полная версия

полная версияThe Stones of Venice, Volume 1 (of 3)

The first reference to the “Seven Lamps” is in the second page, where Mr. Garbett asks a question, “Why are not convenience and stability enough to constitute a fine building?”—which I should have answered shortly by asking another, “Why we have been made men, and not bees nor termites:” but Mr. Garbett has given a very pretty, though partial, answer to it himself, in his 4th to 9th pages,—an answer which I heartily beg the reader to consider. But, in page 12, it is made a grave charge against me, that I use the words beauty and ornament interchangeably. I do so, and ever shall; and so, I believe, one day, will Mr. Garbett himself; but not while he continues to head his pages thus:—“Beauty not dependent on ornament, or superfluous features.” What right has he to assume that ornament, rightly so called, ever was, or can be, superfluous? I have said before, and repeatedly in other places, that the most beautiful things are the most useless; I never said superfluous. I said useless in the well-understood and usual sense, as meaning, inapplicable to the service of the body. Thus I called peacocks and lilies useless; meaning, that roast peacock was unwholesome (taking Juvenal’s word for it), and that dried lilies made bad hay: but I do not think peacocks superfluous birds, nor that the world could get on well without its lilies. Or, to look closer, I suppose the peacock’s blue eyes to be very useless to him; not dangerous indeed, as to their first master, but of small service, yet I do not think there is a superfluous eye in all his tail; and for lilies, though the great King of Israel was not “arrayed” like one of them, can Mr. Garbett tell us which are their superfluous leaves? Is there no Diogenes among lilies? none to be found content to drink dew, but out of silver? The fact is, I never met with the architect yet who did not think ornament meant a thing to be bought in a shop and pinned on, or left off, at architectural toilets, as the fancy seized them, thinking little more than many women do of the other kind of ornament—the only true kind,—St. Peter’s kind,—“Not that outward adorning, but the inner—of the heart.” I do not mean that architects cannot conceive this better ornament, but they do not understand that it is the only ornament; that all architectural ornament is this, and nothing but this; that a noble building never has any extraneous or superfluous ornament; that all its parts are necessary to its loveliness, and that no single atom of them could be removed without harm to its life. You do not build a temple and then dress it.101 You create it in its loveliness, and leave it, as her Maker left Eve. Not unadorned, I believe, but so well adorned as to need no feather crowns. And I use the words ornament and beauty interchangeably, in order that architects may understand this: I assume that their building is to be a perfect creature capable of nothing less than it has, and needing nothing more. It may, indeed, receive additional decoration afterwards, exactly as a woman may gracefully put a bracelet on her arm, or set a flower in her hair: but that additional decoration is not the architecture. It is of curtains, pictures, statues, things that may be taken away from the building, and not hurt it. What has the architect to do with these? He has only to do with what is part of the building itself, that is to say, its own inherent beauty. And because Mr. Garbett does not understand or acknowledge this, he is led on from error to error; for we next find him endeavoring to define beauty as distinct from ornament, and saying that “Positive beauty may be produced by a studious collation of whatever will display design, order, and congruity.” (p. 14.) Is that so? There is a highly studious collation of whatever will display design, order, and congruity, in a skull, is there not?—yet small beauty. The nose is a decorative feature,—yet slightly necessary to beauty, it seems to me; now, at least, for I once thought I must be wrong in considering a skull disagreeable. I gave it fair trial: put one on my bed-room chimney-piece, and looked at it by sunrise every morning, and by moonlight every night, and by all the best lights I could think of, for a month, in vain. I found it as ugly at last as I did at first. So, also, the hair is a decoration, and its natural curl is of little use; but can Mr. Garbett conceive a bald beauty; or does he prefer a wig, because that is a “studious collation” of whatever will produce design, order, and congruity? So the flush of the cheek is a decoration,—God’s painting of the temple of his spirit,—and the redness of the lip; and yet poor Viola thought it beauty truly blent; and I hold with her.

I have answered enough to this count.

The second point questioned is my assertion, “Ornament cannot be overcharged if it is good, and is always overcharged when it is bad.” To which Mr. Garbett objects in these terms: “I must contend, on the contrary, that the very best ornament may be overcharged by being misplaced.”

A short sentence with two mistakes in it.

First. Mr. Garbett cannot get rid of his unfortunate notion that ornament is a thing to be manufactured separately, and fastened on. He supposes that an ornament may be called good in itself, in the stonemason’s yard or in the ironmonger’s shop: Once for all, let him put this idea out of his head. We may say of a thing, considered separately, that it is a pretty thing; but before we can say it is a good ornament, we must know what it is to adorn, and how. As, for instance, a ring of gold is a pretty thing; it is a good ornament on a woman’s finger; not a good ornament hung through her under lip. A hollyhock, seven feet high, would be a good ornament for a cottage-garden; not a good ornament for a lady’s head-dress. Might not Mr. Garbett have seen this without my showing? and that, therefore, when I said “good” ornament, I said “well-placed” ornament, in one word, and that, also, when Mr. Garbett says “it may be overcharged by being misplaced,” he merely says it may be overcharged by being bad.

Secondly. But, granted that ornament were independent of its position, and might be pronounced good in a separate form, as books are good, or men are good.—Suppose I had written to a student in Oxford, “You cannot have too many books, if they be good books;” and he had answered me, “Yes, for if I have many, I have no place to put them in but the coal-cellar.” Would that in anywise affect the general principle that he could not have too many books?

Or suppose he had written, “I must not have too many, they confuse my head.” I should have written back to him: “Don’t buy books to put in the coal-hole, nor read them if they confuse your head; you cannot have too many, if they be good: but if you are too lazy to take care of them, or too dull to profit by them, you are better without them.”

Exactly in the same tone, I repeat to Mr. Garbett, “You cannot have too much ornament, if it be good: but if you are too indolent to arrange it, or too dull to take advantage of it, assuredly you are better without it.”

The other points bearing on this question have already been stated in the close of the 21st chapter.

The third reference I have to answer, is to my repeated assertion, that the evidence of manual labor is one of the chief sources of value in ornament, (“Seven Lamps,” p. 49, “Modern Painters,” § 1, Chap. III.,) to which objection is made in these terms: “We must here warn the reader against a remarkable error of Ruskin. The value of ornaments in architecture depends not in the slightest degree on the manual labor they contain. If it did, the finest ornaments ever executed would be the stone chains that hang before certain Indian rock-temples.” Is that so? Hear a parallel argument. “The value of the Cornish mines depends not in the slightest degree on the quantity of copper they contain. If it did, the most valuable things ever produced would be copper saucepans.” It is hardly worth my while to answer this; but, lest any of my readers should be confused by the objection, and as I hold the fact to be of great importance, I may re-state it for them with some explanation.

Observe, then, the appearance of labor, that is to say, the evidence of the past industry of man, is always, in the abstract, intensely delightful: man being meant to labor, it is delightful to see that he has labored, and to read the record of his active and worthy existence.

The evidence of labor becomes painful only when it is a sign of Evil greater, as Evil, than the labor is great, as Good. As, for instance, if a man has labored for an hour at what might have been done by another man in a moment, this evidence of his labor is also evidence of his weakness; and this weakness is greater in rank of evil, than his industry is great in rank of good.

Again, if a man have labored at what was not worth accomplishing, the signs of his labor are the signs of his folly, and his folly dishonors his industry; we had rather he had been a wise man in rest than a fool in labor.

Again, if a man have labored without accomplishing anything, the signs of his labor are the signs of his disappointment; and we have more sorrow in sympathy with his failure, than pleasure in sympathy with his work.

Now, therefore, in ornament, whenever labor replaces what was better than labor, that is to say, skill and thought; wherever it substitutes itself for these, or negatives these by its existence, then it is positive evil. Copper is an evil when it alloys gold, or poisons food: not an evil, as copper; good in the form of pence, seriously objectionable when it occupies the room of guineas. Let Danaë cast it out of her lap, when the gold comes from heaven; but let the poor man gather it up carefully from the earth.

Farther, the evidence of labor is not only a good when added to other good, but the utter absence of it destroys good in human work. It is only good for God to create without toil; that which man can create without toil is worthless: machine ornaments are no ornaments at all. Consider this carefully, reader: I could illustrate it for you endlessly; but you feel it yourself every hour of your existence. And if you do not know that you feel it, take up, for a little time, the trade which of all manual trades has been most honored: be for once a carpenter. Make for yourself a table or a chair, and see if you ever thought any table or chair so delightful, and what strange beauty there will be in their crooked limbs.

I have not noticed any other animadversions on the “Seven Lamps” in Mr. Garbett’s volume; but if there be more, I must now leave it to his own consideration, whether he may not, as in the above instances, have made them incautiously: I may, perhaps, also be permitted to request other architects, who may happen to glance at the preceding pages, not immediately to condemn what may appear to them false in general principle. I must often be found deficient in technical knowledge; I may often err in my statements respecting matters of practice or of special law. But I do not write thoughtlessly respecting principles; and my statements of these will generally be found worth reconnoitring before attacking. Architects, no doubt, fancy they have strong grounds for supposing me wrong when they seek to invalidate my assertions. Let me assure them, at least, that I mean to be their friend, although they may not immediately recognise me as such. If I could obtain the public ear, and the principles I have advocated were carried into general practice, porphyry and serpentine would be given to them instead of limestone and brick; instead of tavern and shop-fronts they would have to build goodly churches and noble dwelling-houses; and for every stunted Grecism and stucco Romanism, into which they are now forced to shape their palsied thoughts, and to whose crumbling plagiarisms they must trust their doubtful fame, they would be asked to raise whole streets of bold, and rich, and living architecture, with the certainty in their hearts of doing what was honorable to themselves, and good for all men.

Before I altogether leave the question of the influence of labor on architectural effect, the reader may expect from me a word or two respecting the subject which this year must be interesting to all—the applicability, namely, of glass and iron to architecture in general, as in some sort exemplified by the Crystal Palace.

It is thought by many that we shall forthwith have great part of our architecture in glass and iron, and that new forms of beauty will result from the studied employment of these materials.

It may be told in a few words how far this is possible; how far eternally impossible.

There are two means of delight in all productions of art—color and form.

The most vivid conditions of color attainable by human art are those of works in glass and enamel, but not the most perfect. The best and noblest coloring possible to art is that attained by the touch of the human hand on an opaque surface, upon which it can command any tint required, without subjection to alteration by fire or other mechanical means. No color is so noble as the color of a good painting on canvas or gesso.

This kind of color being, however, impossible, for the most part, in architecture, the next best is the scientific disposition of the natural colors of stones, which are far nobler than any abstract hues producible by human art.

The delight which we receive from glass painting is one altogether inferior, and in which we should degrade ourselves by over indulgence. Nevertheless, it is possible that we may raise some palaces like Aladdin’s with colored glass for jewels, which shall be new in the annals of human splendor, and good in their place; but not if they superseded nobler edifices.

Now, color is producible either on opaque or in transparent bodies: but form is only expressible, in its perfection, on opaque bodies, without lustre.

This law is imperative, universal, irrevocable. No perfect or refined form can be expressed except in opaque and lustreless matter. You cannot see the form of a jewel, nor, in any perfection, even of a cameo or bronze. You cannot perfectly see the form of a humming-bird, on account of its burnishing; but you can see the form of a swan perfectly. No noble work in form can ever, therefore, be produced in transparent or lustrous glass or enamel. All noble architecture depends for its majesty on its form: therefore you can never have any noble architecture in transparent or lustrous glass or enamel. Iron is, however, opaque; and both it and opaque enamel may, perhaps, be rendered quite lustreless; and, therefore, fit to receive noble form.

Let this be thoroughly done, and both the iron and enamel made fine in paste or grain, and you may have an architecture as noble as cast or struck architecture even can be: as noble, therefore, as coins can be, or common cast bronzes, and such other multiplicable things;102—eternally separated from all good and great things by a gulph which not all the tubular bridges nor engineering of ten thousand nineteenth centuries cast into one great bronze-foreheaded century, will ever overpass one inch of. All art which is worth its room in this world, all art which is not a piece of blundering refuse, occupying the foot or two of earth which, if unencumbered by it, would have grown corn or violets, or some better thing, is art which proceeds from an individual mind, working through instruments which assist, but do not supersede, the muscular action of the human hand, upon the materials which most tenderly receive, and most securely retain, the impressions of such human labor.

And the value of every work of art is exactly in the ratio of the quantity of humanity which has been put into it, and legibly expressed upon it for ever:—

First, of thought and moral purpose;

Secondly, of technical skill;

Thirdly, of bodily industry.

The quantity of bodily industry which that Crystal Palace expresses is very great. So far it is good.

The quantity of thought it expresses is, I suppose, a single and very admirable thought of Mr. Paxton’s, probably not a bit brighter than thousands of thoughts which pass through his active and intelligent brain every hour,—that it might be possible to build a greenhouse larger than ever greenhouse was built before. This thought, and some very ordinary algebra, are as much as all that glass can represent of human intellect. “But one poor half-pennyworth of bread to all this intolerable deal of sack.” Alas!

“The earth hath bubbles as the water hath:And this is of them.”18. EARLY ENGLISH CAPITALS

The depth of the cutting in some of the early English capitals is, indeed, part of a general system of attempts at exaggerated force of effect, like the “black touches” of second-rate draughtsmen, which I have noticed as characteristic of nearly all northern work, associated with the love of the grotesque: but the main section of the capital is indeed a dripstone rolled round, as above described; and dripstone sections are continually found in northern work, where not only they cannot increase force of effect, but are entirely invisible except on close examination; as, for instance, under the uppermost range of stones of the foundation of Whitehall, or under the slope of the restored base of All Souls College, Oxford, under the level of the eye. I much doubt if any of the Fellows be aware of its existence.

Many readers will be surprised and displeased by the disparagement of the early English capital. That capital has, indeed, one character of considerable value; namely, the boldness with which it stops the mouldings which fall upon it, and severs them from the shaft, contrasting itself with the multiplicity of their vertical lines. Sparingly used, or seldom seen, it is thus, in its place, not unpleasing; and we English love it from association, it being always found in connection with our purest and loveliest Gothic arches, and never in multitudes large enough to satiate the eye with its form. The reader who sits in the Temple church every Sunday, and sees no architecture during the week but that of Chancery Lane, may most justifiably quarrel with me for what I have said of it. But if every house in Fleet Street or Chancery Lane were Gothic, and all had early English capitals, I would answer for his making peace with me in a fortnight.

19. TOMBS NEAR ST. ANASTASIA

Whose they are, is of little consequence to the reader or to me, and I have taken no pains to discover; their value being not in any evidence they bear respecting dates, but in their intrinsic merit as examples of composition. Two of them are within the gate, one on the top of it, and this latter is on the whole the best, though all are beautiful; uniting the intense northern energy in their figure sculpture with the most serene classical restraint in their outlines, and unaffected, but masculine simplicity of construction.

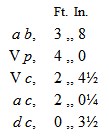

I have not put letters to the diagram of the lateral arch at page 154, in order not to interfere with the clearness of the curves, but I shall always express the same points by the same letters, whenever I have to give measures of arches of this simple kind, so that the reader need never have the diagrams lettered at all. The base or span of the centre arch will always be a b; its vertex will always be V; the points of the cusps will be c c; p p will be the bases of perpendiculars let fall from V and c on a b; and d the base of a perpendicular from the point of the cusp to the arch line. Then a b will always be a span of the arch, V p its perpendicular height, V a the chord of its side arcs, d c the depth of its cusps, c c the horizontal interval between the cusps, a c the length of the chord of the lower arc of the cusp, V c the length of the chord of the upper arc of the cusp, (whether continuous or not,) and c p the length of a perpendicular from the point of the cusp on a b.

Of course we do not want all these measures for a single arch, but it often happens that some of them are attainable more easily than others; some are often unattainable altogether, and it is necessary therefore to have expressions for whichever we may be able to determine.

V p or V a, a b, and d c are always essential; then either a c and V c or c c and c p: when I have my choice, I always take a b, V p, d c, c c, and c p, but c p is not to be generally obtained so accurately as the cusp arcs.

The measures of the present arch are:

20. SHAFTS OF DUCAL PALACE

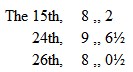

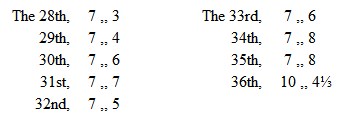

The shortness of the thicker ones at the angles is induced by the greater depth of the enlarged capitals: thus the 36th shaft is 10 ft. 4⅓ in. in circumference at its base, and 10 ,, 0½103 in circumference under the fillet of its capital; but it is only 6 ,, 1¾ high, while the minor intermediate shafts, of which the thickest is 7 ,, 8 round at the base, and 7 ,, 4 under capital, are yet on the average 7 ,, 7 high. The angle shaft towards the sea (the 18th) is nearly of the proportions of the 36th, and there are three others, the 15th, 24th, and 26th, which are thicker than the rest, though not so thick as the angle ones. The 24th and 26th have both party walls to bear, and I imagine the 15th must in old time have carried another, reaching across what is now the Sala del Gran Consiglio.

They measure respectively round at the base,

The other pillars towards the sea, and those to the 27th inclusive of the Piazzetta, are all seven feet round at the base, and then there is a most curious and delicate crescendo of circumference to the 36th, thus:

The shafts of the upper arcade, which are above these thicker columns, are also thicker than their companions, measuring on the average, 4 ,, 8½ in circumference, while those of the sea façade, except the 29th, average 4 ,, 7½ in circumference. The 29th, which is of course above the 15th of the lower story, is 5 ,, 5 in circumference, which little piece of evidence will be of no small value to us by-and-by. The 35th carries the angle of the palace, and is 6 ,, 0 round. The 47th, which comes above the 24th and carries the party wall of the Sala del Gran Consiglio, is strengthened by a pilaster; and the 51st, which comes over the 26th, is 5 ,, 4½ round, or nearly the same as the 29th; it carries the party wall of the Sala del Scrutinio; a small room containing part of St. Mark’s library, coming between the two saloons; a room which, in remembrances of the help I have received in all my inquiries from the kindness and intelligence of its usual occupant, I shall never easily distinguish otherwise than as “Mr. Lorenzi’s.”104

I may as well connect with these notes respecting the arcades of the Ducal Palace, those which refer to Plate XIV., which represents one of its spandrils. Every spandril of the lower arcade was intended to have been occupied by an ornament resembling the one given in that plate. The mass of the building being of Istrian stone, a depth of about two inches is left within the mouldings of the arches, rough hewn, to receive the slabs of fine marble composing the patterns. I cannot say whether the design was ever completed, or the marbles have been since removed, but there are now only two spandrils retaining their fillings, and vestiges of them in a third. The two complete spandrils are on the sea façade, above the 3rd and 10th capitals (vide method of numbering, Chap. I., page 30); that is to say, connecting the 2nd arch with the 3rd, and the 9th with the 10th. The latter is the one given in Plate XIV. The white portions of it are all white marble, the dental band surrounding the circle is in coarse sugary marble, which I believe to be Greek, and never found in Venice to my recollection, except in work at least anterior to the fifteenth century. The shaded fields charged with the three white triangles are of red Verona marble; the inner disc is green serpentine, and the dark pieces of the radiating leaves are grey marble. The three triangles are equilateral. The two uppermost are 1 ,, 5 each side, and the lower 1 ,, 2.