‘We’ll look after him this afternoon,’ he announced. ‘We’ve promised to take him to the Mourne Mountains. And we’ll put him on board the boat tonight. Don’t you worry about him any more.’

‘We’re not going to,’ Jack returned drily.

It was then that Pam remembered that Jack was crossing by the same steamer.

‘He’s going by Liverpool, isn’t he?’ she asked Ferris.

‘Yes, by Liverpool.’

‘So are you,’ she turned to Jack.

‘By Jove, so I am! I forgot that for the moment.’

‘Oh?’ said Ferris with a sharp glance. ‘You’re crossing tonight, are you?’

‘Yes: I’ve a legal appointment in London on Monday morning.’

‘Change your route and go by Heysham,’ Pam suggested.

‘Not I,’ Jack answered. ‘Do you think I’m going to have my plans upset by that wretched fish? Besides I’ve engaged my berth.’

‘Well, you won’t want to see him on the journey, I expect!’

‘I’ll not see him. I’ll go in latish and go to bed when I get on board.’

Ferris nodded. ‘Sorry about this. I suppose there’s no use in my offering you a lift?’

‘No,’ said Pam. ‘I’ll drive him in. That is, Jack, if you’ll let me have the car.’

‘Will you? Good girl. You hear that?’ he looked at Ferris.

‘Right,’ said Ferris as they parted.

The boat left at eleven on Saturdays, and Pam arranged to go round to the Penroses’ after dinner, so that they might start when they felt inclined. ‘About quarter to ten, I suggest,’ Jack said. ‘Then you’ll be back about half-past. Not too late for you? Because you have to walk home.’

‘Of course not: don’t be silly.’

This programme they carried out, but not in its entirety. One unexpected factor slightly upset their plans. When at quarter to ten they went out to the car, they found that one of the tyres was flat.

‘Curse it,’ Jack growled. ‘It’s a back wheel and it’s the very mischief to get a jack in under the axle with all this overhang of luggage carrier and so on behind. And there’s no room to work here. We’ll have to push it out and chance cutting the tube.’

‘Will you have time? Would it not be better to ring up for a taxi?’

‘Might be long enough before we’d get one at this time of night. No, we’ll be all right if you’ll lend a hand.’

It was a small job to change the wheel, but it took a good deal more time than they had expected. Pulling the car out of the garage and getting it jacked up by the light of torches proved no joke, and to make matters worse about ten o’clock it began to rain. Before they had finished Jack wished he had taken Pam’s advice and rung for a taxi. Then he found himself hot and dirty and he had to take further time to wash and change. Instead of getting away about quarter to ten, it was nearer half-past when they started.

As the day passed Pam had grown more and more to regret that Platt’s visit had been marred by the morning’s unfortunate little incident. Particularly she was sorry that the relations between Jack and Platt had become so strained. If the deal went through, as she now expected it would, they would have further dealings with the man, and it would be a thousand pities if there should be continued friction. Besides on general grounds she hated an atmosphere of ill feeling.

‘Jack,’ she said suddenly as they turned out of York Street towards the Liverpool berth, ‘I want you to do something for me. Will you?’

‘What is it, old thing?’

‘No: you must promise first. It’s a very little thing and you can do it easily. Will you—to please me?’

‘It must be something rotten if you make such a song about it.’

‘It’s not, I assure you. If you don’t, I’ll be really hurt. Do promise, Jack.’

‘Oh, all right. What is it?’

‘You do promise?’

‘I do promise.’

‘I want you to make friends with Platt.’

Jack frowned. ‘I never want to see the blighter again.’

‘But that’s just it. We’ve got to work with him and we don’t want everything spoiled by friction. Besides, I don’t like it. Go to him on board and ask him to have a drink. You needn’t say anything about what’s happened and you needn’t spend any time with him. It’s just to show him that the thing’s over and forgotten.’

‘It’s not forgotten so far as I’m concerned.’

‘But it must be. As I said, if you won’t do this for me, I’ll be really hurt. Besides you’ve promised.’

‘Oh, all right; I’ll do it. But it seems to me you’re making an unholy fuss about nothing.’

‘I’m not. You know perfectly well I’m in the right.’

Further discussion was cut short by their arrival at the boat. They had cut it fine and there was only five minutes to spare. Pam set Jack down outside the Liverpool shed and drove quickly back.

She was glad Jack was going to make peace, even though the unpleasant little episode was such a trifle. The really great thing was that Platt had been convinced as to their claims about the inert petrol. The next step would undoubtedly be that the managing director and his technical experts would come over and a firm agreement would be signed. Then all their work and stress would be over. Money would soon begin to pour in, and what mattered more than anything else, her marriage could take place at once. Oh, how utterly glorious that would be! Pam pressed the accelerator in her eagerness.

The car bounded forward. Fortunately the road was straight and there was no traffic.

5

As Philip Jefferson Saw It

Precisely at 9.30 on the Monday morning following, Mr Philip Jefferson, senior partner of Messrs Wrenn Jefferson & Co., Ltd., of Carfax Street, Bristol, entered his private room at the works and sat down at his desk.

Jefferson was tall and well built, with a shrewd, thoughtful face and a quiet manner. He was a good business man and he was also a good employer. These terms in their strict meaning are synonymous, because the man who is considerate to his employees gets more out of them. But in the narrow sense they mean two distinct and often contrary policies. Jefferson was both keenly alive to the profits of his firm, and he treated his staff well.

Wrenn Jefferson dealt in oils, at least, mainly in oils. They imported and distributed paraffin and crude oils of various kinds. They did a certain amount of refining, producing lubricating oils of all types from thick green stuff for the sight feed lubricators of locomotives to the transparent, almost watery fluid used by watchmakers. They had a fair sized works at Carfax Street, and a larger depot on the Bristol Channel near Avonmouth. They were in a large way of business, outstanding even among Bristol firms. Their reputation was like that of their senior partner: keen but straight in business, prompt with their customers, just with their employees.

Jefferson began the working day by glancing over his mail, which had been removed from the envelopes by his secretary, Miss Beecher, and left on his desk with the relevant papers attached. On the top was a note in the girl’s own hand to say that the Belfast Steamship Company’s Liverpool office had been on the phone and wanted him to ring them up as soon as possible. ‘That blessed oil,’ thought Jefferson as he laid the memo aside. They had supplied the company with a large consignment of lubricating oil which had not proved up to specification, and negotiations for replacing it were in progress. A very annoying affair it had been and Jefferson feared it would end in a heavy loss. Then there was a letter from the secretary of the Bristol Harbour Board about crude oil for their Diesel engines. That was a satisfactory deal; there was money in it all right. An advice from their representative in New York: one of their tankers had been in collision. There was not much damage done, but she would be delayed in dock for a week or more. Harrison Stoker of Bath were ready for the next lot of petroleum. And so it went on.

Jefferson’s interest quickened as he picked up another letter. Platt wrote from some God-forsaken place in Ireland that he would be back that morning. ‘I have seen the demonstration these people put up,’ he wrote, ‘and I must admit it looks convincing. But until some kind of preliminary agreement was signed they wouldn’t let me see the exact process. Unless there was some extraordinary clever jugglery or something of that kind they can do what they say. At all events they’ve got an inert liquid which undoubtedly has the chemical composition of petrol. I’ll give you all particulars on seeing you on Monday morning, but my recommendation will be to go into the matter further.’

Jefferson sat back, and for a moment gave himself up to dreams. What an amazing story the whole thing was! Of course they had taken Platt in. It couldn’t be true. It was too utterly unlikely. But if it were true … Jefferson swore below his breath. If it were … If it were true it would mean money beyond counting or estimating! These Irish people claimed that the stuff could be rendered inert for a farthing a gallon or less, because it appeared that once the change had been started in a large volume, it would creep on through the whole quantity without further application of power. And they claimed to be able to re-energise it for a little over three farthings a gallon—a halfpenny to cover the installation of the plant on each given car or plane, and a farthing for the current necessary to operate it. One penny a gallon extra for absolute immunity from the fear of fire! The air lines would all use it immediately. Most private drivers would use it. Probably it would become compulsory in buses: probably eventually in all vehicles using a public road. If only it were true! Well, he would get rid of these papers and then he would have Platt in and hear his story.

Jefferson touched his bell. ‘Take these letters, Miss Beecher,’ he said as his pretty secretary entered. He dictated quickly and without hesitating for words. The pile of papers decreased, vanished. Miss Beecher stood up to go.

‘Get the Belfast Steamship Company for me, will you, and then send in Mr Platt.’

The girl withdrew, but reappeared in a few moments. ‘The line’s engaged, Mr Jefferson, and Mr Platt has not come in yet.’

Jefferson nodded. How like Platt! Always unsatisfactory. If he wasn’t his wife’s nephew, he, Jefferson, would have kicked the fellow out long ago. Enjoyed the pleasant air of Ireland, he supposed, and wanted another day or two’s holiday. It was really too bad. After he had been given this specially pleasant and interesting job the man might have bucked up a bit. Jefferson decided there would be some plain speaking when Platt did condescend to put in an appearance.

Platt had always been rather a worry. Even at school he had had a bad reputation. But his mother was Jefferson’s sister-in-law. She was also a widow, and in very poor circumstances, and Jefferson, at his wife’s earnest plea and against his own better judgment, had taken the boy into the business. Platt had not done well. He had not done badly enough to sack, but not well enough to promote. There had, however, been a period in which Jefferson felt that he would have to sack him. The wretched youth had begun gambling at cards and had got badly into debt. But because of his wife and for the sake of the family Jefferson hadn’t sacked him. Instead he had paid up. Platt had had a lesson and so far as Jefferson knew there had been no more high play. And now he had been given this important job, and here he was, disappointing again.

The strange thing was that the man had real ability. He was a thundering good chemist and as clever and ingenious as they are made. But so far his cleverness had not been put to the uses which Jefferson would have liked. He would invent a new method of doing something, if thereby he were saved trouble: but he would make no similar effort for the benefit of the firm.

Jefferson had nothing to reproach himself with in his treatment of the young man. He had offered him a home—again to please his wife and against his own desires. To Jefferson’s secret satisfaction Platt had refused the offer. Not offensively, it was true: he had seemed really to appreciate the kindness and had spoken nicely about it, but he had obviously preferred the freedom of lodgings in Bristol. He was extraordinarily secretive: Jefferson never knew what he did in his free time or who were his friends. Jefferson’s efforts to befriend him were always defeated by the man himself. Jefferson felt he could do no more, that—

His reverie was cut short by his telephone buzzer and Miss Beecher’s voice, ‘You’re through now, Mr Jefferson.’

‘The manager of the Liverpool office of the Belfast Steamship Company speaking,’ came another voice. ‘Is that Mr Phillip Jefferson?’

‘Speaking,’ Jefferson returned.

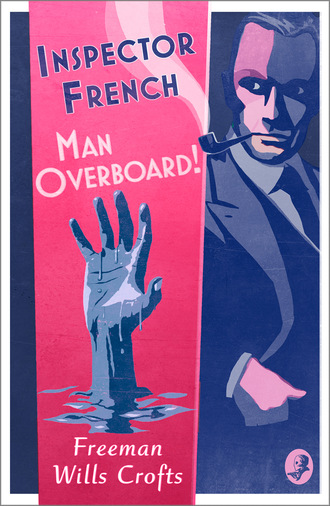

‘I want to ask you if a Mr Reginald Platt is connected with your firm, and if he was crossing here from Belfast on Saturday night?’

‘Yes, to both questions.’

‘Might I ask if Mr Platt has returned to his home?’

‘Not that I know of. He was expected here in the office this morning, but he hasn’t turned up.’

‘Then, Mr Jefferson, I’m afraid I have bad news for you. Mr Platt came on board our steamer at Belfast on Saturday night, but he was not seen at Liverpool.’

‘Not seen?’

‘No sir, I greatly regret to inform you that he is missing. In due course his cabin was opened and his luggage was found there, but there was no trace of himself. From examining the luggage we found your firm’s address.’

This was wholly unexpected news. Jefferson was upset. Surely nothing serious could have happened to Platt?

But his surmisings were cut short by the manager’s voice. ‘We tried to get in touch with you yesterday, but were unable.’

‘I was from home for the weekend and the house was closed.’

‘That explains it. I’m sorry to say that we fear an accident and in duty bound we have informed the police.’

The police!

‘What exactly do you fear,’ Jefferson asked in a somewhat altered voice.

The manager seemed to hesitate. ‘Well,’ he said at last, ‘in such cases there must be the obvious fear that through some accident he has fallen overboard.’

‘Good God!’

‘I wondered if you would be good enough to communicate with his people,’ went on the voice. ‘We couldn’t find any reference to relatives in his papers. I would suggest that perhaps some of his relatives would care to come to Liverpool and see what is being done.’

‘He’s a connection of my own. His mother is my sister-in-law. I’ll probably go myself. I’ll let you know later.’

The manager murmured regrets. He would be glad to see Jefferson and meanwhile everything possible would be done.

As Jefferson replaced the receiver, he felt slightly stunned. Platt, whom he had been expecting to walk into the office any moment, whom he was intending to call over the coals for being late, Platt perhaps was dead! Dreadful!

If the news were true his wife and her sister would take it hard. Not though either of them had seen so much of the young man in the recent past. Still he was nephew to one and son to the other. If he were dead his faults would be forgotten, his good points remembered. And rightly so.

Jefferson reached for a Bradshaw. He would go to Liverpool. Even if he had not wished to do so for his own peace of mind, he would have had to for the sake of his wife and sister-in-law. He wondered if his sister-in-law would want to go too. Far better for her not to, if only she would be satisfied to remain at home. She lived at Gloucester and if necessary he could pick her up on his way.

Then he thought the best thing to do would be to tell his wife at once and let her go to Gloucester and stay with her sister. He would go to Liverpool and keep them advised by telephone of what was being done. Mrs Platt was not on the telephone, but his wife could stay at an hotel and so remain within call. By letting his wife break the news it would be easier for Margery Platt, and the question of her going to Liverpool would not arise.

As these thoughts passed through his mind, he was turning over the pages of Bradshaw. There was a train from Bristol at twelve-twenty, which got in at five twenty-three. That would suit. He rang for Miss Beecher and Lewis, his assistant manager.

‘I’ve had rather disturbing news,’ he said when they appeared, and he repeated what the steamship company’s manager had said. ‘I’m afraid I shall have to go to Liverpool at once. Will you just carry on. I think you’d better put off that shopmen’s deputation, but you can handle everything else.’

Both were obviously thrilled, but though they expressed a dutiful sympathy, he could see that neither had cared for Platt. They were interested in the dramatic side of the affair, not in the man’s possible fate.

‘Well,’ said Jefferson, ‘I’ll be off. I want to go home and tell my wife before getting the train.’

He broke the news to Mrs Jefferson and then drove on to Platt’s rooms and saw the man’s landlady. But Mrs Russell could tell him nothing. Platt had sent her a card from Ireland saying that he expected to be back on Sunday night, but he hadn’t turned up. She could not think what had kept him.

After sending wires to the steamship company’s manager in Liverpool and to Mrs Platt, Jefferson and his wife left Bristol. At Gloucester Mrs Jefferson got out and Jefferson went on alone.

He scarcely realised it himself, but he had come to believe that Platt was dead. Though he did not see how on a calm night anyone could fall overboard from a cross Channel boat unknown to others on board, he supposed that in some way the accident had happened. The only other alternative, suicide, was unthinkable. Platt had no motive. Though perhaps not a favourite at the works, he had a comfortable enough billet there and was decently treated. The man had quite a good time, and excellent prospects, if only he would make an effort to embrace his good fortune.

All the same Jefferson began to wonder whether he himself had been at all lacking in his duty towards his nephew by marriage. The youth had been irritating enough at times, and Jefferson had never hidden his opinion of him. On the other hand he had treated him better than would most employers. No he could not see that he had been in any way to blame. If he had come short in what he might have done, it was because Platt himself was too secretive and distant in his manner to permit of anything else.

In due course Jefferson reached Liverpool and a few minutes later was shown into the manager’s office. Mr M‘Kinstry was a tall raw-boned Ulsterman whose manner was forceful and direct, but behind whose shrewd expression a real kindliness peeped out. He wrung Jefferson’s hand in a powerful grip and asked him to be seated.

‘I was sorry for having to send you bad news, Mr Jefferson,’ he began, ‘but you were the only person whose name we could find. But we didn’t know then that you were a relative of Mr Platt’s. The letter we found was from you as head of the firm, not as his—uncle, I think you said?’

‘Uncle by marriage.’

‘Uncle by marriage, is it? Well I’ll tell you just what we know and then you’ll be able to judge the position.’

‘Thank you; I wish you would.’

‘Mr Platt left Belfast on Saturday night by our motor ship Ulster Sovereign. He was travelling on the return half of a third on rail and first on boat ticket. The purser records the numbers of all through tickets, so that our company may get its share of the fare. There was one for Bristol, and this may have been Mr Platt’s. Mr Platt had written two days before to our Belfast office to reserve a single berth cabin for the Saturday. There was an excess on this, which he paid to the purser.

‘In accordance with our custom Mr Platt was given the number of his cabin and he showed his ticket and berth card to his cabin steward. The steward remembers him well and says Mr Platt told him he did not require any tea in the morning, or to be specially called.’

Jefferson nodded.

‘The check of our passengers,’ continued Mr M‘Kinstry, ‘is not like that on the Southern lines to France. We make it on embarkation: that is, no one can go on board our ships without a ticket. There is no absolute check of travellers leaving the ship. At the same time, as you can guess,’ a certain dryness crept into the manager’s tones, ‘it is usual for the cabin stewards to see those whom they have attended before they go ashore.

‘Now when the boat berthed at Liverpool there was the usual watch over the passengers. Mr Platt was not seen. When it was nearly time for the bus to leave for the stations his cabin steward went to his cabin to remind him of the time. Mr Platt was not there. His berth had not been slept in. But his luggage was there, unpacked.’

‘You surprise me. His berth had not been slept in?’

‘No, and I’m afraid that’s one of the worst features of the affair. If he wasn’t in his berth during the night, where was he? I mean he’d certainly have been seen about the ship—if he had been on board. But no one saw him.’

‘Could he have gone ashore at Belfast for some reason and been left behind?’

‘I’m afraid not. As I said, a careful check on the passengers is made at Belfast. The man who was on the job has been questioned, and he states positively that every-one who went aboard the ship with a through ticket sailed.’

Jefferson nodded. The more he heard of the story, the worse it looked.

‘It is of course possible, though unlikely, that he reached Liverpool and went ashore unnoticed. As I’ve said, there’s not the same systematic check on disembarking. But in this case his berth surely would have been slept in, and his luggage would have disappeared.’

‘It would seem so,’ Jefferson answered unwillingly. ‘Well, then, what did you do?’

‘The cabin steward reported to the purser and a search was made of the ship. Then the captain was informed and a more complete search was made. At last I heard of it. They rang me up at my home. I came up and had a chat with the men, and decided I must inform the police. An inspector was sent over and he searched Mr Platt’s luggage and found a letter to him on your firm’s paper and signed by you. We then tried to get in touch with you, but failed till this morning.’

‘I know. We were away and the servants had gone home. And that’s all that is known?’

‘That’s all, I’m afraid. The thing was kept out of the papers this morning, but it’ll be in the evening ones.’

For some time Jefferson continued discussing the the affair, but without learning anything fresh. If Platt had not gone ashore in Belfast and been left behind—and it was difficult to see either why he should have done so, or if he had, why he should not have wired the fact—it looked increasingly like as if in some unknown and mysterious way he had fallen overboard shortly after the start. But how such an accident could occur was very far from clear.

‘I think I’ll go to the police station and hear what they have to say,’ Jefferson decided, which course M‘Kinstry warmly advocated.

But when a few minutes later he was sitting in the superintendent’s office he soon found that the officer’s object was to obtain information, not to impart it. Superintendent Shepherd was extremely polite, but as close as a clam. They were looking into the matter, yes, but unfortunately they had as yet nothing to report. Mr Jefferson might rest assured that every possible step would be taken to clear the affair up, but so far there had not been time to ascertain all the facts.

But in the meantime Mr Jefferson could help their efforts by answering a few questions. He, the superintendent, presumed that Mr Jefferson would have no objection to that?

Mr Jefferson, on the contrary, was only too anxious to assist.

Then would Mr Jefferson please tell him—and an interrogation of extraordinary completeness followed. Who was Platt? What relation was he to Jefferson? What was his history? Was he a member of the firm? What position did he hold? First came questions whose answers gave a sort of general Who’s Who of all concerned.