полная версия

полная версияThe Stones of Venice, Volume 2 (of 3)

[152] Inscribed, I believe, Pietas, meaning general reverence and godly fear.

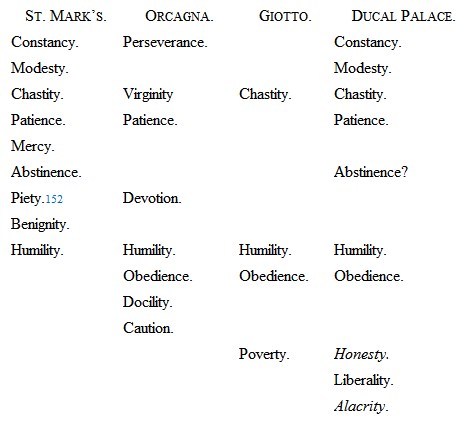

§ LXIV. It is curious, that in none of these lists do we find either Honesty or Industry ranked as a virtue, except in the Venetian one, where the latter is implied in Alacritas, and opposed not only by “Accidia” or sloth, but by a whole series of eight sculptures on another capital, illustrative, as I believe, of the temptations to idleness; while various other capitals, as we shall see presently, are devoted to the representation of the active trades. Industry, in Northern art and Northern morality, assumes a very principal place. I have seen in French manuscripts the virtues reduced to these seven, Charity, Chastity, Patience, Abstinence, Humility, Liberality, and Industry: and I doubt whether, if we were but to add Honesty (or Truth), a wiser or shorter list could be made out.

§ LXV. We will now take the pillars of the Ducal Palace in their order. It has already been mentioned (Vol. I. Chap. I. § XLVI.) that there are, in all, thirty-six great pillars supporting the lower story; and that these are to be counted from right to left, because then the more ancient of them come first: and that, thus arranged, the first, which is not a shaft, but a pilaster, will be the support of the Vine angle; the eighteenth will be the great shaft of the Fig-tree angle; and the thirty-sixth, that of the Judgment angle.

§ LXVI. All their capitals, except that of the first, are octagonal, and are decorated by sixteen leaves, differently enriched in every capital, but arranged in the same way; eight of them rising to the angles, and there forming volutes; the eight others set between them, on the sides, rising half-way up the bell of the capital; there nodding forward, and showing above them, rising out of their luxuriance, the groups or single figures which we have to examine.149 In some instances, the intermediate or lower leaves are reduced to eight sprays of foliage; and the capital is left dependent for its effect on the bold position of the figures. In referring to the figures on the octagonal capitals, I shall call the outer side, fronting either the Sea or the Piazzetta, the first side; and so count round from left to right; the fourth side being thus, of course, the innermost. As, however, the first five arches were walled up after the great fire, only three sides of their capitals are left visible, which we may describe as the front and the eastern and western sides of each.

§ LXVII. First Capital: i.e. of the pilaster at the Vine angle.

In front, towards the Sea. A child holding a bird before him, with its wings expanded, covering his breast.

On its eastern side. Children’s heads among leaves.

On its western side. A child carrying in one hand a comb; in the other, a pair of scissors.

It appears curious, that this, the principal pilaster of the façade, should have been decorated only by these graceful grotesques, for I can hardly suppose them anything more. There may be meaning in them, but I will not venture to conjecture any, except the very plain and practical meaning conveyed by the last figure to all Venetian children, which it would be well if they would act upon. For the rest, I have seen the comb introduced in grotesque work as early as the thirteenth century, but generally for the purpose of ridiculing too great care in dressing the hair, which assuredly is not its purpose here. The children’s heads are very sweet and full of life, but the eyes sharp and small.

§ LXVIII. Second Capital. Only three sides of the original work are left unburied by the mass of added wall. Each side has a bird, one web-footed, with a fish, one clawed, with a serpent, which opens its jaws, and darts its tongue at the bird’s breast; the third pluming itself, with a feather between the mandibles of its bill. It is by far the most beautiful of the three capitals decorated with birds.

Third Capital. Also has three sides only left. They have three heads, large, and very ill cut; one female, and crowned.

Fourth Capital. Has three children. The eastern one is defaced: the one in front holds a small bird, whose plumage is beautifully indicated, in its right hand; and with its left holds up half a walnut, showing the nut inside: the third holds a fresh fig, cut through, showing the seeds.

The hair of all the three children is differently worked: the first has luxuriant flowing hair, and a double chin; the second, light flowing hair falling in pointed locks on the forehead; the third, crisp curling hair, deep cut with drill holes.

This capital has been copied on the Renaissance side of the palace, only with such changes in the ideal of the children as the workman thought expedient and natural. It is highly interesting to compare the child of the fourteenth with the child of the fifteenth century. The early heads are full of youthful life, playful, humane, affectionate, beaming with sensation and vivacity, but with much manliness and firmness, also, not a little cunning, and some cruelty perhaps, beneath all; the features small and hard, and the eyes keen. There is the making of rough and great men in them. But the children of the fifteenth century are dull smooth-faced dunces, without a single meaning line in the fatness of their stolid cheeks; and, although, in the vulgar sense, as handsome as the other children are ugly, capable of becoming nothing but perfumed coxcombs.

Fifth Capital. Still three sides only left, bearing three half-length statues of kings; this is the first capital which bears any inscription. In front, a king with a sword in his right hand points to a handkerchief embroidered and fringed, with a head on it, carved on the cavetto of the abacus. His name is written above, “TITUS VESPASIAN IMPERATOR” (contracted

On eastern side, “TRAJANUS IMPERATOR.” Crowned, a sword in right hand, and sceptre in left.

On western, “(OCT)AVIANUS AUGUSTUS IMPERATOR.” The “OCT” is broken away. He bears a globe in his right hand, with “MUNDUS PACIS” upon it; a sceptre in his left, which I think has terminated in a human figure. He has a flowing beard, and a singularly high crown; the face is much injured, but has once been very noble in expression.

Sixth Capital. Has large male and female heads, very coarsely cut, hard, and bad.

§ LXIX. Seventh Capital. This is the first of the series which is complete; the first open arch of the lower arcade being between it and the sixth. It begins the representation of the Virtues.

First side. Largitas, or Liberality: always distinguished from the higher Charity. A male figure, with his lap full of money, which he pours out of his hand. The coins are plain, circular, and smooth; there is no attempt to mark device upon them. The inscription above is, “LARGITAS ME ONORAT.”

In the copy of this design on the twenty-fifth capital, instead of showering out the gold from his open hand, the figure holds it in a plate or salver, introduced for the sake of disguising the direct imitation. The changes thus made in the Renaissance pillars are always injuries.

This virtue is the proper opponent of Avarice; though it does not occur in the systems of Orcagna or Giotto, being included in Charity. It was a leading virtue with Aristotle and the other ancients.

§ LXX. Second side. Constancy; not very characteristic. An armed man with a sword in his hand, inscribed, “CONSTANTIA SUM, NIL TIMENS.”

This virtue is one of the forms of fortitude, and Giotto therefore sets as the vice opponent to Fortitude, “Inconstantia,” represented as a woman in loose drapery, falling from a rolling globe. The vision seen in the interpreter’s house in the Pilgrim’s Progress, of the man with a very bold countenance, who says to him who has the writer’s ink-horn by his side, “Set down my name,” is the best personification of the Venetian “Constantia” of which I am aware in literature. It would be well for us all to consider whether we have yet given the order to the man with the ink-horn, “Set down my name.”

§ LXXI. Third side. Discord; holding up her finger, but needing the inscription above to assure us of her meaning, “DISCORDIA SUM, DISCORDANS.” In the Renaissance copy she is a meek and nun-like person with a veil.

She is the Atë of Spenser; “mother of debate,” thus described in the fourth book:

“Her face most fowle and filthy was to see,

With squinted eyes contrarie wayes intended;

And loathly mouth, unmeete a mouth to bee,

That nought but gall and venim comprehended,

And wicked wordes that God and man offended:

Her lying tongue was in two parts divided,

And both the parts did speake, and both contended;

And as her tongue, so was her hart discided,

That never thoght one thing, but doubly stil was guided.”

Note the fine old meaning of “discided,” cut in two; it is a great pity we have lost this powerful expression. We might keep “determined” for the other sense of the word.

§ LXXII. Fourth side. Patience. A female figure, very expressive and lovely, in a hood, with her right hand on her breast, the left extended, inscribed “PATIENTIA MANET MECUM.”

She is one of the principal virtues in all the Christian systems: a masculine virtue in Spenser, and beautifully placed as the Physician in the House of Holinesse. The opponent vice, Impatience, is one of the hags who attend the Captain of the Lusts of the Flesh; the other being Impotence. In like manner, in the “Pilgrim’s Progress,” the opposite of Patience is Passion; but Spenser’s thought is farther carried. His two hags, Impatience and Impotence, as attendant upon the evil spirit of Passion, embrace all the phenomena of human conduct, down even to the smallest matters, according to the adage, “More haste, worse speed.”

§ LXXIII. Fifth side. Despair. A female figure thrusting a dagger into her throat, and tearing her long hair, which flows down among the leaves of the capital below her knees. One of the finest figures of the series; inscribed “DESPERACIO MÔS (mortis?) CRUDELIS.” In the Renaissance copy she is totally devoid of expression, and appears, instead of tearing her hair, to be dividing it into long curls on each side.

This vice is the proper opposite of Hope. By Giotto she is represented as a woman hanging herself, a fiend coming for her soul. Spenser’s vision of Despair is well known, it being indeed currently reported that this part of the Faerie Queen was the first which drew to it the attention of Sir Philip Sidney.

§ LXXIV. Sixth side. Obedience: with her arms folded; meek, but rude and commonplace, looking at a little dog standing on its hind legs and begging, with a collar round its neck. Inscribed “OBEDIENTI * *;” the rest of the sentence is much defaced, but looks like

This virtue is, of course, a principal one in the monkish systems; represented by Giotto at Assisi as “an angel robed in black, placing the finger of his left hand on his mouth, and passing the yoke over the head of a Franciscan monk kneeling at his feet.”150

Obedience holds a less principal place in Spenser. We have seen her above associated with the other peculiar virtues of womanhood.

§ LXXV. Seventh side. Infidelity. A man in a turban, with a small image in his hand, or the image of a child. Of the inscription nothing but “INFIDELITATE * * *” and some fragmentary letters, “ILI, CERO,” remain.

By Giotto Infidelity is most nobly symbolized as a woman helmeted, the helmet having a broad rim which keeps the light from her eyes. She is covered with heavy drapery, stands infirmly as if about to fall, is bound by a cord round her neck to an image which she carries in her hand, and has flames bursting forth at her feet.

In Spenser, Infidelity is the Saracen knight Sans Foy,—

“Full large of limbe and every jointHe was, and cared not for God or man a point.”For the part which he sustains in the contest with Godly Fear, or the Red-cross knight, see Appendix 2, Vol. III.

§ LXXVI. Eighth side. Modesty; bearing a pitcher. (In the Renaissance copy, a vase like a coffee-pot.) Inscribed “MODESTIA

I do not find this virtue in any of the Italian series, except that of Venice. In Spenser she is of course one of those attendant on Womanhood, but occurs as one of the tenants of the Heart of Man, thus portrayed in the second book:

“Straunge was her tyre, and all her garment blew,Close rownd about her tuckt with many a plight:Upon her fist the bird which shonneth vew...........And ever and anone with rosy redThe bashfull blood her snowy cheekes did dye,That her became, as polisht yvoryWhich cunning craftesman hand hath overlaydWith fayre vermilion or pure castory.”§ LXXVII. Eighth Capital. It has no inscriptions, and its subjects are not, by themselves, intelligible; but they appear to be typical of the degradation of human instincts.

First side. A caricature of Arion on his dolphin; he wears a cap ending in a long proboscis-like horn, and plays a violin with a curious twitch of the bow and wag of the head, very graphically expressed, but still without anything approaching to the power of Northern grotesque. His dolphin has a goodly row of teeth, and the waves beat over his back.

Second side. A human figure, with curly hair and the legs of a bear; the paws laid, with great sculptural skill, upon the foliage. It plays a violin, shaped like a guitar, with a bent double-stringed bow.

Third side. A figure with a serpent’s tail and a monstrous head, founded on a Negro type, hollow-cheeked, large-lipped, and wearing a cap made of a serpent’s skin, holding a fir-cone in its hand.

Fourth side. A monstrous figure, terminating below in a tortoise. It is devouring a gourd, which it grasps greedily with both hands; it wears a cap ending in a hoofed leg.

Fifth side. A centaur wearing a crested helmet, and holding a curved sword.

Sixth side. A knight, riding a headless horse, and wearing chain armor, with a triangular shield flung behind his back, and a two-edged sword.

Seventh side. A figure like that on the fifth, wearing a round helmet, and with the legs and tail of a horse. He bears a long mace with a top like a fir-cone.

Eighth side. A figure with curly hair, and an acorn in its hand, ending below in a fish.

§ LXXVIII. Ninth Capital. First side. Faith. She has her left hand on her breast, and the cross on her right. Inscribed “FIDES OPTIMA IN DEO.” The Faith of Giotto holds the cross in her right hand; in her left, a scroll with the Apostles’ Creed. She treads upon cabalistic books, and has a key suspended to her waist. Spenser’s Faith (Fidelia) is still more spiritual and noble:

“She was araied all in lilly white,And in her right hand bore a cup of gold,With wine and water fild up to the hight,In which a serpent did himselfe enfold,That horrour made to all that did behold;But she no whitt did chaunge her constant mood:And in her other hand she fast did holdA booke, that was both signd and seald with blood;Wherein darke things were writt, hard to be understood.”§ LXXIX. Second side. Fortitude. A long-bearded man [Samson?] tearing open a lion’s jaw. The inscription is illegible, and the somewhat vulgar personification appears to belong rather to Courage than Fortitude. On the Renaissance copy it is inscribed “FORTITUDO SUM VIRILIS.” The Latin word has, perhaps, been received by the sculptor as merely signifying “Strength,” the rest of the perfect idea of this virtue having been given in “Constantia” previously. But both these Venetian symbols together do not at all approach the idea of Fortitude as given generally by Giotto and the Pisan sculptors; clothed with a lion’s skin, knotted about her neck, and falling to her feet in deep folds; drawing back her right hand, with the sword pointed towards her enemy; and slightly retired behind her immovable shield, which, with Giotto, is square, and rested on the ground like a tower, covering her up to above her shoulders; bearing on it a lion, and with broken heads of javelins deeply infixed.

Among the Greeks, this is, of course, one of the principal virtues; apt, however, in their ordinary conception of it to degenerate into mere manliness or courage.

§ LXXX. Third side. Temperance; bearing a pitcher of water and a cup. Inscription, illegible here, and on the Renaissance copy nearly so, “TEMPERANTIA SUM” (INOM’ Ls)? only left. In this somewhat vulgar and most frequent conception of this virtue (afterwards continually repeated, as by Sir Joshua in his window at New College) temperance is confused with mere abstinence, the opposite of Gula, or gluttony; whereas the Greek Temperance, a truly cardinal virtue, is the moderator of all the passions, and so represented by Giotto, who has placed a bridle upon her lips, and a sword in her hand, the hilt of which she is binding to the scabbard. In his system, she is opposed among the vices, not by Gula or Gluttony, but by Ira, Anger. So also the Temperance of Spenser, or Sir Guyon, but with mingling of much sternness:

“A goodly knight, all armd in harnesse meete,That from his head no place appeared to his feete,His carriage was full comely and upright;His countenance demure and temperate;But yett so sterne and terrible in sight,That cheard his friendes, and did his foes amate.”The Temperance of the Greeks, σωφροσύνη, involves the idea of Prudence, and is a most noble virtue, yet properly marked by Plato as inferior to sacred enthusiasm, though necessary for its government. He opposes it, under the name “Mortal Temperance” or “the Temperance which is of men,” to divine madness, μανία, or inspiration; but he most justly and nobly expresses the general idea of it under the term ὓβρις, which, in the “Phædrus,” is divided into various intemperances with respect to various objects, and set forth under the image of a black, vicious, diseased and furious horse, yoked by the side of Prudence or Wisdom (set forth under the figure of a white horse with a crested and noble head, like that which we have among the Elgin Marbles) to the chariot of the Soul. The system of Aristotle, as above stated, is throughout a mere complicated blunder, supported by sophistry, the laboriously developed mistake of Temperance for the essence of the virtues which it guides. Temperance in the mediæval systems is generally opposed by Anger, or by Folly, or Gluttony: but her proper opposite is Spenser’s Acrasia, the principal enemy of Sir Guyon, at whose gates we find the subordinate vice “Excesse,” as the introduction to Intemperance; a graceful and feminine image, necessary to illustrate the more dangerous forms of subtle intemperance, as opposed to the brutal “Gluttony” in the first book. She presses grapes into a cup, because of the words of St. Paul, “Be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess;” but always delicately,

“Into her cup she scruzd with daintie breachOf her fine fingers, without fowle empeach,That so faire winepresse made the wine more sweet.”The reader will, I trust, pardon these frequent extracts from Spenser, for it is nearly as necessary to point out the profound divinity and philosophy of our great English poet, as the beauty of the Ducal Palace.

§ LXXXI. Fourth side. Humility; with a veil upon her head, carrying a lamp in her lap. Inscribed in the copy, “HUMILITAS HABITAT IN ME.”

This virtue is of course a peculiarly Christian one, hardly recognized in the Pagan systems, though carefully impressed upon the Greeks in early life in a manner which at this day it would be well if we were to imitate, and, together with an almost feminine modesty, giving an exquisite grace to the conduct and bearing of the well-educated Greek youth. It is, of course, one of the leading virtues in all the monkish systems, but I have not any notes of the manner of its representation.

§ LXXXII. Fifth side. Charity. A woman with her lap full of loaves (?), giving one to a child, who stretches his arm out for it across a broad gap in the leafage of the capital.

Again very far inferior to the Giottesque rendering of this virtue. In the Arena Chapel she is distinguished from all the other virtues by having a circular glory round her head, and a cross of fire; she is crowned with flowers, presents with her right hand a vase of corn and fruit, and with her left receives treasure from Christ, who appears above her, to provide her with the means of continual offices of beneficence, while she tramples under foot the treasures of the earth.

The peculiar beauty of most of the Italian conceptions of Charity, is in the subjection of mere munificence to the glowing of her love, always represented by flames; here in the form of a cross round her head; in Oreagna’s shrine at Florence, issuing from a censer in her hand; and, with Dante, inflaming her whole form, so that, in a furnace of clear fire, she could not have been discerned.

Spenser represents her as a mother surrounded by happy children, an idea afterwards grievously hackneyed and vulgarized by English painters and sculptors.

§ LXXXIII. Sixth side. Justice. Crowned, and with sword. Inscribed in the copy, “REX SUM JUSTICIE.”

This idea was afterwards much amplified and adorned in the only good capital of the Renaissance series, under the Judgment angle. Giotto has also given his whole strength to the painting of this virtue, representing her as enthroned under a noble Gothic canopy, holding scales, not by the beam, but one in each hand; a beautiful idea, showing that the equality of the scales of Justice is not owing to natural laws, but to her own immediate weighing the opposed causes in her own hands. In one scale is an executioner beheading a criminal; in the other an angel crowning a man who seems (in Selvatico’s plate) to have been working at a desk or table.

Beneath her feet is a small predella, representing various persons riding securely in the woods, and others dancing to the sound of music.

Spenser’s Justice, Sir Artegall, is the hero of an entire book, and the betrothed knight of Britomart, or chastity.

§ LXXXIV. Seventh side. Prudence. A man with a book and a pair of compasses, wearing the noble cap, hanging down towards the shoulder, and bound in a fillet round the brow, which occurs so frequently during the fourteenth century in Italy in the portraits of men occupied in any civil capacity.

This virtue is, as we have seen, conceived under very different degrees of dignity, from mere worldly prudence up to heavenly wisdom, being opposed sometimes by Stultitia, sometimes by Ignorantia. I do not find, in any of the representations of her, that her truly distinctive character, namely, forethought, is enough insisted upon: Giotto expresses her vigilance and just measurement or estimate of all things by painting her as Janus-headed, and gazing into a convex mirror, with compasses in her right hand; the convex mirror showing her power of looking at many things in small compass. But forethought or anticipation, by which, independently of greater or less natural capacities, one man becomes more prudent than another, is never enough considered or symbolized.

The idea of this virtue oscillates, in the Greek systems, between Temperance and Heavenly Wisdom.

§ LXXXV. Eighth side. Hope. A figure full of devotional expression, holding up its hands as in prayer, and looking to a hand which is extended towards it out of sunbeams. In the Renaissance copy this hand does not appear.

Of all the virtues, this is the most distinctively Christian (it could not, of course, enter definitely into any Pagan scheme); and above all others, it seems to me the testing virtue,—that by the possession of which we may most certainly determine whether we are Christians or not; for many men have charity, that is to say, general kindness of heart, or even a kind of faith, who have not any habitual hope of, or longing for, heaven. The Hope of Giotto is represented as winged, rising in the air, while an angel holds a crown before her. I do not know if Spenser was the first to introduce our marine virtue, leaning on an anchor, a symbol as inaccurate as it is vulgar: for, in the first place, anchors are not for men, but for ships; and in the second, anchorage is the characteristic not of Hope, but of Faith. Faith is dependent, but Hope is aspirant. Spenser, however, introduces Hope twice,—the first time as the Virtue with the anchor; but afterwards fallacious Hope, far more beautifully, in the Masque of Cupid: