полная версия

полная версияThe Stones of Venice, Volume 2 (of 3)

§ LXIII. But of all these branches the most important are the inlaying and mosaic of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, represented in a central manner by these mosaics of St. Mark’s. Missal-painting could not, from its minuteness, produce the same sublime impressions, and frequently merged itself in mere ornamentation of the page. Modern book-illustration has been so little skilful as hardly to be worth naming. Sculpture, though in some positions it becomes of great importance, has always a tendency to lose itself in architectural effect; and was probably seldom deciphered, in all its parts, by the common people, still less the traditions annealed in the purple burning of the painted window. Finally, tempera pictures and frescoes were often of limited size or of feeble color. But the great mosaics of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries covered the walls and roofs of the churches with inevitable lustre; they could not be ignored or escaped from; their size rendered them majestic, their distance mysterious, their color attractive. They did not pass into confused or inferior decorations; neither were they adorned with any evidences of skill or science, such as might withdraw the attention from their subjects. They were before the eyes of the devotee at every interval of his worship; vast shadowings forth of scenes to whose realization he looked forward, or of spirits whose presence he invoked. And the man must be little capable of receiving a religious impression of any kind, who, to this day, does not acknowledge some feeling of awe, as he looks up at the pale countenances and ghastly forms which haunt the dark roofs of the Baptisteries of Parma and Florence, or remains altogether untouched by the majesty of the colossal images of apostles, and of Him who sent apostles, that look down from the darkening gold of the domes of Venice and Pisa.

§ LXIV. I shall, in a future portion of this work, endeavor to discover what probabilities there are of our being able to use this kind of art in modern churches; but at present it remains for us to follow out the connexion of the subjects represented in St. Mark’s so as to fulfil our immediate object, and form an adequate conception of the feelings of its builders, and of its uses to those for whom it was built.

Now there is one circumstance to which I must, in the outset, direct the reader’s special attention, as forming a notable distinction between ancient and modern days. Our eyes are now familiar and wearied with writing; and if an inscription is put upon a building, unless it be large and clear, it is ten to one whether we ever trouble ourselves to decipher it. But the old architect was sure of readers. He knew that every one would be glad to decipher all that he wrote; that they would rejoice in possessing the vaulted leaves of his stone manuscript; and that the more he gave them, the more grateful would the people be. We must take some pains, therefore, when we enter St. Mark’s, to read all that is inscribed, or we shall not penetrate into the feeling either of the builder or of his times.

§ LXV. A large atrium or portico is attached to two sides of the church, a space which was especially reserved for unbaptized persons and new converts. It was thought right that, before their baptism, these persons should be led to contemplate the great facts of the Old Testament history; the history of the Fall of Man, and of the lives of Patriarchs up to the period of the Covenant by Moses: the order of the subjects in this series being very nearly the same as in many Northern churches, but significantly closing with the Fall of the Manna, in order to mark to the catechumen the insufficiency of the Mosaic covenant for salvation,—“Our fathers did eat manna in the wilderness, and are dead,”—and to turn his thoughts to the true Bread of which that manna was the type.

§ LXVI. Then, when after his baptism he was permitted to enter the church, over its main entrance he saw, on looking back, a mosaic of Christ enthroned, with the Virgin on one side and St. Mark on the other, in attitudes of adoration. Christ is represented as holding a book open upon his knee, on which is written: “I am the door; by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved.” On the red marble moulding which surrounds the mosaic is written: “I am the gate of life; Let those who are mine enter by me.” Above, on the red marble fillet which forms the cornice of the west end of the church, is written, with reference to the figure of Christ below: “Who he was, and from whom he came, and at what price he redeemed thee, and why he made thee, and gave thee all things, do thou consider.”

Now observe, this was not to be seen and read only by the catechumen when he first entered the church; every one who at any time entered, was supposed to look back and to read this writing; their daily entrance into the church was thus made a daily memorial of their first entrance into the spiritual Church; and we shall find that the rest of the book which was opened for them upon its walls continually led them in the same manner to regard the visible temple as in every part a type of the invisible Church of God.

§ LXVII. Therefore the mosaic of the first dome, which is over the head of the spectator as soon as he has entered by the great door (that door being the type of baptism), represents the effusion of the Holy Spirit, as the first consequence and seal of the entrance into the Church of God. In the centre of the cupola is the Dove, enthroned in the Greek manner, as the Lamb is enthroned, when the Divinity of the Second and Third Persons is to be insisted upon together with their peculiar offices. From the central symbol of the Holy Spirit twelve streams of fire descend upon the heads of the twelve apostles, who are represented standing around the dome; and below them, between the windows which are pierced in its walls, are represented, by groups of two figures for each separate people, the various nations who heard the apostles speak, at Pentecost, every man in his own tongue. Finally, on the vaults, at the four angles which support the cupola, are pictured four angels, each bearing a tablet upon the end of a rod in his hand: on each of the tablets of the three first angels is inscribed the word “Holy;” on that of the fourth is written “Lord;” and the beginning of the hymn being thus put into the mouths of the four angels, the words of it are continued around the border of the dome, uniting praise to God for the gift of the Spirit, with welcome to the redeemed soul received into His Church:

“Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth:Heaven and Earth are full of thy Glory.Hosanna in the Highest:Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord.”And observe in this writing that the convert is required to regard the outpouring of the Holy Spirit especially as a work of sanctification. It is the holiness of God manifested in the giving of His Spirit to sanctify those who had become His children, which the four angels celebrate in their ceaseless praise; and it is on account of this holiness that the heaven and earth are said to be full of His glory.

§ LXVIII. After thus hearing praise rendered to God by the angels for the salvation of the newly-entered soul, it was thought fittest that the worshipper should be led to contemplate, in the most comprehensive forms possible, the past evidence and the future hopes of Christianity, as summed up in three facts without assurance of which all faith is vain; namely that Christ died, that He rose again, and that He ascended into heaven, there to prepare a place for His elect. On the vault between the first and second cupolas are represented the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, with the usual series of intermediate scenes,—the treason of Judas, the judgment of Pilate, the crowning with thorns, the descent into Hades, the visit of the women to the sepulchre, and the apparition to Mary Magdalene. The second cupola itself, which is the central and principal one of the church, is entirely occupied by the subject of the Ascension. At the highest point of it Christ is represented as rising into the blue heaven, borne up by four angels, and throned upon a rainbow, the type of reconciliation. Beneath him, the twelve apostles are seen upon the Mount of Olives, with the Madonna, and, in the midst of them, the two men in white apparel who appeared at the moment of the Ascension, above whom, as uttered by them, are inscribed the words, “Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven? This Christ, the Son of God, as He is taken from you, shall so come, the arbiter of the earth, trusted to do judgment and justice.”

§ LXIX. Beneath the circle of the apostles, between the windows of the cupola, are represented the Christian virtues, as sequent upon the crucifixion of the flesh, and the spiritual ascension together with Christ. Beneath them, on the vaults which support the angles of the cupola, are placed the four Evangelists, because on their evidence our assurance of the fact of the ascension rests; and, finally, beneath their feet, as symbols of the sweetness and fulness of the Gospel which they declared, are represented the four rivers of Paradise, Pison, Gihon, Tigris, and Euphrates.

§ LXX. The third cupola, that over the altar, represents the witness of the Old Testament to Christ; showing him enthroned in its centre, and surrounded by the patriarchs and prophets. But this dome was little seen by the people;38 their contemplation was intended to be chiefly drawn to that of the centre of the church, and thus the mind of the worshipper was at once fixed on the main groundwork and hope of Christianity,—“Christ is risen,” and “Christ shall come.” If he had time to explore the minor lateral chapels and cupolas, he could find in them the whole series of New Testament history, the events of the Life of Christ, and the Apostolic miracles in their order, and finally the scenery of the Book of Revelation;39 but if he only entered, as often the common people do to this hour, snatching a few moments before beginning the labor of the day to offer up an ejaculatory prayer, and advanced but from the main entrance as far as the altar screen, all the splendor of the glittering nave and variegated dome, if they smote upon his heart, as they might often, in strange contrast with his reed cabin among the shallows of the lagoon, smote upon it only that they might proclaim the two great messages—“Christ is risen,” and “Christ shall come.” Daily, as the white cupolas rose like wreaths of sea-foam in the dawn, while the shadowy campanile and frowning palace were still withdrawn into the night, they rose with the Easter Voice of Triumph,—“Christ is risen;” and daily, as they looked down upon the tumult of the people, deepening and eddying in the wide square that opened from their feet to the sea, they uttered above them the sentence of warning,—“Christ shall come.”

§ LXXXI. And this thought may surely dispose the reader to look with some change of temper upon the gorgeous building and wild blazonry of that shrine of St. Mark’s. He now perceives that it was in the hearts of the old Venetian people far more than a place of worship. It was at once a type of the Redeemed Church of God, and a scroll for the written word of God. It was to be to them, both an image of the Bride, all glorious within, her clothing of wrought gold; and the actual Table of the Law and the Testimony, written within and without. And whether honored as the Church or as the Bible, was it not fitting that neither the gold nor the crystal should be spared in the adornment of it; that, as the symbol of the Bride, the building of the wall thereof should be of jasper,40 and the foundations of it garnished with all manner of precious stones; and that, as the channel of the World, that triumphant utterance of the Psalmist should be true of it,—“I have rejoiced in the way of thy testimonies, as much as in all riches?” And shall we not look with changed temper down the long perspective of St. Mark’s Place towards the sevenfold gates and glowing domes of its temple, when we know with what solemn purpose the shafts of it were lifted above the pavement of the populous square? Men met there from all countries of the earth, for traffic or for pleasure; but, above the crowd swaying for ever to and fro in the restlessness of avarice or thirst of delight, was seen perpetually the glory of the temple, attesting to them, whether they would hear or whether they would forbear, that there was one treasure which the merchantmen might buy without a price, and one delight better than all others, in the word and the statutes of God. Not in the wantonness of wealth, not in vain ministry to the desire of the eyes or the pride of life, were those marbles hewn into transparent strength, and those arches arrayed in the colors of the iris. There is a message written in the dyes of them, that once was written in blood; and a sound in the echoes of their vaults, that one day shall fill the vault of heaven,—“He shall return, to do judgment and justice.” The strength of Venice was given her, so long as she remembered this: her destruction found her when she had forgotten this; and it found her irrevocably, because she forgot it without excuse. Never had city a more glorious Bible. Among the nations of the North, a rude and shadowy sculpture filled their temples with confused and hardly legible imagery; but, for her, the skill and the treasures of the East had gilded every letter, and illumined every page, till the Book-Temple shone from afar off like the star of the Magi. In other cities, the meetings of the people were often in places withdrawn from religious association, subject to violence and to change; and on the grass of the dangerous rampart, and in the dust of the troubled street, there were deeds done and counsels taken, which, if we cannot justify, we may sometimes forgive. But the sins of Venice, whether in her palace or in her piazza, were done with the Bible at her right hand. The walls on which its testimony was written were separated but by a few inches of marble from those which guarded the secrets of her councils, or confined the victims of her policy. And when in her last hours she threw off all shame and all restraint, and the great square of the city became filled with the madness of the whole earth, be it remembered how much her sin was greater, because it was done in the face of the House of God, burning with the letters of His Law. Mountebank and masquer laughed their laugh, and went their way; and a silence has followed them, not unforetold; for amidst them all, through century after century of gathering vanity and festering guilt, that white dome of St. Mark’s had uttered in the dead ear of Venice, “Know thou, that for all these things God will bring thee into judgment.”

CHAPTER V.

BYZANTINE PALACES

§ I. The account of the architecture of St. Mark’s given in the previous chapter has, I trust, acquainted the reader sufficiently with the spirit of the Byzantine style: but he has probably, as yet, no clear idea of its generic forms. Nor would it be safe to define these after an examination of St. Mark’s alone, built as it was upon various models, and at various periods. But if we pass through the city, looking for buildings which resemble St. Mark’s—first, in the most important feature of incrustation; secondly, in the character of the mouldings,—we shall find a considerable number, not indeed very attractive in their first address to the eye, but agreeing perfectly, both with each other, and with the earliest portions of St. Mark’s, in every important detail; and to be regarded, therefore, with profound interest, as indeed the remains of an ancient city of Venice, altogether different in aspect from that which now exists. From these remains we may with safety deduce general conclusions touching the forms of Byzantine architecture, as practised in Eastern Italy, during the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries.

§ II. They agree in another respect, as well as in style. All are either ruins, or fragments disguised by restoration. Not one of them is uninjured or unaltered; and the impossibility of finding so much as an angle or a single story in perfect condition is a proof, hardly less convincing than the method of their architecture, that they were indeed raised during the earliest phases of the Venetian power. The mere fragments, dispersed in narrow streets, and recognizable by a single capital, or the segment of an arch, I shall not enumerate: but, of important remains, there are six in the immediate neighborhood of the Rialto, one in the Rio di Ca’ Foscari, and one conspicuously placed opposite the great Renaissance Palace known as the Vendramin Calerghi, one of the few palaces still inhabited41 and well maintained; and noticeable, moreover, as having a garden beside it, rich with evergreens, and decorated by gilded railings and white statues that cast long streams of snowy reflection down into the deep water. The vista of canal beyond is terminated by the Church of St. Geremia, another but less attractive work of the Renaissance; a mass of barren brickwork, with a dull leaden dome above, like those of our National Gallery. So that the spectator has the richest and meanest of the late architecture of Venice before him at once: the richest, let him observe, a piece of private luxury; the poorest, that which was given to God. Then, looking to the left, he will see the fragment of the work of earlier ages, testifying against both, not less by its utter desolation than by the nobleness of the traces that are still left of it.

§ III. It is a ghastly ruin; whatever is venerable or sad in its wreck being disguised by attempts to put it to present uses of the basest kind. It has been composed of arcades borne by marble shafts, and walls of brick faced with marble: but the covering stones have been torn away from it like the shroud from a corpse; and its walls, rent into a thousand chasms, are filled and refilled with fresh brickwork, and the seams and hollows are choked with clay and whitewash, oozing and trickling over the marble,—itself blanched into dusty decay by the frosts of centuries. Soft grass and wandering leafage have rooted themselves in the rents, but they are not suffered to grow in their own wild and gentle way, for the place is in a sort inhabited; rotten partitions are nailed across its corridors, and miserable rooms contrived in its western wing; and here and there the weeds are indolently torn down, leaving their haggard fibres to struggle again into unwholesome growth when the spring next stirs them: and thus, in contest between death and life, the unsightly heap is festering to its fall.

Of its history little is recorded, and that little futile. That it once belonged to the dukes of Ferrara, and was bought from them in the sixteenth century, to be made a general receptacle for the goods of the Turkish merchants, whence it is now generally known as the Fondaco, or Fontico, de’ Turchi, are facts just as important to the antiquary, as that, in the year 1852, the municipality of Venice allowed its lower story to be used for a “deposito di Tabacchi.” Neither of this, nor of any other remains of the period, can we know anything but what their own stones will tell us.

§ IV. The reader will find in Appendix 11, written chiefly for the traveller’s benefit, an account of the situation and present state of the other seven Byzantine palaces. Here I shall only give a general account of the most interesting points in their architecture.

They all agree in being round-arched and incrusted with marble, but there are only six in which the original disposition of the parts is anywise traceable; namely, those distinguished in the Appendix as the Fondaco de’ Turchi, Casa Loredan, Caso Farsetti, Rio-Foscari House, Terraced House, and Madonnetta House:42 and these six agree farther in having continuous arcades along their entire fronts from one angle to the other, and in having their arcades divided, in each case, into a centre and wings; both by greater size in the midmost arches, and by the alternation of shafts in the centre, with pilasters, or with small shafts, at the flanks.

§ V. So far as their structure can be traced, they agree also in having tall and few arches in their lower stories, and shorter and more numerous arches above: but it happens most unfortunately that in the only two cases in which the second stories are left the ground floors are modernized, and in the others where the sea stories are left the second stories are modernized; so that we never have more than two tiers of the Byzantine arches, one above the other. These, however, are quite enough to show the first main point on which I wish to insist, namely, the subtlety of the feeling for proportion in the Greek architects; and I hope that even the general reader will not allow himself to be frightened by the look of a few measurements, for, if he will only take the little pains necessary to compare them, he will, I am almost certain, find the result not devoid of interest.

Fig. IV.

§ VI. I had intended originally to give elevations of all these palaces; but have not had time to prepare plates requiring so much labor and care. I must, therefore, explain the position of their parts in the simplest way in my power.

The Fondaco de’ Turchi has sixteen arches in its sea story, and twenty-six above them in its first story, the whole based on a magnificent foundation, built of blocks of red marble, some of them seven feet long by a foot and a half thick, and raised to a height of about five feet above high-water mark. At this level, the elevation of one half of the building, from its flank to the central pillars of its arcades, is rudely given in Fig. IV., in the previous page. It is only drawn to show the arrangement of the parts, as the sculptures which are indicated by the circles and upright oblongs between the arches are too delicate to be shown in a sketch three times the size of this. The building once was crowned with an Arabian parapet; but it was taken down some years since, and I am aware of no authentic representation of its details. The greater part of the sculptures between the arches, indicated in the woodcut only by blank circles, have also fallen, or been removed, but enough remain on the two flanks to justify the representation given in the diagram of their original arrangement.

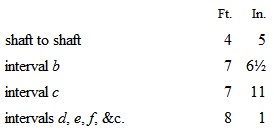

And now observe the dimensions. The small arches of the wings in the ground story, a, a, a, measure, in breadth, from

The difference between the width of the arches b and c is necessitated by the small recess of the cornice on the left hand as compared with that of the great capitals; but this sudden difference of half a foot between the two extreme arches of the centre offended the builder’s eye, so he diminished the next one, unnecessarily, two inches, and thus obtained the gradual cadence to the flanks, from eight feet down to four and a half, in a series of continually increasing steps. Of course the effect cannot be shown in the diagram, as the first difference is less than the thickness of its lines. In the upper story the capitals are all nearly of the same height, and there was no occasion for the difference between the extreme arches. Its twenty-six arches are placed, four small ones above each lateral three of the lower arcade, and eighteen larger above the central ten; thus throwing the shafts into all manner of relative positions, and completely confusing the eye in any effort to count them: but there is an exquisite symmetry running through their apparent confusion; for it will be seen that the four arches in each flank are arranged in two groups, of which one has a large single shaft in the centre, and the other a pilaster and two small shafts. The way in which the large shaft is used as an echo of those in the central arcade, dovetailing them, as it were, into the system of the pilasters,—just as a great painter, passing from one tone of color to another, repeats, over a small space, that which he has left,—is highly characteristic of the Byzantine care in composition. There are other evidences of it in the arrangement of the capitals, which will be noticed below in the seventh chapter. The lateral arches of this upper arcade measure 3 ft. 2 in. across, and the central 3 ft. 11 in., so that the arches in the building are altogether of six magnitudes.