полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 6 (of 9)

With this offering of what occurs to me on the subject of these prints, accept the assurance of my respect.

TO THOMAS COOPER, ESQ

Monticello, September 10, 1814.Dear Sir,—I regret much that I was so late in consulting you on the subject of the academy we wish to establish here. The progress of that business has obliged me to prepare an address to the President of the Board of Trustees,—a plan for its organization. I send you a copy of it with a broad margin, that, if your answer to mine of August 25th be not on the way, you may be so good as to write your suggestions either in the margin or on a separate paper. We shall still be able to avail ourselves of them by way of amendments.

Your letter of August 17th is received. Mr. Ogilvie left us four days ago, on a tour of health, which is to terminate at New York, from whence he will take his passage to Britain to receive livery and seisin of his new dignities and fortunes. I am in the daily hope of seeing M. Corrica, and the more anxious as I must in two or three weeks commence a journey of long absence from home.

A comparison of the conditions of Great Britain and the United States, which is the subject of your letter of August 17th, would be an interesting theme indeed. To discuss it minutely and demonstratively would be far beyond the limits of a letter. I will give you, therefore, in brief only, the result of my reflections on the subject. I agree with you in your facts, and in many of your reflections. My conclusion is without doubt, as I am sure yours will be, when the appeal to your sound judgment is seriously made. The population of England is composed of three descriptions of persons, (for those of minor note are too inconsiderable to affect a general estimate.) These are, 1. The aristocracy, comprehending the nobility, the wealthy commoners, the high grades of priesthood, and the officers of government. 2. The laboring class. 3. The eleemosynary class, or paupers, who are about one-fifth of the whole. The aristocracy, which has the laws and government in their hands, have so managed them as to reduce the third description below the means of supporting life, even by labor; and to force the second, whether employed in agriculture or the arts, to the maximum of labor which the construction of the human body can endure, and to the minimum of food, and of the meanest kind, which will preserve it in life, and in strength sufficient to perform its functions. To obtain food enough, and clothing, not only their whole strength must be unremittingly exerted, but the utmost dexterity also which they can acquire; and those of great dexterity only can keep their ground, while those of less must sink into the class of paupers. Nor is it manual dexterity alone, but the acutest resources of the mind also which are impressed into this struggle for life; and such as have means a little above the rest, as the master-workmen, for instance, must strengthen themselves by acquiring as much of the philosophy of their trade as will enable them to compete with their rivals, and keep themselves above ground. Hence the industry and manual dexterity of their journeymen and day-laborers, and the science of their master-workmen, keep them in the foremost ranks of competition with those of other nations; and the less dexterous individuals, falling into the eleemosynary ranks, furnish materials for armies and navies to defend their country, exercise piracy on the ocean, and carry conflagration, plunder and devastation, on the shores of all those who endeavor to withstand their aggressions. A society thus constituted possesses certainly the means of defence. But what does it defend? The pauperism of the lowest class, the abject oppression of the laboring, and the luxury, the riot, the domination and the vicious happiness of the aristocracy. In their hands, the paupers are used as tools to maintain their own wretchedness, and to keep down the laboring portion by shooting them whenever the desperation produced by the cravings of their stomachs drives them into riots. Such is the happiness of scientific England; now let us see the American side of the medal.

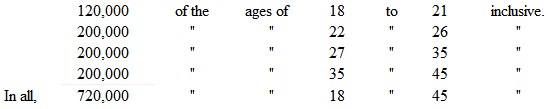

And, first, we have no paupers, the old and crippled among us, who possess nothing and have no families to take care of them, being too few to merit notice as a separate section of society, or to affect a general estimate. The great mass of our population is of laborers; our rich, who can live without labor, either manual or professional, being few, and of moderate wealth. Most of the laboring class possess property, cultivate their own lands, have families, and from the demand for their labor are enabled to exact from the rich and the competent such prices as enable them to be fed abundantly, clothed above mere decency, to labor moderately and raise their families. They are not driven to the ultimate resources of dexterity and skill, because their wares will sell although not quite so nice as those of England. The wealthy, on the other hand, and those at their ease, know nothing of what the Europeans call luxury. They have only somewhat more of the comforts and decencies of life than those who furnish them. Can any condition of society be more desirable than this? Nor in the class of laborers do I mean to withhold from the comparison that portion whose color has condemned them, in certain parts of our Union, to a subjection to the will of others. Even these are better fed in these States, warmer clothed, and labor less than the journeymen or day-laborers of England. They have the comfort, too, of numerous families, in the midst of whom they live without want, or fear of it; a solace which few of the laborers of England possess. They are subject, it is true, to bodily coercion; but are not the hundreds of thousands of British soldiers and seamen subject to the same, without seeing, at the end of their career, when age and accident shall have rendered them unequal to labor, the certainty, which the other has, that he will never want? And has not the British seaman, as much as the African, been reduced to this bondage by force, in flagrant violation of his own consent, and of his natural right in his own person? and with the laborers of England generally, does not the moral coercion of want subject their will as despotically to that of their employer, as the physical constraint does the soldier, the seaman, or the slave? But do not mistake me. I am not advocating slavery. I am not justifying the wrongs we have committed on a foreign people, by the example of another nation committing equal wrongs on their own subjects. On the contrary, there is nothing I would not sacrifice to a practicable plan of abolishing every vestige of this moral and political depravity. But I am at present comparing the condition and degree of suffering to which oppression has reduced the man of one color, with the condition and degree of suffering to which oppression has reduced the man of another color; equally condemning both. Now let us compute by numbers the sum of happiness of the two countries. In England, happiness is the lot of the aristocracy only; and the proportion they bear to the laborers and paupers, you know better than I do. Were I to guess that they are four in every hundred, then the happiness of the nation would be to its misery as one in twenty-five. In the United States it is as eight millions to zero, or as all to none. But it is said they possess the means of defence, and that we do not. How so? Are we not men? Yes; but our men are so happy at home that they will not hire themselves to be shot at for a shilling a day. Hence we can have no standing armies for defence, because we have no paupers to furnish the materials. The Greeks and Romans had no standing armies, yet they defended themselves. The Greeks by their laws, and the Romans by the spirit of their people, took care to put into the hands of their rulers no such engine of oppression as a standing army. Their system was to make every man a soldier, and oblige him to repair to the standard of his country whenever that was reared. This made them invincible; and the same remedy will make us so. In the beginning of our government we were willing to introduce the least coercion possible on the will of the citizen. Hence a system of military duty was established too indulgent to his indolence. This is the first opportunity we have had of trying it, and it has completely failed; an issue foreseen by many, and for which remedies have been proposed. That of classing the militia according to age, and allotting each age to the particular kind of service to which it was competent, was proposed to Congress in 1805, and subsequently; and, on the last trial, was lost, I believe, by a single vote only. Had it prevailed, what has now happened would not have happened. Instead of burning our Capitol, we should have possessed theirs in Montreal and Quebec. We must now adopt it, and all will be safe. We had in the United States in 1805, in round numbers of free, able-bodied men,

With this force properly classed, organized, trained, armed and subject to tours of a year of military duty, we have no more to fear for the defence of our country than those who have the resources of despotism and pauperism.

But, you will say, we have been devastated in the meantime. True, some of our public buildings have been burnt, and some scores of individuals on the tide-water have lost their movable property and their houses. I pity them, and execrate the barbarians who delight in unavailing mischief. But these individuals have their lands and their hands left. They are not paupers, they have still better means of subsistence than 24/25 of the people of England. Again, the English have burnt our Capitol and President's house by means of their force. We can burn their St. James' and St. Paul's by means of our money, offered to their own incendiaries, of whom there are thousands in London who would do it rather than starve. But it is against the laws of civilized warfare to employ secret incendiaries. Is it not equally so to destroy the works of art by armed incendiaries? Bonaparte, possessed at times of almost every capital of Europe, with all his despotism and power, injured no monument of art. If a nation, breaking through all the restraints of civilized character, uses its means of destruction (power, for example) without distinction of objects, may we not use our means (our money and their pauperism) to retaliate their barbarous ravages? Are we obliged to use for resistance exactly the weapons chosen by them for aggression? When they destroyed Copenhagen by superior force, against all the laws of God and man, would it have been unjustifiable for the Danes to have destroyed their ships by torpedoes? Clearly not; and they and we should now be justifiable in the conflagration of St. James' and St. Paul's. And if we do not carry it into execution, it is because we think it more moral and more honorable to set a good example, than follow a bad one.

So much for the happiness of the people of England, and the morality of their government, in comparison with the happiness and the morality of America. Let us pass to another subject.

The crisis, then, of the abuses of banking is arrived. The banks have pronounced their own sentence of death. Between two and three hundred millions of dollars of their promissory notes are in the hands of the people, for solid produce and property sold, and they formally declare they will not pay them. This is an act of bankruptcy of course, and will be so pronounced by any court before which it shall be brought. But cui bono? The law can only uncover their insolvency, by opening to its suitors their empty vaults. Thus by the dupery of our citizens, and tame acquiescence of our legislators, the nation is plundered of two or three hundred millions of dollars, treble the amount of debt contracted in the revolutionary war, and which, instead of redeeming our liberty, has been expended on sumptuous houses, carriages, and dinners. A fearful tax! if equalized on all; but overwhelming and convulsive by its partial fall. The crush will be tremendous; very different from that brought on by our paper money. That rose and fell so gradually that it kept all on their guard, and affected severely only early or long-winded contracts. Here the contract of yesterday crushes in an instant the one or the other party. The banks stopping payment suddenly, all their mercantile and city debtors do the same; and all, in short, except those in the country, who, possessing property, will be good in the end. But this resource will not enable them to pay a cent on the dollar. From the establishment of the United States Bank, to this day, I have preached against this system, but have been sensible no cure could be hoped but in the catastrophe now happening. The remedy was to let banks drop gradation at the expiration of their charters, and for the State governments to relinquish the power of establishing others. This would not, as it should not, have given the power of establishing them to Congress. But Congress could then have issued treasury notes payable within a fixed period, and founded on a specific tax, the proceeds of which, as they came in, should be exchangeable for the notes of that particular emission only. This depended, it is true, on the will of the State legislatures, and would have brought on us the phalanx of paper interest. But that interest is now defunct. Their gossamer castles are dissolved, and they can no longer impede and overawe the salutary measures of the government. Their paper was received on a belief that it was cash on demand. Themselves have declared it was nothing, and such scenes are now to take place as will open the eyes of credulity and of insanity itself, to the dangers of a paper medium abandoned to the discretion of avarice and of swindlers. It is impossible not to deplore our past follies, and their present consequences, but let them at least be warnings against like follies in future. The banks have discontinued themselves. We are now without any medium; and necessity, as well as patriotism and confidence, will make us all eager to receive treasury notes, if founded on specific taxes. Congress may now borrow of the public, and without interest, all the money they may want, to the amount of a competent circulation, by merely issuing their own promissory notes, of proper denominations for the larger purposes of circulation, but not for the small. Leave that door open for the entrance of metallic money. And, to give readier credit to their bills, without obliging themselves to give cash for them on demand, let their collectors be instructed to do so, when they have cash; thus, in some measure, performing the functions of a bank, as to their own notes. Providence seems, indeed, by a special dispensation, to have put down for us, without a struggle, that very paper enemy which the interest of our citizens long since required ourselves to put down, at whatever risk. The work is done. The moment is pregnant with futurity, and if not seized at once by Congress, I know not on what shoal our bark is next to be stranded. The State legislatures should be immediately urged to relinquish the right of establishing banks of discount. Most of them will comply, on patriotic principles, under the convictions of the moment; and the non-complying may be crowded into concurrence by legitimate devices. Vale, et me, ut amaris, ama.

TO SAMUEL H. SMITH, ESQ

Monticello, September 21, 1814.Dear Sir,—I learn from the newspapers that the Vandalism of our enemy has triumphed at Washington over science as well as the arts, by the destruction of the public library with the noble edifice in which it was deposited. Of this transaction, as of that of Copenhagen, the world will entertain but one sentiment. They will see a nation suddenly withdrawn from a great war, full armed and full handed, taking advantage of another whom they had recently forced into it, unarmed, and unprepared, to indulge themselves in acts of barbarism which do not belong to a civilized age. When Van Ghent destroyed their shipping at Chatham, and De Ruyter rode triumphantly up the Thames, he might in like manner, by the acknowledgment of their own historians, have forced all their ships up to London bridge, and there have burnt them, the tower, and city, had these examples been then set. London, when thus menaced, was near a thousand years old, Washington is but in its teens.

I presume it will be among the early objects of Congress to re-commence their collection. This will be difficult while the war continues, and intercourse with Europe is attended with so much risk. You know my collection, its condition and extent. I have been fifty years making it, and have spared no pains, opportunity or expense, to make it what it is. While residing in Paris, I devoted every afternoon I was disengaged, for a summer or two, in examining all the principal bookstores, turning over every book with my own hand, and putting by everything which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare and valuable in every science. Besides this, I had standing orders during the whole time I was in Europe, on its principal book-marts, particularly Amsterdam, Frankfort, Madrid and London, for such works relating to America as could not be found in Paris. So that in that department particularly, such a collection was made as probably can never again be effected, because it is hardly probable that the same opportunities, the same time, industry, perseverance and expense, with some knowledge of the bibliography of the subject, would again happen to be in concurrence. During the same period, and after my return to America, I was led to procure, also, whatever related to the duties of those in the high concerns of the nation. So that the collection, which I suppose is of between nine and ten thousand volumes, while it includes what is chiefly valuable in science and literature generally, extends more particularly to whatever belongs to the American statesman. In the diplomatic and parliamentary branches, it is particularly full. It is long since I have been sensible it ought not to continue private property, and had provided that at my death, Congress should have the refusal of it at their own price. But the loss they have now incurred, makes the present the proper moment for their accommodation, without regard to the small remnant of time and the barren use of my enjoying it. I ask of your friendship, therefore, to make for me the tender of it to the library committee of Congress, not knowing myself of whom the committee consists. I enclose you the catalogue, which will enable them to judge of its contents. Nearly the whole are well bound, abundance of them elegantly, and of the choicest editions existing. They may be valued by persons named by themselves, and the payment made convenient to the public. It may be, for instance, in such annual instalments as the law of Congress has left at their disposal, or in stock of any of their late loans, or of any loan they may institute at this session, so as to spare the present calls of our country, and await its days of peace and prosperity. They may enter, nevertheless, into immediate use of it, as eighteen or twenty wagons would place it in Washington in a single trip of a fortnight. I should be willing indeed, to retain a few of the books, to amuse the time I have yet to pass, which might be valued with the rest, but not included in the sum of valuation until they should be restored at my death, which I would carefully provide for, so that the whole library as it stands in the catalogue at this moment should be theirs without any garbling. Those I should like to retain would be chiefly classical and mathematical. Some few in other branches, and particularly one of the five encyclopedias in the catalogue. But this, if not acceptable, would not be urged. I must add, that I have not revised the library since I came home to live, so that it is probable some of the books may be missing, except in the chapters of Law and Divinity, which have been revised and stand exactly as in the catalogue. The return of the catalogue will of course be needed, whether the tender be accepted or not. I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a member of Congress may not have occasion to refer. But such a wish would not correspond with my views of preventing its dismemberment. My desire is either to place it in their hands entire, or to preserve it so here. I am engaged in making an alphabetical index of the author's names, to be annexed to the catalogue, which I will forward to you as soon as completed. Any agreement you shall be so good as to take the trouble of entering into with the committee, I hereby confirm. Accept the assurance of my great esteem and respect.

TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

Monticello, September 24, 1814.Dear Sir,—It is very long since I troubled you with a letter, which has proceeded from discretion and not want of inclination, because I have really had nothing to write which ought to have occupied your time. But in the late events at Washington I have felt so much for you that I cannot withhold the expression of my sympathies. For although every reasonable man must be sensible that all you can do is to order that execution must depend on others, and failures be imputed to them alone, yet I know that when such failures happen, they afflict even those who have done everything they could to prevent them. Had General Washington himself been now at the head of our affairs, the same event would probably have happened. We all remember the disgraces which befell us in his time in a trifling war with one or two petty tribes of Indians, in which two armies were cut off by not half their numbers. Every one knew, and I personally knew, because I was then of his council, that no blame was imputable to him, and that his officers alone were the cause of the disasters. They must now do the same justice. I am happy to turn to a countervailing event, and to congratulate you on the destruction of a second hostile fleet on the lakes by McDonough; of which, however, we have not the details. While our enemies cannot but feel shame for their barbarous achievements at Washington, they will be stung to the soul by these repeated victories over them on that element on which they wish the world to think them invincible. We have dissipated that error. They must now feel a conviction themselves that we can beat them gun to gun, ship to ship and fleet to fleet, and that their early successes on the land have been either purchased from traitors, or obtained from raw men entrusted of necessity with commands for which no experience had qualified them, and that every day is adding that experience to unquestioned bravery.

I am afraid the failure of our banks will occasion embarrassment for awhile, although it restores to us a fund which ought never to have been surrendered by the nation, and which now, prudently used, will carry us through all the fiscal difficulties of the war. At the request of Mr. Eppes, who was chairman of the committee of finance at the preceding session, I had written him some long letters on this subject. Colonel Monroe asked the reading of them some time ago, and I now send him another, written to a member of our legislature, who requested my ideas on the recent bank events. They are too long for your reading, but Colonel Monroe can, in a few sentences, state to you their outline.

Learning by the papers the loss of the library of Congress, I have sent my catalogue to S. H. Smith, to make to their library committee the offer of my collection, now of about nine or ten thousand volumes, which may be delivered to them instantly, on a valuation by persons of their own naming, and be paid for in any way, and at any term they please; in stock, for example, of any loan they have unissued, or of any one they may institute at this session; or in such annual instalments as are at the disposal of the committee. I believe you are acquainted with the condition of the books, should they wish to be ascertained of this. I have long been sensible that my library would be an interesting possession for the public, and the loss Congress has recently sustained, and the difficulty of replacing it, while our intercourse with Europe is so obstructed, renders this the proper moment for placing it at their service. Accept assurances of my constant and affectionate friendship and respect.