ramsay, the Scottish poet, tells that the Edgewell tree near Dalhousie Castle was fatal to the family from which he was descended, and Sir Walter Scott refers to it in his "Journal", under the date 13th May, 1829. When a branch fell from it in July, 1874, an old forester exclaimed "The laird's deed noo!" and word was received not long afterwards of the death of the eleventh Earl of Dalhousie. Souls of giants were supposed to be hidden in thorns, eggs, fish, swans, &c. At Fasnacloich, in Argyllshire, the visit of swans to a small loch is supposed to herald the death of a Stewart.

"External souls", or souls after death, assumed the forms of cormorants, cuckoos, cranes, eagles, gulls, herons, linnets, magpies, ravens, swans, wrens, &c., or of deer, mice, cats, dogs, &c. Fairies (supernatural beings) appeared as deer or birds. Among the Scottish were-animals are cats, black sheep, mice, hares, gulls, crows, ravens, magpies, foxes, dogs, &c. Children were sometimes transformed by magicians into white dogs, and were restored to human form by striking them with a magic wand or by supplying shirts of bog-cotton. The floating lore regarding were-animals was absorbed in witch-lore after the Continental beliefs regarding witches were imported into this country. In like manner a good deal of floating lore was attached to the devil. In Scotland he is supposed to appear as a goat or pig, as a gentleman with a pig's or horse's foot, or as a black or green man riding a black or green horse followed by black or green dogs. Eels were "devil-fish", and were supposed to originate from the hairs of horses' manes or tails. Men who ate eels became insane, and fought horses.

In Scotland butterflies and bees were not only soul-forms but deities, and there are traces of similar beliefs in England, Wales, and Ireland. Scottish Gaelic names of the butterfly include dealbhan-dé ("image" or "form of God"), dealbh signifying "image", "form", "picture", "idol", or "statue"; dearbadan-dé ("manifestation of God"); eunan-dé ("small bird of God"); teine-dé ("fire of God"); and dealan-dé ("brightness of God"). The word dealan refers to (1) lightning, (2) the brightness of the starry sky, (3) burning coal, (4) the wooden bar of a door, and (5) to a wooden peg fastening a cow-halter round the neck. The bar and peg, which gave security, were evidently connected with the deity.

In addition to meaning butterfly, dealan-dé ("the dealan of God") refers to a burning stick which is shaken to and fro or whirled round about. When "need fires" (new fires) were lit at Beltain festival (1st May)—"Beltain" is supposed to mean "bright fires" or "white fires", that is, luck-bringing or sacred fires—burning brands were carried from them to houses, all domestic fires having previously been extinguished. The "new fire" brought luck, prosperity, health, increase, protection, &c. Until recently Highland boys who perpetuated the custom of lighting bon-fires to celebrate old Celtic festivals were wont to snatch burning sticks from them and run homewards, whirling the dealan-dé round about so as to keep it burning.

Souls took the form of a dealan-dé (butterfly). Lady Wilde relates in Ancient Legends (Vol. I, pp. 66-7) the Irish story of a child who saw the butterfly form of the soul—"a beautiful living creature with four snow-white wings"; it rose from the body of a man who had just died and went "fluttering round his head". The child and others watched the winged soul "until it passed from sight into the clouds". The story continues: "This was the first butterfly that was ever seen in Ireland; and now all men know that the butterflies are the souls of the dead waiting for the moment when they may enter Purgatory, and so pass through torture to purification and peace".

In England and Scotland moths were likewise souls of the dead that entered houses by night or fluttered outside windows, as if attempting to return to former haunts.

The butterfly god or soul-form was known to the Scandinavians. Freyja, the northern goddess, appears to have had a butterfly avatar. At any rate, the butterfly was consecrated to her. In Greece the nymph Psyche, beloved by Cupid, was a beautiful maiden with the wings of a butterfly; her name signifies "the soul". Greek artistes frequently depicted the human soul as a butterfly, and especially the particular species called ψυχη ("the soul"). On an ancient tomb in Italy a butterfly is shown issuing from the open mouth of a death-mask. The Serbians believed that the butterfly souls of witches arose from their mouths when they slept. They died if their butterfly souls did not return.177 Evidence of belief in the butterfly soul has been forthcoming in Burmah, where ceremonies are performed to prevent the baby's butterfly soul following that of a dead mother.178 The pre-Columbian Americans, and especially the Mexicans, believed in butterfly souls and butterfly deities. In China the butterfly soul was carved in jade and associated with the plum tree;179 the sacred butterfly was in Scotland associated apparently with the honeysuckle (deoghalag), a plant containing "life-substance" in the form of honey (lus a mheahl: "honey herb") and milk (another name of the plant being bainne-ghamhnach: "milk of the heifer"). As we have seen, the honeysuckle was supposed to be more powerful than the tree to which it clung; like the ivy and mistletoe, it was the plant of a powerful deity. Its milk and honey names connect it with the Great Mother goddess who was the source of life and nourishment, and provided the milk-and-honey elixir of life.