полная версия

полная версияThe Stones of Venice, Volume 2 (of 3)

§ XLVI. Now, exactly in proportion as the Christian religion became less vital, and as the various corruptions which time and Satan brought into it were able to manifest themselves, the person and offices of Christ were less dwelt upon, and the virtues of Christians more. The Life of the Believer became in some degree separated from the Life of Christ; and his virtue, instead of being a stream flowing forth from the throne of God, and descending upon the earth, began to be regarded by him as a pyramid upon earth, which he had to build up, step by step, that from the top of it he might reach the Heavens. It was not possible to measure the waves of the water of life, but it was perfectly possible to measure the bricks of the Tower of Babel; and gradually, as the thoughts of men were withdrawn from their Redeemer, and fixed upon themselves, the virtues began to be squared, and counted, and classified, and put into separate heaps of firsts and seconds; some things being virtuous cardinally, and other things virtuous only north-north-west. It is very curious to put in close juxtaposition the words of the Apostles and of some of the writers of the fifteenth century touching sanctification. For instance, hear first St. Paul to the Thessalonians: “The very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. Faithful is he that calleth you, who also will do it.” And then the following part of a prayer which I translate from a MS. of the fifteenth century: “May He (the Holy Spirit) govern the five Senses of my body; may He cause me to embrace the Seven Works of Mercy, and firmly to believe and observe the Twelve Articles of the Faith and the Ten Commandments of the Law, and defend me from the Seven Mortal Sins, even to the end.”

§ XLVII. I do not mean that this quaint passage is generally characteristic of the devotion of the fifteenth century: the very prayer out of which it is taken is in other parts exceedingly beautiful:139 but the passage is strikingly illustrative of the tendency of the later Romish Church, more especially in its most corrupt condition, just before the Reformation, to throw all religion into forms and ciphers; which tendency, as it affected Christian ethics, was confirmed by the Renaissance enthusiasm for the works of Aristotle and Cicero, from whom the code of the fifteenth century virtues was borrowed, and whose authority was then infinitely more revered by all the Doctors of the Church than that either of St. Paul or St. Peter.

§ XLVIII. Although, however, this change in the tone of the Christian mind was most distinctly manifested when the revival of literature rendered the works of the heathen philosophers the leading study of all the greatest scholars of the period, it had been, as I said before, taking place gradually from the earliest ages. It is, as far as I know, that root of the Renaissance poison-tree, which, of all others, is deepest struck; showing itself in various measures through the writings of all the Fathers, of course exactly in proportion to the respect which they paid to classical authors, especially to Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. The mode in which the pestilent study of that literature affected them may be well illustrated by the examination of a single passage from the works of one of the best of them, St. Ambrose, and of the mode in which that passage was then amplified and formulized by later writers.

§ XLIX. Plato, indeed, studied alone, would have done no one any harm. He is profoundly spiritual and capacious in all his views, and embraces the small systems of Aristotle and Cicero, as the solar system does the Earth. He seems to me especially remarkable for the sense of the great Christian virtue of Holiness, or sanctification; and for the sense of the presence of the Deity in all things, great or small, which always runs in a solemn undercurrent beneath his exquisite playfulness and irony; while all the merely moral virtues may be found in his writings defined in the most noble manner, as a great painter defines his figures, without outlines. But the imperfect scholarship of later ages seems to have gone to Plato, only to find in him the system of Cicero; which indeed was very definitely expressed by him. For it having been quickly felt by all men who strove, unhelped by Christian faith, to enter at the strait gate into the paths of virtue, that there were four characters of mind which were protective or preservative of all that was best in man, namely, Prudence, Justice, Courage, and Temperance,140 these were afterwards, with most illogical inaccuracy, called cardinal virtues, Prudence being evidently no virtue, but an intellectual gift: but this inaccuracy arose partly from the ambiguous sense of the Latin word “virtutes,” which sometimes, in mediæval language, signifies virtues, sometimes powers (being occasionally used in the Vulgate for the word “hosts,” as in Psalm ciii. 21, cxlviii. 2, &c., while “fortitudines” and “exercitus” are used for the same word in other places), so that Prudence might properly be styled a power, though not properly a virtue; and partly from the confusion of Prudence with Heavenly Wisdom. The real rank of these four virtues, if so they are to be called, is however properly expressed by the term “cardinal.” They are virtues of the compass, those by which all others are directed and strengthened; they are not the greatest virtues, but the restraining or modifying virtues, thus Prudence restrains zeal, Justice restrains mercy, Fortitude and Temperance guide the entire system of the passions; and, thus understood, these virtues properly assumed their peculiar leading or guiding position in the system of Christian ethics. But in Pagan ethics, they were not only guiding, but comprehensive. They meant a great deal more on the lips of the ancients, than they now express to the Christian mind. Cicero’s Justice includes charity, beneficence, and benignity, truth, and faith in the sense of trustworthiness. His Fortitude includes courage, self-command, the scorn of fortune and of all temporary felicities. His Temperance includes courtesy and modesty. So also, in Plato, these four virtues constitute the sum of education. I do not remember any more simple or perfect expression of the idea, than in the account given by Socrates, in the “Alcibiades I.,” of the education of the Persian kings, for whom, in their youth, there are chosen, he says, four tutors from among the Persian nobles; namely, the Wisest, the most Just, the most Temperate, and the most Brave of them. Then each has a distinct duty: “The Wisest teaches the young king the worship of the gods, and the duties of a king (something more here, observe, than our ‘Prudence!’); the most Just teaches him to speak all truth, and to act out all truth, through the whole course of his life; the most Temperate teaches him to allow no pleasure to have the mastery of him, so that he may be truly free, and indeed a king; and the most Brave makes him fearless of all things, showing him that the moment he fears anything, he becomes a slave.”

§ L. All this is exceedingly beautiful, so far as it reaches; but the Christian divines were grievously led astray by their endeavors to reconcile this system with the nobler law of love. At first, as in the passage I am just going to quote from St. Ambrose, they tried to graft the Christian system on the four branches of the Pagan one; but finding that the tree would not grow, they planted the Pagan and Christian branches side by side; adding, to the four cardinal virtues, the three called by the schoolmen theological, namely, Faith, Hope, and Charity: the one series considered as attainable by the Heathen, but the other by the Christian only. Thus Virgil to Sordello:

“Loco e laggiù, non tristo da martiriMa di tenebre solo, ove i lamentiNon suonan come guai, ma son sospiri:..........Quivi sto io, con quei che le tre santeVirtù non si vestiro, e senza vizioConobbei l’ altre, e seguir, tutte quante.”…“There I with those abideWho the Three Holy Virtues put not on,But understood the rest, and without blameFollowed them all.”Cary.§ LI. This arrangement of the virtues was, however, productive of infinite confusion and error: in the first place, because Faith is classed with its own fruits,—the gift of God, which is the root of the virtues, classed simply as one of them; in the second, because the words used by the ancients to express the several virtues had always a different meaning from the same expressions in the Bible, sometimes a more extended, sometimes a more limited one. Imagine, for instance, the confusion which must have been introduced into the ideas of a student who read St. Paul and Aristotle alternately; considering that the word which the Greek writer uses for Justice, means, with St. Paul, Righteousness. And lastly, it is impossible to overrate the mischief produced in former days, as well as in our own, by the mere habit of reading Aristotle, whose system is so false, so forced, and so confused, that the study of it at our universities is quite enough to occasion the utter want of accurate habits of thought which so often disgraces men otherwise well-educated. In a word, Aristotle mistakes the Prudence or Temperance which must regulate the operation of the virtues, for the essence of the virtues themselves; and, striving to show that all virtues are means between two opposite vices, torments his wit to discover and distinguish as many pairs of vices as are necessary to the completion of his system, not disdaining to employ sophistry where invention fails him.

And, indeed, the study of classical literature, in general, not only fostered in the Christian writers the unfortunate love of systematizing, which gradually degenerated into every species of contemptible formulism, but it accustomed them to work out their systems by the help of any logical quibble, or verbal subtlety, which could be made available for their purpose, and this not with any dishonest intention, but in a sincere desire to arrange their ideas in systematical groups, while yet their powers of thought were not accurate enough, nor their common sense stern enough, to detect the fallacy, or disdain the finesse, by which these arrangements were frequently accomplished.

§ LII. Thus St. Ambrose, in his commentary on Luke vi. 20, is resolved to transform the four Beatitudes there described into rewards of the four cardinal Virtues, and sets himself thus ingeniously to the task:

“‘Blessed be ye poor.’ Here you have Temperance. ‘Blessed are ye that hunger now.’ He who hungers, pities those who are an-hungered; in pitying, he gives to them, and in giving he becomes just (largiendo fit Justus). ‘Blessed are ye that weep now, for ye shall laugh.’ Here you have Prudence, whose part it is to weep, so far as present things are concerned, and to seek things which are eternal. ‘Blessed are ye when men shall hate you.’ Here you have Fortitude.”

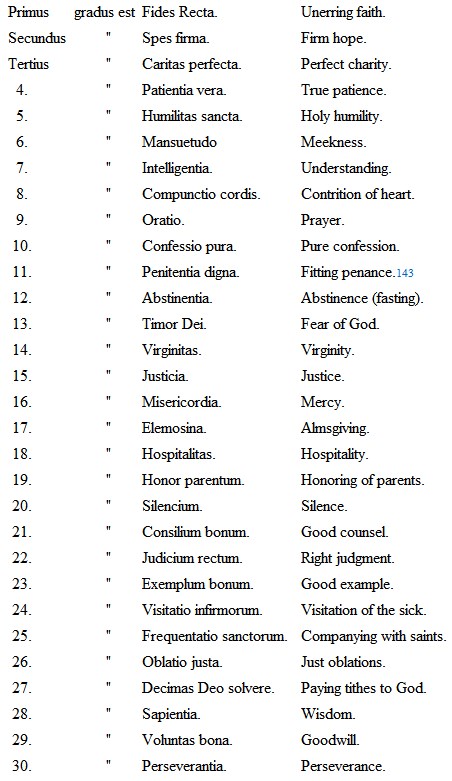

§ LIII. As a preparation for this profitable exercise of wit, we have also a reconciliation of the Beatitudes as stated by St. Matthew, with those of St. Luke, on the ground that “in those eight are these four, and in these four are those eight;” with sundry remarks on the mystical value of the number eight, with which I need not trouble the reader. With St. Ambrose, however, this puerile systematization is quite subordinate to a very forcible and truthful exposition of the real nature of the Christian life. But the classification he employs furnishes ground for farther subtleties to future divines; and in a MS. of the thirteenth century I find some expressions in this commentary on St. Luke, and in the treatise on the duties of bishops, amplified into a treatise on the “Steps of the Virtues: by which every one who perseveres may, by a straight path, attain to the heavenly country of the Angels.” (“Liber de Gradibus Virtutum: quibus ad patriam angelorum supernam itinere recto ascenditur ab omni perseverante.”) These Steps are thirty in number (one expressly for each day of the month), and the curious mode of their association renders the list well worth quoting:—

§ LIV.

[143] Or Penitence: but I rather think this is understood only in Compunctio cordis.

§ LV. The reader will note that the general idea of Christian virtue embodied in this list is true, exalted, and beautiful; the points of weakness being the confusion of duties with virtues, and the vain endeavor to enumerate the various offices of charity as so many separate virtues; more frequently arranged as seven distinct works of mercy. This general tendency to a morbid accuracy of classification was associated, in later times, with another very important element of the Renaissance mind, the love of personification; which appears to have reached its greatest vigor in the course of the sixteenth century, and is expressed to all future ages, in a consummate manner, in the poem of Spenser. It is to be noted that personification is, in some sort, the reverse of symbolism, and is far less noble. Symbolism is the setting forth of a great truth by an imperfect and inferior sign (as, for instance, of the hope of the resurrection by the form of the phœnix); and it is almost always employed by men in their most serious moods of faith, rarely in recreation. Men who use symbolism forcibly are almost always true believers in what they symbolize. But Personification is the bestowing of a human or living form upon an abstract idea: it is, in most cases, a mere recreation of the fancy, and is apt to disturb the belief in the reality of the thing personified. Thus symbolism constituted the entire system of the Mosaic dispensation: it occurs in every word of Christ’s teaching; it attaches perpetual mystery to the last and most solemn act of His life. But I do not recollect a single instance of personification in any of His words. And as we watch, thenceforward, the history of the Church, we shall find the declension of its faith exactly marked by the abandonment of symbolism,141 and the profuse employment of personification,—even to such an extent that the virtues came, at last, to be confused with the saints; and we find in the later Litanies, St. Faith, St. Hope, St. Charity, and St. Chastity, invoked immediately after St. Clara and St. Bridget.

§ LVI. Nevertheless, in the hands of its early and earnest masters, in whom fancy could not overthrow the foundations of faith, personification is, often thoroughly noble and lovely; the earlier conditions of it being just as much more spiritual and vital than the later ones, as the still earlier symbolism was more spiritual than they. Compare, for instance, Dante’s burning Charity, running and returning at the wheels of the chariot of God,—

“So ruddy, that her form had scarceBeen known within a furnace of clear flame,”with Reynolds’s Charity, a nurse in a white dress, climbed upon by three children.142 And not only so, but the number and nature of the virtues differ considerably in the statements of different poets and painters, according to their own views of religion, or to the manner of life they had it in mind to illustrate. Giotto, for instance, arranges his system altogether differently at Assisi, where he is setting forth the monkish life, and in the Arena Chapel, where he treats of that of mankind in general, and where, therefore, he gives only the so-called theological and cardinal virtues; while, at Assisi, the three principal virtues are those which are reported to have appeared in vision to St. Francis, Chastity, Obedience, and Poverty: Chastity being attended by Fortitude, Purity, and Penance; Obedience by Prudence and Humility; Poverty by Hope and Charity. The systems vary with almost every writer, and in almost every important work of art which embodies them, being more or less spiritual according to the power of intellect by which they were conceived. The most noble in literature are, I suppose, those of Dante and Spenser: and with these we may compare five of the most interesting series in the early art of Italy; namely, those of Orcagna, Giotto, and Simon Memmi, at Florence and Padua, and those of St. Mark’s and the Ducal Palace at Venice. Of course, in the richest of these series, the vices are personified together with the virtues, as in the Ducal Palace; and by the form or name of opposed vice, we may often ascertain, with much greater accuracy than would otherwise be possible, the particular idea of the contrary virtue in the mind of the writer or painter. Thus, when opposed to Prudence, or Prudentia, on the one side, we find Folly, or Stultitia, on the other, it shows that the virtue understood by Prudence, is not the mere guiding or cardinal virtue, but the Heavenly Wisdom,143 opposed to that folly which “hath said in its heart, there is no God;” and of which it is said, “the thought of foolishness is sin;” and again, “Such as be foolish shall not stand in thy sight.” This folly is personified, in early painting and illumination, by a half-naked man, greedily eating an apple or other fruit, and brandishing a club; showing that sensuality and violence are the two principal characteristics of Foolishness, and lead into atheism. The figure, in early Psalters, always forms the letter D, which commences the fifty-third Psalm, “Dixit insipiens.”

§ LVII. In reading Dante, this mode of reasoning from contraries is a great help, for his philosophy of the vices is the only one which admits of classification; his descriptions of virtue, while they include the ordinary formal divisions, are far too profound and extended to be brought under definition. Every line of the “Paradise” is full of the most exquisite and spiritual expressions of Christian truth; and that poem is only less read than the “Inferno” because it requires far greater attention, and, perhaps, for its full enjoyment, a holier heart.

§ LVIII. His system in the “Inferno” is briefly this. The whole nether world is divided into seven circles, deep within deep, in each of which, according to its depth, severer punishment is inflicted. These seven circles, reckoning them downwards, are thus allotted:

1. To those who have lived virtuously, but knew not Christ.

2. To Lust.

3. To Gluttony.

4. To Avarice and Extravagance.

5. To Anger and Sorrow.

6. To Heresy.

7. To Violence and Fraud.

This seventh circle is divided into two parts; of which the first, reserved for those who have been guilty of Violence, is again divided into three, apportioned severally to those who have committed, or desired to commit, violence against their neighbors, against themselves, or against God.

The lowest hell, reserved for the punishment of Fraud, is itself divided into ten circles, wherein are severally punished the sins of,—

1. Betraying women.

2. Flattery.

3. Simony.

4. False prophecy.

5. Peculation.

6. Hypocrisy.

7. Theft.

8. False counsel.

9. Schism and Imposture.

10. Treachery to those who repose entire trust in the traitor.

§ LIX. There is, perhaps, nothing more notable in this most interesting system than the profound truth couched under the attachment of so terrible a penalty to sadness or sorrow. It is true that Idleness does not elsewhere appear in the scheme, and is evidently intended to be included in the guilt of sadness by the word “accidioso;” but the main meaning of the poet is to mark the duty of rejoicing in God, according both to St. Paul’s command, and Isaiah’s promise, “Thou meetest him that rejoiceth and worketh righteousness.”144 I do not know words that might with more benefit be borne with us, and set in our hearts momentarily against the minor regrets and rebelliousnesses of life, than these simple ones:

“Tristi fummoNel aer dolce, che del sol s’allegra,Or ci attristiam, nella belletta negra.”“We once were sad,In the sweet air, made gladsome by the sun,Now in these murky settlings are we sad.”145Cary.The virtue usually opposed to this vice of sullenness is Alacritas, uniting the sense of activity and cheerfulness. Spenser has cheerfulness simply, in his description, never enough to be loved or praised, of the virtues of Womanhood; first feminineness or womanhood in specialty; then,—

“Next to her sate goodly Shamefastnesse,Ne ever durst, her eyes from ground upreare,Ne ever once did looke up from her desse,146As if some blame of evill she did feareThat in her cheekes made roses oft appeare:And her against sweet Cherefulnesse was placed,Whose eyes, like twinkling stars in evening cleare,Were deckt with smyles that all sad humours chaced.“And next to her sate sober Modestie,Holding her hand upon her gentle hart;And her against, sate comely Curtesie,That unto every person knew her part;And her before was seated overthwartSoft Silence, and submisse Obedience,Both linckt together never to dispart.”§ LX. Another notable point in Dante’s system is the intensity of uttermost punishment given to treason, the peculiar sin of Italy, and that to which, at this day, she attributes her own misery with her own lips. An Italian, questioned as to the causes of the failure of the campaign of 1848, always makes one answer, “We were betrayed;” and the most melancholy feature of the present state of Italy is principally this, that she does not see that, of all causes to which failure might be attributed, this is at once the most disgraceful, and the most hopeless. In fact, Dante seems to me to have written almost prophetically, for the instruction of modern Italy, and chiefly so in the sixth canto of the “Purgatorio.”

§ LXI. Hitherto we have been considering the system of the “Inferno” only. That of the “Purgatorio” is much simpler, it being divided into seven districts, in which the souls are severally purified from the sins of Pride, Envy, Wrath, Indifference, Avarice, Gluttony, and Lust; the poet thus implying in opposition, and describing in various instances, the seven virtues of Humility, Kindness,147 Patience, Zeal, Poverty, Abstinence, and Chastity, as adjuncts of the Christian character, in which it may occasionally fail, while the essential group of the three theological and four cardinal virtues are represented as in direct attendance on the chariot of the Deity; and all the sins of Christians are in the seventeenth canto traced to the deficiency or aberration of Affection.

§ LXII. The system of Spenser is unfinished, and exceedingly complicated, the same vices and virtues occurring under different forms in different places, in order to show their different relations to each other. I shall not therefore give any general sketch of it, but only refer to the particular personification of each virtue in order to compare it with that of the Ducal Palace.148 The peculiar superiority of his system is in its exquisite setting forth of Chastity under the figure of Britomart; not monkish chastity, but that of the purest Love. In completeness of personification no one can approach him; not even in Dante do I remember anything quite so great as the description of the Captain of the Lusts of the Flesh:

“As pale and wan as ashes was his looke;His body lean and meagre as a rake;And skin all withered like a dryed rooke;Thereto as cold and drery as a snake;That seemed to tremble evermore, and quake:All in a canvas thin he was bedight,And girded with a belt of twisted brake:Upon his head he wore an helmet light,Made of a dead man’s skull.”He rides upon a tiger, and in his hand is a bow, bent;

“And many arrows under his right side,Headed with flint, and fethers bloody dide.”The horror and the truth of this are beyond everything that I know, out of the pages of Inspiration. Note the heading of the arrows with flint, because sharper and more subtle in the edge than steel, and because steel might consume away with rust, but flint not; and consider in the whole description how the wasting away of body and soul together, and the coldness of the heart, which unholy fire has consumed into ashes, and the loss of all power, and the kindling of all terrible impatience, and the implanting of thorny and inextricable griefs, are set forth by the various images, the belt of brake, the tiger steed, and the light helmet, girding the head with death.

§ LXIII. Perhaps the most interesting series of the Virtues expressed in Italian art are those above mentioned of Simon Memmi in the Spanish chapel at Florence, of Ambrogio di Lorenzo in the Palazzo Publico of Pisa, of Orcagna in Or San Michele at Florence, of Giotto at Padua and Assisi, in mosaic on the central cupola of St. Mark’s, and in sculpture on the pillars of the Ducal Palace. The first two series are carefully described by Lord Lindsay; both are too complicated for comparison with the more simple series of the Ducal Palace; the other four of course agree in giving first the cardinal and evangelical virtues; their variations in the statement of the rest will be best understood by putting them in a parallel arrangement.