полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

Mr. Cumberlege224 notes that in former times all Chāran Banjāras when carrying grain for an army placed a twig of some tree, the sacred nīm225 when available, in their turban to show that they were on the war-path; and that they would do the same now if they had occasion to fight to the death on any social matter or under any supposed grievance.

19. Social customs.

The Banjāras eat all kinds of meat, including fowls and pork, and drink liquor. But the Mathurias abstain from both flesh and liquor. Major Gunthorpe states that the Banjāras are accustomed to drink before setting out for a dacoity or robbery and, as they smoke after drinking, the remains of leaf-pipes lying about the scene of action may indicate their handiwork. They rank below the cultivating castes, and Brāhmans will not take water to drink from them. When engaged in the carrying trade, they usually lived in kuris or hamlets attached to such regular villages as had considerable tracts of waste land belonging to them. When the tānda or caravan started on its long carrying trips, the young men and some of the women went with it with the working bullocks, while the old men and the remainder of the women and children remained to tend the breeding cattle in the hamlet. In Nimār they generally rented a little land in the village to give them a footing, and paid also a carrying fee on the number of cattle present. Their spare time was constantly occupied in the manufacture of hempen twine and sacking, which was much superior to that obtainable in towns. Even in Captain Forsyth’s226 time (1866) the construction of railways and roads had seriously interfered with the Banjaras’ calling, and they had perforce taken to agriculture. Many of them have settled in the new ryotwāri villages in Nimār as Government tenants. They still grow tilli227 in preference to other crops, because this oilseed can be raised without much labour or skill, and during their former nomadic life they were accustomed to sow it on any poor strip of land which they might rent for a season. Some of them also are accustomed to leave a part of their holding untilled in memory of their former and more prosperous life. In many villages they have not yet built proper houses, but continue to live in mud huts thatched with grass. They consider it unlucky to inhabit a house with a cement or tiled roof; this being no doubt a superstition arising from their camp life. Their houses must also be built so that the main beams do not cross, that is, the main beam of a house must never be in such a position that if projected it would cut another main beam; but the beams may be parallel. The same rule probably governed the arrangement of tents in their camps. In Nimār they prefer to live at some distance from water, probably that is of a tank or river; and this seems to be a survival of a usage mentioned by the Abbé Dubois:228 “Among other curious customs of this odious caste is one that obliges them to drink no water which is not drawn from springs or wells. The water from rivers and tanks being thus forbidden, they are obliged in case of necessity to dig a little hole by the side of a tank or river and take the water filtering through, which, by this means, is supposed to become spring water.” It is possible that this rule may have had its origin in a sanitary precaution. Colonel Sleeman notes229 that the Banjāras on their carrying trips preferred by-paths through jungles to the high roads along cultivated plains, as grass, wood and water were more abundant along such paths; and when they could not avoid the high roads, they commonly encamped as far as they could from villages and towns, and upon the banks of rivers and streams, with the same object of obtaining a sufficient supply of grass, wood and water. Now it is well known that the decaying vegetation in these hill streams renders the water noxious and highly productive of malaria. And it seems possible that the perception of this fact led the Banjāras to dig shallow wells by the sides of the streams for their drinking-water, so that the supply thus obtained might be in some degree filtered by percolation through the intervening soil and freed from its vegetable germs. And the custom may have grown into a taboo, its underlying reason being unknown to the bulk of them, and be still practised, though no longer necessary when they do not travel. If this explanation be correct it would be an interesting conclusion that the Banjāras anticipated so far as they were able the sanitary precaution by which our soldiers are supplied with portable filters when on the march.

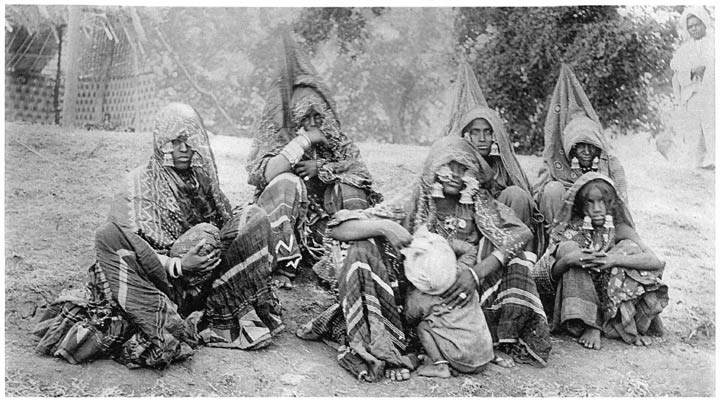

Group of Banjāra women.

20. The Nāik or headman. Banjāra dogs.

Each kuri (hamlet) or tānda (caravan) had a chief or leader with the designation of Nāik, a Telugu word meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master.’ The office of Nāik230 was only partly hereditary, and the choice also depended on ability. The Nāik had authority to decide all disputes in the community, and the only appeal from him lay to the representatives of Bhangi and Jhangi Nāik’s families at Narsi and Poona, and to Burthia Nāik’s successors in the Telugu country. As already seen, the Nāik received two shares if he participated in a robbery or other crime, and a fee on the remarriage of a widow outside her family and on the discovery of a witch. Another matter in which he was specially interested was pig-sticking. The Banjāras have a particular breed of dogs, and with these they were accustomed to hunt wild pig on foot, carrying spears. When a pig was killed, the head was cut off and presented to the Nāik or headman, and if any man was injured or gored by the pig in the hunt, the Nāik kept and fed him without charge until he recovered.

The following notice of the Banjāras and their dogs may be reproduced:231 “They are brave and have the reputation of great independence, which I am not disposed to allow to them. The Wanjāri indeed is insolent on the road, and will drive his bullocks up against a Sahib or any one else; but at any disadvantage he is abject enough. I remember one who rather enjoyed seeing his dogs attack me, whom he supposed alone and unarmed, but the sight of a cocked pistol made him very quick in calling them off, and very humble in praying for their lives, which I spared less for his entreaties than because they were really noble animals. The Wanjāris are famous for their dogs, of which there are three breeds. The first is a large, smooth dog, generally black, sometimes fawn-coloured, with a square heavy head, most resembling the Danish boarhound. This is the true Wanjāri dog. The second is also a large, square-headed dog, but shaggy, more like a great underbred spaniel than anything else. The third is an almost tailless greyhound, of the type known all over India by the various names of Lāt, Polygar, Rāmpūri, etc. They all run both by sight and scent, and with their help the Wanjāris kill a good deal of game, chiefly pigs; but I think they usually keep clear of the old fighting boars. Besides sport and their legitimate occupations the Wanjāris seldom stickle at supplementing their resources by theft, especially of cattle; and they are more than suspected of infanticide.”

The Banjāras are credited with great affection for their dogs, and the following legend is told about one of them: Once upon a time a Banjāra, who had a faithful dog, took a loan from a Bania (moneylender) and pledged his dog with him as security for payment. And some time afterwards, while the dog was with the moneylender, a theft was committed in his house, and the dog followed the thieves and saw them throw the property into a tank. When they went away the dog brought the Bania to the tank and he found his property. He was therefore very pleased with the dog and wrote a letter to his master, saying that the loan was repaid, and tied it round his neck and said to him, ‘Now, go back to your master.’ So the dog started back, but on his way he met his master, the Banjāra, coming to the Bania with the money for the repayment of the loan. And when the Banjāra saw the dog he was angry with him, not seeing the letter, and thinking he had run away, and said to him, ‘Why did you come, betraying your trust?’ and he killed the dog in a rage. And after killing him he found the letter and was very grieved, so he built a temple to the dog’s memory, which is called the Kukurra Mandhi. And in the temple is the image of a dog. This temple is in the Drūg District, five miles from Bālod. A similar story is told of the temple of Kukurra Math in Mandla.

21. Criminal tendencies of the caste.

The following notice of Banjāra criminals is abstracted from Major Gunthorpe’s interesting account:232 “In the palmy days of the tribe dacoities were undertaken on the most extensive scale. Gangs of fifty to a hundred and fifty well-armed men would go long distances from their tāndas or encampments for the purpose of attacking houses in villages, or treasure-parties or wealthy travellers on the high roads. The more intimate knowledge which the police have obtained concerning the habits of this race, and the detection and punishment of many criminals through approvers, have aided in stopping the heavy class of dacoities formerly prevalent, and their operations are now on a much smaller scale. In British territory arms are scarcely carried, but each man has a good stout stick (gedi), the bark of which is peeled off so as to make it look whitish and fresh. The attack is generally commenced by stone-throwing and then a rush is made, the sticks being freely used and the victims almost invariably struck about the head or face. While plundering, Hindustāni is sometimes spoken, but as a rule they never utter a word, but grunt signals to one another. Their loin-cloths are braced up, nothing is worn on the upper part of the body, and their faces are generally muffled. In house dacoities men are posted at different corners of streets, each with a supply of well-chosen round stones to keep off any people coming to the rescue. Banjāras are very expert cattle-lifters, sometimes taking as many as a hundred head or even more at a time. This kind of robbery is usually practised in hilly or forest country where the cattle are sent to graze. Secreting themselves they watch for the herdsman to have his usual midday doze and for the cattle to stray to a little distance. As many as possible are then driven off to a great distance and secreted in ravines and woods. If questioned they answer that the animals belong to landowners and have been given into their charge to graze, and as this is done every day the questioner thinks nothing more of it. After a time the cattle are quietly sold to individual purchasers or taken to markets at a distance.”

22. Their virtues.

The Banjāras, however, are far from being wholly criminal, and the number who have adopted an honest mode of livelihood is continually on the increase. Some allowance must be made for their having been deprived of their former calling by the cessation of the continual wars which distracted India under native rule, and the extension of roads and railways which has rendered their mode of transport by pack-bullocks almost entirely obsolete. At one time practically all the grain exported from Chhattīsgarh was carried by them. In 1881 Mr. Kitts noted that the number of Banjāras convicted in the Berār criminal courts was lower in proportion to the strength of the caste than that of Muhammadans, Brāhmans, Koshtis or Sunars,233 though the offences committed by them were usually more heinous. Colonel Mackenzie had quite a favourable opinion of them: “A Banjāra who can read and write is unknown. But their memories, from cultivation, are marvellous and very retentive. They carry in their heads, without slip or mistake, the most varied and complicated transactions and the share of each in such, striking a debtor and creditor account as accurately as the best-kept ledger, while their history and songs are all learnt by heart and transmitted orally from generation to generation. On the whole, and taken rightly in their clannish nature, their virtues preponderate over their vices. In the main they are truthful and very brave, be it in war or the chase, and once gained over are faithful and devoted adherents. With the pride of high descent and with the right that might gives in unsettled and troublous times, these Banjāras habitually lord it over and contemn the settled inhabitants of the plains. And now not having foreseen their own fate, or at least not timely having read the warnings given by a yearly diminishing occupation, which slowly has taken their bread away, it is a bitter pill for them to sink into the ryot class or, oftener still, under stern necessity to become the ryot’s servant. But they are settling to their fate, and the time must come when all their peculiar distinctive marks and traditions will be forgotten.”

Barai

1. Origin and traditions.

Barai, 234 Tamboli, Pansāri.—The caste of growers and sellers of the betel-vine leaf. The three terms are used indifferently for the caste in the Central Provinces, although some shades of variation in the meaning can be detected even here—Barai signifying especially one who grows the betel-vine, and Tamboli the seller of the prepared leaf; while Pansāri, though its etymological meaning is also a dealer in pān or betel-vine leaves, is used rather in the general sense of a druggist or grocer, and is apparently applied to the Barai caste because its members commonly follow this occupation. In Bengal, however, Barai and Tamboli are distinct castes, the occupations of growing and selling the betel-leaf being there separately practised. And they have been shown as different castes in the India Census Tables of 1901, though it is perhaps doubtful whether the distinction holds good in northern India.235 In the Central Provinces and Berār the Barais numbered nearly 60,000 persons in 1911. They reside principally in the Amraoti, Buldāna, Nāgpur, Wardha, Saugor and Jubbulpore Districts. The betel-vine is grown principally in the northern Districts of Saugor, Damoh and Jubbulpore and in those of Berār and the Nāgpur plain. It is noticeable also that the growers and sellers of the betel-vine numbered only 14,000 in 1911 out of 33,000 actual workers of the Barai caste; so that the majority of them are now employed in ordinary agriculture, field-labour and other avocations. No very probable derivation has been obtained for the word Barai, unless it comes from bāri, a hedge or enclosure, and simply means ‘gardener.’ Another derivation is from barāna, to avert hailstorms, a calling which they still practise in northern India. Pān, from the Sanskrit parna (leaf), is the leaf par excellence. Owing to the fact that they produce what is perhaps the most esteemed luxury in the diet of the higher classes of native society, the Barais occupy a fairly good social position, and one legend gives them a Brāhman ancestry. This is to the effect that the first Barai was a Brāhman whom God detected in a flagrant case of lying to his brother. His sacred thread was confiscated and being planted in the ground grew up into the first betel-vine, which he was set to tend. Another story of the origin of the vine is given later in this article. In the Central Provinces its cultivation has probably only flourished to any appreciable extent for a period of about three centuries, and the Barai caste would appear to be mainly a functional one, made up of a number of immigrants from northern India and of recruits from different classes of the population, including a large proportion of the non-Aryan element.

2. Caste subdivisions.

The following endogamous divisions of the caste have been reported: Chaurāsia, so called from the Chaurāsi pargana of the Mīrzāpur District; Panagaria from Panāgar in Jubbulpore; Mahobia from Mahoba in Hamīrpur; Jaiswār from the town of Jais in the Rai Bareli District of the United Provinces; Gangapāri, coming from the further side of the Ganges; and Pardeshi or Deshwāri, foreigners. The above divisions all have territorial names, and these show that a large proportion of the caste have come from northern India, the different batches of immigrants forming separate endogamous groups on their arrival here. Other subcastes are the Dūdh Barais, from dūdh, milk; the Kumān, said to be Kunbis who have adopted this occupation and become Barais; the Jharia and Kosaria, the oldest or jungly Barais, and those who live in Chhattīsgarh; the Purānia or old Barais; the Kumhārdhang, who are said to be the descendants of a potter on whose wheel a betel-vine grew; and the Lahuri Sen, who are a subcaste formed of the descendants of irregular unions. None of the other subcastes will take food from these last, and the name is locally derived from lahuri, lower, and sen or shreni, class. The caste is also divided into a large number of exogamous groups or septs which may be classified according to their names as territorial, titular and totemistic. Examples of territorial names are: Kanaujia of Kanauj, Burhānpuria of Burhānpur, Chitoria of Chitor in Rājputāna, Deobijha the name of a village in Chhattīsgarh, and Kharondiha from Kharond or Kālāhandi State. These names must apparently have been adopted at random when a family either settled in one of these places or removed from it to another part of the country. Examples of titular names of groups are: Pandit (priest), Bhandāri (store-keeper), Patharha (hail-averter), Batkāphor (pot-breaker), Bhulya (the forgetful one), Gūjar (a caste), Gahoi (a caste), and so on. While the following are totemistic groups: Katāra (dagger), Kulha (jackal), Bandrele (monkey), Chīkhalkār (from chīkhal, mud), Richharia (bear), and others. Where the group is named after another caste it probably indicates that a man of that caste became a Barai and founded a family; while the fact that some groups are totemistic shows that a section of the caste is recruited from the indigenous tribes. The large variety of names discloses the diverse elements of which the caste is made up.

3. Marriage

Marriage within the gotra or exogamous group and within three degrees of relationship between persons connected through females is prohibited. Girls are usually wedded before adolescence, but no stigma attaches to the family if they remain single beyond this period. If a girl is seduced by a man of the caste she is married to him by the pāt, a simple ceremony used for widows. In the southern Districts a barber cuts off a lock of her hair on the banks of a tank or river by way of penalty, and a fast is also imposed on her, while the caste-fellows exact a meal from her family. If she has an illegitimate child, it is given away to somebody else, if possible. A girl going wrong with an outsider is expelled from the caste.

Polygamy is permitted and no stigma attaches to the taking of a second wife, though it is rarely done except for special family reasons. Among the Marātha Barais the bride and bridegroom must walk five times round the marriage altar and then worship the stone slab and roller used for pounding spices. This seems to show that the trade of the Pansāri or druggist is recognised as being a proper avocation of the Barai. They subsequently have to worship the potter’s wheel. After the wedding the bride, if she is a child, goes as usual to her husband’s house for a few days. In Chhattīsgarh she is accompanied by a few relations, the party being known as Chauthia, and during her stay in her husband’s house the bride is made to sleep on the ground. Widow marriage is permitted, and the ceremony is conducted according to the usage of the locality. In Betūl the relatives of the widow take the second husband before Māroti’s shrine, where he offers a nut and some betel-leaf. He is then taken to the mālguzār’s house and presents to him Rs. 1–4–0, a cocoanut and some betel-vine leaf as the price of his assent to the marriage. If there is a Deshmukh236 of the village, a cocoanut and betel-leaf are also given to him. The nut offered to Māroti represents the deceased husband’s spirit, and is subsequently placed on a plank and kicked off by the new bridegroom in token of his usurping the other’s place, and finally buried to lay the spirit. The property of the first husband descends to his children, and failing them his brother’s children or collateral heirs take it before the widow. A bachelor espousing a widow must first go through the ceremony of marriage with a swallow-wort plant. When a widower marries a girl a silver impression representing the deceased first wife is made and worshipped daily with the family gods. Divorce is permitted on sufficient grounds at the instance of either party, being effected before the caste committee or panchāyat. If a husband divorces his wife merely on account of bad temper, he must maintain her so long as she remains unmarried and continues to lead a moral life.

4. Religion and social status.

The Barais especially venerate the Nāg or cobra and observe the festival of Nāg-Panchmi (Cobra’s fifth), in connection with which the following story is related. Formerly there was no betel-vine on the earth. But when the five Pāndava brothers celebrated the great horse sacrifice after their victory at Hastinapur, they wanted some, and so messengers were sent down below the earth to the residence of the queen of the serpents, in order to try and obtain it. Bāsuki, the queen of the serpents, obligingly cut off the top joint of her little finger and gave it to the messengers. This was brought up and sown on the earth, and pān creepers grew out of the joint. For this reason the betel-vine has no blossoms or seeds, but the joints of the creepers are cut off and sown, when they sprout afresh; and the betel-vine is called Nāgbel or the serpent-creeper. On the day of Nāg-Panchmi the Barais go to the bareja with flowers, cocoanuts and other offerings, and worship a stone which is placed in it and which represents the Nāg or cobra. A goat or sheep is sacrificed and they return home, no leaf of the pān garden being touched on that day. A cup of milk is also left, in the belief that a cobra will come out of the pān garden and drink it. The Barais say that members of their caste are never bitten by cobras, though many of these snakes frequent the gardens on account of the moist coolness and shade which they afford. The Agarwāla Banias, from whom the Barais will take food cooked without water, have also a legend of descent from a Nāga or snake princess. ‘Our mother’s house is of the race of the snake,’ say the Agarwāls of Bihār.237 The caste usually burn the dead, with the exception of children and persons dying of leprosy or snake-bite, whose bodies are buried. Mourning is observed for ten days in the case of adults and for three days for children. In Chhattīsgarh if any portion of the corpse remains unburnt on the day following the cremation, the relatives are penalised to the extent of an extra feast to the caste-fellows. Children are named on the sixth or twelfth day after birth either by a Brāhman or by the women of the household. Two names are given, one for ceremonial and the other for ordinary use. When a Brāhman is engaged he gives seven names for a boy and five for a girl, and the parents select one out of these. The Barais do not admit outsiders into the caste, and employ Brāhmans for religious and ceremonial purposes. They are allowed to eat the flesh of clean animals, but very rarely do so, and they abstain from liquor. Brāhmans will take sweets and water from them, and they occupy a fairly good social position on account of the important nature of their occupation.

5. Occupation.

“It has been mentioned,” says Sir H. Risley,238 “that the garden is regarded as almost sacred, and the superstitious practices in vogue resemble those of the silk-worm breeder. The Bārui will not enter it until he has bathed and washed his clothes. Animals found inside are driven out, while women ceremonially unclean dare not enter within the gate. A Brāhman never sets foot inside, and old men have a prejudice against entering it. It has, however, been known to be used for assignations.” The betel-vine is the leaf of Piper betel L., the word being derived from the Malayalam vettila, ‘a plain leaf,’ and coming to us through the Portuguese betre and betle. The leaf is called pān, and is eaten with the nut of Areca catechu, called in Hindi supāri. The vine needs careful cultivation, the gardens having to be covered to keep off the heat of the sun, while liberal treatment with manure and irrigation is needed. The joints of the creepers are planted in February, and begin to supply leaves in about five months’ time. When the first creepers are stripped after a period of nearly a year, they are cut off and fresh ones appear, the plants being exhausted within a period of about two years after the first sowing. A garden may cover from half an acre to an acre of land, and belongs to a number of growers, who act in partnership, each owning so many lines of vines. The plain leaves are sold at from 2 annas to 4 annas a hundred, or a higher rate when they are out of season. Damoh, Rāmtek and Bilahri are three of the best-known centres of cultivation in the Central Provinces. The Bilahri leaf is described in the Ain-i-Akbari as follows: “The leaf called Bilahri is white and shining, and does not make the tongue harsh and hard. It tastes best of all kinds. After it has been taken away from the creeper, it turns white with some care after a month, or even after twenty days, when greater efforts are made.”239 For retail sale bīdas are prepared, consisting of a rolled betel-leaf containing areca-nut, catechu and lime, and fastened with a clove. Musk and cardamoms are sometimes added. Tobacco should be smoked after eating a bīda according to the saying, ‘Service without a patron, a young man without a shield, and betel without tobacco are alike savourless.’ Bīdas are sold at from two to four for a pice (farthing). Women of the caste often retail them, and as many are good-looking they secure more custom; they are also said to have an indifferent reputation. Early in the morning, when they open their shops, they burn some incense before the bamboo basket in which the leaves are kept, to propitiate Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth.