полная версия

полная версияПозитивные изменения, Том 3 №1, 2023. Positive changes. Volume 3, Issue 1 (2023)

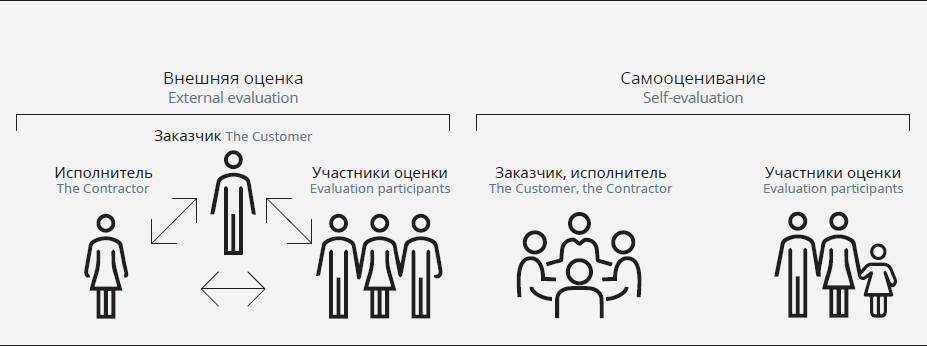

• An evaluator – a specialist hired by the Customer to perform the evaluation.

• Evaluation participants – the people who provide the information for the evaluation; these are usually employees or managers of the programs being evaluated (ASPPE, 2017).

Figure 1. Self-evaluation: three in one

ASPPE suggests that evaluation must be guided by the following principles:

1. Focus on practical use of the results.

2. Competence of the performers.

3. Appropriate methodology.

4. Transparency.

5. Safety.

6. Flexibility.

The “general case,” for which ASPPE principles were developed, is an external evaluation (see Figure 1).

A program (project) self-evaluation is the systematic collection of information about the activities of the program (project), its characteristics and outcomes, which is performed by the program (project) team to make judgments about the program (project), improve the effectiveness of the program (project), and/or inform decisions about future programming. The difference between this definition and the generic definition given at the beginning of the article is all in the italicized text: here, everything is done by the project team itself. The people implementing the project also set the evaluation task, plan the evaluation, collect the data (while also serving as important sources of information), analyze the data, formulate the evaluation results, and use them – all on their own. It turns out that in self-evaluation, the project team acts as the customer, the contractor, and the evaluation participants (see Figure 1).

Do the ASPPE evaluation principles apply in a self-evaluation situation?

We had a series of discussions on this issue as part of the 2022 PROOCENKU Club meetings[32]. They were attended by more than 40 people, mostly coming from non-profit organizations from many regions of Russia.

The outcome of these discussions can be summarized as follows:

1. The evaluation principles proposed by ASPPE are applicable to NGO self-evaluation.

2. Short definitions of these principles also apply to the self-evaluation situation.

3. However, recommendations for the use of these principles in self-evaluation practice require significant adjustment and simplification.

We have developed and discussed guidelines for a self-evaluation situation. This is how the Principles of Self-Evaluation of NGO Programs and Projects have appeared (PROOCENKU Alliance, 2023). These principles, with recommendations for their application, are presented below. I believe it can be useful to any NGO, regardless of its specialization.

Principle 1. Focus on practical use of the results.The whole self-evaluation process should be focused on getting information that is useful to you.

Recommendations:

• You need to be as specific as possible as to why you are doing self-evaluation. Think carefully and discuss the scope of work for self-evaluation. Formulate the questions you want answered, and discuss who will use those answers and how.

• If it is not clear who and how will use the answers to any of the suggested questions, exclude these questions from the scope.

• Include only those questions where answers are not known or at least not obvious to you.

• See if there is a simpler way to answer these questions, rather than performing a self-evaluation.

• Try to keep the number of questions to a minimum. Leave only those of most importance to you.

• At the end of self-evaluation, hold a meeting to discuss the results and plan actions required to use those results (with timelines and responsibilities).

• Think about whether some of the results of your self-evaluation can be useful to someone else besides you.

Principle 2. Competence of the performers.NGO employees who conduct self-evaluation must have the necessary and sufficient knowledge and skills to do so.

Recommendations:

• Self-evaluation is carried out according to certain rules. You don’t have to become an expert evaluator, but you do need to know the basics. To do this, you can read special literature or send some of your employees to a training.

• Keep in mind that it is always possible to consult with experts in areas where your own knowledge and skills are lacking. For example, your local university or professional evaluators association.

• Consider self-evaluation an opportunity to learn through practice. Discuss the experience and learn from it.

Principle 3. Appropriate methodology.The choice of the general approach to self-evaluation and the methods of conducting it should be well justified, considering the limitations. Various evaluation methods must be used, following appropriate procedures and standards.

Recommendations:

• When planning self-evaluation, consider the limitations of available resources and time. Remember that you do not have all the necessary knowledge and skills for evaluation.

• It is important to have an understanding of the strengths and limitations of different approaches to project and program evaluation.

• When choosing self-evaluation methods and tools, it is better to do simple things right than to do complicated things wrong.

• If you have any doubts about the capabilities or appropriateness of a particular tool, you should consult with an expert or refrain from using that tool.

• Remember that the familiarity and prevalence of techniques do not guarantee that they will be appropriate for self-evaluation of a particular project in a given setting.

• Everyone can make mistakes, and it is important to learn from them and avoid their repeating.

Principle 4. Transparency.Self-evaluation is a transparent process: all parties involved must be informed about the goals, methodology and intended use of its results.

Recommendations:

• Make sure that everyone involved in self-evaluation has sufficient information about the process and agrees to provide data voluntarily (respecting the principle of “informed consent”).

• Full results of the self-evaluation are only intended for you. For everyone else, they can either be partially open (at your discretion) or completely closed.

• You need to consider that you may have a bias towards your own project and be suffering from having lost the fresh perception of the project (“blurred view”): these issues should be openly discussed by the self-evaluation participants.

• Since you are performing the self-evaluation for yourself, not for someone else, you are interested in seeing your project for what it is. In this situation, embellishing simply makes no sense. Therefore, you should not view the self-evaluation situation as a potential conflict of interest or be concerned about it.

Principle 5. Safety.Self-evaluation should be conducted with respect for the dignity of all its participants, regardless of their role, social status and individual characteristics. When conducting a self-evaluation, you should consider the possible negative effects it can have on both individuals and organizations. The risk of possible negative consequences should be minimized, and participants in the self-evaluation should be informed about them.

Recommendations:

• Discuss whether or not self-evaluation could result in harming someone. If this is a possibility, even in theory, all participants should be made aware about it.

• Discuss how you can minimize the risk of negative consequences of self-evaluation. Do your best to avoid such consequences.

• Self-evaluation should be conducted when NGO employees are in a resourceful state; that is, when they have enough emotional, physical, mental strength and energy to do so. Participating in self-evaluations is an additional burden for the employees, and this should be considered when planning their work, to avoid burnout.

• Self-evaluations are part of your organization’s activities, so they must be conducted in strict compliance with the ethical standards relevant to your NGO’s scope of work.

Principle 6. Flexibility.It is necessary to provide for the possibility of adapting the self-evaluation methodology to each specific case, as well as to changing conditions.

Recommendations:

• There are many different approaches to evaluating projects and programs. You should choose the one that is best for your project, given the conditions. Even if something has worked well for evaluating your projects in the past, it does not necessarily mean it will work for your current project.

• In the process, be flexible and adjust the plan, methods, and tools of self-evaluation as needed to accommodate changing conditions or newly emerging factors.

• Just in case, check yourself: isn’t the decision to be “flexible” an excuse for not conducting self-evaluation in good faith, and could it lead to negative consequences?

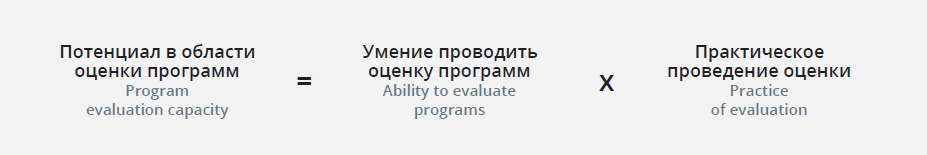

PRINCIPLES OF SELF-EVALUATION AND CAPACITY BUILDING IN EVALUATIONSelf-evaluation involves building one’s capacity for evaluation. In this regard, it may be useful for NGOs to keep in mind the following “formula” (Kuzmin, 2009):

According to this “formula,” if you know how to do an evaluation but don’t do it, the capacity is zero. Similarly, if you do an evaluation but don’t know how to do it, the result is still zero.

In other words, capacity development in evaluation involves balancing two interrelated tasks: one must both learn and apply the knowledge and skills gained in practice. The principles of self-evaluation take both factors into account.

REFERENCES1. Baron, M. E. (2011). Designing internal evaluation for a small organization with limited resources. Internal evaluation in the 21st century. New Directions for Evaluation, 132, 87–99.

2. Gargani, J. (2012). The future of evaluation: 10 predictions. Retrieved from: https://evalblog.com/2012/01/30/the-future-of-evaluation-10-predictions/

3. House, E. R. (1986). Internal Evaluation.

Evaluation Practice, 7(1), 63–64. Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ abs/10.1177/109821408600700105.

4. Kuzmin, A. (2009). Use of evaluation training in evaluation capacity building. In M. Segone (Ed.), From policies to results: Developing capacities for country monitoring and evaluation systems. New York: UNICEF.

5. Kuzmin, A., Karimov, A., Borovykh, A., Abdykadyrova, A., Efendiev, D., Greshnova, E…. Balakirev, V. (2007). Program Evaluation Development in the Newly Independent States. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 4(7), 84–91. Retrieved from: https://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/view/14/29.

6. Love, A. J. (1983). The organizational context and the development of internal evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 20, 5–22.

7. Love, A. J. (1991). Internal Evaluation: Building Organizations from Within: SAGE Publications.

8. McClintock, C. (1983). Internal Evaluation: The New Challenge. American Journal of Evaluation, 4, 61–62.

9. Patton, M. Q. (2008). Utilization-focused evaluation (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

10. Rogers, A., McCoy, A., & Kelly, L. M. (2019). Evaluation Literacy: Perspectives of Internal Evaluators in Non-Government Organizations Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation / La Revue canadienne d’évaluation de programme, 34(1), 1–20. Retrieved from: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjpe/article/view/42190.

11. Volkov, B. B. (2011). Internal evaluation a quarter-century later: A conversation with Arnold J. Love. New Directions for Evaluation (132), 5–12.

12. Volkov, B. B., & Baron, M. E. (2011). Issues in internal evaluation: Implications for practice, training, and research. In B. B. Volkov & M. E. Baron (Eds.), Internal evaluation in the 21st century. New Directions for Evaluation. (Vol. 132, pp. 101–111).

13. Альянс PROОЦЕНКУ. (2023). Принципы самооценивания программ и проектов в НКО. Режим доступа: https://www.processconsulting.ru/attach_files/menu_21_12_22_19.pdf. PROOCENKU Alliance (2023). Principles of self-evaluation of NGO programs and projects. Retrieved from: https://www.processconsulting.ru/attach_files/menu_21_12_22_19.pdf.

14. АСОПП. (2017). Принципы оценки программ и политик. (05.02.2023). Режим доступа: https://eval.ru/attach_files/file_menu_78.pdf. ASPPE. (2017). Principles of program and policy evaluation. (05.02.2023). Retrieved from: https://eval.ru/attach_files/file_menu_78.pdf.

15. Кузьмин, А. И. (2016). Будущее оценки. Режим доступа: https://evaluationconsulting.blogspot.com/2016/06/blog-post_14.html. Kuzmin, A. I. (2016). The Future of Evaluation. Retrieved from: https://evaluationconsulting.blogspot.com/2016/06/blog-post_14.html.

16. Кузьмин, А. И. (2020). История развития мониторинга и оценки в Сети СЦПОИ. Начало. Режим доступа: https://evaluationconsulting.blogspot.com/2020/04/blog-post.html. Kuzmin, A. I. (2020). History of the development of monitoring and evaluation in the SCISC Network. Beginning. Retrieved from: https://evaluationconsulting.blogspot.com/2020/04/blog-post.html.

Союз дела и денег. Оценка экономической устойчивости проектов в области социального предпринимательства

Елена Авраменко

DOI 10.55140/2782–5817–2023–3–1–44–57

Осенью 2022 года по заказу Фонда поддержки социальных проектов была разработана модель оценки воздействия проектов в области социального предпринимательства. Экспертная группа авторов модели из представителей Фабрики позитивных изменений, фонда «Глэдвэй» и других организаций предложила включить в нее компонент «экономическая устойчивость», наряду с «социальным воздействием» и «актуальностью решаемой проблемы». В апробации модели приняли участие 10 социальных предприятий. В этом материале мы расскажем суть оценки экономической устойчивости проектов, предложенной в рамках разработанной модели, и почему методика ее проведения является подспорьем для выработки верных решений.

Елена Авраменко

Эксперт проекта «Разработка модели оценки социально-экономического воздействия НКО» фонда GLADWAY, мастер Lean 6 Sigma уровня Green Belt

ГАРМОНИЧНЫЙ СОЮЗ

Социальное предпринимательство в идеальном варианте должно представлять собой гармоничный союз эффективного решения важной социальной проблемы и устойчивой бизнес-модели. Организация может управлять изменениями и оказывать положительное воздействие на общество только в случае наличия постоянного и надежного финансового ресурса. В этом свете финансовый анализ собственной коммерческой деятельности является одной из составляющих успеха. Рассматривая динамику финансовых показателей от года к году, предприятие понимает слабые и сильные стороны управления, а значит может планировать и улучшать показатели с течением времени. Именно поэтому эксперты решили добавить в разрабатываемую модель показатель экономической устойчивости.

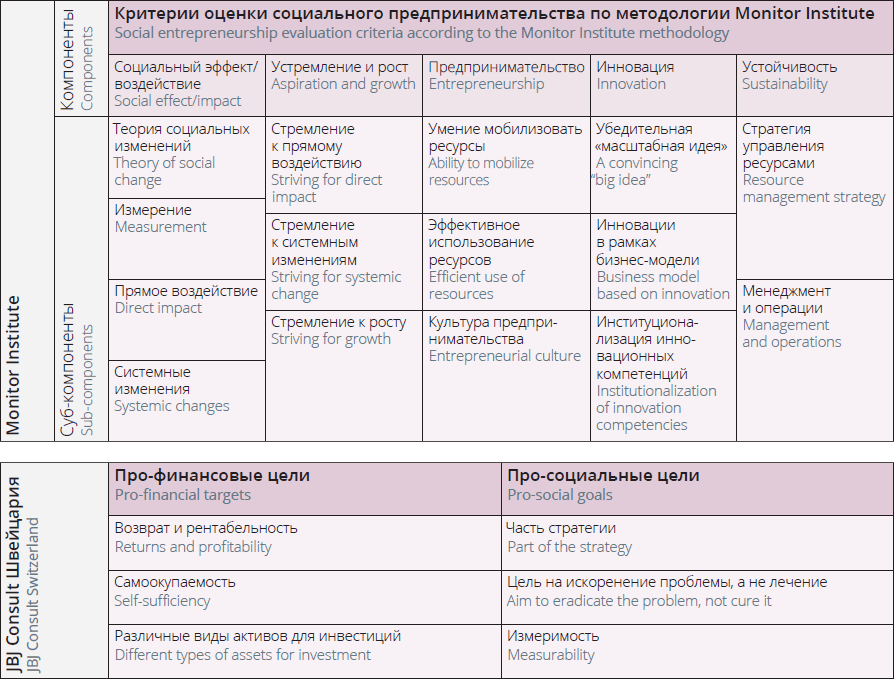

Необходимость оценки экономической устойчивости и финансовых показателей деятельности организации социального предпринимательства подтверждается успешным опытом западных компаний, ведущих консалтинговую деятельность в области социального импакта (см. Рис. 1). Например, оценку рентабельности, самоокупаемости, возврата инвестиций и других финансовых показателей проводит швейцарская JBJ Consult, ориентированная на то, чтобы бизнес их клиентов приносил и финансовую, и социальную отдачу. Другим примером может служить Monitor Institute by Deloitte, которая работает с организациями социального воздействия и выстраивает их эффективную работу как в области импакта, так и в области управления организацией и ее ресурсами.

Рисунок 1. Использование экономических показателей в оценке социального предпринимательства в западных странах (по данным исследования АНО «Эволюция и Филантропия»)1

* – актуально для институциональных инвесторов, которые хотят для начала реализовать пилот, оценить риск

ТРИ КЛЮЧЕВЫХ ПОКАЗАТЕЛЯ

Расчет показателя экономической устойчивости построен на принципе доступности и однозначности используемых данных: при составлении модели оценки указывались конкретные места в форме бухгалтерского баланса, где можно найти соответствующие показатели. Потому не приходится говорить об экономической составляющей в терминах рисков и в контексте инвестиций, как это предлагается в SROI и IMP. Эти методологии требуют использования не просто бухгалтерских, но эконометрических методов анализа, которые не доступны для широкого круга социальных предпринимателей. Сфера деятельности большинства проектов социального предпринимательства не требует наличия в штате специалиста по вычислительным методам в экономике и/или по социальным наукам.

Именно поэтому были взяты доступные для оценки показатели, отражающие эффективность экономической составляющей социального предприятия, и которые каждое предприятие может рассчитать без погружения в сложные методы анализа.[33]

В предложенной оценке финансового состояния организации используются коэффициенты текущей ликвидности, финансовой устойчивости и рентабельности, рассчитанные на основании бухгалтерских форм.

1. Текущая ликвидность позволяет определить, достаточно ли у фирмы оборотных средств для своевременного покрытия текущих обязательств.

2. Финансовая устойчивость показывает степень зависимости организации от внешнего финансирования и помогает спрогнозировать ее платежеспособность в долгосрочной перспективе.

3. Рентабельность продаж комплексно отражает степень эффективности использования материальных, трудовых и денежных ресурсов. Снижение этого показателя отражает сокращение объёмов продаж или демонстрирует неэффективность хозяйственной деятельности.

Указанные три показателя были выбраны в методике в качестве ключевых для финансового анализа предприятия, показывающие эффективность экономического управления в нескольких плоскостях. Текущая ликвидность показывает финансовую надежность и устойчивость на коротком горизонте (способность платить по счетам в течение года). Коэффициент финансовой устойчивости показывает структуру капитала – этот показатель характеризует долгосрочную финансовую надежность и способность оплачивать свои обязательства в длительном периоде. Важно, чтобы социальное предприятие не было «закредитованным». Рентабельность продаж показывает управленческую эффективность, правильность оценки доходов и расходов и их контроль.

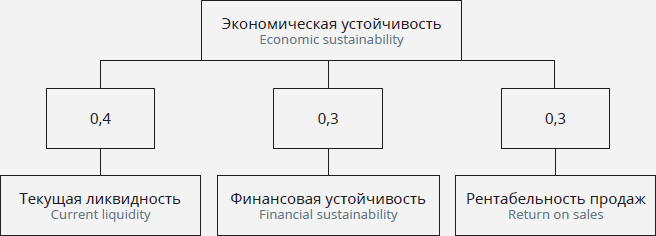

Влияние каждого показателя на итоговую оценку происходит с учетом присвоенного веса (см. Рис. 2):

Текущая ликвидность – 0,4;

Финансовая устойчивость – 0,3;

Рентабельность продаж – 0,3.

Рисунок 2. Веса показателей при расчете экономической устойчивости

Коэффициенты весов между тремя показателями близки, но больший коэффициент присвоен текущей ликвидности. При нормативном уровне коэффициента текущей ликвидности организация имеет надежное финансовое положение в текущем году, и, следовательно, может за год улучшить два других показателя. Если же в текущем году организация не может покрыть собственные обязательства, то перспектива долгосрочной надежности и эффективное распределение текущих доходов и расходов не будут полноценной гарантией закрытия рисков банкротства.

Итоговая формула показателя экономической устойчивости имеет в качестве показателя индекс, который получается как взвешенная сумма показателей текущей ликвидности, финансовой устойчивости и рентабельности продаж по формуле:

Экономическая устойчивость = 0,4 * Текущая ликвидность + 0,3 * Финансовая устойчивость + 0,3 * Рентабельность продаж

ФОРМУЛЫ И ОПРЕДЕЛЕНИЯ ПОКАЗАТЕЛЕЙ1. Текущая ликвидность (Ктл) – отношение стоимости краткосрочных активов (Акр) к стоимости краткосрочных обязательств (ОБкр) социального предприятия.

Ктл = Акр / ОБкр

Краткосрочные активы (Акр) – это имущество компании, дебиторская задолженность и другие объекты, которые участвуют в создании дохода: например, деньги на счетах и в кассе, дебиторская задолженность, запасы, сырье, вклады в банках, акции и облигации других компаний. Краткосрочные активы потребляются или реализуются в период менее года.

В форме бухгалтерского баланса краткосрочные активы отражаются по следующим строкам (см. Таблица 1).

Таблица 1. Виды оборотных активов в форме бухгалтерского баланса

Краткосрочные обязательства (ОБкр) – это долговые обязательства предприятия со сроком погашения до одного года. Краткосрочные обязательства организации включают в себя: кредиторскую задолженность (краткосрочные займы, необходимые для оплаты поставщикам за поставку товара, покупателям при производстве по предоплате, другим кредиторам), краткосрочные банковские кредиты, задолженность по налогам и заработной плате.

В форме бухгалтерского баланса краткосрочные обязательства отражаются по следующим строкам (см. Таблица 2).

Таблица 2. Краткосрочные виды обязательств в форме бухгалтерского баланса

Суть коэффициента текущей ликвидности состоит в том, что он позволяет определить, достаточно ли у фирмы оборотных средств для своевременного покрытия текущих обязательств. Платежеспособность фирмы оценивается с помощью Ктл.

НОРМАТИВНЫЕ ПОКАЗАТЕЛИ:

Нормативное оптимальное значение Ктл находится в границах от 1,5 до 2,5 в зависимости от отрасли. Коэффициент текущей ликвидности более 3 говорит о нерациональной структуре капитала, о замедлении оборачиваемости средств, вложенных в запасы.

2. Финансовая устойчивость (Кфу) – отношение собственного капитала (Ск) к сумме обязательств по привлеченным средствам (Зср).

Кфу = Ск / Зср

Собственный капитал (Ск) – это стоимость всего неденежного и денежного имущества, принадлежащего предприятию, за вычетом стоимости всех его непогашенных обязательств.

Для расчета собственного капитала часто используют простой метод: берут итог строки 1300 бухгалтерского баланса.

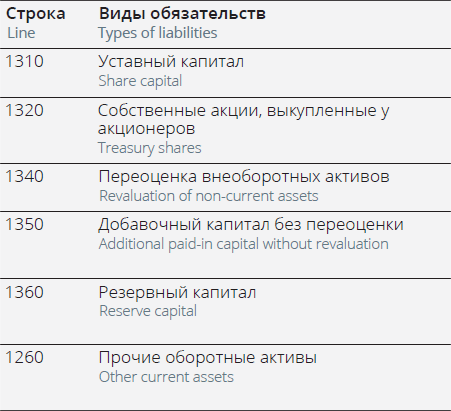

Детально собственный капитал в бухгалтерском балансе отображается по следующим строкам (см. Таблица 3).

Таблица 3. Собственный капитал в бухгалтерском балансе

Заемные средства (Зср) – это имущество и деньги сторонних лиц, привлеченные предприятием на определенный срок для использования в своей деятельности, условие привлечения заемных средств – это начисление процентов по ним.

В бухгалтерском балансе организации для отражения заемных средств предусмотрены 2 строки: строка 1410 «Заемные средства» и одноименная строка 1510.

Суть коэффициента финансовой устойчивости состоит в том, что он показывает степень зависимости организации от внешнего финансирования и помогает спрогнозировать ее платежеспособность в долгосрочной перспективе.

НОРМАТИВНЫЕ ЗНАЧЕНИЯ:Нормативным значением для коэффициента считается диапазон выше 0,8.

3. Рентабельность продаж (Крп) – отношение прибыли (Пр) к выручке (Врч) от продаж. Для перевода в проценты необходимо умножить на 100.

Крп = Пр / Врч * 100 %

Прибыль (Пр) – положительная разница между суммарными доходами (в которые входит выручка от реализации товаров и услуг, полученные штрафы и компенсации, процентные доходы и т. п.) и затратами на производство или приобретение, хранение, транспортировку, сбыт этих товаров и услуг. Прибыль = Доходы – Затраты (в денежном выражении).