Полная версия

The use of accelerators and the phenomena of collisions of elementary particles with high-order energy to generate electrical energy. The «Electron» Project. Monograph

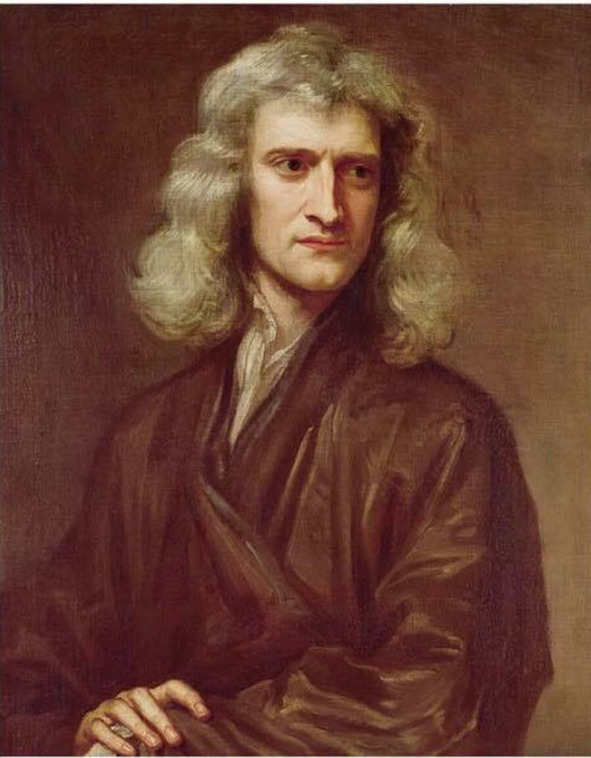

Let us quote Sir Newton himself on this topic from a translation of his works: "It seems to me that from the very beginning God created matter in the form of solid, weighty, impenetrable, mobile particles and that he gave these particles such dimensions, such shape and such other properties and created them in such relative quantities as he needed it was for the purpose for which he created them. These primary particles are absolutely solid: they are immeasurably harder than the bodies that consist of them – so hard that they never wear out and do not break into pieces, because there is no such force that could divide into parts what God himself created inseparable and whole on the first day of creation. Precisely because the particles themselves remain intact and unchanged, they can form bodies that have the same nature and the same structure forever and ever; for if the particles were worn out or broken into pieces, the nature of things depending on them would change. Water and earth, made up of old, worn-out particles and fragments, would differ in structure and properties from water and earth, built from still whole particles at the beginning of creation. Therefore, in order for nature to be durable, all changes in the bodies of nature can consist only in a change of location, in the formation of new combinations and in the movements of these eternal particles… God could create particles of matter with different sizes and can have different shapes, place them at different distances from each other, endow them, perhaps, with different densities and different acting forces. In all this, at least, I do not see any contradictions… So, apparently, all bodies were built from the above-mentioned solid impenetrable particles, which were placed in space on the first day of creation at the direction of God's mind."

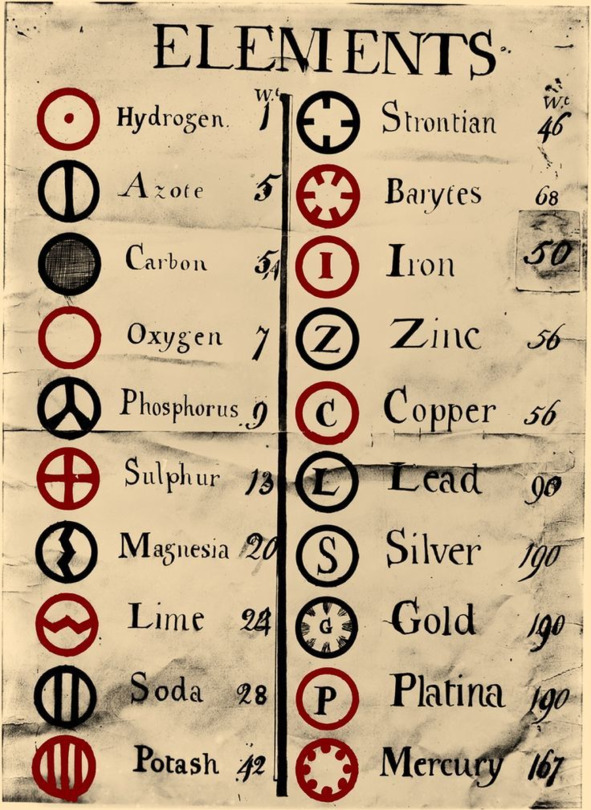

And if at that time Boyle's ideas were established that there are "simple bodies" (chemical elements) and "perfect mixtures" (chemical compounds) and any "perfect mixtures" can be divided into "simple bodies", then in the book "The New System of Chemical Philosophy" of 1808, John Dalton put forward the first idea about which of the substances, to which type is subject. But before that, Lavoisier proved that mass is constant, it does not disappear anywhere and does not appear out of nowhere. Davy also discovered a number of chemical elements: hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur, phosphorus, sodium and potassium were discovered by him in 1807, and in 1808 he also discovered such elements as calcium, strontium, barium and magnesium. Iron, zinc, copper, lead, silver, platinum, gold and mercury were also discovered.

Their discovery did not take much more work, since many of them were isolated from ores, isolated from chemical compounds. And already water, ammonia, carbon dioxide and many other compounds were already considered perfect mixtures. And now, Dalton, having everything he needed, decided to determine the atomic masses of all chemical elements, and also enter them all into tables, that is, classify them. So, Dalton introduced his own designation for each chemical element, for example, for hydrogen he introduced a circle icon with a dot in the center, for oxygen there was a sign – an ordinary circle, and for carbon there was a sign of a painted black circle, etc. To calculate the masses of atoms, Dalton conducted some experiments.

Initially, he evaporated water, and on the upper part he installed substances with which hydrogen reacted better, calculating changes in both the mass of the substance with which the interaction took place or from the volume of steam, Dalton could determine which part of the water consists of hydrogen and which of oxygen. Thus, having determined that 1/8 of the total mass of water consists of hydrogen, and 7/8 of oxygen, Dalton decided that oxygen is heavier than hydrogen and assigned a mass equal to 1 to hydrogen and 7 to oxygen. The same analysis of ammonia showed 1 for hydrogen and 5 for nitrogen. After analyzing it in this way, Dalton compiled his own table of chemical elements.

Needless to say, although this was the first step on the path of knowledge, all these statements were not true. But it lasted for quite a long time and various assumptions were based on it. One of these hypotheses was published in the journal "Philosophical Annals" by the London physician William Prout and was devoted to the idea that all atoms consist of hydrogen. But of course, this hypothesis was not true like many other assumptions of that time.

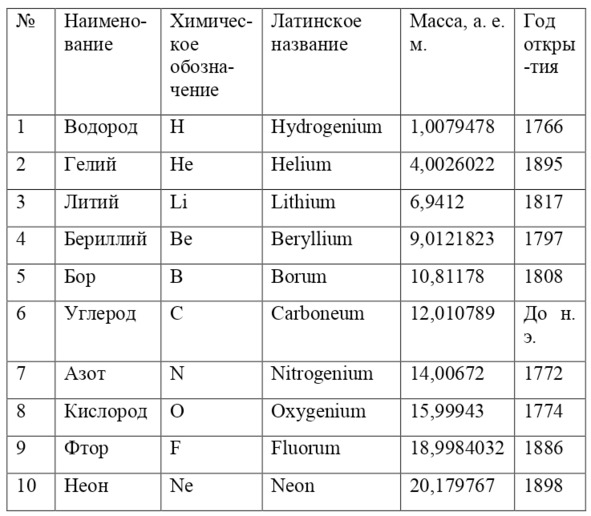

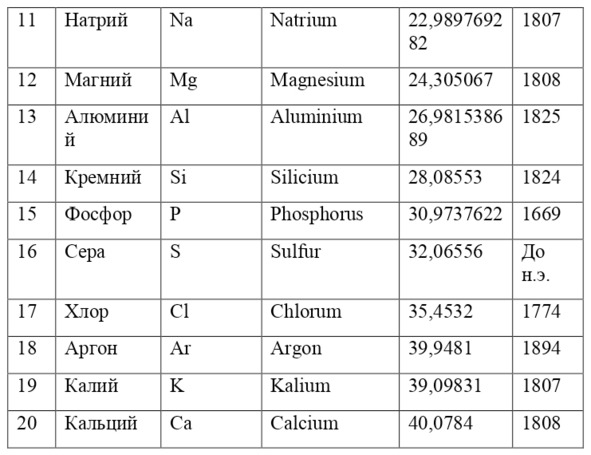

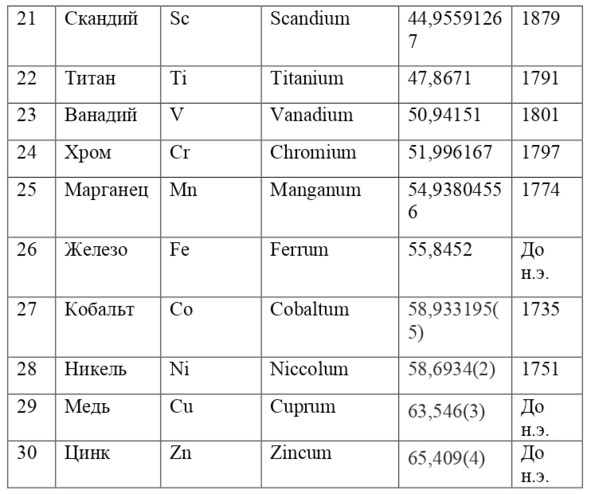

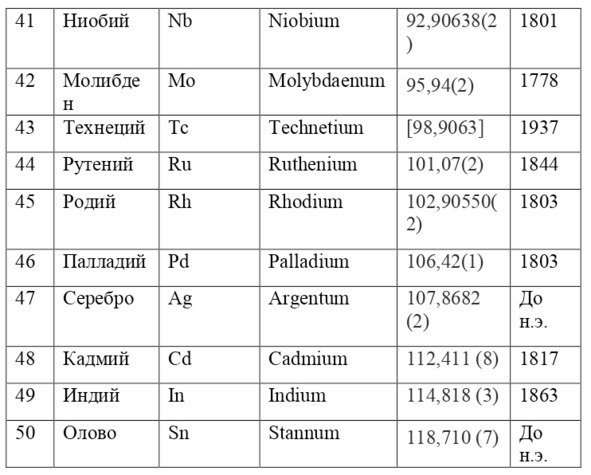

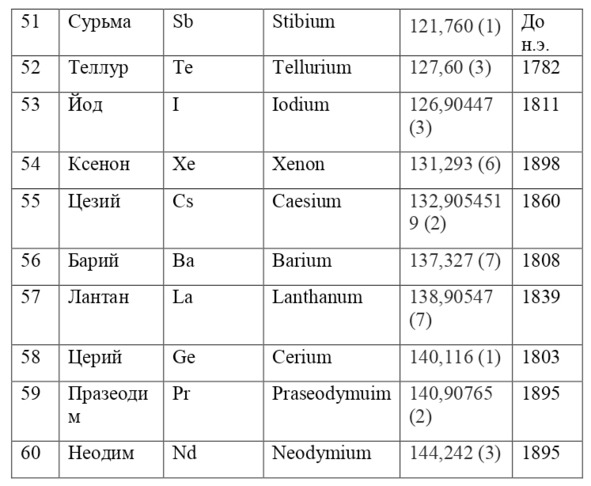

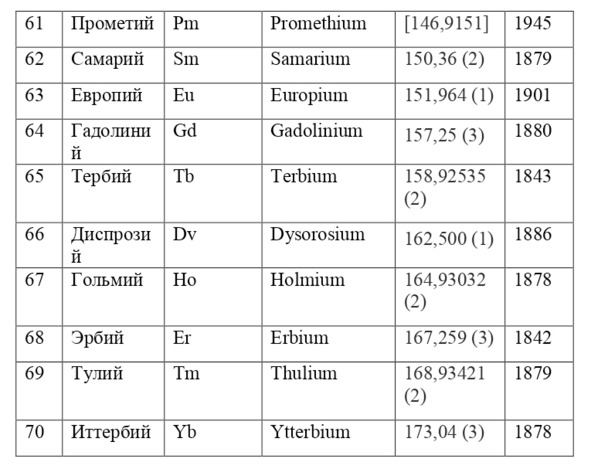

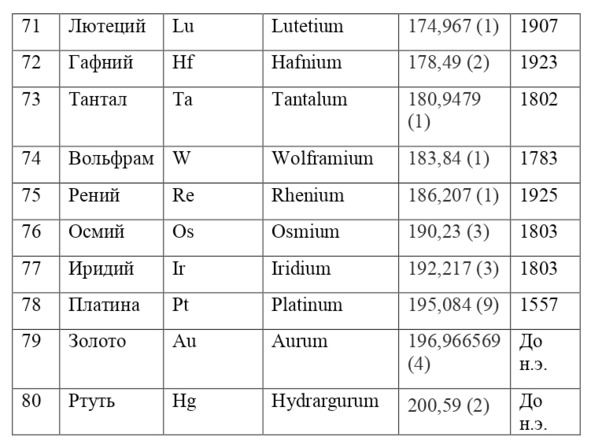

And if then, the atomic unit of mass was taken as the mass of a hydrogen atom, then today the exact unit is considered to be 1/12 of the mass of a carbon atom and is named as an A. E. M. or atomic unit of mass. And chemical elements today are usually designated from the first two or one letter of their name in Latin, for example, hydrogen is designated as H due to the name Hydrogenium («Generating water» in Latin), Nitrogen – N or Nitrogenium – «Giving birth to saltpeter», iron – Fe or Ferrum, copper – Cu – Cuprum, carbon – C – Carboneum. This system was adopted on September 3, 1860 after the Italian chemist Stanislao Cannizzaro at the International Congress in Karlsruhe proposed this method in his speech.

After that, it was customary to record chemical compounds using these symbols, and the number of atoms was indicated in the lower right corner, so for example, the compound of carbon and hydrogen (water) is written as H2O, ammonia – NH3, sulfuric acid H2SO4, etc. This method is very convenient because it creates opportunities for using symbolic notation and not there is no need to write down all the symbols several times, for example, for a cane sugar molecule – C6H12O6 (6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms and 6 oxygen atoms). Instead of CCCCCCHHHHHHHHHHHOOOOOO, you can easily and simply write C6H12O6.

If everything is already clear with the notation, then there remains one very interesting consequence. Taking into account the fact that 1 atomic unit of mass is equal to 1/12 of a carbon atom, this makes it possible to calculate the masses of all chemical elements using compounds with carbon. For a better explanation, let’s give an example. Suppose there is a certain compound of carbon and hydrogen, if you act on it with an electric current or heat it, then it is possible, if it is solid, to melt, if the liquid is evaporated and to obtain a finite volume of carbon and hydrogen. From the ratio of their masses and volumes, it is possible to determine how many hydrogen atoms account for one carbon atom, and already from the ratio of their masses, it is possible to calculate the mass of hydrogen. So if we divide the methane compound into carbon and hydrogen, we get 4 times more hydrogen than carbon in volume, so we can conclude that for 1 carbon atom, there are 4 hydrogen atoms and the CH4 compound is obtained. And as for the masses, in this ratio it turns out that the mass of 1 hydrogen atom is almost 1/12 of the mass of a carbon atom or 1.00811 am. Exactly the same method can be used to determine the masses for all other atoms (Table 1.1).

But what exactly is this value equal to 1 A. E. M.? If you answer this question, you can find the masses of all other types of atoms, at the same time prove their reality. But none of the atoms, even the largest of them, can be seen in any microscope at that time. The situation is saved by the discovery made in 1828 by the English botanist Robert Brown. When a new microscope was brought to Robert Brown, he left it in the garden, and in the morning, dew drops formed on the "table" of the microscope, and Brown himself forgot to wipe them and automatically looked into the microscope. What was his surprise when he saw that the pollen particles in the dew drop were randomly moving. The particles are not alive and cannot move by themselves. It just couldn't be. But then, when this movement was recorded, some assumptions and hypotheses appeared to explain this phenomenon.

Perhaps this movement was explained by the fact that there are flows in the drop itself due to pressure and temperature differences, such as, for example, the movement of dust particles in the air. After all, if microscopic objects have such a movement, then it must also be in particles with a large size, like dust particles. After all, the movement of dust particles is explained precisely by air flows. But this idea was not confirmed, because the particles did not move in the same direction. After all, in the flow or flow of a jet of air, water or other medium, particles should move only in one direction, and the movement of microscopic particles in Brownian motion does not depend on each other.

In that case, perhaps this movement is the result of the environment? From external sounds, table shakes and other objects? This statement has already been refuted by the French physicist Gui. After conducting a series of experiments, he compared the chaotic Brownian motion with the movement in a remote basement in the village with the movement in the middle of a noisy street. The movements, of course, affected, but they affected only the entire drop as a whole, and not the Brownian motion of the particles itself. Moreover, there was the same movement in gases as in liquids, a striking example of such a movement is the movement of coal particles in tobacco smoke. For a visual example, you can compare two pictures. The way tobacco smoke forms and spreads in the air and the picture in the water, after a drop of paint or dye is dropped into it.

The explanation for all this is given by Carbonel, it is he who explains that the particles fall under the tremors from all sides, which causes their chaotic movement. And the smaller the particles, the more active their movement becomes, since the shocks throw them away more and more, and if the bodies are large, then the number of shocks from all sides somehow becomes almost equal, so furniture, buildings and people themselves do not vibrate by themselves and Brownian motion is not observed. It also turns out that as much as the temperature is higher, so is the velocity of these particles.

This picture becomes even clearer when Richard Sigmondi managed to invent his ultramicroscope, on the basis of which even smaller particles could already be seen. And their movement was no longer a simple movement, it was flickering, jumping and splashing, as Sigmondi himself would describe. But in order to better see this picture, the Svedberg method helped, which reduced the time of the passage of light into the microscope, thanks to which it was possible to fix exactly the specified moment, that is, it was possible to photograph this movement. And with a decrease in the time interval, doing less and less, it became possible to reach the moment when the particles in the photo simply froze in place.

And finally, the year 1908 comes, when it was finally established that atoms exist, have mass and are the basic units of matter, and combining with each other form molecules – particles of any complex compound, be it water, acid, the human body, etc.

So, Jean Perrin, a French physicist, decides to study atoms and finds a very amazing way to do it. He takes a drop of gummigut, pieces of rubber resin or yellow paint, if you like. By rubbing this piece in water like a bar of soap, he got yellowish water. But when he took a drop and examined it with a microscope, it turned out that the gummigut was not completely gone, but simply divided into thousands and thousands of small particles of different sizes. Perrin decided that if they are of different sizes and all these are gummigut particles, then they have different masses, therefore, they can be separated using a centrifuge. That is, if you rotate this liquid, then the heavier particles will logically separate to the wall, and the lighter ones will remain.

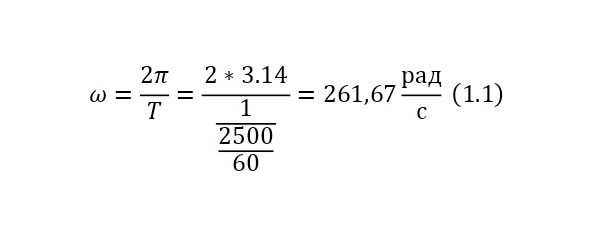

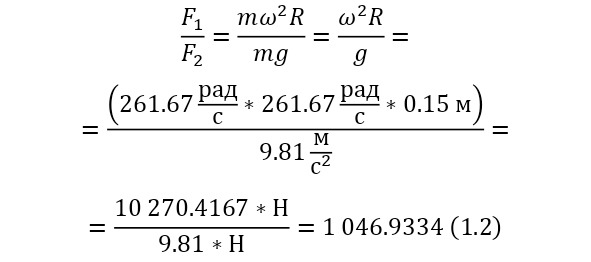

And with increasing speed, the force increases not twice, but as many times as the speed increased, due to the second degree in the centripetal acceleration formula. Consequently, Mr. Perrin could easily claim that he could separate heavy particles from light particles by strong rotation and he used a centrifuge for this, the same device that rotated with a certain frequency without spilling all the liquid. Perrin used a centrifuge, which thus rotated 2500 times per minute. And even then, only in a small part of the center, places with homogeneous particles were formed, and the rest flew to the edges. Therefore, Mr. Perrin had to use the centrifuge like this several times. Even taking into account the fact that this centrifugal force, even at a radius of 15 cm, already exceeded the force of gravity (the force of gravity of the Earth) by 1,000 times. What can be seen, given that gravity is determined by the product (multiplication) of mass by the acceleration of the fall of any object g, which is the same for all objects and is equal to 9.81 m/ s2 (meters per second squared). And based on the fact that 2500 revolutions per minute are performed, it can be calculated that the angular acceleration according to (1.1).

It remains only to calculate the ratio and get the result (1.2).

The resulting number is indeed more than 1,000, that is, the force at a distance of only 15 cm is already greater than the force of attraction of the entire planet by 1,046.9 times. Thus, in the end, Perrin managed to obtain water only with the specified particle diameters – 0.5 (5 out of 10 parts), 0.46, 0.37, 0.21 and 0.14 microns (1 thousandth of a millimeter or 10-6 m, which corresponds to a division of 1/1000000). And finally, having obtained such liquids only with a certain type of gummigut particles (such liquids are called emulsions), Perrin decided to experiment and observe them in a microscope. Watching them, turning the entire cuvette on its side, Perrin noticed that these particles decrease with increasing height. If at first they filled the entire liquid evenly or randomly, then they decreased with height, just as the air in the upper layers of the atmosphere decreases. And that was already a thought! If we compare this with the decrease in air at high altitudes, then we can establish a pattern. But in order to check it, Perrin decided to count these grains at each height.

Alas, it was not possible to photograph them, because the photos were not too clear due to the small size of less than 0.5 microns, and Perrin measured the number of gummigut particles several times at different heights, since the particles were moving, it was not possible to accurately count, so Perrin had to count several times even at the same height, and then say the average number. So at one time, he carried out the calculation at a height of 5, 35, 65 and 95 microns. And it turned out that the number of particles at a height of 35 microns was equal to almost half of the number of particles at a height of 5 microns, and at a height of 65 – half of 35, etc. And this already perfectly fell under the law of reducing atmospheric pressure (the force of oxygen pressure on our planet) with an altitude that was determined by Blaise Pascal, the famous French scientist, back in the 17th century. He measured the amount of oxygen using the Torricelli barometer, a pressure measuring device, the principle of which is that at normal air pressure from above, the mercury in the tube is at a certain height, when the pressure becomes less, the mercury can rise, and if the pressure increases, then vice versa – decreases, if there is no pressure, like gravity, it is a kind of weightlessness. Having calculated the difference in the layers of the atmosphere, Pascal even then determined that oxygen decreases with increasing altitude for every 5 km. But why is there a 2-fold decrease in gummigut particles only from 5 to 35, and in the atmosphere from 5 to 10, even if we do not take into account the scale?

And it's all about the particles, because there is oxygen in the atmosphere, and here the gummigut particles are so large that they can be seen in a microscope, their diameter is 0.21 microns. The law also changes for nitrogen, carbon dioxide, etc. due to the difference in the masses of the molecules. And if we consider the e4tu emulsion as a small atmosphere, then it is already possible to calculate the real mass of the atom! It is not so difficult to make this calculation, the height at which the oxygen density becomes 2 times less is 5 km, and for gummigut – 30 microns. And 5 km is 165,000,000 times larger than 30 microns, therefore, 1 such gummigut ball with a diameter of 0.21 microns is 165,000,000 times larger than an air molecule. And it's easier to calculate the mass of this gummigut ball.

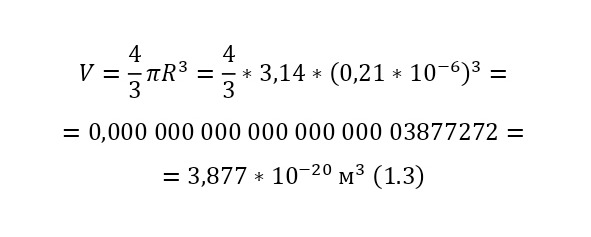

The ratio of the mass of 1 cubic meter of gummigut (in the volume of a cube with dimensions of 1 meter wide, 1 meter high and 1 meter long) to its mass is the same as that of this gummigut ball and is equal to 1,000 kg/m3 (kilograms per cubic meter) or 103 kg/m3 (10 in a cube). And the volume of the sphere for the gummigut ball is also simple. After all, in order to calculate the volume of the sphere, it is necessary to circle the circle in space, that is, multiply by its area, the area of the second circle, and then it will turn out and at the same time subtract the part of the circle where such a «revolution» went 2 times. As a result, a formula is derived similar to the formula for the area of the circle (1.3).

This volume corresponds to the mass, taking into account the force of Archimedes, that is, the force that pushes out of the water, since the gummigut particles are in the water, and not in the air, is about 10-14 grams. And if this grain is 165 million times larger than the oxygen molecule, therefore, the mass of the oxygen atom is 5.33 * 10-23 grams. And this is already, as can be learned from comparisons of the masses of hydrogen and oxygen (taking into account that there are 2 atoms in the oxygen molecule, since it is a gas) 32 times more than the mass of hydrogen, therefore, the mass of the hydrogen atom is 1,674 * 10-27 kg, that is, 1 gram of hydrogen already contains 597,371,565,113,500 597 371 565 114 hydrogen atoms! And so, it was already possible to compare the mass of the atom with A. E. M., having obtained that the mass of the hydrogen atom is 1.007825 A. E. M. It was in this way that Perrin was able to do the seemingly impossible – to weigh atoms and molecules, and now atoms and molecules were not a fairy tale, but a real science with precise calculations, formulas and instructions!

And even Oswald, an ardent opponent of the atomistic theory, wrote in the preface to his chemistry course: "Now I am convinced that recently we have received experimental proof of the discontinuous, or granular, structure of matter – proof that the atomistic hypothesis has been searching in vain for hundreds and thousands of years. The coincidence of Brownian motion with the requirements of this hypothesis gives the right to the most cautious scientist to talk about experimental proof of the atomistic theory of matter. The atomistic hypothesis has thus become a scientific, well-grounded theory."

And finally, one could safely say that everything in this universe, from planets and stars, to you and me, to everything that the eye sees, consists of atoms, but how true was this statement? And perhaps scientists had to find other particles…

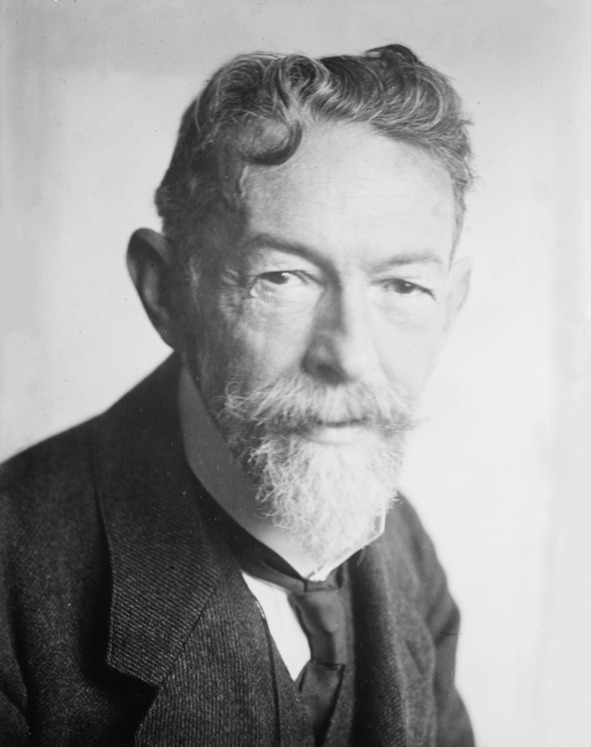

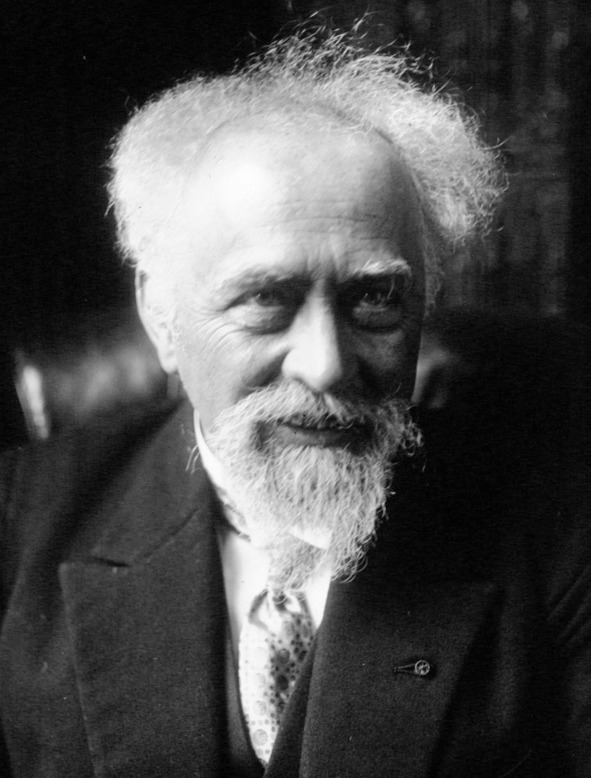

Images for Chapter 1

Figure 1.1. Democritus is one of the first authors of the idea of atomism

Figure 1.2. Leucippus is one of the first people to support and develop atomism

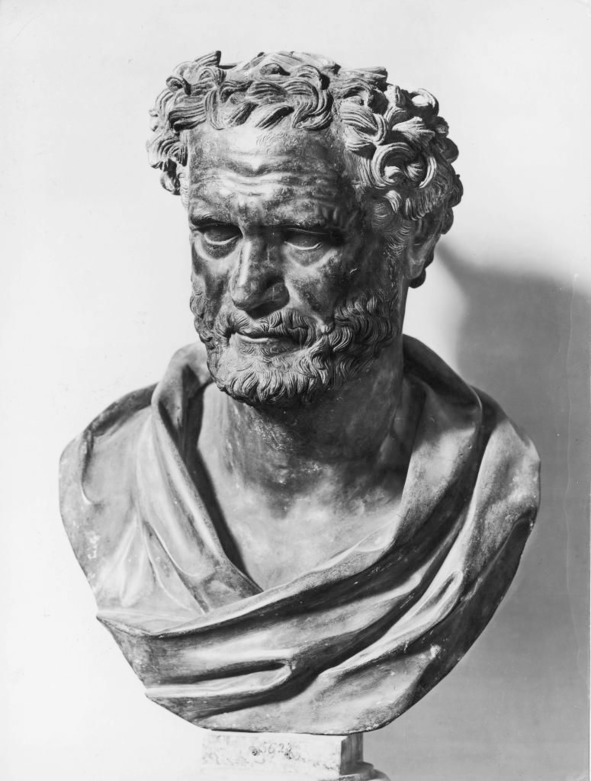

Figure 1.3. Epicurus is a philosopher who made a great contribution to the theory of atomism

Figure 1.4. Plato – assumed that atoms have the forms of Platonic bodies

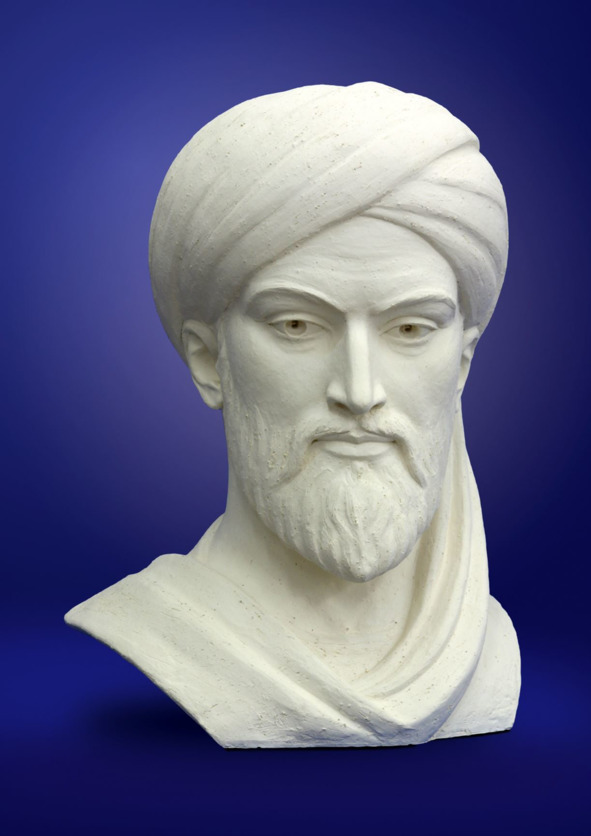

Figure 1.5. Abu Rayhan Beruni – was a supporter of atomism and believed that the atom is also divisible, but not infinitely

Figure 1.6. Abu Ali ibn Husayn ibn Abdallah ibn Sina – also known as Avicenna, proponent of the theory of atomism

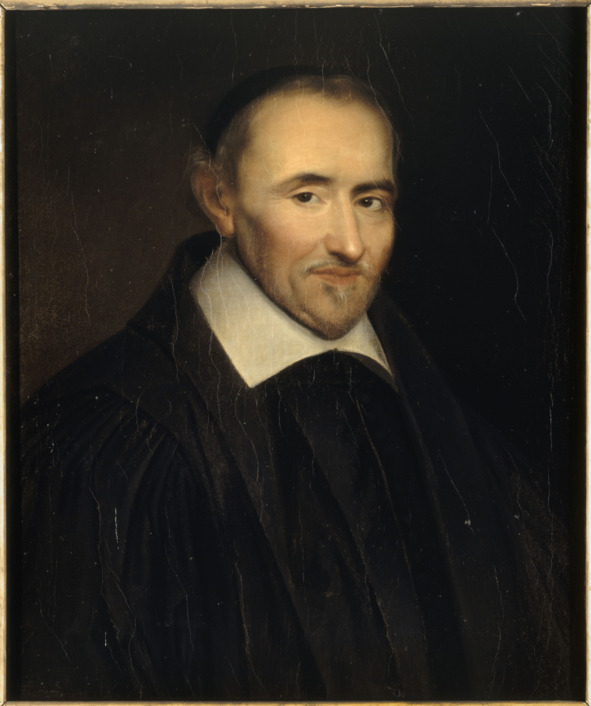

Figure 1.7. Pierre Gassendi – revived the idea of atomism

Figure 1.8. Robert Boyle is a scientist who defended atomism in his outstanding work «The Skeptical Chemist»

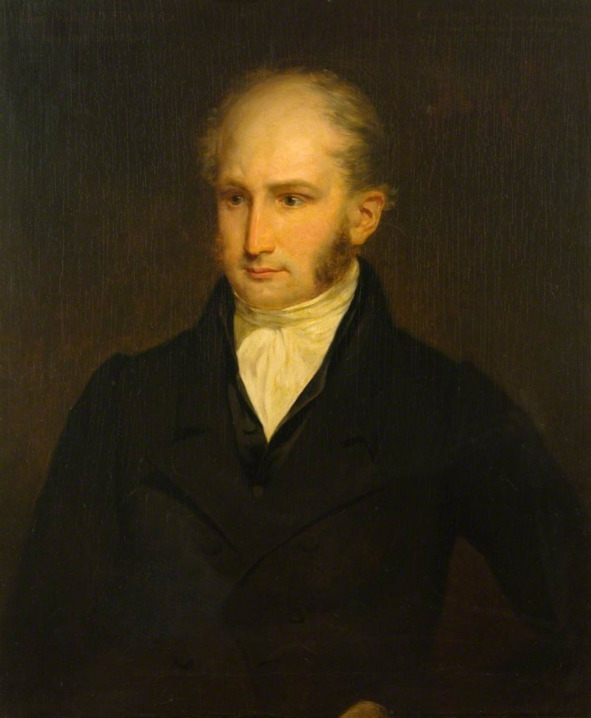

Figure 1.9. Isaac Newton is a great scientist who also became a supporter of atomism

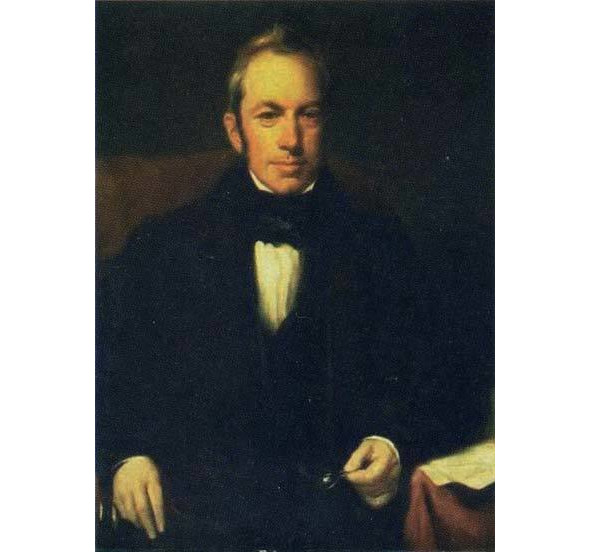

Figure 1.10. John Dalton is one of the first proponents of the revival of atomism, as well as the creator of one of the first classification tables

Figure 1.11. The Dalton Table

Figure 1.12. William Prout – believed that everything in the world consists of hydrogen

Figure 1.13. Stanislao Cannizzaro – proposed to designate chemical elements by their Latin names, introducing modern symbols

Figure 1.14. Robert Brown – discoverer of Brownian motion

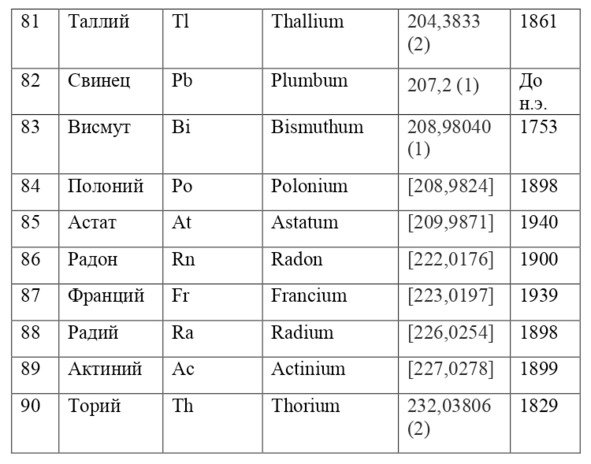

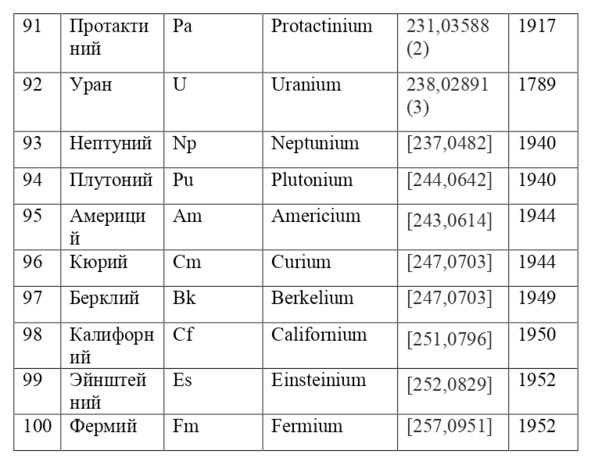

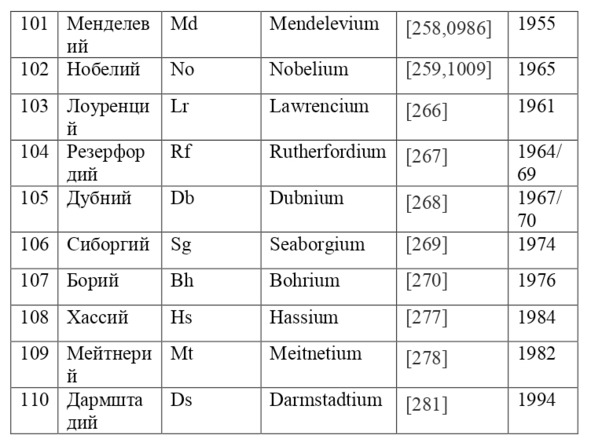

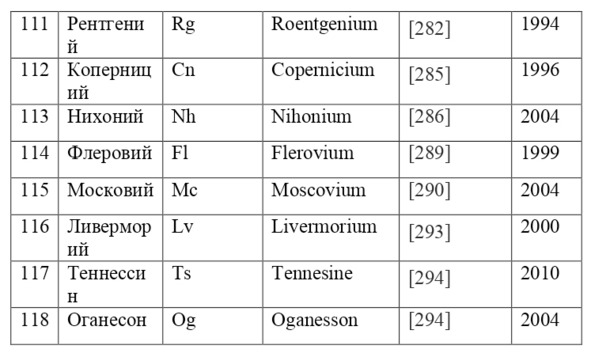

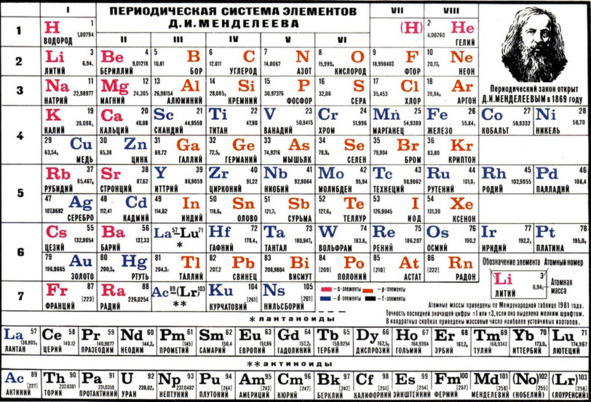

Figure 1.15. Dmitry Ivanovich’s periodic system is what Dalton once wanted to create

Figure 1.16. Richard Sigmondi – inventor of the ultramicroscope

Figure 1.17. Jean Perrin is a man who proved the existence of atoms by determining their weight

Chapter 2. Inside the atom and the features of the nucleus

The atom was considered indivisible for a long time, its very name means "indivisible", but over time, I still had to agree with the fact that the atom is divisible and has a structure, despite the fact that a lot of time has passed. The description of the further stages of the development of the physics of the atomic nucleus and elementary particles closely borders on various mathematical operations, detailed descriptions of which will no longer be given, as well as many simplifications to general theories, which would greatly increase the amount of information, and some "basics" have already been described in the previous introductory chapter. In the same chapter, the phenomena of radioactivity will be described using analysis using a complete mathematical apparatus.