полная версия

полная версияThe Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 2

6. Marriage: betrothal.

At a betrothal in Nimār the bridegroom and his friends come and stay in the next village to that of the bride. The two parties meet on the boundary of the village, and here the bride-price is fixed, which is often a very large sum, ranging from Rs. 200 to Rs. 1000. Until the price is paid the father will not let the bridegroom into his house. In Yeotmāl, when a betrothal is to be made, the parties go to a liquor-shop and there a betel-leaf and a large handful of sugar are distributed to everybody. Here the price to be paid for the bride amounts to Rs. 40 and four young bullocks. Prior to the wedding the bridegroom goes and stays for a month or so in the house of the bride’s father, and during this time he must provide a supply of liquor daily for the bride’s male relatives. The period was formerly longer, but now extends to a month at the most. While he resides at the bride’s house the bridegroom wears a cloth over his head so that his face cannot be seen. Probably the prohibition against seeing him applies to the bride only, as the rule in Berār is that between the betrothal and marriage of a Chāran girl she may not eat or drink in the bridegroom’s house, or show her face to him or any of his relatives. Mathuria girls must be wedded before they are seven years old, but the Chārans permit them to remain single until after adolescence.

7. Marriage.

Banjāra marriages are frequently held in the rains, a season forbidden to other Hindus, but naturally the most convenient to them, because in the dry weather they are usually travelling. For the marriage ceremony they pitch a tent in lieu of the marriage-shed, and on the ground they place two rice-pounding pestles, round which the bride and bridegroom make the seven turns. Others substitute for the pestles a pack-saddle with two bags of grain in order to symbolise their camp life. During the turns the girl’s hand is held by the Joshi or village priest, or some other Brāhman, in case she should fall; such an occurrence being probably a very unlucky omen. Afterwards, the girl runs away and the Brāhman has to pursue and catch her. In Bhandāra the girl is clad only in a light skirt and breast-cloth, and her body is rubbed all over with oil in order to make his task more difficult. During this time the bride’s party pelt the Brāhman with rice, turmeric and areca-nuts, and sometimes even with stones; and if he is forced to cry with the pain, it is considered lucky. But if he finally catches the girl, he is conducted to a dais and sits there holding a brass plate in front of him, into which the bridegroom’s party drop presents. A case is mentioned of a Brāhman having obtained Rs. 70 in this manner. Among the Mathuria Banjāras of Berār the ceremony resembles the usual Hindu type.197 Before the wedding the families bring the branches of eight or ten different kinds of trees, and perform the hom or fire sacrifice with them. A Brāhman knots the clothes of the couple together, and they walk round the fire. When the bride arrives at the bridegroom’s hamlet after the wedding, two small brass vessels are given to her; she fetches water in these and returns them to the women of the boy’s family, who mix this with other water previously drawn, and the girl, who up to this period was considered of no caste at all, becomes a Mathuria.198 Food is cooked with this water, and the bride and bridegroom are formally received into the husband’s kuri or hamlet. It is possible that the mixing of the water may be a survival of the blood covenant, whereby a girl was received into her husband’s clan on her marriage by her blood being mixed with that of her husband.199 Or it may be simply symbolical of the union of the families. In some localities after the wedding the bride and bridegroom are made to stand on two bullocks, which are driven forward, and it is believed that whichever of them falls off first will be the first to die.

8. Widow remarriage.

Owing to the scarcity of women in the caste a widow is seldom allowed to go out of the family, and when her husband dies she is taken either by his elder or younger brother; this is in opposition to the usual Hindu practice, which forbids the marriage of a woman to her deceased husband’s elder brother, on the ground that as successor to the headship of the joint family he stands to her, at least potentially, in the light of a father. If the widow prefers another man and runs away to him, the first husband’s relatives claim compensation, and threaten, in the event of its being refused, to abduct a girl from this man’s family in exchange for the widow. But no case of abduction has occurred in recent years. In Berār the compensation claimed in the case of a woman marrying out of the family amounts to Rs. 75, with Rs. 5 for the Nāik or headman of the family. Should the widow elope without her brother-in-law’s consent, he chooses ten or twelve of his friends to go and sit dharna (starving themselves) before the hut of the man who has taken her. He is then bound to supply these men with food and liquor until he has paid the customary sum, when he may marry the widow.200 In the event of the second husband being too poor to pay monetary compensation, he gives a goat, which is cut into eighteen pieces and distributed to the community.201

9. Birth and death.

After the birth of a child the mother is unclean for five days, and lives apart in a separate hut, which is run up for her use in the kuri or hamlet. On the sixth day she washes the feet of all the children in the kuri, feeds them and then returns to her husband’s hut. When a child is born in a moving tānda or camp, the same rule is observed, and for five days the mother walks alone after the camp during the daily march. The caste bury the bodies of unmarried persons and those dying of smallpox and burn the others. Their rites of mourning are not strict, and are observed only for three days. The Banjāras have a saying: “Death in a foreign land is to be preferred, where there are no kinsfolk to mourn, and the corpse is a feast for birds and animals”; but this may perhaps be taken rather as an expression of philosophic resignation to the fate which must be in store for many of them, than a real preference, as with most people the desire to die at home almost amounts to an instinct.

10. Religion: Banjāri Devi.

One of the tutelary deities of the Banjāras is Banjāri Devi, whose shrine is usually located in the forest. It is often represented by a heap of stones, a large stone smeared with vermilion being placed on the top of the heap to represent the goddess. When a Banjāra passes the place he casts a stone upon the heap as a prayer to the goddess to protect him from the dangers of the forest. A similar practice of offering bells from the necks of cattle is recorded by Mr. Thurston:202 “It is related by Moor that he passed a tree on which were hanging several hundred bells. This was a superstitious sacrifice of the Banjāras (Lambāris), who, passing this tree, are in the habit of hanging a bell or bells upon it, which they take from the necks of their sick cattle, expecting to leave behind them the complaint also. Our servants particularly cautioned us against touching these diabolical bells, but as a few of them were taken for our own cattle, several accidents which happened were imputed to the anger of the deity to whom these offerings were made; who, they say, inflicts the same disorder on the unhappy bullock who carries a bell from the tree, as that from which he relieved the donor.” In their houses the Banjāri Devi is represented by a pack-saddle set on high in the room, and this is worshipped before the caravans set out on their annual tours.

11. Mīthu Bhūkia.

Another deity is Mīthu Bhūkia, an old freebooter, who lived in the Central Provinces; he is venerated by the dacoits as the most clever dacoit known in the annals of the caste, and a hut was usually set apart for him in each hamlet, a staff carrying a white flag being planted before it. Before setting out for a dacoity, the men engaged would assemble at the hut of Mīthu Bhūkia, and, burning a lamp before him, ask for an omen; if the wick of the lamp drooped the omen was propitious, and the men present then set out at once on the raid without returning home. They might not speak to each other nor answer if challenged; for if any one spoke the charm would be broken and the protection of Mīthu Bhūkia removed; and they should either return to take the omens again or give up that particular dacoity altogether.203 It has been recorded as a characteristic trait of Banjāras that they will, as a rule, not answer if spoken to when engaged on a robbery, and the custom probably arises from this observance; but the worship of Mīthu Bhūkia is now frequently neglected. After a successful dacoity a portion of the spoil would be set apart for Mīthu Bhūkia, and of the balance the Nāik or headman of the village received two shares if he participated in the crime; the man who struck the first blow or did most towards the common object also received two shares, and all the rest one share. With Mīthu Bhūkia’s share a feast was given at which thanks were returned to him for the success of the enterprise, a burnt offering of incense being made in his tent and a libation of liquor poured over the flagstaff. A portion of the food was sent to the women and children, and the men sat down to the feast. Women were not allowed to share in the worship of Mīthu Bhūkia nor to enter his hut.

12. Siva Bhāia.

Another favourite deity is Siva Bhāia, whose story is given by Colonel Mackenzie204 as follows: “The love borne by Māri Māta, the goddess of cholera, for the handsome Siva Rāthor, is an event of our own times (1874); she proposed to him, but his heart being pre-engaged he rejected her; and in consequence his earthly bride was smitten sick and died, and the hand of the goddess fell heavily on Siva himself, thwarting all his schemes and blighting his fortunes and possessions, until at last he gave himself up to her. She then possessed him and caused him to prosper exceedingly, gifting him with supernatural power until his fame was noised abroad, and he was venerated as the saintly Siva Bhāia or great brother to all women, being himself unable to marry. But in his old age the goddess capriciously wished him to marry and have issue, but he refused and was slain and buried at Pohur in Berār. A temple was erected over him and his kinsmen became priests of it, and hither large numbers are attracted by the supposed efficacy of vows made to Siva, the most sacred of all oaths being that taken in his name.” If a Banjāra swears by Siva Bhāia, placing his right hand on the bare head of his son and heir, and grasping a cow’s tail in his left, he will fear to perjure himself, lest by doing so he should bring injury on his son and a murrain on his cattle.205

13. Worship of cattle.

Naturally also the Banjāras worshipped their pack-cattle.206 “When sickness occurs they lead the sick man to the feet of the bullock called Hātadiya.207 On this animal no burden is ever laid, but he is decorated with streamers of red-dyed silk, and tinkling bells with many brass chains and rings on neck and feet, and silken tassels hanging in all directions; he moves steadily at the head of the convoy, and at the place where he lies down when he is tired they pitch their camp for the day; at his feet they make their vows when difficulties overtake them, and in illness, whether of themselves or their cattle, they trust to his worship for a cure.”

14. Connection with the Sikhs.

Mr. Balfour also mentions in his paper that the Banjāras call themselves Sikhs, and it is noticeable that the Chāran subcaste say that their ancestors were three Rājpūt boys who followed Guru Nānak, the prophet of the Sikhs. The influence of Nānak appears to have been widely extended over northern India, and to have been felt by large bodies of the people other than those who actually embraced the Sikh religion. Cumberlege states208 that before starting to his marriage the bridegroom ties a rupee in his turban in honour of Guru Nānak, which is afterwards expended in sweetmeats. But otherwise the modern Banjāras do not appear to retain any Sikh observances.

15. Witchcraft.

“The Banjāras,” Sir A. Lyall writes,209 “are terribly vexed by witchcraft, to which their wandering and precarious existence especially exposes them in the shape of fever, rheumatism and dysentery. Solemn inquiries are still held in the wild jungles where these people camp out like gipsies, and many an unlucky hag has been strangled by sentence of their secret tribunals.” The business of magic and witchcraft was in the hands of two classes of Bhagats or magicians, one good and the other bad,210 who may correspond to the European practitioners of black and white magic. The good Bhagat is called Nimbu-kātna or lemon-cutter, a lemon speared on a knife being a powerful averter of evil spirits. He is a total abstainer from meat and liquor, and fasts once a week on the day sacred to the deity whom he venerates, usually Mahādeo; he is highly respected and never panders to vice. But the Jānta, the ‘Wise or Cunning Man,’ is of a different type, and the following is an account of the devilry often enacted when a deputation visited him to inquire into the cause of a prolonged illness, a cattle murrain, a sudden death or other misfortune. A woman might often be called a Dākun or witch in spite, and when once this word had been used, the husband or nearest male relative would be regularly bullied into consulting the Jānta. Or if some woman had been ill for a week, an avaricious211 husband or brother would begin to whisper foul play. Witchcraft would be mentioned, and the wise man called in. He would give the sufferer a quid of betel, muttering an incantation, but this rarely effected a cure, as it was against the interest of all parties that it should do so. The sufferer’s relatives would then go to their Nāik, tell him that the sick person was bewitched, and ask him to send a deputation to the Jānta or witch-doctor. This would be at once despatched, consisting of one male adult from each house in the hamlet, with one of the sufferer’s relatives. On the road the party would bury a bone or other article to test the wisdom of the witch-doctor. But he was not to be caught out, and on their arrival he would bid the deputation rest, and come to him for consultation on the following day. Meanwhile during the night the Jānta would be thoroughly coached by some accomplice in the party. Next morning, meeting the deputation, he would tell every man all particulars of his name and family; name the invalid, and tell the party to bring materials for consulting the spirits, such as oil, vermilion, sugar, dates, cocoanut, chironji,212 and sesamum. In the evening, holding a lamp, the Jānta would be possessed by Māriai, the goddess of cholera; he would mention all particulars of the sick man’s illness, and indignantly inquire why they had buried the bone on the road, naming it and describing the place. If this did not satisfy the deputation, a goat would be brought, and he would name its sex with any distinguishing marks on the body. The sick person’s representative would then produce his nazar or fee, formerly Rs. 25, but lately the double of this or more. The Jānta would now begin a sort of chant, introducing the names of the families of the kuri other than that containing her who was to be proclaimed a witch, and heap on them all kinds of abuse. Finally, he would assume an ironic tone, extol the virtues of a certain family, become facetious, and praise its representative then present. This man would then question the Jānta on all points regarding his own family, his connections, worldly goods, and what gods he worshipped, ask who was the witch, who taught her sorcery, and how and why she practised it in this particular instance. But the witch-doctor, having taken care to be well coached, would answer everything correctly and fix the guilt on to the witch. A goat would be sacrificed and eaten with liquor, and the deputation would return. The punishment for being proclaimed a Dākun or witch was formerly death to the woman and a fine to be paid by her relatives to the bewitched person’s family. The woman’s husband or her sons would be directed to kill her, and if they refused, other men were deputed to murder her, and bury the body at once with all the clothing and ornaments then on her person, while a further fine would be exacted from the family for not doing away with her themselves. But murder for witchcraft has been almost entirely stopped, and nowadays the husband, after being fined a few head of cattle, which are given to the sick man, is turned out of the village with his wife. It is quite possible, however, that an obnoxious old hag would even now not escape death, especially if the money fine were not forthcoming, and an instance is known in recent times of a mother being murdered by her three sons. The whole village combined to screen these amiable young men, and eventually they made the Jānta the scapegoat, and he got seven years, while the murderers could not be touched. Colonel Mackenzie writes that, “Curious to relate, the Jāntas, known locally as Bhagats, in order to become possessed of their alleged powers of divination and prophecy, require to travel to Kazhe, beyond Surat, there to learn and be instructed by low-caste Koli impostors.” This is interesting as an instance of the powers of witchcraft being attributed by the Hindus or higher race to the indigenous primitive tribes, a rule which Dr. Tylor and Dr. Jevons consider to hold good generally in the history of magic.

16. Human sacrifice.

Several instances are known also of the Banjāras having practised human sacrifice. Mr. Thurston states:213 “In former times the Lambādis, before setting out on a journey, used to procure a little child and bury it in the ground up to the shoulders, and then drive their loaded bullocks over the unfortunate victim. In proportion to the bullocks thoroughly trampling the child to death, so their belief in a successful journey increased.” The Abbé Dubois describes another form of sacrifice:214

“The Lambādis are accused of the still more atrocious crime of offering up human sacrifices. When they wish to perform this horrible act, it is said, they secretly carry off the first person they meet. Having conducted the victim to some lonely spot, they dig a hole in which they bury him up to the neck. While he is still alive they make a sort of lamp of dough made of flour, which they place on his head; this they fill with oil, and light four wicks in it. Having done this, the men and women join hands and, forming a circle, dance round their victim, singing and making a great noise until he expires.” Mr. Cumberlege records215 the following statement of a child kidnapped by a Banjāra caravan in 1871. After explaining how he was kidnapped and the tip of his tongue cut off to give him a defect in speech, the Kunbi lad, taken from Sāhungarhi, in the Bhandāra District, went on to say that, “The tānda (caravan) encamped for the night in the jungle. In the morning a woman named Gangi said that the devil was in her and that a sacrifice must be made. On this four men and three women took a boy to a place they had made for pūja (worship). They fed him with milk, rice and sugar, and then made him stand up, when Gangi drew a sword and approached the child, who tried to run away; caught and brought back to this place, Gangi, holding the sword with both hands and standing on the child’s right side, cut off his head with one blow. Gangi collected the blood and sprinkled it on the idol; this idol is made of stone, is about 9 inches high, and has something sparkling in its forehead. The camp marched that day, and for four or five days consecutively, without another sacrifice; but on the fifth day a young woman came to the camp to sell curds, and having bought some, the Banjāras asked her to come in in the evening and eat with them. She did come, and after eating with the women slept in the camp. Early next morning she was sacrificed in the same way as the boy had been, but it took three blows to cut off her head; it was done by Gangi, and the blood was sprinkled on the stone idol. About a month ago Sitārām, a Gond lad, who had also been kidnapped and was in the camp, told me to run away as it had been decided to offer me up in sacrifice at the next Jiuti festival, so I ran away.” The child having been brought to the police, a searching and protracted inquiry was held, which, however, determined nothing, though it did not disprove his story.

17. Admission of outsiders: kidnapped children and slaves.

The Banjāra caste is not closed to outsiders, but the general rule is to admit only women who have been married to Banjāra men. Women of the lowest and impure castes are excluded, and for some unknown reason the Patwas216 and Nunias are bracketed with these. In Nimār it is stated that formerly Gonds, Korkus and even Balāhis217 might become Banjāras, but this does not happen now, because the caste has lost its occupation of carrying goods, and there is therefore no inducement to enter it. In former times they were much addicted to kidnapping children—these were whipped up or enticed away whenever an opportunity presented itself during their expeditions. The children were first put into the gonis or grain bags of the bullocks and so carried for a few days, being made over at each halt to the care of a woman, who would pop the child back into its bag if any stranger passed by the encampment. The tongues of boys were sometimes slit or branded with hot gold, this last being the ceremony of initiation into the caste still used in Nimār. Girls, if they were as old as seven, were sometimes disfigured for fear of recognition, and for this purpose the juice of the marking-nut218 tree would be smeared on one side of the face, which burned into the skin and entirely altered the appearance. Such children were known as Jāngar. Girls would be used as concubines and servants of the married wife, and boys would also be employed as servants. Jāngar boys would be married to Jāngar girls, both remaining in their condition of servitude. But sometimes the more enterprising of them would abscond and settle down in a village. The rule was that for seven generations the children of Jāngars or slaves continued in that condition, after which they were recognised as proper Banjāras. The Jāngar could not draw in smoke through the stem of the huqqa when it was passed round in the assembly, but must take off the stem and inhale from the bowl. The Jāngar also could not eat off the bell-metal plates of his master, because these were liable to pollution, but must use brass plates. At one time the Banjāras conducted a regular traffic in female slaves between Gujarāt and Central India, selling in each country the girls whom they had kidnapped in the other.219

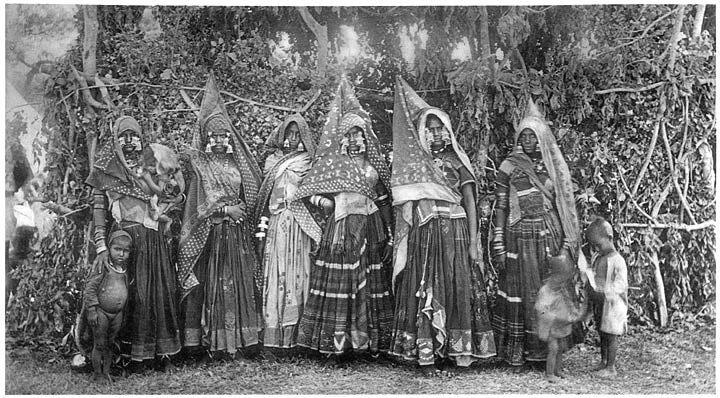

Banjāra women with the singh or horn.

18. Dress.

Up to twelve years of age a Chāran girl only wears a skirt with a shoulder-cloth tucked into the waist and carried over the left arm and the head. After this she may have anklets and bangles on the forearm and a breast-cloth. But until she is married she may not have the wānkri or curved anklet, which marks that estate, nor wear bone or ivory bangles on the upper arm.220 When she is ten years old a Labhāna girl is given two small bundles containing a nut, some cowries and rice, which are knotted to two corners of the dupatta or shoulder-cloth and hung over the shoulder, one in front and one behind. This denotes maidenhood. The bundles are considered sacred, are always knotted to the shoulder-cloth in wear, and are only removed to be tucked into the waist at the girl’s marriage, where they are worn till death. These bundles alone distinguish the Labhāna from the Mathuria woman. Women often have their hair hanging down beside the face in front and woven behind with silver thread into a plait down the back. This is known as Anthi, and has a number of cowries at the end. They have large bell-shaped ornaments of silver tied over the head and hanging down behind the ears, the hollow part of the ornament being stuffed with sheep’s wool dyed red; and to these are attached little bells, while the anklets on the feet are also hollow and contain little stones or balls, which tinkle as they move. They have skirts, and separate short cloths drawn across the shoulders according to the northern fashion, usually red or green in colour, and along the skirt-borders double lines of cowries are sewn. Their breast-cloths are profusely ornamented with needle-work embroidery and small pieces of glass sewn into them, and are tied behind with cords of many colours whose ends are decorated with cowries and beads. Strings of beads, ten to twenty thick, threaded on horse-hair, are worn round the neck. Their favourite ornaments are cowries,221 and they have these on their dress, in their houses and on the trappings of their bullocks. On the arms they have ten or twelve bangles of ivory, or in default of this lac, horn or cocoanut-shell. Mr. Ball states that he was “at once struck by the peculiar costumes and brilliant clothing of these Indian gipsies. They recalled to my mind the appearance of the gipsies of the Lower Danube and Wallachia.”222 The most distinctive ornament of a Banjāra married woman is, however, a small stick about 6 inches long made of the wood of the khair or catechu. In Nimār this is given to a woman by her husband at marriage, and she wears it afterwards placed upright on the top of the head, the hair being wound round it and the head-cloth draped over it in a graceful fashion. Widows leave it off, but on remarriage adopt it again. The stick is known as chunda by the Banjāras, but outsiders call it singh or horn. In Yeotmāl, instead of one, the women have two little sticks fixed upright in the hair. The rank of the woman is said to be shown by the angle at which she wears this horn.223 The dress of the men presents no features of special interest. In Nimār they usually have a necklace of coral beads, and some of them carry, slung on a thread round the neck, a tin tooth-pick and ear-scraper, while a small mirror and comb are kept in the head-cloth so that their toilet can be performed anywhere.