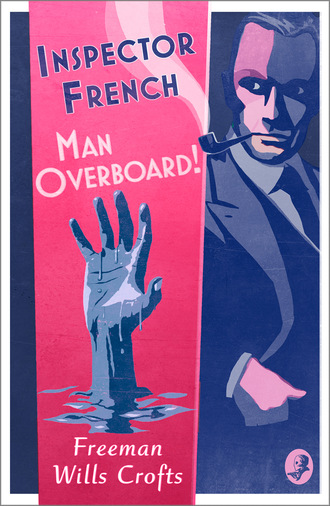

INSPECTOR FRENCH: MAN OVERBOARD!

Freeman Wills Crofts

Copyright

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain for the Crime Club

by Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1936

Copyright © Estate of Freeman Wills Crofts 1936

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008393168

Ebook Edition © June 2020 ISBN: 9780008393168

Version: 2020-05-18

Epigraph

While in no sense a sequel, this book might be called a companion to my Sir John Magill’s Last Journey. It dealt with one approach to Northern Ireland, this with another.

F. W. C.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

1. As Pamela Grey Saw It

2. As Pamela Grey Saw It

3. As Pamela Grey Saw It

4. As Pamela Grey Saw It

5. As Philip Jefferson Saw It

6. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

7. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

8. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

9. As Pamela Grey Saw It

10. As Detective-Sergeant M‘Clung Saw It

11. As Philip Jefferson Saw It

12. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

13. As Detective-Sergeant M‘Clung Saw It

14. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

15. As Pamela Grey Saw It

16. As Pamela Grey Saw It

17. As Pamela Grey Saw It

18. As Pamela Grey Saw It

19. As Pamela Grey Saw It

20. As Pamela Grey Saw It

21. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

22. As Chief Inspector French Saw It

Keep Reading …

Footnotes

About the Author

Also in this series

About the Publisher

1

As Pamela Grey Saw It

From the drive outside Pam’s window there came a sudden crunching of car wheels on gravel, the squeak of a too forcibly applied brake, and a toot—in code—on the horn.

Pam started up, called ‘Coming!’ through the open window, glanced hastily at herself in the crooked little wooden mirror, hurriedly smoothed an errant curl, and ran down the steep winding stairs and through the narrow hall to the car standing in front of the door.

Though her expression had not indicated what she thought of her reflection, she had every reason to be satisfied with it. Pam was not exactly pretty, and she was not beautiful at all. All the same she was a sight to gladden tired eyes. The overwhelming impression she gave was of what used to be called wholesome. She was young, little more than twenty, with a small, finely formed body and movements graceful as a faun’s. In her face there was character; intelligence in the broad forehead and the grey eyes which looked so steadfastly out on the world, a fastidious humour in the small mouth with its delicately twisted lips, strength in the firmly rounded chin. The glow of health shone in her creamy complexion and her expression radiated good humour and the joy of life.

At that moment indeed Pam was looking her best. An eager excitement had brought colour to her cheeks and a flash to her eyes. It was evident that something thrilling as well as delightful was about to happen.

One cause, though by no means the chief, was that waiting for her in the car was her fiancé, Jack Penrose. For a year or more they had been engaged. At first it had looked as if marriage was very far off. Jack was not yet earning anything like enough to set up house on, and Pam’s people were poor and could allow her nothing. But Jack’s prospects were good and the couple had perforce to wait.

Jack Penrose, tall, fair and typically Nordic, was a budding solicitor. At present he was a clerk in his father’s office in the neighbouring town of Lisburn, but he was soon to be taken into partnership and then a marriage would be arranged. Old Mr Penrose’s business was prosperous enough, and there would be sufficient for the moderate establishment the two young people wanted.

All this had been the idea at the time of the engagement, but recently a wonderful vista had opened out before them, a vista so marvellous that at first it seemed wholly incredible. Indeed even now it still appeared infinitely too good to be true. Suddenly and unexpectedly there had come a promise of money. Not a little money—not even a competence. What was dazzling their bewildered gaze was the prospect of a vast fortune: wealth almost infinite: utterly beyond ordinary limits: staggering in its magnitude. And now the journey they were about to take would bring that wealth appreciably nearer.

Pam climbed into the rather elderly Vauxhall. ‘When did you hear?’ she asked as Primrose let in his clutch.

‘Rang up half an hour ago. Said he was ready any time, but I couldn’t get away before.’

‘What did he sound like?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Can’t tell much about a chap from half a dozen words on the telephone.’

‘Oh, yes, you can! What did he say?’

‘Why just that: he’d done his other business and could come down when I was ready.’

‘Sounds all right if that was the way he put it.’ She paused, and then gave an ecstatic little wriggle. ‘Oh, Jack, I’m so excited! I shall simply faint when I see him!’

‘Nice way for an engaged young woman to talk about a strange man.’

‘I’ll just throw myself at him. I’ll make love to him without stopping, all the time he’s here.’

‘If I see you as much as throw an eye in his direction I’ll cut both your throats.’

‘To think of all that’s happened in the last six months! Isn’t it just incredible? There we were and not a bean anywhere. And now! I can’t believe it even now.’

‘Haven’t got it yet.’

‘Fancy enough money to do anything we want! Just fancy! Anything!’

‘Only money? What about a spot of matrimony?’

‘Money of course! You don’t imagine you matter, do you?’

Pam was intoxicated with the amazing prospect of wealth. But Pam could not foresee the future. She didn’t realise that very often Fate offers her benefactions with her tongue in her cheek. They come as promised, but not alone. Some ingredient is added which robs them of their value. Pam didn’t know that a day was coming—was even then on them—when she would have given everything she had if only she had never heard of the fortune or of any person or thing connected with it. She didn’t know that instead of bringing joy and freedom to herself and Jack, the whole affair should grow into a ghastly horror whose memories threatened to stay with them during every remaining moment of their lives.

Jack Penrose and Pamela Grey lived in the little town of Hillsborough in the County of Down, that county which forms the south-eastern corner of Northern Ireland. It is scarcely a town as the word is understood in England, being little more than a collection of grey slate-covered houses fronting both sides of a single steeply falling street, with the church in the middle and the castle at the top. But though small, it is a town of honour in the province, for in the castle lives no less a personage than the Governor—or lived, till a recent fire necessitated his removal. Its street moreover is no mere village street; it is part of the main highway from Belfast to Dublin, and though the unhappy division of the country has reduced the flow of traffic between the two cities, Hillsborough still rumbles by day and night with cars and buses and great lorries grinding their way north or south.

Hillsborough is some dozen miles from Belfast, to which city Jack and Pam were now bound. The road is good, comparatively straight and level, broad and with an excellent surface. At that time, five o’clock in the afternoon, traffic was not heavy, the evening homeward rush having scarcely started. Jack made good speed and they expected to pick up their visitor and be back at Hillsborough well within the hour.

It was early in September and had been a day of gorgeous sunshine: if anything too hot. Now as they drove swiftly along Pam subconsciously feasted her eyes on the colours of the great trees beneath which they passed, dark with the full maturity of summer, but not yet beginning to turn to the reds and browns of autumn. The air through the open roof blew cool and pleasant on her face as she thought over the coming meeting or exchanged a word, half chaff, half earnest, with her companion.

How well she remembered that marvellous evening when ‘the affair’ had begun! As Jack threaded through the traffic of the Lisburn Road she pictured again the scene.

It was almost exactly six months earlier, at the end of February. She was sitting with her father and mother after supper, her father reading the paper, her mother knitting silently and herself with a book. She could remember every detail of the scene, her father sitting crosswise in his chair to get the light more directly on his page, the rubbed patches on the old brown velvet jacket he wore in the evenings, his two sticks placed within easy reach of his hand. She could see again the steel grey of the wool her mother was using, the dancing blue flames from the beech log on the fire, the luxurious abandon with which the large tabby lay extended on the hearthrug. And she remembered her own feelings of unrest and expectancy, of disappointment and of hope—not that she would have admitted these to any living soul.

Her worry was that Jack was overdue. He had promised to come in about eight, and it was now getting on towards nine and there was still no sign of him. Some question of amateur theatricals was to be talked over. They were doing The Yeomen of the Guard in aid of local charities, and she and Jack were taking part. The affair required a lot of discussion. Almost every night some point arose which had to be thrashed out. And until now Jack had never failed to turn up to do it.

Nine came and half-past nine, and then Mr Grey went to bed. He had been in the linen business, owning his own mill and being at one time quite well off. But he had met with an accident. His car had been run into by a lorry and he had been left crippled and an invalid. He had had to retire, and as the depression was then beginning, he had not sold his business to much advantage. The slump had played havoc with his investments, and now the family was tightly pressed for money. Had it not been for Mrs Grey they would have fared badly indeed. She took their financial cares on her shoulders and her unfailing cheerfulness made things run comparatively smoothly. She went to help her husband to bed and Pam was left alone.

Annoyed as Pam was by Jack’s defection, she could not refrain from putting down her book and letting her thoughts centre on him. How splendid he really was, so straight and decent, and in spite of his being late tonight, how utterly dependable! Not too brilliantly clever perhaps, but such a dear! He was like a great dog, strong and brave as a lion, though perhaps none the worse for a little gentle suggestion as to the direction his energies should take. Pam smiled dreamily as she told herself that in future she should be the person to provide that suggestion. She could indeed make him do anything she liked, except where his ‘not done’ code was involved: then he could be as pigheaded as anyone. Never mind! She loved him the better for it.

Then at last at nearly ten o’clock came the quick step on the gravel and the ring on the front door bell. Pam had an urge to rush out, snatch open the door and fling her arms round Jack. But she restrained herself, deliberately even sat for a few moments before going to the hall. Jack must not be spoiled. He must make proper explanations and apologies before he could be received into full favour.

But Jack, when at last the door opened, was evidently thinking of neither of the one nor the other. Without ceremony he caught her in his arms and squeezed her to him, then planted a rather hasty kiss on her lips, put her down, and pushed his way in as if taking her joy at seeing him for granted.

‘I thought you were coming at eight o’clock,’ Pam said rather primly.

He brushed the suggestion airily aside. ‘I know. Couldn’t get away. Look here, Pam, I’ve something to tell you. Come out for a walk, will you? I can’t talk here in the hall.’

She looked at him more critically. He was unduly excited. Something had certainly happened.

‘You can come into the sitting room, I suppose?’ she suggested coolly. The apology she considered inadequate.

He looked in and saw it was empty. ‘Yes, I suppose so. Your father gone to bed?’

‘Yes. Is it the costumes? Have they not turned up?’

He made a gesture relegating costumes to the limbo of the forgotten. ‘Of course it’s not the costumes,’ he declared. ‘Costumes!’ he repeated in a voice of ineffable scorn. ‘I’ve got something more interesting to talk about.’

‘You’re very mysterious,’ she said thawing.

‘It’s nothing now,’ he returned as he dropped into Mr Grey’s arm chair and pulled out his cigarette case. ‘But it’s what it might become.’ He held out the case. ‘There seems to be no end to the possibilities.’

‘Incidentally you might mention what you’re talking about.’

‘Isn’t that what I’m doing? I don’t think I told you, but two or three days ago I met M‘Morris. As a rule, you know, I haven’t much use for M‘Morris, but this time he stopped and began to talk. Said he’d just been coming to see me to know whether he could interest me in a scheme that he was pretty much interested in himself and that he wanted some help with. He said if the thing was a success there would be pretty big money in it for all concerned.’

Pam looked doubtful. ‘I never cared much for Ned M‘Morris,’ she declared. ‘What’s the scheme?’

‘Something chemical: I haven’t got the details yet. They think they’ve made some discovery that’ll simply ooze money. But they want to do some more working out first to make sure everything’s O.K.’

‘They?’

‘Yes, M‘Morris and his friend Ferris. I’ve just been seeing them. That’s what kept me.’

‘And what do they want you to do?’

‘Us.’

‘Us?’

‘Yes, it’s you they want particularly. I’m only a cog: you’re the mainspring that everything depends on.’

Pam was getting annoyed. ‘For pity’s sake will you explain the thing so that I’ll know what you’re talking about. What under the sun have I to do with it?’

‘Well, you’re a chemist, aren’t you?’

‘I’ve done some chemistry at Queen’s, if that’s what you mean.’

‘They want a chemist to help with the experiments.’

‘And what are you going to do? You’re no chemist.’

‘I’m to look after the legal side and the correspondence and so on. And I can give a hand with the experiments too if I’m shown what to do.’

Pam gurgled happily. ‘A fat lot of use you’d be. “What’s this muck in this jug? Well, let’s shove in some of this bottle and see what happens,” and the whole thing goes up in the air. I can just see you in a lab.’

‘My legal advice is what is really wanted,’ Jack said with dignity.

This time Pam fairly hooted. ‘They may be fools, but they couldn’t be as bad as that. Go on; tell me some more.’

‘I don’t consider your conversation at all seemly. It’ll have to be dealt with.’

The discussion was interrupted while Jack took his tribute with kisses and Pam retaliated by boxing his ears.

‘You were saying?’ Pam suggested when the interlude was past.

‘They want us to lunch with them tomorrow. At the Station Hotel. They’re doing the thing in style. At this lunch they’ll tell us the whole story. You’ll come, Pam, won’t you? Do be a sport and come.’

‘Of course I’ll come.’

So the fateful meeting was arranged.

Next day shortly after one o’clock Jack called with the car and drove Pam into Belfast to the L.M.S. Station. In the lounge of the hotel two young men awaited them with an air of subdued excitement.

Edward M‘Morris and his friend, whom he introduced as Fred Ferris from the city of Newry, were contrasts in almost every particular. M‘Morris was tall and thin, taciturn and of gloomy disposition: Ferris was short, stout and jolly. M‘Morris was pale with long lank yellow hair and normal though undistinguished features: Ferris was swarthy of skin with thick dark hair and unusual ears, which had small well-formed upper portions and quite disproportionately long lobes. M‘Morris if anything looked rather stupid and was evidently considerably under his friend’s influence: in Ferris’s little black eyes the sharp twinkle indicated a particularly wide awake and dominating mind. Both seemed a trifle ill at ease and were obviously on their best behaviour.

Though M‘Morris had never been a special friend of Pam or Jack, they had known him for years. He lived about a mile from Hillsborough in the direction of Glenavy. He was, like them, a member of several of the local organisations, the tennis and badminton clubs and the dramatic society, and they had met at the houses of mutual friends. He was a technical assistant on the staff of Messrs Currie & M‘Master, the analytical chemists, of Howard Street, Belfast. So much Pam knew, and after what Jack had told her, she was not greatly surprised when Ferris was introduced as another technical assistant in the same firm. He, it came out in the course of conversation, was unmarried and lived in rooms in Belfast.

After cocktails they went in to lunch. The brunt of the conversation fell on Ferris and Jack. M‘Morris had not much to say, and what he did say had rather the effect of bringing the efforts of the others to a standstill. Pam was not quite at her ease. She felt a little distrustful of the whole affair, and she feared she might be let in for something she would dislike.

The business of the meeting was not mentioned till lunch was over and they were sitting over coffee in a corner of the deserted upstairs writing room. Then M‘Morris opened the ball.

‘I told Penrose last night, Miss Grey, that Ferris had made a chemical discovery and we think it is one of the most important made in this century. But I think he could tell you about it better himself, so I suggest he does so.’

‘Lazy pig,’ said Ferris with a slightly deprecating smile and his black eyes snapped with excitement, ‘you might occasionally do something for your keep.’ Then to Pam. ‘Well, if he won’t tell you, Miss Grey, I will. But that’s right, what he says. We’ve made a discovery and we think it’s a very big thing. For the matter of that, we know it’s a very big thing. I don’t want you to think it’s complete, for it isn’t, but if we could complete it, it would be one of the biggest things ever anyone got hold of.’

He paused, watching them shrewdly. Then as neither spoke, he went on.

‘You’ll be thinking I’m putting it on the high side. Well, I’m not, as you’ll see when I tell you what it is. If we could get it properly completed there’d be more money in it than all the lot of us together could handle. More money than we could estimate. A fortune for everyone connected with it. Now see, here’s what we want.’

Again he paused and again neither Jack nor Pam spoke.

‘What we want,’ he continued, ‘is to work at the thing and see if we can’t get it completed. But as things are, we can’t, and you’ll see why easily enough. We’re not millionaires and we’ve got to live on what we earn. We’d like to get some help. We wondered if you, Miss Grey, and Penrose would come into the thing and help us on a share the profits basis?’

‘How could we help you if we did?’ Pam asked.

Ferris looked at M‘Morris as if for inspiration. ‘We thought if we could raise the necessary cash that M‘Morris and I would devote our whole time to the thing,’ he went on. ‘There would be too much for two, and so we wondered if you would agree to work with us. We know of course you’ve done chemistry.’

‘Not enough for that, I’m afraid.’

‘Oh, yes, quite enough. I would fix up a programme of work.’

‘And what about the spot of cash?’ Jack put in.

Again Ferris looked as for help to his silent friend. ‘We think that might be met. We think there might be someone found who would finance us, of course on the share the profits basis. However, let’s leave that for the moment. Might I—eh—ask if you would feel disposed to come in?’

Pam looked at Jack. ‘We couldn’t say, could we, without knowing something more about it?’

‘Ah, sure that has answered my question,’ Ferris interposed swiftly, ‘or anyway I hope it has. Certainly you’d want all details, and it was to give these we suggested this meeting.’

He paused while a waiter came in, glanced about him, and then disappeared with the coffee cups. It was very silent in the room, which they still had to themselves. The bulk of the hotel lay between them and the trains, and on a Saturday afternoon there was little more than an occasional tram passing outside the windows in Whitla Street. Pam glanced at the three men’s expressions; Jack stolidly expectant, M‘Morris anxious rather than sanguine, Ferris, master of himself and the situation and with his eyes twinkling more shrewdly than ever.

Whatever the result of the afternoon’s deliberations, Pam was enjoying herself. Whatever she was to hear, it couldn’t fail to be interesting. And the prospect held out was alluring. She was fond of chemical work, particularly of research, and there was nothing she would have liked better than to join in perfecting some process, particularly if there was a chance of money at the end of it. She hesitated because—she didn’t like to admit it even to herself, but she wondered whether she entirely trusted those two? Ferris’s eye was very sharp, and he was very polite. Almost oily. Was he too polite to be quite wholesome? Then his voice interrupted her thoughts.

‘There’s just one preliminary,’ he was saying with some slight appearance of embarrassment. ‘You’ll understand that the story is confidential. If a whisper got about as to what we’re after, chemists over all the world would be tumbling over each other to forestall us. We’re not wanting to risk that. I’m afraid I’ll have to ask you to keep what I’m telling you to your two selves.’

‘I promise, of course.’

‘Thanks. And you, Penrose?’

‘Wouldn’t think of mentioning it.’

‘Sure I know I needn’t have asked. Still maybe it was as well. Right then, I can go ahead.’

He settled himself more comfortably in his chair and began his story, speaking with a certain amount of gesture and in a way that compelled interest and attention.