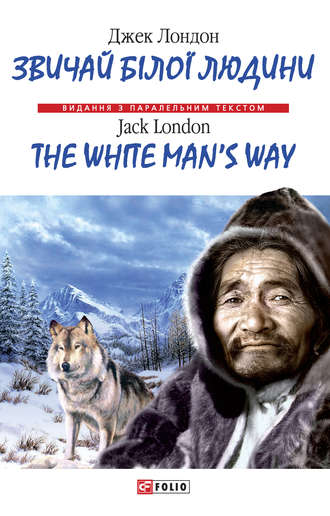

Звичай бiлої людини = The White Man's Way

Полная версия

Звичай бiлої людини = The White Man's Way

Язык: Украинский

Год издания: 1905

Добавлена:

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу