полная версия

полная версияAncient Man in Britain

One of the latest references to pagan religious customs is found in the records of Dingwall Presbytery dating from 1649 to 1678. In the Parish of Gairloch, Ross-shire, bulls were sacrificed, oblations of milk were poured on the hills, wells were adored, and chapels were "circulated"—the worshippers walked round them sunwise. Those who intended to set out on journeys thrust their heads into a hole in a stone.118 If a head entered the hole, it was believed the man would return; if it did not, his luck was doubtful. The reference to "oblations of milk" is of special interest, because milk was offered to the fairies. A milk offering was likewise poured daily into the "cup" of a stone known as Clach-na-Gruagach (the stone of the long-haired one). A bowl of milk was, in the Highlands, placed beside a corpse, and, after burial took place, either outside the house door or at the grave. The conventionalized Azilian human form is sometimes found to be depicted by small "cups" on boulders or rocks. Some "cups" were formed by "knocking" with a small stone for purposes of divination. The "cradle stone" at Burghead is a case in point. It is dealt with by Sir Arthur Mitchell (The Past in the Present, pp. 263-5), who refers to other "cup-stones" that were regarded as being "efficacious in cases of barrenness". In some hollowed stones Highland parents immersed children suspected of being changelings.

A flood of light has been thrown on the origin of Druidism by Siret,119 the discoverer of the settlements of Easterners in Spain which have been dealt with in an earlier chapter. He shows that the colonists were an intensely religious people, who introduced the Eastern Palm-tree cult and worshipped a goddess similar to the Egyptian Hathor, a form of whom was Nut. After they were expelled from Spain by a bronze-using people, the refugees settled in Gaul and Italy, carrying with them the science and religious beliefs and practices associated with Druidism. Commercial relations were established between the Etruscans, the peoples of Gaul and the south of Spain, and with the Phœnicians of Tyre and Carthage during the archæological Early Iron Age. Some of the megalithic monuments of North Africa were connected with this later drift.

The goddess Hathor of Egypt was associated with the sycamore fig which exudes a milk-like fluid, with a sea-shell, with the sky (as Nut she was depicted as a star-spangled woman), and with the primeval cow. The tree cult was introduced into Rome. The legend of the foundation of that city is closely associated with the "milk"-yielding fig tree, under which the twins Romulus and Remus were nourished by the wolf. The fig-milk was regarded as an elixir and was given by the Greeks to newly born children.

Siret shows that the ancient name of the Tiber was Rumon, which was derived from the root signifying milk. It was supposed to nourish the earth with terrestrial milk. From the same root came the name of Rome. The ancient milk-providing goddess of Rome was Deva Rumina. Offerings of milk instead of wine were made to her. The starry heavens were called "Juno's milk" by the Romans, and "Hera's milk" by the Greeks, and the name "Milky Way" is still retained.

The milk tree of the British Isles is the hazel. It contains a milky fluid in the green nut, which Highland children of a past generation regarded as a fluid that gave them strength. Nut-milk was evidently regarded in ancient times as an elixir like fig-milk.120 There is a great deal of Gaelic lore connected with the hazel. In Keating's History of Ireland (Vol. I, section 12) appears the significant statement, "Coll (the hazel) indeed was god to MacCuil". "Coll" is the old Gaelic word for hazel; the modern word is "Call". "Calltuinn" (Englished "Calton") is a "hazel grove". There are Caltons in Edinburgh and Glasgow and well-worn forms of the ancient name elsewhere. In the legends associated with the Irish Saint Maedóg is one regarding a dried-up stick of hazel which "sprouted into leaf and blossom and good fruit". It is added that this hazel "endures yet (a.d. 624), a fresh tree, undecayed, unwithered, nut-laden yearly".121 The sacred hazel was supposed to be impregnated with the substance of life. Another reference is made to Coll na nothar ("hazel of the wounded"). Hazel-nuts of longevity, as well as apples of longevity, were supposed to grow in the Gaelic Paradise. In a St. Patrick legend a youth comes from the south ("south" is Paradise and "north" is hell) carrying "a double armful of round yellow-headed nuts and of beautiful golden-yellow apples". Dr. Joyce states that the ancient Irish "attributed certain druidical or fairy virtues to the yew, the hazel, and the quicken or rowan tree", and refers to "innumerable instances in tales, poems, and other old records, in such expressions as 'Cruachan of the fair hazels', 'Derry-na-nath, on which fair-nutted hazels are constantly found'.... Among the blessings a good king brought on the land was plenty of hazel-nuts:—'O'Berga (the chief) for whom the hazels stoop', 'Each hazel is rich from the hero'." Hazel-nuts were like the figs and dates of the Easterners, largely used for food.122

Important evidence regarding the milk elixir and the associated myths and doctrines is preserved in the ancient religious literature of India and especially in the Mahá-bhárata. The Indian Hathor is the cow-mother Surabhi, who sprang from Amrita (Soma) in the mouth of the Grandfather (Brahma). A single jet of her milk gave origin to "Milky Ocean". The milk "mixing with the water" appeared as foam, and was the only nourishment of the holy men called "Foam drinkers". Divine milk was also obtained from "milk-yielding trees", which were the "children" of one of her daughters. These trees included nut trees. Another daughter was the mother of birds of the parrot species (oracular birds). In the Vedic poems soma, a drink prepared from a plant, is said to have been mixed with milk and honey, and mention is made of "Su-soma" ("river of Soma"). Madhu (mead) was a drink identified with soma, or milk and honey.123

There are rivers of mead in the Celtic Paradise. Certain trees are in Irish lore associated with rivers that were regarded as sacred. These were not necessarily milk-yielding trees. In Gaul the plane tree took the place of the southern fig tree. The elm tree in Ireland and Scotland was similarly connected with the ancient milk cult. One of the old names for new milk, found in "Cormac's Glossary", is lemlacht, the later form of which is leamhnacht. From the same root (lem) comes leamh, the name of the elm. The River Laune in Killarney is a rendering of the Gaelic name leamhain, which in Scotland is found as Leven, the river that gave its name to the area known as Lennox (ancient Leamhna). Milk place-names in Ireland include "new milk lake" (Lough Alewnaghta) in Galway, "which", Joyce suggests, "may have been so called from the softness of its water". A mythological origin of the name is more probable. Wounds received in battle were supposed to be healed in baths of the milk of white hornless cows.124 In Irish blood-covenant ceremonies new milk, blood, and wine were mixed and drunk by warriors.125 As late as the twelfth century a rich man's child was in Ireland immersed immediately after birth in new milk.126 In Rome, in the ninth century, at the Easter-eve baptism the chalice was filled "not with wine but with milk and honey, that they may understand … that they have entered already upon the promised land".127

The beliefs associated with the apple, rowan, hazel, and oak trees were essentially the same. These trees provided the fruits of longevity and knowledge, or the wine which was originally regarded as an elixir that imparted new life and inspired those who drank it to prophecy128. The oak provided acorns which were eaten. Although it does not bear red berries like the rowan, a variety of the oak is greatly favoured by the insect Kermes, "which yields a scarlet dye nearly equal to cochineal, and is the 'scarlet' mentioned in Scripture". This fact is of importance as the early peoples attached much value to colour and especially to red, the colour of life blood. Withal, acorn-cups "are largely imported from the Levant for the purposes of tanning, dyeing, and making ink".129 A seafaring people like the ancient Britons must have tanned the skins used for boats so as to prevent them rotting on coming into contact with water. Dr. Joyce writes of the ancient Irish in this connection, "Curraghs130 or wicker-boats were often covered with leather. A jacket of hard, tough, tanned leather was sometimes worn in battle as a protecting corslet. Bags made of leather, and often of undressed skins, were pretty generally used to hold liquids. There was a sort of leather wallet or bag called crioll, used like a modern travelling bag, to hold clothes and other soft articles. The art of tanning was well understood in ancient Ireland. The name for a tanner was sudaire, which is still a living word. Oak bark was employed, and in connection with this use was called coirteach (Latin, cortex)." The oak-god protected seafarers by making their vessels sea-worthy.

Mistletoe berries may have been regarded as milk-berries because of their colour, and the ceremonial cutting of the mistletoe with the golden sickle may well have been a ceremony connected with the fertilization of trees practised in the East. The mistletoe was reputed to be an "all-heal", although really it is useless for medicinal purposes.

That complex ideas were associated with deities imported into this country, the history of which must be sought for elsewhere, is made manifest when we find that, in the treeless Outer Hebrides, the goddess known as the "maiden queen" has her dwelling in a tree and provides the "milk of knowledge" from a sea-shell. She could not possibly have had independent origin in Scotland. Her history is rooted in ancient Egypt, where Hathor, the provider of the milk of knowledge and longevity, was, as has been indicated, connected with the starry sky (the Milky Way), a sea-shell, the milk-yielding sycamore fig, and the primeval cow.

The cult animal of the goddess was in Egypt the star-spangled cow; in Troy it was a star-spangled sow131. The cult animal of Rome was the wolf which suckled Romulus and Remus. In Crete the local Zeus was suckled, according to the belief of one cult, by a horned sheep132, and according to another cult by a sow. There were various cult animals in ancient Scotland, including the tabooed pig, the red deer milked by the fairies, the wolf, and the cat of the "Cat" tribes in Shetland, Caithness, &c. The cow appears to have been sacred to certain peoples in ancient Britain and Ireland. It would appear, too, that there was a sacred dog in Ireland.133

It is evident that among the Eastern beliefs anciently imported into the British Isles were some which still bear traces of the influence of cults and of culture mixing. That religious ideas of Egyptian and Babylonian origin were blended in this country there can be little doubt, for the Gaelic-speaking peoples, who revered the hazel as the Egyptians revered the sycamore, regarded the liver as the seat of life, as did the Babylonians, and not the heart, as did the Egyptians. In translations of ancient Gaelic literature "liver" is always rendered as "vitals".

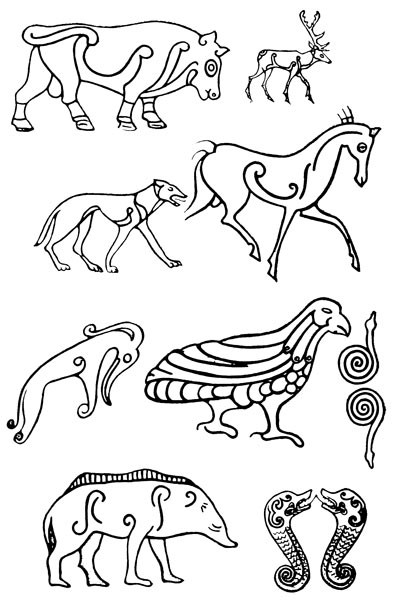

Cult Animals and "Wonder Beasts" (dragons or makaras) on Scottish Sculptured Stones

It is of special interest to note that Siret has found evidence to show that the Tree Cult of the Easterners was connected with the early megalithic monuments. The testimony of tradition associates the stone circles, &c., with the Druids. "We are now obliged", he writes134, "to go back to the theory of the archæologists of a hundred years ago who attributed the megalithic monuments to the Druids. The instinct of our predecessors has been more penetrating than the scientific analysis which has taken its place." In Gaelic, as will be shown, the words for a sacred grove and the shrine within a grove are derived from the same root nem. (See also Chapter IX in this connection.)

CHAPTER XIII

The Lore of Charms

The Meaning of "Luck"—Symbolism of Charms—Colour Symbolism—Death as a Change—Food and Charms for the Dead—The Lucky Pearl—Pearl Goddess—Moon as "Pearl of Heaven"—Sky Goddess connected with Pearls, Groves, and Wells—Night-shining Jewels—Pearl and Coral as "Life Givers"—The Morrigan and Morgan le Fay—Goddess Freyja and Jewels—Amber connected with Goddess and Boar—"Soul Substance" in Amber, Jet, Coral, &c.—Enamel as Substitute for Coral, &c.—Precious Metal and Precious Stones—Goddess of Life and Law—Pearl as a Standard of Value in Gaelic Trade.

Our ancestors were greatly concerned about their luck. They consulted oracles to discover what luck was in store for them. To them luck meant everything they most desired—good health, good fortune, an abundant food supply, and protection against drowning, wounds in battle, accidents, and so on. Luck was ensured by performing ceremonies and wearing charms. Some ceremonies were performed round sacred bon-fires (bone fires), when sacrifices were made, at holy wells, in groves, or in stone circles. Charms included precious stones, coloured stones, pearls, and articles of silver, gold, or copper of symbolic shape, or bearing an image or inscription. Mascots, "lucky pigs", &c., are relics of the ancient custom of wearing charms.

The colour as well as the shape of a charm revealed its particular influence. Certain colours are still regarded as being lucky or unlucky ("yellow is forsaken" some say). In ancient times colours meant much to the Britons, as they did to other peoples. This fact is brought out in many tales and customs. A Welsh story, for instance, which refers to the appearance of supernatural beings attired in red and blue, says, "The red on the one part signifies burning, and the blue on the other signifies coldness".135

On their persisting belief in luck were based the religious ideas and practices of the ancient Britons. Their chief concern was to protect and prolong life in this world and in the next. When death came it was regarded as "a change". The individual was supposed either to fall asleep, or to be transported in the body to Paradise, or to assume a new form. In Scottish Gaelic one can still hear the phrase chaochail e ("he changed") used to signify that "he died".136 But after death charms were as necessary as during life. As in Aurignacian times, luck-charms in the form of necklaces, armlets, &c., were placed in the graves of the dead by those who used flint, or bronze, or iron to shape implements and weapons. The dead had to receive nourishment, and clay vessels are invariably found in ancient graves, some of which contain dusty deposits. The writer has seen at Fortrose a deposit in one of these grave urns, which a medical man identified as part of the skeleton of a bird.

Necklaces of shells, of wild animals' teeth, and ornaments of ivory found in Palæolithic graves or burial caves were connected with the belief that they contained the animating influence or "life substance" of the mother goddess. In later times the pearl found in the shell was regarded as being specially sacred.

Venus (Aphrodite) is, in one of her phases, the personification of a pearl, and is lifted from the sea seated on a shell. As a sky deity she was connected with the planet that bears her name137 and also with the moon. The ancients connected the moon with the pearl. In some languages the moon is the "pearl of heaven". Dante, in his Inferno, refers to the moon as "the eternal pearl". One of the Gaelic names for a pearl is neamhnuid. The root is nem of neamh, and neamh is "heaven", so that the pearl is "a heavenly thing" in Gaelic, as in other ancient languages. It was associated not only with the sky goddess but with the sacred grove in which the goddess was worshipped. The Gaulish name nemeton, of which the root is likewise nem, means "shrine in a grove". In early Christian times in Ireland the name was applied as nemed to a chapel, and in Scottish place-names138 it survives in the form of neimhidh, "church-land", the Englished forms of which are Navity, near Cromarty, Navaty in Fife, "Rosneath", formerly Rosneveth (the promontory of the nemed), "Dalnavie" (dale of the nemed), "Cnocnavie" (hillock of the nemed), Inchnavie (island of the nemed), &c. The Gauls had a nemetomarus ("great shrine"), and when in Roman times a shrine was dedicated to Augustus it was called Augustonemeton. The root nem is in the Latin word nemus (a grove). It was apparently because the goddess of the grove was the goddess of the sky and of the pearl, and the goddess of battle as well as the goddess of love, that Julius Cæsar made a thanksgiving offering to Venus in her temple at Rome of a corslet of British pearls.

The Irish goddess Nemon was the spouse of the war god Neit. A Roman inscription at Bath refers to the British goddess Nĕmĕtŏna. The Gauls had a goddess of similar name. In Galatia, Asia Minor, the particular tree connected with the sky goddess was the oak, as is shown by the name of their religious centre which was Dru-nemeton ("Oak-grove"). It will be shown in a later chapter that the sacred tree was connected with the sky and the deities of the sky, with the sacred wells and rivers, with the sacred fish, and with the fire, the sun, and lightning. Here it may be noted that the sacred well is connected with the holy grove, the sky, the pearl, and the mother goddess in the Irish place-name Neamhnach (Navnagh),139 applied to the well from which flows the stream of the Nith. The well is thus, like the pearl, "the heavenly one". The root nem of neamh (heaven) is found in the name of St. Brendan's mother, who was called Neamhnat (Navnat), which means "little" or "dear heavenly one". In neamhan ("raven" and "crow") the bird form of the deity is enshrined.

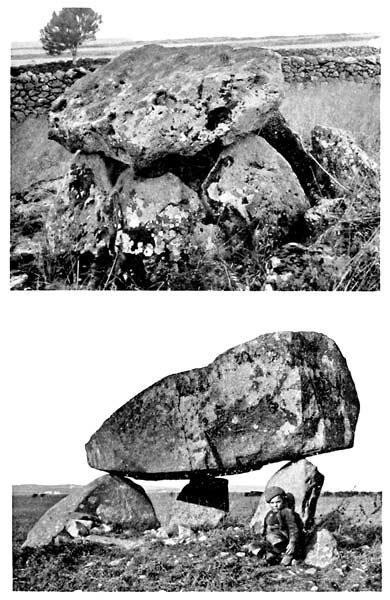

Upper picture by courtesy of Director, British School of Rome

MEGALITHS

Upper: Dolmen near Birori, Sardinia. Lower: Tynewydd Dolmen.

Owing to its connection with the moon, the pearl was supposed to shine by night. The same peculiarity was attributed to certain sacred stones, to coral, jade, &c., and to ivory. Munster people perpetuate the belief that "at the bottom of the lower lake of Killarney there is a diamond of priceless value, which sometimes shines so brightly that on certain nights the light bursts forth with dazzling brilliancy through the dark waters".140 Night-shining jewels are known in Scotland. One is suppose to shine on Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh, and another on the north "souter" of the Cromarty Firth.141 Another sacred stone connected with the goddess was the onyx, which in ancient Gaelic is called nem. Night-shining jewels are referred to in the myths of Greece, Arabia, Persia, India, China, Japan, &c. Laufer has shown that the Chinese received their lore about the night-shining diamond from "Fu-lin" (the Byzantine Empire).142

The ancient pearl-fishers spread their pearl-lore far and wide. It is told in more than one land that pearls are formed by dew-drops from the sky. Pliny says the dew-or rain-drops fall into the shells of the pearl-oyster when it gapes.143 In modern times the belief is that pearls are the congealed tears of the angels. In Greece the pearl was called margaritoe, a name which survives in Margaret, anciently the name of a goddess. The old Persian name for pearl is margan, which signifies "life giver". It is possible that this is the original meaning of the name of Morgan le Fay (Morgan the Fairy), who is remembered as the sister of King Arthur, and of the Irish goddess Morrigan, usually Englished as "Sea-queen" (the sea as the source of life), or "great queen". At any rate, Morgan le Fay and the Morrigan closely resemble one another. In Italian we meet with Fata Morgana.

The old Persian word for coral is likewise margan. Coral was supposed to be a tree, and it was regarded as the sea-tree of the sea and sky goddess. Amber was connected, too, with the goddess. In northern mythology, amber, pearls, precious stones, and precious metals were supposed to be congealed forms of the tears of the goddess Freyja, the Venus of the Scandinavians.

Amber, like pearls, was sacred to the mother goddess because her life substance (the animating principle) was supposed to be concentrated in it. The connection between the precious or sacred amber and the goddess and her cult animal is brought out in a reference made by Tacitus to the amber collectors and traders on the southern shore of the Baltic. These are the Æstyans, who, according to Tacitus, were costumed like the Swedes, but spoke a language resembling the dialect of the Britons. "They worship", the historian records, "the mother of the gods. The figure of a wild boar is the symbol of their superstition; and he who has that emblem about him thinks himself secure even in the thickest ranks of the enemy without any need of arms or any other mode of defence."144 The animal of the amber goddess was thus the boar, which was the sacred animal of the Celtic tribe, the Iceni of ancient Britain, which under Boadicea revolted against Roman rule. The symbol of the boar (remembered as the "lucky pig") is found on ancient British armour. On the famous Witham shield there are coral and enamel. Three bronze boar symbols found in a field at Hounslow are preserved in the British Museum. In the same field was found a solar-wheel symbol. "The boar frequently occurs in British and Gaulish coins of the period, and examples have been found as far off as Gurina and Transylvania."145 Other sacred cult animals were connected with the goddess by those people who fished for pearls and coral or searched for sacred precious stones or precious metals.

At the basis of the ancient religious system that connected coral, shells, and pearls with the mother goddess of the sea, wells, rivers, and lakes, was the belief that all life had its origin in water. Pearls, amber, marsh plants, and animals connected with water were supposed to be closely associated with the goddess who herself had had her origin in water. Tacitus tells that the Baltic worshippers of the mother goddess called amber glesse. According to Pliny146 it was called glessum by the Germans, and he tells that one of the Baltic islands famous for its amber was named Glessaria. The root is the Celtic word glas, which originally meant "water" and especially life-giving water. Boece (Cosmographie, Chapter XV) tells that in Scotland the belief prevailed that amber was generated of sea-froth. It thus had its origin like Aphrodite. Glas is now a colour term in Welsh and Gaelic, signifying green or grey, or even a shade of blue. It was anciently used to denote vigour, as in the term Gaidheal glas ("the vigorous Gael" or "the ambered Gael", the vigour being derived from the goddess of amber and the sea); and in the Latinized form of the old British name Cuneglasos, which like the Irish Conglas signified "vigorous hound".147 Here the sacred hound figures in place of the sacred boar.

From the root glas comes also glaisin, the Gaelic name for woad, the blue dyestuff with which ancient Britons and Gaels stained or tattooed their bodies with figures of sacred animals or symbols,148 apparently to secure protection as did those who had the boar symbol on their armour. For the same reason Cuchullin, the Irish Achilles, wore pearls in his hair, and the Roman Emperor Caligula had a pearl collar on his favourite horse. Ice being a form of water is in French glacé, which also means "glass". When glass beads were first manufactured they were regarded, like amber, as depositories of "life substance" from the water goddess who, as sky goddess, was connected with sun and fire. Her fire melted the constituents of glass into liquid form, and it hardened like jewels and amber. These beads were called "adder stones" (Welsh glain neidre and "Druid's gem" or "glass"—in Welsh Gleini na Droedh and in Gaelic Glaine nan Druidhe).