полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

2. Marriage.

Infant-marriage is in vogue, and polygamy is permitted only if the first wife be barren. The betrothal is cemented by an exchange of betel-leaves and areca-nuts between the fathers of the engaged couple. A bride-price of from ten to twenty rupees is usually paid. Some rice, a pice coin, 21 cowries and 21 pieces of turmeric are placed in the hole in which the marriage post is erected. When the wedding procession arrives at the girl’s house the bridegroom goes to the marriage-shed and pulls out the festoons of mango leaves, the bride’s family trying to prevent him by offering him a winnowing-fan. He then approaches the door of the house, behind which his future mother-in-law is standing, and slips a piece of cloth through the door for her. She takes this and retires without being seen. The wedding consists of the bhānwar ceremony or walking round the sacred pole. During the proceedings the women tie a new thread round the bridegroom’s neck to avert the evil eye. After the wedding the bride and bridegroom, in opposition to the usual custom, must return to the latter’s house on foot. In explanation of this they tell a story to the effect that the married couple were formerly carried in a palanquin. But on one occasion when a wedding procession came to a river, everybody began to catch fish, leaving the bride deserted, and the palanquin-bearers, seeing this, carried her off. To prevent the recurrence of such a mischance the couple now have to walk. Widow-marriage is permitted, and the widow usually marries her late husband’s younger brother. Divorce is only permitted for misconduct on the part of the wife.

3. Religious beliefs.

The Dhuris principally worship the goddess Devi. Nearly all members of the caste belong to the Kabīrpanthi sect. They believe that the sun on setting goes through the earth, and that the milky way is the path by which the elephant of the heavens passes from south to north to feed on the young bamboo shoots, of which he is very fond. They think that the constellation of the Great Bear is a cot with three thieves tied to it. The thieves came to steal the cot, which belonged to an old woman, but God caught them and tied them down there for ever. Orion is the plough left by one of the Pāndava brothers after he had finished tilling the heavens. The dead are burnt. They observe mourning during nine or ten days for an adult and make libations to the dead at the usual period in the month of Kunwār (September-October).

4. Occupation and social status.

The proper occupation of the caste is to parch rice. The rice is husked and then parched in an earthen pan, and subsequently bruised with a mallet in a wooden mortar. When prepared in this manner it is called cheora. The Dhuris also act as khidmatgārs or household servants, but the members of the Badharia subcaste refuse to do this work. Some members of the caste are fishermen, and others grow melons and sweet potatoes. Considering that they live in Chhattīsgarh, the caste are somewhat scrupulous in the matter of food, neither eating fowls nor drinking liquor. The Kawardha Dhuris, however, who are later immigrants than the others, do not observe these restrictions, the reason for which may be that the Dhuris think it necessary to be strict in the matter of food, so that no one may object to take parched rice from them. Rāwats and Gonds take food from their hands in some places, and their social status in Chhattīsgarh is about equivalent to that of the Rāwats or Ahīrs. A man of the caste who kills a cow or gets vermin in a wound must go to Amārkantak to bathe in the Nerbudda.

Dumāl

1. Origin and traditions.

Dumāl. 562—An agricultural caste found in the Uriya country and principally in the Sonpur State, recently transferred to Bihār and Orissa. In 1901, 41,000 Dumāls were enumerated in the Central Provinces, but only a few persons now remain. The caste originally came from Orissa. They themselves say that they were formerly a branch of the Gaurs, with whom they now have no special connection. They derive their name from a village called Dumba Hadap in the Athmālik State, where they say that they lived. Another story is that Dumāl is derived from Duma, the name of a gateway in Baud town, near which they dwelt. Sir H. Risley says: “The Dumāls or Jādupuria Gaura seem to be a group of local formation. They cherish the tradition that their ancestors came to Orissa from Jādupur, but this appears to be nothing more than the name of the Jādavas or Yādavas, the mythical progenitors of the Goala caste transformed into the name of an imaginary town.”

2. Subdivisions.

The Dumāls have no subcastes, but they have a complicated system of exogamy. This includes three kinds of divisions or sections, the got or sept, the barga or family title and the mitti or earth from which they sprang, that is, the name of the original village of the clan. Marriage is prohibited only between persons who have the same got, barga and mitti; if any one of these is different it is allowed. Thus a man of the Nāg got, Padhān barga and Hindolsai mitti may marry a girl of the Nāg got, Padhān barga and Kandhpadā mitti; or one of the Nāg got, Karmi barga and Hindolsai mitti; or one of the Bud got, Padhān barga and Hindolsai mitti. The bargas are very numerous, but the gots and mittis are few and common to many bargas; and many people have forgotten the name of their mitti altogether. Marriage therefore usually depends on the bargas being different. The following table shows the got, barga and mitti of a few families:

The only other gots besides those given above are Kachhap (tortoise), Ulūk (owl) and Limb (nim-tree). The gots are thus totemistic, and the animal or plant giving its name to the got is venerated and worshipped. The names of bargas are diverse. Some are titles indicating the position of the founder of the family in life, as Nāik (leader), Padhān (chief), Karmi (manager), Mahākul (great family) and so on. Others are derived from functions performed in sacrifices, as Amāyat (one who kills the animal in the sacrifice), Gurandi (one who makes a preparation of sugar for it), Dehri (priest), Bārik (one who carries the god’s umbrella), Kamp (one who is in charge of the baskets containing the sacred articles of the temple). Another set of bargas are names signifying the performance of menial functions in household service, as Gejo (kitchen-cleaner), Chaulia (rice-cleaner), Gadua (lotā-bearer), Dāng (spoon-bearer), Ghusri (cleaner of the dining-place with cowdung). Other names of bargas are derived from the caste’s traditional occupation of grazing cattle, as Mesua or Mendli (shepherd), Gaigariya (milkman), Chhānd (one who ties a rope to the legs of a cow when milking her). These names are interesting as showing that the Dumāls before taking to their present occupation of agriculture were temple servants, household menials and cattle-herds, thus fulfilling the functions now performed by the Rāwat or Gaur caste of graziers in Sambalpur. The names of the mittis or villages show that their original home was in the Orissa Tributary Mahāls, while the totemistic names of gots indicate their Dravidian origin. The marriage of first cousins is prohibited.

3. Marriage.

Girls must be married before adolescence, and in the event of the parents failing to accomplish this, the following heavy penalty is imposed on the girl herself. She is taken to the forest and tied to a tree with thread, this proceeding signifying her permanent exclusion from the caste. Any one belonging to another caste can then take her away and marry her if he chooses to do so. In practice, however, this penalty is very rarely imposed, as the parents can get out of it by marrying her to an old man, whether he is already married or not, the parents bearing all the expenses, while the husband gives two to four annas as a nominal contribution. After the marriage the old man can either keep the girl as his wife or divorce her for a further nominal payment of eight annas to a rupee. She then becomes a widow and can marry again, while her parents will get ten or twenty rupees for her.

The boy’s father makes the proposal for the marriage according to the following curious formula. Taking some fried grain he goes to the house of the father of the bride and addresses him as follows in the presence of the neighbours and the relatives of both parties: “I hear that the tree has budded and a blossom has come out; I intend to pluck it.” To which the girl’s father replies: “The flower is delicate; it is in the midst of an ocean and very difficult to approach: how will you pluck it?” To which the reply is: ‘I shall bring ships and dongas (boats) and ply them in the ocean and fetch the flower.’ And again: “If you do pluck it, can you support it? Many difficulties may stand in the way, and the flower may wither or get lost; will it be possible for you to steer the flower’s boat in the ocean of time, as long as it is destined to be in this world?” To which the answer is: ‘Yes, I shall, and it is with that intention that I have come to you.’ On which the girl’s father finally says: ‘Very well then, I have given you the flower.’ The question of the bride’s price is then discussed. There are three recognised scales—Rs. 7 and 7 pieces of cloth, Rs. 9 and 9 pieces of cloth, and Rs. 18 and 18 pieces of cloth. The rupees in question are those of Orissa, and each of them is worth only two-thirds of a Government rupee. In cases of extreme poverty Rs. 2 and 2 pieces of cloth are accepted. The price being fixed, the boy’s father goes to pay it after an interval; and on this occasion he holds out his cloth, and a cocoanut is placed on it and broken by the girl’s father, which confirms the betrothal. Before the marriage seven married girls go out and dig earth after worshipping the ground, and on their return let it all fall on to the head of the bridegroom’s mother, which is protected only by a cloth. On the next day offerings are made to the ancestors, who are invited to attend the ceremony as village gods. The bridegroom is shaved clean and bathed, and the Brāhman then ties an iron ring to his wrist, and the barber puts the turban and marriage-crown on his head. The procession then starts, but any barber who meets it on the way may put a fresh marriage-crown on the bridegroom’s head and receive eight annas or a rupee for it, so that he sometimes arrives at his destination wearing four or five of them. The usual ceremonies attend the arrival. At the marriage the couple are blindfolded and seated in the shed, while the Brāhman priest repeats mantras or verses, and during this time the parents and the parties must continue placing nuts and pice all over the shed. These are the perquisites of the Brāhman. The hands of the couple are then tied together with kusha grass (Eragrostis cynosuroides), and water is poured over them. After the ceremony the couple gamble with seven cowries and seven pieces of turmeric. The boy then presses a cowrie on the ground with his little finger, and the girl has to take it away, which she easily does. The girl in her turn holds a cowrie inside her clenched hand, and the boy has to remove it with his little finger, which he finds it impossible to do. Thus the boy always loses and has to promise the girl something, either to give her an ornament or to take her on a pilgrimage, or to make her the mistress of his house. On the fifth or last day of the ceremony some curds are placed in a small pot, and the couple are made to churn them; this is probably symbolical of the caste’s original occupation of tending cattle. The bride goes to her husband’s house for three days, and then returns home. When she is to be finally brought to her husband’s house, his father with some relatives goes to the parents of the girl and asks for her. It is now strict etiquette for her father to refuse to send her on the first occasion, and they usually have to call on him three or four times at intervals of some days, and selecting the days given by the astrologer as auspicious. Occasionally they have to go as many as ten times; but finally, if the girl’s father proves very troublesome, they send an old woman who drags away the girl by force. If the father sends her away willingly he gives her presents of several basket-loads of grain, oil, turmeric, cooking-pots, cloth, and if he is well off a cow and bullocks, the value of the presents amounting to about Rs. 50. The girl’s brother takes her to her husband’s house, where a repetition of the marriage ceremony on a small scale is performed. Twice again after the consummation of the marriage she visits her parents for periods of one and six months, but after this she never again goes to their house unaccompanied by her husband. Widow-marriage is allowed, and the widow may marry the younger brother of her late husband or not as she pleases. But if she marries another man he must pay a sum of Rs. 10 to Rs. 20 for her, of which Rs. 5 go to the Panua or headman of the caste, and Rs. 2 to their tutelary goddess Parmeshwari. The children by the first husband are kept either by his relatives or the widow’s parents, and do not go to the new husband. When a bachelor marries a widow, he is first married to a flower or sahara tree. A widow who has remarried cannot take part in any worship or marriage ceremony in her house, not even in the marriage of her own sons. Divorce is allowed, and is effected in the presence of the caste panchāyat or committee. A divorced woman may marry again.

4. Religious and social customs.

The caste worship the goddess Parmeshwari, the wife of Vishnu, and Jagannāth, the Uriya incarnation of Vishnu. Parmeshwari is worshipped by Brāhmans, who offer bread and khīr or rice and milk to her; goats are also offered by the Dehri or Mahākul, the caste priest, who receives the heads of the goats as his remuneration. They believe in witches, who they think drink the blood of children, and employ sorcerers to exorcise them. They worship a stick on Dasahra day in remembrance of their old profession of herding cattle, and they worship cows and buffaloes at the full moon of Shrāwan (July-August). During Kunwār, on the eighth day of each fortnight, two festivals are held. At the first each girl in the family wears a thread containing eighteen knots twisted three times round her neck. All the girls fast and receive presents of cloths and grain from their brothers. This is called Bhaijiuntia, or the ceremony for the welfare of the brothers. On the second day the mother of the family does the same, and receives presents from her sons, this being Puājiuntia, or the ceremony for the welfare of sons. The Dumāls believe that in the beginning water covered the earth. They think that the sun and moon are the eyes of God, and that the stars are the souls of virtuous men, who enjoy felicity in heaven for the period measured by the sum of their virtuous actions, and when this has expired have to descend again to earth to suffer the agonies of human life. When a shooting star is seen they think it is the soul of one of these descending to be born again on earth. They both burn and bury their dead according to their means. After a body is buried they make a fire over the grave and place an empty pot on it. Mourning is observed for twelve days in the case of a married and for seven in the case of an unmarried person. Children dying when less than six days old are not mourned at all. During mourning the persons of the household do not cook for themselves. On the third day after the death three leaf-plates, each containing a little rice, sugar and butter, are offered to the spirit of the deceased. On the fourth day four such plates are offered, and on the fifth day five, and so on up to the ninth day when the Pindas or sacrificial cakes are offered, and nine persons belonging to the caste are invited, food and a new piece of cloth being given to each. Should only one attend, nine plates of food would be served to him, and he would be given nine pieces of cloth. If two or more persons in a family are killed by a tiger, a Sulia or magician is called in, and he pretends to be the tiger and to bite some one in the family, who is then carried as a corpse to the burial-place, buried for a short time and taken out again. All the ceremonies of mourning are observed for him for one day. This proceeding is believed to secure immunity for the family from further attacks. In return for his services the Sulia gets a share of everything in the house corresponding to what he would receive, supposing he were a member of the family, on a partition. Thus if the family consisted of only two persons he would get a third part of the whole property.

The Dumāls eat meat, including wild boar’s flesh, but not beef, fowls or tame pigs. They do not drink liquor. They will take food cooked with water from Brāhmans and Sudhs, and even the leavings of food from Brāhmans. This is probably because they were formerly the household servants of Brāhmans, though they have now risen somewhat in position and rank, together with the Koltas and Sudhs, as a good cultivating caste. Their women and girls can easily be distinguished, the girls because the hair is shaved until they are married, and the women because they wear bangles of glass on one arm and of lac on the other. They never wear nose-rings or the ornament called pairi on the feet, and no ornaments are worn on the arm above the elbow. They do not wear black clothing. The women are tattooed on the hands, feet and breast. Morality within the caste is lax. A woman going wrong with a man of her own caste is not punished, because the Dumāls live generally in Native States, where it is the business of the Rāja to find the seducer. But she is permanently excommunicated for a liaison with a man of another caste. Eating with a very low caste is almost the only offence which entails permanent exclusion for both sexes. The Dumāls have a bad reputation for fidelity, according to a saying: ‘You cannot call the jungle a plain, and you should not call the Dumāl a brother,’ that is, do not trust a Dumāl. Like the Ahīrs they are somewhat stupid, and when enquiry was being made from them as to what crops they did not grow, one of them replied that they did not sow salt. They are good cultivators, and will grow anything except hemp and turmeric. In some places they still follow their traditional occupation of grazing cattle.

Fakīr

1. General notice.

Fakīr. 563—The class of Muhammadan beggars. In the Central Provinces the name is practically confined to Muhammadans, but in Upper India Hindus also use it. Nearly 9000 Fakīrs were returned in 1911, being residents mainly of Districts with large towns, as Jubbulpore, Nāgpur and Amraoti. Nearly two-fifths of the Muhammadans of the Central Provinces live in towns, and Muhammadan beggars would naturally congregate there also. The name is derived from the Arabic fakr, poverty. The Fakīrs are often known as Shāh, Lord, or Sain, a corruption of the Sanskrit Swāmi, master. Muhammad did not recognise religious ascetism, and expressly discouraged it. But even during his lifetime his companions Abu Bakr and Ali established religious orders with Zikrs or special exercises, and all Muhammadan Fakīrs trace their origin to Abu Bakr or Ali subsequently the first and fourth Caliphs.564 The Fakīrs are divided into two classes, the Ba Shara or those who live according to the rules of Islam and marry; and the Be Shara or those without the law. These latter have no wives or homes; they drink intoxicating liquor, and neither fast, pray nor rule their passions. But several of the orders contain both married and celibate groups.

2. Principal orders.

The principal classes of Fakīrs in the Central Provinces are the Madari, Gurujwāle or Rafai, Jalāli, Mewāti, Sada Sohāgal and Nakshbandia. All of these except the Nakshbandia are nominally at least Be Shara, or without the law, and celibate.

The Madari are the followers of one Madar Shāh, a converted Jew of Aleppo, whose tomb is supposed to be at Makhanpur in the United Provinces. Their characteristic badge is a pair of pincers. Some, in order to force people to give them alms, go about dragging a chain or lashing their legs with a whip. Others are monkey- and bear-trainers and rope-dancers. The Madaris are said to be proof against snakes and scorpions, and to have power to cure their bites. They will leap into a fire and trample it down, crying out, ‘Aam Madar, Aam Madar.’565

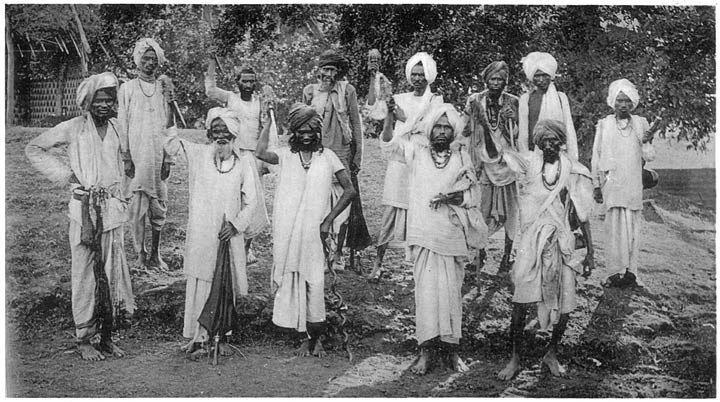

Group of Gurujwāle Fakīrs.

The Gurujwāle or Rafai have as their badge a spiked iron club with small chains attached to the end. The Fakīr rattles the chains of his club to announce his presence, and if the people will not give him alms strikes at his own cheek or eye with the sharp point of his club, making the blood flow. They make prayers to their club once a year, so that it may not cause them serious injury when they strike themselves with it.

The Jalālias are named after their founder, Jalāl-ud-dīn of Bokhāra, and have a horse-whip as their badge, with which they sometimes strike themselves on the hands and feet. They are said to consume large quantities of bhāng, and to eat snakes and scorpions; they shave all the hair on the head and face, including the eyebrows, except a small scalp-lock on the right side.

The Mewāti appear to be a thieving order. They are also known as Kulchor or thieves of the family, and appear to have been originally a branch of the Madari, who were perhaps expelled on account of their thieving habits. Their distinguishing mark is a double bag like a pack-saddle, which they hang over their shoulders. The Sada or Mūsa Sohāg are an order who dress like women, put on glass bangles, have their ears and noses pierced for ornaments, and wear long hair, but retain their beards and moustaches. They regard themselves as brides of God or of Hussan, and beg in this guise.

The Nakshbandia are the disciples of Khwaja Mīr Muhammad, who was called Nakshband or brocade-maker. They beg at night-time, carrying an open brass lamp with a short wick. Children are fond of the Nakshband, and go out in numbers to give him money. In return he marks them on the brow with oil from his lamp. They are quiet and well behaved, belonging to the Ba Shara class of Fakīrs, and having homes and families.

The Kalandaria or wandering dervishes, who are occasionally met with, were founded by Kalandar Yusuf-ul-Andalusi, a native of Spain. Having been dismissed from another order, he founded this as a new one, with the obligation of perpetual travelling. The Kalandar is a well-known figure in Eastern stories.566

The Maulawiyah are the well-known dancing dervishes of Constantinople and Cairo, but do not belong to India.

The different orders of Fakīrs are not strictly endogamous, and marriages can take place between their members, though the Madaris prefer to confine marriage to their own order. Fakīrs as a body are believed to marry among themselves, and hence to form something in the nature of a caste, but they freely admit outsiders, whether Muhammadans or proselytised Hindus.

3. Rules and customs.

Every Fakīr must have a Murshid or preceptor, and be initiated by him. This applies also to boys born in the order, and a father cannot initiate his son. The rite is usually simple, the novice having to drink sherbet from the same cup as his preceptor and make him a present of Rs. 1–4; but some orders insist that the whole body of a novice should be shaved clean of hair before he is initiated. The principal religious exercise of Fakīrs is known as Zikr, and consists in the continual repetition of the names of God by various methods, it being supposed that they can draw the name from different parts of the body. The exercise is so exhausting that they frequently faint under it, and is varied by repetition of certain chapters of the Korān. The Fakīr has a tasbīh or rosary, often consisting of ninety-nine beads, on which he repeats the ninety-nine names of God. The Fakīrs beg both from Hindus and Muhammadans, and are sometimes troublesome and importunate, inflicting wounds on themselves as a means of extorting alms. One beggar in Saugor said that he would give every one who gave him alms five strokes with his whip, and attracted considerable custom by this novel expedient. Some of them are in charge of Muhammadan cemeteries and receive fees for a burial, while others live at the tombs of saints. They keep the tomb in good repair, cover it with a green cloth and keep a lighted lamp on it, and appropriate the offerings made by visitors. Owing to their solitude and continuous repetition of prayers many Fakīrs fall into a distraught condition, when they are known as mast, and are believed to be possessed of a spirit. At such a time the people attach the greatest importance to any utterances which fall from the Fakīr’s lips, believing that he has the gift of prophecy, and follow him about with presents to induce him to make some utterance.