Полная версия

India

The coins and inscriptions of the first few centuries BC/AD certainly testify to alien rulers, but of battles we know nothing, let alone who won them. Marital alliances, economic crises, coups and assassinations have probably triggered more dynastic changes than have successful invasions. Given the crisis of political legitimacy, given too the obscure origins of most indigenous dynasties of the period, plus the absence of anything like a national consciousness, there may have been no fundamental objection to accepting as kings men with strange names, remote origins and unusual headgear.

The Pahlavans/Parthians quickly disappeared from the Indian scene. They would be resurrected only once, and much later, as the doubtful antecedents of the Pallavas of Kanchipuram, a distinguished dynasty but one separated from the Parthians by three centuries and the breadth of the entire subcontinent. The Shakas/Scythians, segmenting into a variety of junior kingdoms, or satrapies, and readily assimilating to Indian society, made a more lasting impression. At one time they penetrated to Mathura and Ujjain but would latterly be penned into Saurashtra (in Gujarat); thence, as the ‘Western Satraps’, they would resurface briefly in the first and second centuries AD. Only the Yueh-chi or Kushanas, and in particular their great king Kanishka, would establish anything like an Indian empire.

Coins, plus an inscription found at Taxila, bear early testimony to the pretensions of the Kushana. ‘Maharajah’, ‘King of Kings’, ‘Son of God’, ‘Saviour’, ‘Great One’, ‘Lord of all Lands’, ‘Caesar’ and other such titles are reeled off as if the incumbent wished to lay claim to every source of sovereignty going. ‘Son of God’ is thought to be a legacy of the Yueh-chi’s familiarity with China and its celestial rulers; ‘King of Kings’ was borrowed from the Shakas, who had imitated the Achaemenids of Iran; ‘Saviour’ came from the Greeks; ‘Caesar’ from the Romans. The coins are of the highest quality and show a switch to Roman weight standards; possibly they were actually recast Roman aurei. But to accommodate such fanfares of majesty in the limited space available, the name of the king in question was often left out. The succession of the Kushana kings is therefore far from certain. It is thought that there was a Kujula Kadphises and then a Wima Kadphises, evidently another devotee of Lord Shiva, who between them added to their Afghan territories those of Gandhara, the Panjab, and the Ganga-Jamuna Doab at least as far south as Mathura.

After these Kadphiseses came, probably, Kanishka. Inscriptions referring to him (or to the era which supposedly began with his accession) are found over a vast area extending from the Oxus frontier of Afghanistan to Varanasi and Sanchi. Tradition further testifies to his conquest of Magadha and to vast responsibilities in and beyond the western Himalayas, including Kashmir and Khotan in Sinkiang. Buddhist sources, to which we are indebted for much of this information, hail him as another Menander or Ashoka; he showered the sangha (the monastic community) with patronage, presided over the fourth Buddhist council and encouraged a new wave of missionary activity. At Purushpura, or Peshawar, his capital still boasts the foundations of a truly colossal stupa. Nearly a hundred metres in diameter and reliably reported to have been two hundred metres high, it must have ranked as one of the then wonders of the world.

Mathura on the Jamuna seems to have served as a subsidiary capital, and nearby have been found suitably massive statues of Wima Kadphises and of Kanishka himself. Unfortunately both have been decapitated. While for the Greeks, thanks to their coins, we have notable heads but few torsos, for the Kushanas we have notable torsos but few heads. Kanishka stands in challenging pose, his outsize feet encased in quilted felt boots and splayed outwards. The full-frontal presentation reveals a belted tunic beneath a stiff ankle-length coat that looks as if it could have been of leather. One hand rests on a grounded sword of skull-splitting potential, the other clutches an elaborate contraption sometimes described as a mace but which could equally be some kind of crossbow. Hopelessly overdressed for the Indian plains and most un-Indian in its angular and uncompromising posture, this statue evokes the harsh landscapes whence the Kushana came and where, while campaigning in Sinkiang, Kanishka is said to have died. Although surely not ‘one of the finest works of art produced on Indian soil’, his statue is indeed ‘unique as the only Indian work of art to show a foreign stylistic influence that has not come from Iran or the Hellenistic or Roman world’.6

Kanishka’s successors, many with names also ending in ‘-ishka’, continued Kushana rule for another century or more. As with other august dynasties, their territories are assumed to have shrunk as their memorials became fewer and nearer between; in the course of time the Kushanas dwindled to being just one of many petty kingdoms in the north-west. Unfortunately it is impossible to be precise about their chronology since all inscriptions are dated from the accession of Kanishka, itself a subject of yawning complexity which numerous international gatherings on several continents have failed to resolve. Today’s Republic of India, as well as having two names for the country (India and Bharat), has two systems of dating, one the familiar Gregorian calendar of BC/AD and the other based on the Shaka era which is reckoned to have begun in 78 AD. Although called ‘Shaka’ (rather than ‘Kushana’), this era is supposed by many to correspond with the Kanishka era. Others have tried to match Kanishka with another Indian era, the Vikrama, which began in 58 BC. This seems much too early. On the other hand the latest scholarship, based on numismatic correlations between Kushana and Roman coins, pushes Kanishka’s accession way forward to about 128 AD.

Clearly these variations are significant. Were Kanishka’s dates certain, it might be possible to be a little more dogmatic about his achievements, although the same can hardly be said of his elusive successors. If there has to be a blind summit somewhere along north India’s chronological highway, the second to third centuries AD would seem as good a place as any. Should, however, the controversy be resolved, it could mean whole-scale revision of our understanding of the preceding centuries; upgrading even chronological highways can have dramatic results.

ACROSS THE ROOF OF THE WORLD

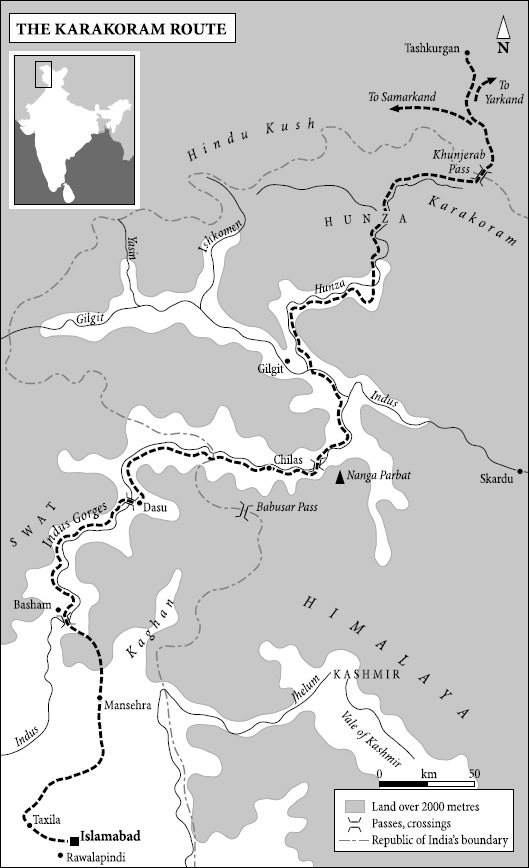

When Pakistani and Chinese engineers began construction of a road link between their two countries in the late 1970s, eyebrows were raised in Delhi and elsewhere. The planned ‘Karakoram Highway’ was seen as evidence of a menacing alignment between Mao-tse Tung’s China and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s Pakistan. As well as being politically sinister and strategically unprecedented, it was thought geographically perverse. For if ever there was a frontier decreed by nature it was the Himalayan chain. This, after all, was India’s Great Wall; behind it the peoples of the subcontinent had traditionally sheltered from the whirlwinds of migration and conquest which ceaselessly swept the arid pastures beyond. Moreover, nowhere was this wall more formidable than at its western bastion where, in the far north of Pakistan, the Great Himalaya becomes entangled in the pinnacles of the Hindu Kush and the glaciers of the mighty Karakoram. Extremes of temperature, colossal natural erosion, frequent seismic activity and recent glacial acceleration also make this the most unstable region on earth. Breaching the rampart with the viaducts, tunnels and easy gradients of an all-weather, two-lane highway looked to be short-sighted, provocative and exceedingly challenging.

Nevertheless, at fearful cost in lives and plant, the road was built. ‘The eighth wonder of the world’ was duly hailed, and convoys of battered trucks and buses began occasionally to emerge at its either end after eventful days of motoring across ‘the roof of the world’. The benefits have been mixed. At five thousand metres above sea-level, the Sino – Pakistan border on the blizzard-swept Khunjerab Pass has witnessed a modest flow of trade but little other intercourse. The road has been more of a boon to the isolated mountain communities of Pakistan’s ‘Northern Areas’, although the discreet charms of their valleys have been prejudiced in the process. Only to archaeologists and historians has the road opened a wholly welcome perspective.

That from India the teachings of the Buddha had originally spread to China via central Asia had long been known. The Han dynasty had opened trade with the West via the so-called Silk Route in the second century BC; the Route ran north of Tibet, on through Sinkiang and then down the Oxus through Bactria to Bukhara, Iran and the Mediterranean. The Han dynasty had also been in diplomatic contact with the Yueh-chi long before the latter, as Kushanas, entered India. Later, when Kushana dominion spread in a great arc from Sinkiang through Afghanistan and across the Indus into India, an obvious India–China conduit was created. Additionally Kanishka had clearly revived Ashoka’s policy of patronising the Buddhist sangha and promoting the spread of Buddhist doctrine. From Chinese sources it was even known that the first Buddhist missionaries to China had set out from India in 65 AD. It was therefore probably under the Parthians or the Kushanas that the monks Dharmaraksa and Kasyapa Matanga had made their way to China, there to found the first monastery and begin their work of preaching and translating the sacred doctrines. In their footsteps would follow the procession of teachers and artists, of icons, texts and relics which over the next three hundred years would nurture the new faith and diffuse new art forms in China and beyond.

Traditionally their route is supposed to have proceeded from Peshawar to Kabul and over the Hindu Kush via Bamiyan, a tight valley above which two gigantic statues of the Buddha were carved high in the vertical cliffs. There they stood for 1500 years until in March 2001 Taliban zealots tested them with anti-tank mines, targeted them with artillery and finally toppled them with dynamite. (Exactly six months later Bamiyan’s twin Buddhas were followed to extinction by New York’s ‘twin towers’; the first outrage inspired the second and has often been attributed to the same agency.) Other remains in Bactria itself still attest the Buddhist presence, and thence north and east across the Pamirs, round the desert of Takla Makan and across Lop Nor a succession of Buddhist sites marks the trail to China. ‘The road is long,’ reported a later Chinese pilgrim who had made the return journey to India; looping laboriously right round that mountain bastion of India’s ‘Great Wall’ it is all of three thousand kilometres. There is no doubt that it was indeed an important route for the traffic of both ideas and commodities; but what the road-builders in the 1970s discovered was that there had been a shorter and better signposted route by way of the upper Indus and Hunza rivers along the line of their Karakoram Highway.

As reconstructed by Dr Ahmad Hasan Dani, Pakistan’s leading archaeologist, the historical trail begins north of Taxila, where the modern highway strikes off into the hills. Suitably enough the first ‘signpost’ is a Kharosthi version of Ashoka’s Major Rock Edict engraved on two badly weathered boulders at Mansehra. The road runs between them and, in view of the incidence of other Ashokan inscriptions at major route intersections, it seems safe to infer that the Indus route into the mountains was in use in the third century BC and here linked with feeder routes from Taxila, Peshawar and Swat. Thence the new road traverses the switchback hills of Kohistan, where innumerable caves and rock drawings continue the Buddhist theme; one drawing is identified by an inscription as being of ‘the monastery of Maharajah Kanishka’. As the roadway wriggles above, and then through, the awesome Indus gorges, more such graffiti on cliffs and rocks – ‘beside the tunnel’, ‘above the petrol station’ – record the passage of individual monks and the presence of stupas and viharas.

West of Chilas, beneath the snowy massif of Nanga Parbat, the Indus valley opens out into a scorching lunar wasteland, devoid of vegetation but garish with rocks of every hue. Here one of many inscriptions mentions the Kushana king Wima Kadphises. Nearer the windswept little town a scene etched on a boulder by the river clearly identifies the Shaka king Maues; it is ‘the first proof of the conquest of this region by the Scythian ruler’8 who seems to have actually ‘invaded’ the Panjab by this route. On the other side of Chilas one of many illustrated boulders is known as the Rock of Gondophares; its inscription lauds the Parthian king who was ‘doubting Thomas’s’ patron.

A sculpted Buddha and more stupas lie in the valleys round Gilgit. Thence both highway and Buddhist trail funnel into the Hunza valley for the spectacular climb up to the glaciers. K2 and associated peaks lie to the east with the Khunjerab Pass and the Chinese border dead ahead. The highway terminates at Tashkurgan, an ancient staging post on the main Silk Route. As a final reminder that this vital trail and all the territory through which it passed lay within the Kushana empire, there is a veritable data-bank of ancient kings, cults and passing strangers, including notices of both the first Kadphises and again of Kusana Devaputra [‘son of God’] Maharajah Kaniska, on the so-called Sacred Rock of Hunza.

The new Karakoram Highway which runs along its southern face … led to the discovery of this monument of world importance that had remained hidden for centuries. The Sacred Rock has stood adamantly through the ravages of time and maintained the carvings and writing of men to tell us about the long-forgotten history of the place and of the pathway along which man travelled from Gandhara to China.9

So the Karakoram Highway, though defying geography, can scarcely be said to have confounded history. In fact it faithfully follows what is now recognised as the preferred route of Buddhist missionaries carrying their teachings to Sinkiang and China.

It is also clear that the teachings in question were increasingly those of Mahayana Buddhism. At the Fourth Buddhist Council held under Kanishka’s auspices a long-simmering dispute within the sangha had led to schism. Those purists who adhered to the essentially ethical content of the Buddha’s teachings became the Hinayana school, while those who would elevate the Buddha and other potentially ‘enlightened ones’ to the status of deities deserving of worship, and so make of his teachings a conventional religion, became the Mahayana. The former persisted in not representing the Buddha as a human figure; in Hinayana art his presence is traditionally indicated merely by a footprint, a throne, a tree, an umbrella. But the Mahayana introduced the Buddha as icon, depicting the ‘enlightened one’ and a host of other Boddhisatvas, together with their female counterparts, in human form. The idea may have come from the imagery of Graeco-Roman gods introduced by the Bactrian Greeks and from the mainly Roman statuary which was evidently much treasured and traded thereafter. Certainly from this coincidence of Mahayanist demand and Mediterranean supply arose the distinctive style and motifs of Gandhara art.

The Kushana, controlling east – west trade in Bactria as well as vast territories in India, had wealth to lavish on both the new faith and the new art; they may even, like Gondophares, have imported western craftsmen like St Thomas. The style developed rapidly, influencing architecture and painting, and inspiring a narrative art based on Buddhist legend but using Graeco-Roman compositions and mannerisms. Exceptionally, the figure of the Buddha himself proved less susceptible to this ‘forum’ decorum; though draped in classical folds and endowed with a serene Grecian countenance, his posture, gestures and physical features conformed strictly to Indo-Buddhist iconography. Such was the Gandhara tradition, a curious synthesis of Kushana patronage, Graeco-Roman forms and Indian inspiration. In sculpture, stucco, engraving and painting, it was this synthesis which passed on up the Karakoram route, or round via Bamiyan and Bactria, to fill the monasteries along the Silk Route and provide the inspiration for later Buddhist art in China and beyond.

The Karakoram trail would be little trodden after the fourth century, when Buddhism in north-west India would be eclipsed by more intruders from central Asia, this time the Huns. Despite those ravages of time and nature, the Karakoram records have therefore remained comparatively undisturbed. Significantly, they reveal little about the route being used for trade. Chinese silks, in particular, were imported into India for re-export from India’s west coast ports to Egypt and Rome. If such caravans avoided the Karakoram route it was presumably because they found the gradients and the grazing of the Bactrian route more agreeable than the cliff-face ladders of Hunza and the landsliding slopes of the Indus gorges. Lacking commercial potential, the Karakoram route was quietly abandoned.

LOOKING OUTWARDS TO THE SEA

Elsewhere the exchange of ideas matched that of commodities stride for stride, stage for stage. In peninsular India – the region south of the Narmada river comprising the Deccan and the extreme south – the last centuries BC and the first AD witnessed those processes of urbanisation and state-formation which had taken place three centuries earlier in the Gangetic region. But here it was trade which stimulated the transition and trade routes which defined it, especially in the western Deccan (Maharashtra and adjacent regions) and in the extreme south (Tamil Nadu and Kerala). Something of that slow metamorphosis from pastoralism and subsistence agriculture to wet rice-cultivation and an agricultural surplus is also discernible. The construction of irrigation works in the south goes back to the second century BC and was accompanied by a demographic shift from upland settlements to the alluvial and easily watered soils of the deltas. ‘In the Chola country, watered by the Kaveri, it was said that the space in which an elephant could lie down produced enough rice to feed seven’ (people, presumably, rather than elephants).10 But here a surplus laboriously realised from agriculture, and then partially squandered on oblations designed to ensure its repetition, was second-best to the surplus on offer from the export of marine and forest produce (especially pearls and pepper) and the re-export of luxury items from further afield. Such options, not open to the Gangetic states, propelled the peninsula from Stone Age to statehood in record time.

Before the first century BC the southern extremity of the subcontinent scarcely features in India’s history. Today’s southern states – Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala – correspond to the languages spoken in each, respectively Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam. All belong to the Dravidian family, which is quite distinct from the Indo-Aryan whence Sanskrit and most of north India’s contemporary languages derive.

Dravidian-speakers are thought to have preceded Indo-Aryan-speakers in the subcontinent. It has yet to be proved that the Harappans’ language was some form of Dravidian, but the survival of a pocket of proto-Dravidian-speakers in Baluchistan, the Pakistan province which borders with Iran, does suggest that the language was in use west of the Indus and could have emanated from there. It also once enjoyed a wide currency in Gujarat and Maharashtra, though whether in the course of a ‘descent’ to the south, or an ‘ascent’ from it, is uncertain. By the mid-first millennium BC, it was certainly well established in the south, perhaps as a result of dissemination by Dravidian-speakers possessed of the horses and iron weaponry usually associated with the Sanskritic arya, or possibly very much earlier as the language of those responsible for the megalithic sites found in upland regions of the peninsular interior.

The four Dravidian languages must have developed from proto-Dravidian at an early stage since they were already distinct from one another in prehistoric times. Each, too, was already confined to the region represented by today’s states. In fact the continuity of such geo-linguistic entities is the outstanding feature of south Indian history. Here, unusually, definable linguistic units seem to predate the states into which they would become integrated.

Megasthenes in around 300 BC knew of the Pandya kingdom; then, as subsequently, it occupied ‘the portion of India which lies southward and extends to the sea’; and it had 365 villages, a not incidental number in that each was expected to supply the needs of the royal household for one day in the year. Ashoka was even better informed. In the Major Rock Edicts he lists his southern neighbours as the Cholas and Pandyas (respectively the northern and southern Tamil-speaking peoples), the Satiyaputras (whose identity is disputed), the Keralaputras (or the Malayalam-speakers of Kerala), and the people of Sri Lanka. Although none formed part of the Mauryan empire, all, according to the Beloved of the Gods, acknowledged the superiority of dhamma and had imitated the Ashokan provision of roadside shade trees and of medical care for men and animals.

Later the all-conquering Kharavela, king of Kalinga (Orissa), also noticed the southern kingdoms. In his one extant inscription he typically pretends to have defeated a confederacy of Tamil states and to have acquired a large quantity of pearls from the Pandyas. Pearls and shells, along with the fine cottons of Madurai, the Pandya capital, are also mentioned in the Arthasastra. There, in a discussion on how to maximise the state’s revenue, Kautilya’s mentor rashly suggests that north India’s most valuable trade is that with central Asia. The know-all brahman puts him right in no uncertain terms: the trade via the Daksinapatha (the ‘Southern Route’) is the more valuable and, besides, the route is very much safer. Thus trade with the south, albeit in prestige goods, was well-established in Mauryan times; and by way of the secure – and, no doubt, well-shaded – Daksinapatha prestigious ideas also travelled down the peninsula.

Of these and much else about the south we know from anthologies of Tamil poetry and from an early Tamil grammar. The poems, of which the oldest date from about the time of Christ, were composed and first recited at marathon arts festivals, or assemblages (sangam), organised by the Pandyan court. They were collected into the ‘Sangam’ anthologies and committed to writing only very much later. Like the Sanskrit classics, they may therefore contain additions and revisions. On the other hand, unlike the Sanskrit classics, they were not the property of a particular caste and served no obvious ritual purpose. Moreover, they provide much reliable detail about social conditions. ‘It would be difficult to make too much of this fact,’ writes an American authority on Sangam literature. ‘Not only does ancient Tamil literature furnish an accurate picture of widely disparate classes; it also describes the social conditions of Tamil Nadu much as it was before the Aryans arrived in the south.’11

This verdict suggests some future Aryan mass-migration, for which the evidence is scant. Besides, Sangam literature was already aware of Aryan and Sanskritic ideals. The Tamil poets – and poetesses – knew the epics well and were keen to associate their patrons with the heroes of the Mahabharata. Place-names like Madurai, a variant of ‘Mathura’, reflect the early adoption of the sacred geography of the epics; and just as ‘Ayodhya’ travelled on to Thailand and central Java, so ‘Mathura/Madurai’ would make a further landfall in the crowded island of Madura off eastern Java. The Sangam poets also knew of the fabled wealth of the Nandas and of the one-time presence of the Mauryas in Karnataka. Brahmans were already well-established in the south and were the recipients of land grants; Buddhism and Jainism were also familiar; and the script used in the Tamil dedications of their caves was a form of north Indian Brahmi.