Полная версия

India

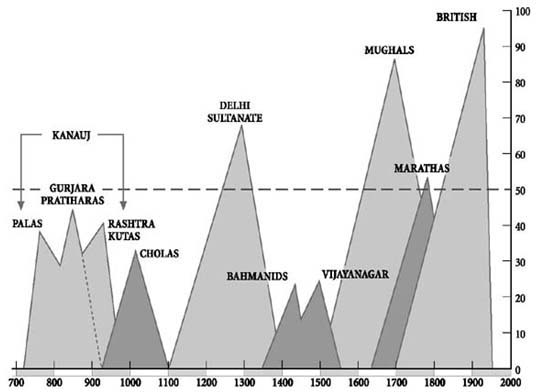

THE PEAKS AND TROUGHS OF DOMINION

There are, of course, exceptions; in India there are always exceptions, mostly big ones. The Himalayas, the most prominent feature on the face of the earth, grandly shield the subcontinent from the rest of Asia; likewise the Western Ghats form a long and craggy rampart against the Arabian Sea. Both are very much part of India, the Himalayas as the abode of its gods, the Ghats as the homeland of the martial Marathas, and both as the source of most of India’s rivers. But it is as if these ranges have been pushed to the side, marginalised and then regimented like the plunging V of the south Asian coastline, so as to clear, define and contain the vast internal arena on which Indian history has been staged.

An instructive comparison might be with one of Eurasia’s other subcontinents – like Europe. Europe minus the erstwhile Soviet Union comprises about the same area as the Indian subcontinent (over four million square kilometres). But uniform and homogeneous it is not. Mountain chains like the Alps and the Pyrenees, plus a heavily indented coastline and a half-submerged continental shelf, partition the landmass into a tangle of semi-detached peninsulas (Iberia, Scandinavia), offshore islands (Britain, Ireland) and mountain enclaves (Switzerland, Scotland). The geographical configuration favours separation, isolation and regional identity. Corralled into such natural compartments, tribes could become nations and nations become states, confident of their territorial distinction.

A diagrammatic chronology for the major dynasties giving approximate indication of their territorial reach

But if for Europe geography decreed fragmentation, for India it intended integrity. Here were no readily defensible peninsulas, no snowy barriers to internal communication and few waterways which were not readily crossable for much of the year. The forests, once much more widespread than today, were mostly of dry woodland which afforded, besides shelter and sanctuary to reclusive tribes and assorted renunciates, a larder of exotic products (game, honey, timbers, resins) for the plains dwellers. Only in some peripheral regions like Kerala and Assam did this sylvan canopy become compacted into impenetrable rainforest. Wetlands also were once much more extensive. In what are now Bangladesh and Indian West Bengal, the Ganga (Ganges) and the Brahmaputra rivers enmesh to filter seawards in a maze of channels which forms the world’s most extensive delta. Semi-submerged as well as densely wooded, most of Bengal made a late entry onto the stage of history. But wetlands, too, supplied a variety of desirable products, and during the dry summer months they contracted dramatically. Different ecological zones complemented one another, encouraging symbiosis and exchange. Nomads and graziers, seers and pilgrims, traders and troops might pass freely across the face of such a congenial land. It seemed ready-made for integration and empire.

Climate decided otherwise. ‘India is an amalgam of areas, and also of disparate experiences, which never quite succeeded in forming a single whole;’4 only the British, according to Fernand Braudel, ever ruled the entire subcontinent; integration proved elusive because the landmass was too large and the population too numerous and diverse. But surprisingly, considering Braudel’s emphasis on environments, he ignores a more obvious explanation. Settlement was not uniform and integration not easily achieved because what geography had so obligingly joined together, hydrography put asunder.

India enjoys tropical temperatures, yet during most of the year over most of the country there is no rain. Growth therefore depends on short seasonal precipitations, as epitomised by the south-west monsoon which sweeps unevenly across nearly the whole country between June and September. The pattern of rainfall, and the extent to which particular landscapes can benefit from it by slowing and conserving its run-off, were the decisive factors in determining patterns of settlement. Where water was readily available for longest, there agriculture could prosper, populations grow, and societies develop. Where not, stubby fingers of scrub, broad belts of desert and bulging plateaux of rock obtruded, cutting off the favoured areas of settlement one from the other.

Like lakes, long rivers with little fall, especially if their flood is prolonged by snow-melt as with the Ganga and the Indus, serve the purpose of conserving water well. Much of northern India relies on its rivers, although the lands they best serve, as also their braided courses and even their number, have changed over the centuries. Depending on one’s chosen date, Indian history begins somewhere on the banks of north India’s litany of great rivers – either along the lower Indus or amongst the ‘five rivers’ (panj-ab, hence Panjab, or Punjab) which are its tributaries, or in the ‘two rivers’ (do-ab, hence Doab) region between the Jamuna (Jumna) and the Ganga, or along the middle Ganga in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

North India’s mighty river systems ordained much the most extensive of these well-watered zones of agricultural settlement; and though these zones were several, in the course of the first millennium BC they tended to become contiguous, thus creating a corridor of patchy cultivation and settlement from the north-west in what is now Pakistan to Bihar in the east. Here commercial exchange, cultural uniformity and political rivalry got off to an early start. The corridor became a broad swathe of competing states, cherishing similar ideals, revering common traditions and inviting claims of paramountcy. For empire-builders like the Mauryas, Guptas and Vardhanas, this was where the idea of Indian dominion began.

Elsewhere surface reservoirs supplemented rivers as a useful means of water conservation if the terrain permitted. In the deep south, weeks after Tamil Nadu’s November rains have ceased, what looks from the air like chronic flooding proves to be a cunningly designed patchwork of fields with their sides so embanked as to form reservoirs, or ‘tanks’. When, after carefully managed use and the inevitable evaporation, the water is nearly exhausted, the tank can itself be planted with a late rice crop. Since the peninsula lacks the vast alluvial plains of the north and has to accommodate hills like the Western Ghats, zones favourable to agricultural settlement were here smaller although numerous and, in cases like the Kerala coast, exceptionally well watered.

In other regions geology did its best for moisture conservation by trapping water underground. From wells it could then be laboriously hauled to the surface for limited irrigation. For the intervening zones of greatest aridity, this sub-surface water was the only source available during most of the year. And since about half the subcontinent receives less than eighty centimetres of rain per year, these arid zones were large. By supposing a continuity between the western deserts of Sind/Rajasthan and the drier parts of central India plus the great Deccan plateau of the peninsula, a broad north – south divide has sometimes been inferred. In fact the terminology here is too vague (even the Deccan is more a designation of convenience than a natural feature). Moreover, considerable rivers traverse this divide: the Chambal and Betwa, tributaries of the Jamuna, afford north – south corridors between the Gangetic plain and the peninsula. And slicing across the waist of India, the west-flowing Narmada forms a much more obvious north – south divide; indeed it figures historically as something of an Indian Rubicon between the north and the peninsula. Micro-zones with excellent water conservation also dot both Rajasthan and the Deccan; in historical times they would sustain a succession of the most formidable dynasties.

As with the forests and wetlands, the dry-lands were not without their own sparser populations, typically herdsmen and warriors. As barriers, dry regions are hardly as formidable as the seas and mountains of Europe. But as boundaries and frontier zones they did have something of the same effect, encouraging separation, fostering distinction and, in time, confronting ambitious rulers with the great Indian paradox of a land that invited dominion full of lesser rulers who felt bound to resist it.

The socio-cultural dimension to this climate-induced paradox would be even more enduring. Indeed it largely accounts for the strength of ‘regional’ sentiment in the subcontinent today. In those favoured, because well-watered, zones where settlement became concentrated, surplus agricultural production encouraged the development of non-agricultural activities. Archaeologists are alerted to this process by the distribution of more standardised implements, weapons and styles of pottery. These things also help in the identification of the favoured areas – most notably, and at different times, that great trail across the north from the Indus to the Gangetic basin, plus Gujarat, Malwa and the Orissan littoral in mid-India. In the south a similar diversification is inferred, although here the archaeological display-case remains somewhat empty. Save for a few Stone Age productions, south India’s history has to wait until jump-started by a remarkable literary outpouring at the very end of the first millennium BC.

As crafts and trades prospered, specialisation encouraged congregation, and congregation urbanisation. Within the same favoured enclaves, ideological conformity, social stratification and political formation followed. The models for each – for an effective religion, a harmonious society and a legitimate state – married local elements and imperatives with a set of norms derived from the propagandised traditions of an Indo-Aryan people who had emerged in north India by 1000 BC. These Indo-Aryans were probably outsiders and, as well as a strong sense of community centred on elaborate rites of sacrifice, they possessed in the Sanskrit language an exceptionally versatile and persuasive medium of communication. Had India been as open and uniform a land as geography suggests, no doubt Sanskrit and its speakers would speedily have prevailed. They did do so over much of north India, but not speedily and not without compromise. Further afield, in west, east and central India and the Deccan, the process somewhat misleadingly known as ‘Aryanisation’ took even longer and involved so much compromise with local elements that hybridisation seems a fairer description. From it emerged most of the different languages and different social conformations which, heightened by different historical experiences, have given India its regional diversity, and which still distinguish the Bengali from the Gujarati or the Panjabi from the Maratha.

The pantheon of spirits and deities worshipped in each zone, or region, typified this process of hybridisation, with Indo-Aryan gods forsaking their original personae to accommodate a host of local cults. Thus did Lord Vishnu acquire his long list of avatars or ‘incarnations’. In parts of India this process of divine hybridisation is still continuing. Every year each village in the vicinity of Pudukottai in Tamil Nadu commissions from the local potter a large terracotta horse for the use of Lord Ayanar. Astride his splendid new mount, Ayanar will ride the village bounds at night, protecting the crops and warding off smallpox. But who is this Ayanar? None other than Lord Shiva, they tell you. The pan-Indian Shiva, himself an amalgam of various cults, looks to be only now in the process of usurping the Tamil Lord Ayanar. But it could be the other way round. To the people of Pudukottai it is Ayanar who is assuming the attributes of Shiva.

As with gods, so with the different languages spoken in India’s zonal regions. In its earliest form Marathi, the language now mainly spoken in Maharashtra, betrayed Dravidian as well as Sanskrit features. At some point a local form of early Dravidian, a language family now represented only in the south, is thought to have been overlain by the more prestigious and universal Sanskrit. But the precedence as between local indigenous elements and Sanskritic or Aryan influences is not clear. Did Sanskrit speakers domiciled in Maharashtra slowly absorb proto-Dravidian inflexions? Or was that too the other way round?

A more clear-cut example of Aryanisation/Sanskritisation is provided by the many attempts to replicate the topography featured in the Sanskrit epics. By word of mouth core elements of the Mahabharata and Ramayana had early penetrated to most of India. By the late centuries of the first millennium BC, even deep in the Tamil south they knew of the Pandava heroes who had fought the great Bharata war for hegemony in the Ganga-Jamuna Doab and of Rama and Lakshmana’s expedition from Ayodhya to rescue the Lady Sita. Clearly these stories had a universal appeal, and in a trail of still recognisable place-names their hallowed topography was faithfully adopted by far-flung rulers anxious to garner prestige. The trail of ‘Ayodhyas’, ‘Mathuras’, ‘Kosalas’, ‘Kambojas’ and so on would stretch way beyond India itself, most notably into areas of Indian influence in south-east Asia. And like that hybridisation of deities, it continues. In Karnataka a Kannada writer complained to me that, despite the best efforts of the state government in Bangalore to promote the Kannada language, villagers still persisted in Sanskritising the names of their villages in a bid for greater respectability, then lobbying the Post Office to recognise the change.

As well as renaming local sites and features, some kings actually tried to refashion them in accordance with the idealised models and layouts of Sanskrit literary tradition. The Rashtrakuta rulers of eighth- to tenth-century Maharashtra evidently conceived their sculpted temple-colossus at Ellora as a replica of the Himalayas. It was named for Shiva as Lord of Mount Kailas (a peak now in Tibet) and was provided with a complement of Himalayan rivers in the form of voluptuous river deities like the Ladies Ganga and Jamuna. In a bid to appropriate the same sacred geography the great Cholas went one better, and actually hauled quantities of water all the way from the Ganga, a good two thousand kilometres distant, to fill their temple tanks and waterways around Tanjore. Thus was authenticated their claim to have recreated the north Indian ‘holy land’ in the heart of Tamil Nadu.

Geography, like history, was seen as something which might be made to repeat itself. In tableaux like that of the Taj Mahal the Mughal emperors strove to realise the Islamic ideal of a paradise composed of scented verdure, running water and white marble. Later, in leafy hill-stations, the British aimed at recreating their own idealised environment of green gables and lych-gated churchyards connected by perilous pathways and fuchsia hedges; new names like ‘Annandale’ and ‘Wellington’ were added to the map; existing nomenclatures were bowdlerised and anglicised.

Now they are being vernacularised. This is a confusing time for both visitors to India and those who write about it. With the process of revision far from complete, the chances of finding spellings and appellations which are recognisable and acceptable to all are slim. At the risk of offending some, I have continued to call Mumbai ‘Bombay’, Kolkota ‘Calcutta’ and Chennai ‘Madras’; to non-Indians these names are still the more familiar. On the other hand I have adopted several spellings – for instance ‘Pune’ for Poona, ‘Awadh’ for Oudh, ‘Ganga’ for Ganges, ‘Panjab’ for Punjab – which may not be familiar to non-Indians; they are, however, in general use in India and have become standard in South Asian studies.

For anyone ignorant of both Sanskrit and Persian, transliteration poses another major problem. Again, I lay no claim to consistency. For the most part I have kept the terminal ‘a’ of many Sanskrit words (Rama for Ram, Ramayana for Ramayan, etc.) and used ‘ch’ for ‘c’ (as in Chola) and ‘sh’ for most of the many Sanskrit ‘s’s (Vishnu for Visnu, Shiva for Siva, Shatavahana and Shaka for Satavahana and Saka). The knowledgeable reader will doubtless find many lapses for which the author, not the typesetter, is almost certainly responsible – as indeed he is for all the errors and omissions, the generalisations and over-simplifications, to which five thousand years of tumultuous history is liable.

1 The Harappan World C3000–1700 BC

THE BREAKING OF THE WATERS

IN HINDU TRADITION, as in Jewish and Christian tradition, history of a manageable antiquity is sometimes said to start with the Flood. Flushing away the obscurities of an old order, the Flood serves a universal purpose in that it establishes its sole survivor as the founder of a new and homogeneous society in which all share descent from a common ancestor. A new beginning is signalled; a lot of begetting follows.

In the Bible the Flood is the result of divine displeasure. Enraged by man’s disobedience and wickedness, God decides to cancel his noblest creation; only the righteous Noah and his dependants are deemed worthy of survival and so of giving mankind a second chance. Very different, on the face of it, is the Indian deluge. According to the earliest of several accounts, the Flood which afflicted India’s people was a natural occurrence. Manu, Noah’s equivalent, survived it thanks to a simple act of kindness. And, amazingly for a society that worshipped gods of wind and storm, no deity receives a mention.

When Manu was washing his hands one morning, a small fish came into his hands along with the water. The fish begged protection from Manu saying ‘Rear me. I will save thee.’ The reason stated was that the small fish was liable to be devoured by the larger ones, and it required protection till it grew up. It asked to be kept in a jar, and later on, when it outgrew that, in a pond, and finally in the sea. Manu acted accordingly.

[One day] the fish forewarned Manu of a forthcoming flood, and advised him to prepare a ship and enter into it when the flood came. The flood began to rise at the appointed hour, and Manu entered the ship. The fish then swam up to him, and he tied the rope of the ship to its horn [perhaps it was a swordfish], and thus passed swiftly to the yonder northern mountain. There Manu was directed to ascend the mountain after fastening the ship to a tree, and to disembark only after the water had subsided.

Accordingly he gradually descended, and hence the slope of the northern mountain is called Manoravataranam, or Manu’s descent. The waters swept away all the three heavens, and Manu alone was saved.1

Such is the earliest version of the Flood as recorded in the Satapatha Brahmana, one of several wordy appendices to the sacred hymns known as the Vedas which are themselves amongst the oldest religious compositions in the world. Couched in the classical language of Sanskrit, some of the Vedas date from before the first millennium BC. Together with later works like the Brahmanas, plus the two great Sanskrit epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, they comprise a glorious literary heritage whence all knowledge of India’s history prior to C500 BC has traditionally been derived.

Brief and to the point, the story of Manu and the Flood served its purpose of introducing a new progenitor of the human race and, incidentally, explaining the name of a mountain. Such, however, was too modest an interpretation for later generations. Myth, the smoke of history, is seen to signal new and more relevant meanings when espied from the distance of later millennia. In time the predicament of the small fish liable to be devoured by larger fish became a Sanskrit metaphor for an anarchic state of affairs (matsya-nyaya) equivalent to ‘the law of the jungle’ in English. Manu’s flood, like Noah’s, came to be seen as the means of putting a stop to this chaos. And who better to orchestrate matters and so save mankind than Lord Vishnu? A minor deity when the Vedas were composed, Vishnu had since soared to prominence as the great preserver of the world in the Hindu pantheon and the second member of its trinity. Thus, in due course, the Flood became a symbol of order-out-of-chaos through divine intervention, and the fish (matsya) came to be recognised as the first of the nine incarnations (avatara) of Lord Vishnu. Myth, howsoever remote, serves the needs of the moment. So does history, in India as elsewhere.

Some historians have dated the Flood very precisely to 3102 BC, this being the year when, by elaborate computation, they conclude that our current era, the Kali Yug in Indian cosmology, began and when Manu became the progenitor of a new people as well as their first great king and law-giver. It is also the first credible date in India’s history and, being one of such improbable exactitude, it deserves respect.

Other historians, while conceding the importance of 3102 BC, have declared it to be not the date of the Flood but of the great Bharata war. A Trojan-style conflict fought in the vicinity of Delhi, the war involved both gods and men and was immortalised in the Sanskrit verse epic known as the Mahabharata, the composition of whose roughly 100,000 stanzas constituted something of an epic in itself. This war, not the flood, was the event that marked the beginning of our present era and must, it is argued, therefore belong to the year 3102 BC. Complex astronomical calculations are deployed in support of this dating, and an inscription carved on a stone temple at Aihole in the south Indian state of Karnataka is said to confirm it.

But the Aihole memorialist, endowing his temple 1600 kilometres from Delhi and nearly four thousand years later, may have got it wrong. According to the genealogical listings in the Puranas, a later collection of ‘ancient legends’, ninety-five generations passed away between the Flood and the war; other evidence based on sterner, more recent, scholarship agrees that the war was much later than the fourth millennium BC. This greatest single event in India’s ancient history, and the inspiration for the world’s longest poem, did not occur until ‘C1400 BC’ according to the History and Culture of the Indian People, a standard work of many volumes commissioned in the 1950s to celebrate India’s liberation from foreign rule and foreign scholarship.

Nevertheless, 3102 BC sticks in the historical gullet. Such are the dismal uncertainties of early Indian chronology that no slip of the chisel is going to deny the historian the luxury of a real date. Corroboration of the idea that it may, after all, apply to a Flood has since come from the excavations in distant Iraq of one of Mesopotamia’s ancient civilisations. There too archaeologists have found evidence of an appalling inundation. It submerged the Sumerian city of Shuruppak, and has been dated with some confidence to the late fourth millennium BC. In fact, 3102 BC would suit it very well.

This Sumerian inundation, and the local Genesis story in the Epic of Gilgamesh which probably derived from it, is taken to be the origin of the legend of the Flood which eventually found its way into Jewish and Christian tradition. Yet in many respects the Sumerian account is more closely echoed in the Indian version than in the Semitic. For instance, just as in later Hindu tradition Manu’s fish becomes an incarnation of the great god Vishnu, so the Sumerian deity responsible for saving mankind is often represented in the form of a fish. ‘It is the agreement in details which is so striking,’ according to Romila Thapar.2 The details argue strongly for some common source for this most popular of Genesis myths, and scholars like Thapar, ever ready to expose cultural plagiarism, see both Manu and Noah as relocated manifestations of a Sumerian prototype.

The tendency to synchronise and subordinate things Indian to parallel events and achievements in the history of countries to the west of India is a recurrent theme in Indian historiography and has rightly incurred the wrath of some Indian historians. So much so that they sometimes go to the other extreme of denying that any creative impetus, any technological invention, even any stylistic convention, ever reached India from the west – or, indeed, the West. And in the case of the Flood they may have a point. Subject to the annual deluge of the monsoon and living for the most part on the flat alluvial plains created by notoriously errant river systems, the people of north India have always had far more experience of floods, and far more reason to fear them, than their neighbours in the typically more arid lands of western Asia.