полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 6 (of 9)

TO MR. MILES KING

Monticello, September 26, 1814.Sir,—I duly received your letter of August 20th, and I thank you for it, because I believe it was written with kind intentions, and a personal concern for my future happiness. Whether the particular revelation which you suppose to have been made to yourself were real or imaginary, your reason alone is the competent judge. For dispute as long as we will on religious tenets, our reason at last must ultimately decide, as it is the only oracle which God has given us to determine between what really comes from him and the phantasms of a disordered or deluded imagination. When he means to make a personal revelation, he carries conviction of its authenticity to the reason he has bestowed as the umpire of truth. You believe you have been favored with such a special communication. Your reason, not mine, is to judge of this; and if it shall be his pleasure to favor me with a like admonition, I shall obey it with the same fidelity with which I would obey his known will in all cases. Hitherto I have been under the guidance of that portion of reason which he has thought proper to deal out to me. I have followed it faithfully in all important cases, to such a degree at least as leaves me without uneasiness; and if on minor occasions I have erred from its dictates, I have trust in him who made us what we are, and know it was not his plan to make us always unerring. He has formed us moral agents. Not that, in the perfection of his state, he can feel pain or pleasure in anything we may do; he is far above our power; but that we may promote the happiness of those with whom he has placed us in society, by acting honestly towards all, benevolently to those who fall within our way, respecting sacredly their rights, bodily and mental, and cherishing especially their freedom of conscience, as we value our own. I must ever believe that religion substantially good which produces an honest life, and we have been authorized by one whom you and I equally respect, to judge of the tree by its fruit. Our particular principles of religion are a subject of accountability to our God alone. I inquire after no man's, and trouble none with mine; nor is it given to us in this life to know whether yours or mine, our friends or our foes, are exactly the right. Nay, we have heard it said that there is not a Quaker or a Baptist, a Presbyterian or an Episcopalian, a Catholic or a Protestant in heaven; that, on entering that gate, we leave those badges of schism behind, and find ourselves united in those principles only in which God has united us all. Let us not be uneasy then about the different roads we may pursue, as believing them the shortest, to that our last abode; but, following the guidance of a good conscience, let us be happy in the hope that by these different paths we shall all meet in the end. And that you and I may there meet and embrace, is my earnest prayer. And with this assurance I salute you with brotherly esteem and respect.

TO JOSEPH C. CABELL, ESQ

Monticello, September 30, 1814.Dear Sir,—In my letter of the 23d, an important fact escaped me which, lest it should not occur to you, I will mention. The monies arising from the sales of the glebe lands in the several counties, have generally, I believe, and under the sanction of the legislature, been deposited in some of the banks. So also the funds of the literary society. These debts, although parcelled among the counties, yet the counties constitute the State, and their representatives the legislature, united into one whole. It is right then that owing $300,000 to the banks, they should stay so much of that sum in their own hands as will secure what the banks owe to their constituents as divided into counties. Perhaps the loss of these funds would be the most lasting of the evils proceeding from the insolvency of the banks. Ever yours with great esteem and respect.

TO THOMAS COOPER, ESQ

Monticello, October 7, 1814.Dear Sir,—Your several favors of September 15th, 21st, 22d, came all together by our last mail. I have given to that of the 15th a single reading only, because the hand writing (not your own) is microscopic and difficult, and because I shall have an opportunity of studying it in the Portfolio in print. According to your request I return it for that publication, where it will do a great deal of good. It will give our young men some idea of what constitutes a well-educated man; that Cæsar and Virgil, and a few books of Euclid, do not really contain the sum of all human knowledge, nor give to a man figure in the ranks of science. Your letter will be a valuable source of consultation for us in our Collegiate courses, when, and if ever, we advance to that stage of our establishment.

I agree with yours of the 22d, that a professorship of Theology should have no place in our institution. But we cannot always do what is absolutely best. Those with whom we act, entertaining different views, have the power and the right of carrying them into practice. Truth advances, and error recedes step by step only; and to do to our fellow-men the most good in our power, we must lead where we can, follow where we can not, and still go with them, watching always the favorable moment for helping them to another step. Perhaps I should concur with you also in excluding the theory (not the practice) of medicine. This is the charlatanerie of the body, as the other is of the mind. For classical learning I have ever been a zealous advocate; and in this, as in his theory of bleeding and mercury, I was ever opposed to my friend Rush, whom I greatly loved; but who has done much harm, in the sincerest persuasion that he was preserving life and happiness to all around him. I have not, however, carried so far as you do my ideas of the importance of a hypercritical knowledge of the Latin and Greek languages. I have believed it sufficient to possess a substantial understanding of their authors.

In the exclusion of Anatomy and Botany from the eleventh grade of education, which is that of the man of independent fortune, we separate in opinion. In my view, no knowledge can be more satisfactory to a man than that of his own frame, its parts, their functions and actions. And Botany I rank with the most valuable sciences, whether we consider its subjects as furnishing the principal subsistence of life to man and beast, delicious varieties for our tables, refreshments from our orchards, the adornments of our flower-borders, shade and perfume of our groves, materials for our buildings, or medicaments for our bodies. To the gentlemen it is certainly more interesting than mineralogy (which I by no means, however, undervalue), and is more at hand for his amusement; and to a country family it constitutes a great portion of their social entertainment. No country gentleman should be without what amuses every step he takes into his fields.

I am sorry to learn the fate of your Emporium. It was adding fast to our useful knowledge. Our artists particularly, and our statesmen, will have cause to regret it. But my hope is that its suspension will be temporary only; and that as soon as we get over the crisis of our disordered circulation, your publishers will resume it among their first enterprises. Accept my thanks for the benefit of your ideas to our scheme of education, and the assurance of my constant esteem and respect.

To – 12

Monticello, October 15, 1814.Dear Sir,—I thank you for the information of your letter of the 10th. It gives, at length, a fixed character to our prospects. The war, undertaken, on both sides, to settle the questions of impressment, and the orders of council, now that these are done away by events, is declared by Great Britain to have changed its object, and to have become a war of conquest, to be waged until she conquers from us our fisheries, the province of Maine, the lakes, States and territories north of the Ohio, and the navigation of the Mississippi; in other words, till she reduces us to unconditional submission. On our part, then, we ought to propose, as a counterchange of object, the establishment of the meridian of the mouth of the Sorel northwardly, as the western boundary of all her possessions. Two measures will enable us to effect it, and without these, we cannot even defend ourselves. 1. To organize the militia into classes, assigning to each class the duties for which it is fitted, (which, had it been done when proposed, years ago, would have prevented all our misfortunes,) abolishing by a declaratory law the doubts which abstract scruples in some, and cowardice and treachery in others, have conjured up about passing imaginary lines, and limiting, at the same time, their services to the contiguous provinces of the enemy. The 2d is the ways and means. You have seen my ideas on this subject, and I shall add nothing but a rectification of what either I have ill expressed, or you have misapprehended. If I have used any expression restraining the emissions of treasury notes to a sufficient medium, as your letter seems to imply, I have done it inadvertently, and under the impression then possessing me, that the war would be very short. A sufficient medium would not, on the principles of any writer, exceed thirty millions of dollars, and on those of some not ten millions. Our experience has proved it may be run up to two or three hundred millions, without more than doubling what would be the prices of things under a sufficient medium, or say a metallic one, which would always keep itself at the sufficient point; and, if they rise to this term, and the descent from it be gradual, it would not produce sensible revolutions in private fortunes. I shall be able to explain my views more definitely by the use of numbers. Suppose we require, to carry on the war, an annual loan of twenty millions, then I propose that, in the first year, you shall lay a tax of two millions, and emit twenty millions of treasury notes, of a size proper for circulation, and bearing no interest, to the redemption of which the proceeds of that tax shall be inviolably pledged and applied, by recalling annually their amount of the identical bills funded on them. The second year lay another tax of two millions, and emit twenty millions more. The third year the same, and so on, until you have reached the maximum of taxes which ought to be imposed. Let me suppose this maximum to be one dollar a head, or ten millions of dollars, merely as an exemplification more familiar than would be the algebraical symbols x or y. You would reach this in five years. The sixth year, then, still emit twenty millions of treasury notes, and continue all the taxes two years longer. The seventh year twenty millions more, and continue the whole taxes another two years; and so on. Observe, that although you emit ten millions of dollars a year, you call in ten millions, and, consequently, add but ten millions annually to the circulation. It would be in thirty years, then, primâ facie, that you would reach the present circulation of three hundred millions, or the ultimate term to which we might adventure. But observe, also, that in that time we shall have become thirty millions of people to whom three hundred millions of dollars would be no more than one hundred millions to us now; which sum would probably not have raised prices more than fifty per cent. on what may be deemed the standard, or metallic prices. This increased population and consumption, while it would be increasing the proceeds of the redemption tax, and lessening the balance annually thrown into circulation, would also absorb, without saturation, more of the surplus medium, and enable us to push the same process to a much higher term, to one which we might safely call indefinite, because extending so far beyond the limits, either in time or expense, of any supportable war. All we should have to do would be, when the war should be ended, to leave the gradual extinction of these notes to the operation of the taxes pledged for their redemption; not to suffer a dollar of paper to be emitted either by public or private authority, but let the metallic medium flow back into the channels of circulation, and occupy them until another war should oblige us to recur, for its support, to the same resource, and the same process, on the circulating medium.

The citizens of a country like ours will never have unemployed capital. Too many enterprises are open, offering high profits, to permit them to lend their capitals on a regular and moderate interest. They are too enterprizing and sanguine themselves not to believe they can do better with it. I never did believe you could have gone beyond a first or a second loan, not from a want of confidence in the public faith, which is perfectly sound, but from a want of disposable funds in individuals. The circulating fund is the only one we can ever command with certainty. It is sufficient for all our wants; and the impossibility of even defending the country without its aid as a borrowing fund, renders it indispensable that the nation should take and keep it in their own hands, as their exclusive resource.

I have trespassed on your time so far, for explanation only. I will do it no further than by adding the assurances of my affectionate and respectful attachment.

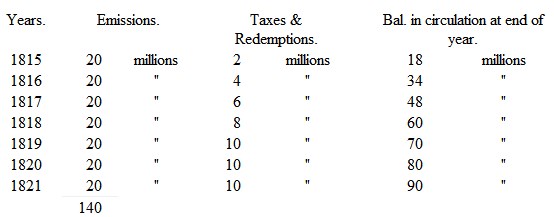

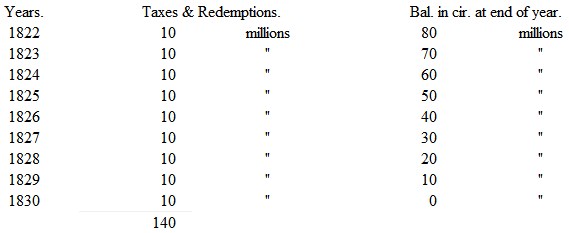

Suppose the war to terminate here, to wit, at the end of seven years, the reduction will proceed as follows:

This is a tabular statement of the amount of emission, taxes, redemptions, and balances left in circulation every year, on the plan above sketched.

TO JAMES MONROE

Monticello, October 16, 1814.Dear Sir,—Your letter of the 10th has been duly received. The objects of our contest being thus entirely changed by England, we must prepare for interminable war. To this end we should put our house in order, by providing men and money to indefinite extent. The former may be done by classing our militia, and assigning each class to the description of duties for which it is fit. It is nonsense to talk of regulars. They are not to be had among a people so easy and happy at home as ours. We might as well rely on calling down an army of angels from heaven. I trust it is now seen that the refusal to class the militia, when proposed years ago, is the real source of all our misfortunes in this war. The other great and indispensable object is to enter on such a system of finance, as can be permanently pursued to any length of time whatever. Let us be allured by no projects of banks, public or private, or ephemeral expedients, which, enabling us to gasp and flounder a little longer, only increase, by protracting the agonies of death.

Perceiving, in a letter from the President, that either I had ill expressed my ideas on a particular part of this subject, in the letters I sent you, or he had misapprehended them, I wrote him yesterday an explanation; and as you have thought the other letters worth a perusal, and a communication to the Secretary of the Treasury, I enclose you a copy of this, lest I should be misunderstood by others also. Only be so good as to return me the whole when done with, as I have no other copies.

Since writing the letter now enclosed, I have seen the Report of the committee of finance, proposing taxes to the amount of twenty millions. This is a dashing proposition. But, if Congress pass it, I shall consider it sufficient evidence that their constituents generally can pay the tax. No man has greater confidence than I have, in the spirit of the people, to a rational extent. Whatever they can, they will. But, without either market or medium, I know not how it is to be done. All markets abroad, and all at home, are shut to us; so that we have been feeding our horses on wheat. Before the day of collection, bank-notes will be but as oak leaves; and of specie, there is not within all the United States, one-half of the proposed amount of the taxes. I had thought myself as bold as was safe in contemplating, as possible, an annual taxation of ten millions, as a fund for emissions of treasury notes; and, when further emissions should be necessary, that it would be better to enlarge the time, than the tax for redemption. Our position, with respect to our enemy, and our markets, distinguishes us from all other nations; inasmuch, as a state of war, with us, annihilates in an instant all our surplus produce, that on which we depended for many comforts of life. This renders peculiarly expedient the throwing a part of the burdens of war on times of peace and commerce. Still, however, my hope is that others see resources, which, in my abstraction from the world, are unseen by me; that there will be both market and medium to meet these taxes, and that there are circumstances which render it wiser to levy twenty millions at once on the people, than to obtain the same sum on a tenth of the tax.

I enclose you a letter from Colonel James Lewis, now of Tennessee, who wishes to be appointed Indian agent, and I do it lest he should have relied solely on this channel of communication. You know him better than I do, as he was long your agent. I have always believed him an honest man, and very good-humored and accommodating. Of his other qualifications for the office, you are the best judge. Believe me to be ever affectionately yours.

TO DOCTOR ROBERT PATTERSON

Monticello, November 23, 1814.Dear Sir,—I have heretofore confided to you my wishes to retire from the chair of the Philosophical Society, which, however, under the influence of your recommendations, I have hitherto deferred. I have never, however, ceased from the purpose, and from everything I can observe or learn at this distance, I suppose that a new choice can now be made with as much harmony as may be expected at any future time. I send therefore, by this mail, my resignation, with such entreaties to be omitted at the ensuing election as I must hope will be yielded to, for in truth I cannot be easy in holding, as a sinecure, an honor so justly due to the talents and services of others. I pray your friendly assistance in assuring the society of the sentiments of affectionate respect and gratitude with which I retire from the high and honorable relation in which I have stood with them, and that you will believe me to be ever and affectionately yours.

TO ROBERT M. PATTERSON, SECRETARY OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY

Monticello, November 23, 1814.Sir,—I solicited, on a former occasion, permission from the American Philosophical Society, to retire from the honor of their chair, under a consciousness that distance as well as other circumstances, denied me the power of executing the duties of the station, and that those on whom they devolved were best entitled to the honors they confer. It was the pleasure of the society at that time, that I should remain in their service, and they have continued since to renew the same marks of their partiality. Of these I have been ever duly sensible, and now beg leave to return my thanks for them with humble gratitude. Still, I have never ceased, nor can I cease to feel that I am holding honors without yielding requital, and justly belonging to others. As the period of election is now therefore approaching, I take the occasion of begging to be withdrawn from the attention of the society at their ensuing choice, and to be permitted now to resign the office of president into their hands, which I hereby do. I shall consider myself sufficiently honored in remaining a private member of their body, and shall ever avail myself with zeal of every occasion which may occur, of being useful to them, retaining indelibly a profound sense of their past favors.

I avail myself of the channel through which the last notification of the pleasure of the society was conveyed to me, to make this communication, and with the greater satisfaction, as it gratifies me with the occasion of assuring you personally of my high respect for yourself, and of the interest I shall ever take in learning that your worth and talents secure to you the successes they merit.

TO W. SHORT, ESQ

Monticello, November 28, 1814.Dear Sir,—Yours of October 28th came to hand on the 15th instant only. The settlement of your boundary with Colonel Monroe, is protracted by circumstances which seem foreign to it. One would hardly have expected that the hostile expedition to Washington could have had any connection with an operation one hundred miles distant. Yet preventing his attendance, nothing could be done. I am satisfied there is no unwillingness on his part, but on the contrary a desire to have it settled; and therefore, if he should think it indispensable to be present at the investigation, as is possible, the very first time he comes here I will press him to give a day to the decision, without regarding Mr. Carter's absence. Such an occasion must certainly offer soon after the fourth of March, when Congress rises of necessity and be assured I will not lose one possible moment in effecting it.

Although withdrawn from all anxious attention to political concerns, yet I will state my impressions as to the present war, because your letter leads to the subject. The essential grounds of the war were, 1st, the orders of council; and 2d, the impressment of our citizens; (for I put out of sight from the love of peace the multiplied insults on our government and aggressions on our commerce, with which our pouch, like the Indian's, had long been filled to the mouth.) What immediately produced the declaration was, 1st, the proclamation of the Prince Regent that he would never repeal the orders of council as to us, until Bonaparte should have revoked his decrees as to all other nations as well as ours; and 2d, the declaration of his minister to ours that no arrangement whatever could be devised, admissible in lieu of impressment. It was certainly a misfortune that they did not know themselves at the date of this silly and insolent proclamation, that within one month they would repeal the orders, and that we, at the date of our declaration, could not know of the repeal which was then going on one thousand leagues distant. Their determinations, as declared by themselves, could alone guide us, and they shut the door on all further negotiation, throwing down to us the gauntlet of war or submission as the only alternatives. We cannot blame the government for choosing that of war, because certainly the great majority of the nation thought it ought to be chosen, not that they were to gain by it in dollars and cents; all men know that war is a losing game to both parties. But they know also that if they do not resist encroachment at some point, all will be taken from them, and that more would then be lost even in dollars and cents by submission than resistance. It is the case of giving a part to save the whole, a limb to save life. It is the melancholy law of human societies to be compelled sometimes to choose a great evil in order to ward off a greater; to deter their neighbors from rapine by making it cost them more than honest gains. The enemy are accordingly now disgorging what they had so ravenously swallowed. The orders of council had taken from us near one thousand vessels. Our list of captures from them is now one thousand three hundred, and, just become sensible that it is small and not large ships which gall them most, we shall probably add one thousand prizes a year to their past losses. Again, supposing that, according to the confession of their own minister in parliament, the Americans they had impressed were something short of two thousand, the war against us alone cannot cost them less than twenty millions of dollars a year, so that each American impressed has already cost them ten thousand dollars, and every year will add five thousand dollars more to his price. We, I suppose, expend more; but had we adopted the other alternative of submission, no mortal can tell what the cost would have been. I consider the war then as entirely justifiable on our part, although I am still sensible it is a deplorable misfortune to us. It has arrested the course of the most remarkable tide of prosperity any nation ever experienced, and has closed such prospects of future improvement as were never before in the view of any people. Farewell all hopes of extinguishing public debt! farewell all visions of applying surpluses of revenue to the improvements of peace rather than the ravages of war. Our enemy has indeed the consolation of Satan on removing our first parents from Paradise: from a peaceable and agricultural nation, he makes us a military and manufacturing one. We shall indeed survive the conflict. Breeders enough will remain to carry on population. We shall retain our country, and rapid advances in the art of war will soon enable us to beat our enemy, and probably drive him from the continent. We have men enough, and I am in hopes the present session of Congress will provide the means of commanding their services. But I wish I could see them get into a better train of finance. Their banking projects are like dosing dropsy with more water. If anything could revolt our citizens against the war, it would be the extravagance with which they are about to be taxed. It is strange indeed that at this day, and in a country where English proceedings are so familiar, the principles and advantages of funding should be neglected, and expedients resorted to. Their new bank, if not abortive at its birth, will not last through one campaign; and the taxes proposed cannot be paid. How can a people who cannot get fifty cents a bushel for their wheat, while they pay twelve dollars a bushel for their salt, pay five times the amount of taxes they ever paid before? Yet that will be the case in all the States south of the Potomac. Our resources are competent to the maintenance of the war if duly economized and skillfuly employed in the way of anticipation. However, we must suffer, I suppose, from our ignorance in funding, as we did from that of fighting, until necessity teaches us both; and, fortunately, our stamina are so vigorous as to rise superior to great mismanagement. This year I think we shall have learnt how to call forth our force, and by the next I hope our funds, and even if the state of Europe should not by that time give the enemy employment enough nearer home, we shall leave him nothing to fight for here. These are my views of the war. They embrace a great deal of sufferance, trying privations, and no benefit but that of teaching our enemy that he is never to gain by wanton injuries on us. To me this state of things brings a sacrifice of all tranquillity and comfort through the residue of life. For although the debility of age disables me from the services and sufferings of the field, yet, by the total annihilation in value of the produce which was to give me subsistence and independence, I shall be like Tantalus, up to the shoulders in water, yet dying with thirst. We can make indeed enough to eat, drink and clothe ourselves; but nothing for our salt, iron, groceries and taxes, which must be paid in money. For what can we raise for the market? Wheat? we can only give it to our horses, as we have been doing ever since harvest. Tobacco? it is not worth the pipe it is smoked in. Some say Whiskey; but all mankind must become drunkards to consume it. But although we feel, we shall not flinch. We must consider now, as in the revolutionary war, that although the evils of resistance are great, those of submission would be greater. We must meet, therefore, the former as the casualties of tempests and earthquakes, and like them necessarily resulting from the constitution of the world. Your situation, my dear friend, is much better. For, although I do not know with certainty the nature of your investments, yet I presume they are not in banks, insurance companies or any other of those gossamer castles. If in ground-rents, they are solid; if in stock of the United States, they are equally so. I once thought that in the event of a war we should be obliged to suspend paying the interest of the public debt. But a dozen years more of experience and observation on our people and government, have satisfied me it will never be done. The sense of the necessity of public credit is so universal and so deeply rooted, that no other necessity will prevail against it; and I am glad to see that while the former eight millions are steadfastly applied to the sinking of the old debt, the Senate have lately insisted on a sinking fund for the new. This is the dawn of that improvement in the management of our finances which I look to for salvation; and I trust that the light will continue to advance, and point out their way to our legislators. They will soon see that instead of taxes for the whole year's expenses, which the people cannot pay, a tax to the amount of the interest and a reasonable portion of the principal will command the whole sum, and throw a part of the burthens of war on times of peace and prosperity. A sacred payment of interest is the only way to make the most of their resources, and a sense of that renders your income from our funds more certain than mine from lands. Some apprehend danger from the defection of Massachusetts. It is a disagreeable circumstance, but not a dangerous one. If they become neutral, we are sufficient for one enemy without them, and in fact we get no aid from them now. If their administration determines to join the enemy, their force will be annihilated by equality of division among themselves. Their federalists will then call in the English army, the republicans ours, and it will only be a transfer of the scene of war from Canada to Massachusetts; and we can get ten men to go to Massachusetts for one who will go to Canada. Every one, too, must know that we can at any moment make peace with England at the expense of the navigation and fisheries of Massachusetts. But it will not come to this. Their own people will put down these factionists as soon as they see the real object of their opposition; and of this Vermont, New Hampshire, and even Connecticut itself, furnish proofs.