полная версия

полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 6 (of 9)

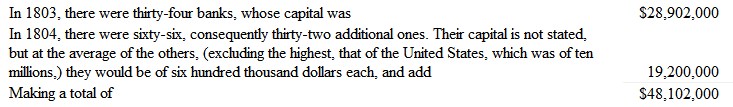

I have called the actual circulation of bank paper in the United States, two hundred millions of dollars. I do not recollect where I have seen this estimate; but I retain the impression that I thought it just at the time. It may be tested, however, by a list of the banks now in the United States, and the amount of their capital. I have no means of recurring to such a list for the present day; but I turn to two lists in my possession for the years of 1803 and 1804.

or say of fifty millions in round numbers. Now, every one knows the immense multiplication of these institutions since 1804. If they have only doubled, their capital will be of one hundred millions, and if trebled, as I think probable, it will be one hundred and fifty millions, on which they are at liberty to circulate treble the amount. I should sooner, therefore, believe two hundred millions to be far below than above the actual circulation. In England, by a late parliamentary document, (see Virginia Argus of October the 18th, 1813, and other public papers of about that date,) it appears that six years ago the Bank of England had twelve millions of pounds sterling in circulation, which had increased to forty-two millions in 1812, or to one hundred and eighty-nine millions of dollars. What proportion all the other banks may add to this, I do not know; if we were allowed to suppose they equal it, this would give a circulation of three hundred and seventy-eight millions, or the double of ours on a double population. But that nation is essentially commercial, ours essentially agricultural, and needing, therefore, less circulating medium, because the produce of the husbandman comes but once a year, and is then partly consumed at home, partly exchanged by barter. The dollar, which was of four shilling and sixpence sterling, was, by the same document, stated to be then six shillings and nine pence, a depreciation of exactly fifty per cent. The average price of wheat on the continent of Europe, at the commencement of its present war with England, was about a French crown, of one hundred and ten cents, the bushel. With us it was one hundred cents, and consequently we could send it there in competition with their own. That ordinary price has now doubled with us, and more than doubled in England; and although a part of this augmentation may proceed from the war demand, yet from the extraordinary nominal rise in the prices of land and labor here, both of which have nearly doubled in that period, and are still rising with every new bank, it is evident that were a general peace to take place to-morrow, and time allowed for the re-establishment of commerce, justice, and order, we could not afford to raise wheat for much less than two dollars, while the continent of Europe, having no paper circulation, and that of its specie not being augmented, would raise it at their former price of one hundred and ten cents. It follows, then, that with our redundancy of paper, we cannot, after peace, send a bushel of wheat to Europe, unless extraordinary circumstances double its price in particular places, and that then the exporting countries of Europe could undersell us.

It is said that our paper is as good as silver, because we may have silver for it at the bank where it issues. This is not true. One, two, or three persons might have it; but a general application would soon exhaust their vaults, and leave a ruinous proportion of their paper in its intrinsic worthless form. It is a fallacious pretence, for another reason. The inhabitants of the banking cities might obtain cash for their paper, as far as the cash of the vaults would hold out, but distance puts it out of the power of the country to do this. A farmer having a note of a Boston or Charleston bank, distant hundreds of miles, has no means of calling for the cash. And while these calls are impracticable for the country, the banks have no fear of their being made from the towns; because their inhabitants are mostly on their books, and there on sufferance only, and during good behavior.

In this state of things, we are called on to add ninety millions more to the circulation. Proceeding in this career, it is infallible, that we must end where the revolutionary paper ended. Two hundred millions was the whole amount of all the emissions of the old Congress, at which point their bills ceased to circulate. We are now at that sum, but with treble the population, and of course a longer tether. Our depreciation is, as yet, but about two for one. Owing to the support its credit receives from the small reservoirs of specie in the vaults of the banks, it is impossible to say at what point their notes will stop. Nothing is necessary to effect it but a general alarm; and that may take place whenever the public shall begin to reflect on, and perceive the impossibility that the banks should repay this sum. At present, caution is inspired no farther than to keep prudent men from selling property on long payments. Let us suppose the panic to arise at three hundred millions, a point to which every session of the legislatures hasten us by long strides. Nobody dreams that they would have three hundred millions of specie to satisfy the holders of their notes. Were they even to stop now, no one supposes they have two hundred millions in cash, or even the sixty-six and two-third millions, to which amount alone the law compels them to repay. One hundred and thirty-three and one-third millions of loss, then, is thrown on the public by law; and as to the sixty-six and two-thirds, which they are legally bound to pay, and ought to have in their vaults, every one knows there is no such amount of cash in the United States, and what would be the course with what they really have there? Their notes are refused. Cash is called for. The inhabitants of the banking towns will get what is in the vaults, until a few banks declare their insolvency; when, the general crush becoming evident, the others will withdraw even the cash they have, declare their bankruptcy at once, and leave an empty house and empty coffers for the holders of their notes. In this scramble of creditors, the country gets nothing, the towns but little. What are they to do? Bring suits? A million of creditors bring a million of suits against John Nokes and Robert Styles, wheresoever to be found? All nonsense. The loss is total. And a sum is thus swindled from our citizens, of seven times the amount of the real debt, and four times that of the fictitious one of the United States, at the close of the war. All this they will justly charge on their legislatures; but this will be poor satisfaction for the two or three hundred millions they will have lost. It is time, then, for the public functionaries to look to this. Perhaps it may not be too late. Perhaps, by giving time to the banks, they may call in and pay off their paper by degrees. But no remedy is ever to be expected while it rests with the State legislatures. Personal motive can be excited through so many avenues to their will, that, in their hands, it will continue to go on from bad to worse, until the catastrophe overwhelms us. I still believe, however, that on proper representations of the subject, a great proportion of these legislatures would cede to Congress their power of establishing banks, saving the charter rights already granted. And this should be asked, not by way of amendment to the constitution, because until three-fourths should consent, nothing could be done; but accepted from them one by one, singly, as their consent might be obtained. Any single State, even if no other should come into the measure, would find its interest in arresting foreign bank paper immediately, and its own by degrees. Specie would flow in on them as paper disappeared. Their own banks would call in and pay off their notes gradually, and their constituents would thus be saved from the general wreck. Should the greater part of the States concede, as is expected, their power over banks to Congress, besides insuring their own safety, the paper of the non-conceding States might be so checked and circumscribed, by prohibiting its receipt in any of the conceding States, and even in the non-conceding as to duties, taxes, judgments, or other demands of the United States, or of the citizens of other States, that it would soon die of itself, and the medium of gold and silver be universally restored. This is what ought to be done. But it will not be done. Carthago non delibitur. The overbearing clamor of merchants, speculators, and projectors, will drive us before them with our eyes open, until, as in France, under the Mississippi bubble, our citizens will be overtaken by the crush of this baseless fabric, without other satisfaction than that of execrations on the heads of those functionaries, who, from ignorance, pusillanimity or corruption, have betrayed the fruits of their industry into the hands of projectors and swindlers.

When I speak comparatively of the paper emission of the old Congress and the present banks, let it not be imagined that I cover them under the same mantle. The object of the former was a holy one; for if ever there was a holy war, it was that which saved our liberties and gave us independence. The object of the latter, is to enrich swindlers at the expense of the honest and industrious part of the nation.

The sum of what has been said is, that pretermitting the constitutional question on the authority of Congress, and considering this application on the grounds of reason alone, it would be best that our medium should be so proportioned to our produce, as to be on a par with that of the countries with which we trade, and whose medium is in a sound state; that specie is the most perfect medium, because it will preserve its own level; because, having intrinsic and universal value, it can never die in our hands, and it is the surest resource of reliance in time of war; that the trifling economy of paper, as a cheaper medium, or its convenience for transmission, weighs nothing in opposition to the advantages of the precious metals; that it is liable to be abused, has been, is, and forever will be abused, in every country in which it is permitted; that it is already at a term of abuse in these States, which has never been reached by any other nation, France excepted, whose dreadful catastrophe should be a warning against the instrument which produced it; that we are already at ten or twenty times the due quantity of medium; insomuch, that no man knows what his property is now worth, because it is bloating while he is calculating; and still less what it will be worth when the medium shall be relieved from its present dropsical state; and that it is a palpable falsehood to say we can have specie for our paper whenever demanded. Instead, then, of yielding to the cries of scarcity of medium set up by speculators, projectors and commercial gamblers, no endeavors should be spared to begin the work of reducing it by such gradual means as may give time to private fortunes to preserve their poise, and settle down with the subsiding medium; and that, for this purpose, the States should be urged to concede to the General Government, with a saving of chartered rights, the exclusive power of establishing banks of discount for paper.

To the existence of banks of discount for cash, as on the continent of Europe, there can be no objection, because there can be no danger of abuse, and they are a convenience both to merchants and individuals. I think they should even be encouraged, by allowing them a larger than legal interest on short discounts, and tapering thence, in proportion as the term of discount is lengthened, down to legal interest on those of a year or more. Even banks of deposit, where cash should be lodged, and a paper acknowledgment taken out as its representative, entitled to a return of the cash on demand, would be convenient for remittances, travelling persons, &c. But, liable as its cash would be to be pilfered and robbed, and its paper to be fraudulently re-issued, or issued without deposit, it would require skilful and strict regulation. This would differ from the bank of Amsterdam, in the circumstance that the cash could be redeemed on returning the note.

When I commenced this letter to you, my dear Sir, on Mr. Law's memorial, I expected a short one would have answered that. But as I advanced, the subject branched itself before me into so many collateral questions, that even the rapid views I have taken of each have swelled the volume of my letter beyond my expectations, and, I fear, beyond your patience. Yet on a revisal of it, I find no part which has not so much bearing on the subject as to be worth merely the time of perusal. I leave it then as it is; and will add only the assurances of my constant and affectionate esteem and respect.

TO JOHN JACOB ASTOR, ESQ

Monticello, November 9, 1813.Dear Sir,—Your favor of October 18th has been duly received, and I learn with great pleasure the progress you have made towards an establishment on Columbia river. I view it as the germ of a great, free and independent empire on that side of our continent, and that liberty and self-government spreading from that as well as this side, will ensure their complete establishment over the whole. It must be still more gratifying to yourself to foresee that your name will be handed down with that of Columbus and Raleigh, as the father of the establishment and founder of such an empire. It would be an afflicting thing indeed, should the English be able to break up the settlement. Their bigotry to the bastard liberty of their own country, and habitual hostility to every degree of freedom in any other, will induce the attempt; they would not lose the sale of a bale of furs for the freedom of the whole world. But I hope your party will be able to maintain themselves. If they have assiduously cultivated the interests and affections of the natives, these will enable them to defend themselves against the English, and furnish them an asylum even if their fort be lost. I hope, and have no doubt our government will do for its success whatever they have power to do, and especially that at the negotiations for peace, they will provide, by convention with the English, for the safety and independence of that country, and an acknowledgment of our right of patronizing them in all cases of injury from foreign nations. But no patronage or protection from this quarter can secure the settlement if it does not cherish the affections of the natives and make it their interest to uphold it. While you are doing so much for future generations of men, I sincerely wish you may find a present account in the just profits you are entitled to expect from the enterprise. I will ask of the President permission to read Mr. Stuart's journal. With fervent wishes for a happy issue to this great undertaking, which promises to form a remarkable epoch in the history of mankind, I tender you the assurance of my great esteem and respect.

JOHN ADAMS TO THOMAS JEFFERSON

Quincy, November 12, 1813.Dear Sir,—As I owe you more for your letters of October 12th and 28th than I shall be able to pay, I shall begin with the P. S. to the last.

I am very sorry to say that I cannot assist your memory in the inquiries of your letter of August 22d. I really know not who was the compositor of any one of the petitions or addresses you enumerate. Nay, further: I am certain I never did know. I was so shallow a politician that I was not aware of the importance of those compositions. They all appeared to me, in the circumstances of the country, like children's play at marbles or push-pin, or like misses in their teens, emulating each other in their pearls, their bracelets, their diamond pins and Brussels lace.

In the Congress of 1774, there was not one member, except Patrick Henry, who appeared to me sensible of the precipice, or rather the pinnacle on which we stood, and had candor and courage enough to acknowledge it. America is in total ignorance, or under infinite deception concerning that assembly. To draw the characters of them all would require a volume, and would now be considered as a characatured print. One-third Tories, another Whigs, and the rest Mongrels.

There was a little aristocracy among us of talents and letters. Mr. Dickinson was primus interpares, the bell-weather, the leader of the aristocratical flock.

Billy, alias Governor Livingston, and his son-in-law, Mr. Jay, were of the privileged order. The credit of most if not all those compositions, was often if not generally given to one or the other of these choice spirits. Mr. Dickinson, however, was not on any of the original committees. He came not into Congress till October 17th. He was not appointed till the 15th by his assembly.

Vol. 1, 30. Congress adjourned October 27th, though our correct secretary has not recorded any final adjournment or dissolution. Mr. Dickinson was in Congress but ten days. The business was all prepared, arranged, and even in a manner finished before his arrival.

R. H. Lee was the chairman of the committee for preparing the loyal and dutiful address to his majesty. Johnson and Henry were acute spirits, and understood the controversy very well, though they had not the advantages of education like Lee and John Rutledge.

The subject had been near a month under discussion in Congress, and most of the materials thrown out there. It underwent another deliberation in committee, after which they made the customary compliment to their chairman, by requesting him to prepare and report a draught, which was done, and after examination, correction, amelioration or pejoration, as usual reported to Congress. October 3d, 4th and 5th were taken up in debating and deliberating on matters proper to be contained in the address to his majesty, vol. 122. October 21st. The address to the king was, after debate, re-committed, and Mr. John Dickinson added to the committee. The first draught was made, and all the essential materials put together by Lee. It might be embellished and seasoned afterwards with some of Mr. Dickinson's piety, but I know not that it was. Neat and handsome as the composition is, having never had any confidence in the utility of it, I never have thought much about it since it was adopted. Indeed, I never bestowed much attention on any of those addresses which were all but repetitions of the same things, the same facts and arguments, dress and ornament rather than body, soul or substance. My thoughts and cares were nearly monopolized by the theory of our rights and wrongs, by measures for the defence of the country, and the means of governing ourselves. I was in a great error, no doubt, and am ashamed to confess it; for those things were necessary to give popularity to our cause both at home and abroad. And to show my stupidity in a stronger light, the reputation of any one of those compositions has been a more splendid distinction than any aristocratical star or garter in the escutcheon of every man who has enjoyed it. Very sorry that I cannot give you more satisfactory information, and more so that I cannot at present give more attention to your two last excellent letters. I am, as usual, affectionately yours.

N. B. I am almost ready to believe that John Taylor, of Caroline, or of Hazlewood, Port Royal, Virginia, is the author of 630 pages of printed octavo upon my books that I have received. The style answers every characteristic that you have intimated. Within a week I have received and looked into his Arator. They must spring from the same brain, as Minerva issued from the head of Jove, or rather as Venus rose from the froth of the sea. There is, however, a great deal of good sense in Arator, and there is some in his Aristocracy.

JOHN ADAMS TO THOMAS JEFFERSON

Quincy, November 15, 1813.Dear Sir,—Accept my thanks for the comprehensive syllabus in your favor of October 12th.

The Psalms of David, in sublimity, beauty, pathos and originality, or, in one word, in poetry, are superior to all the odes, hymns and songs in our language. But I had rather read them in our prose translation, than in any version I have seen. His morality, however, often shocks me, like Tristram Shandy's execrations.

Blacklock's translation of Horace's "Justum," is admirable; superior to Addison's. Could David be translated as well, his superiority would be universally acknowledged. We cannot compare the sublime poetry. By Virgil's "Pollio," we may conjecture there was prophecy as well as sublimity. Why have those verses been annihilated? I suspect Platonic Christianity, Pharisaical Judaism or Machiavilian politics, in this case, as in all other cases, of the destruction of records and literary monuments,

The auri sacra fames, et dominandi sæva cupido.Among all your researches in Hebrew history and controversy, have you ever met a book the design of which is to prove that the ten commandments, as we have them in our Catechisms and hung up in our churches, were not the ten commandments written by the finger of God upon tables delivered to Moses on Mount Sinai, and broken by him in a passion with Aaron for his golden calf, nor those afterwards engraved by him on tables of stone; but a very different set of commandments?

There is such a book, by J. W. Goethen, Schriften, Berlin 1775-1779. I wish to see this book. You will perceive the question in Exodus, 20: 1, 17, 22, 28, chapter 24: 3, &c.; chapter 24: 12; chapter 25: 31; chapter 31: 18; chapter 31: 19; chapter 34: 1; chapter 34: 10, &c.

I will make a covenant with all this people. Observe that which I command this day:

1. Thou shalt not adore any other God. Therefore take heed not to enter into covenant with the inhabitants of the country; neither take for your sons their daughters in marriage. They would allure thee to the worship of false Gods. Much less shall you in any place erect images.

2. The feast of unleavened bread shalt thou keep. Seven days shalt thou eat unleavened bread, at the time of the month Abib; to remember that about that time, I delivered thee from Egypt.

3. Every first born of the mother is mine; the male of thine herd, be it stock or flock. But you shall replace the first born of an ass with a sheep. The first born of your sons shall you redeem. No man shall appear before me with empty hands.

4. Six days shalt thou labor. The seventh day thou shalt rest from ploughing and gathering.

5. The feast of weeks shalt thou keep with the firstlings of the wheat harvest; and the feast of harvesting at the end of the year.

6. Thrice in every year all male persons shall appear before the Lord. Nobody shall invade your country, as long as you obey this command.

7. Thou shalt not sacrifice the blood of a sacrifice of mine, upon leavened bread.

8. The sacrifice of the Passover shall not remain till the next day.

9. The firstlings of the produce of your land, thou shalt bring to the house of the Lord.

10. Thou shalt not boil the kid, while it is yet sucking.

And the Lord spake to Moses: Write these words, as after these words I made with you and with Israel a covenant.

I know not whether Goethen translated or abridged from the Hebrew, or whether he used any translation, Greek, Latin, or German. But he differs in form and words somewhat from our version, Exodus 34: 10 to 28. The sense seems to be the same. The tables were the evidence of the covenant, by which the Almighty attached the people of Israel to himself. By these laws they were separated from all other nations, and were reminded of the principal epochs of their history.

When and where originated our ten commandments? The tables and the ark were lost. Authentic copies in few, if any hands; the ten Precepts could not be observed, and were little remembered.

If the book of Deuteronomy was compiled, during or after the Babylonian captivity, from traditions, the error or amendment might come in those.

But you must be weary, as I am at present of problems, conjectures, and paradoxes, concerning Hebrew, Grecian and Christian and all other antiquities; but while we believe that the finis bonorum will be happy, we may leave learned men to their disquisitions and criticisms.

I admire your employment in selecting the philosophy and divinity of Jesus, and separating it from all mixtures. If I had eyes and nerves I would go through both Testaments and mark all that I understand. To examine the Mishna, Gemara, Cabbala, Jezirah, Sohar, Cosri and Talmud of the Hebrews would require the life of Methuselah, and after all his 969 years would be wasted to very little purpose. The dæmon of hierarchical despotism has been at work both with the Mishna and Gemara. In 1238 a French Jew made a discovery to the Pope (Gregory 9th) of the heresies of the Talmud. The Pope sent thirty-five articles of error to the Archbishops of France, requiring them to seize the books of the Jews and burn all that contained any errors. He wrote in the same terms to the kings of France, England, Arragon, Castile, Leon, Navarre and Portugal. In consequence of this order, twenty cartloads of Hebrew books were burnt in France; and how many times twenty cartloads were destroyed in the other kingdoms? The Talmud of Babylon and that of Jerusalem were composed from 120 to 500 years after the destruction of Jerusalem.