полная версия

полная версияThirty Years' View (Vol. I of 2)

"On the 28th ult. this committee assembled at the banking house, and again found the room they expected to find set apart for their use, preoccupied by the committee of directors, and others, officers of the bank. And instead of such assurances as they had a right to expect, they received copies of two resolutions adopted by the board of directors, in which they were given to understand that their continued occupation of the room must be considered a favor and not a matter of right; and in which the board indulge in unjust commentaries on the resolution of the House of Representatives; and intimate an apprehension that your committee design to make their examinations secret, partial, unjust, oppressive and contrary to common right."

On receiving this offensive communication, manifestly intended to bring on a quarrel, the committee adopted a resolution to sit in a room of their hotel, and advised the bank accordingly; and required the president and directors to submit the books to their inspection in the room so chosen, at a day and hour named. To this the directors answered that they could not comply; and the committee, desirous to do all they could to accomplish the investigation committed to them, then gave notice that they would attend at the bank on a named day and hour to inspect the books in the bank itself – either at the counter, or in a room. Arriving at the appointed time, and asking to see the books, they were positively refused, reasons in writing being assigned for the refusal. They then made a written request to see certain books specifically and for a specified purpose, namely, to ascertain the truth of the report of the government directors in using the money and power of the bank in politics, in elections, or in producing the distress. The manner in which this call was treated must be given in the words of the report itself; thus:

"Without giving a specific answer to these calls for books and papers, the committee of directors presented a written communication, which was said to be 'indicative of the mode of proceeding deemed right by the bank.'

"The committee of the board in that communication, express the opinion, that the inquiry can only be rightfully extended to alleged violations of the charter, and deny virtually the right of the House of Representatives to authorize the inquiries required in the resolution.

"They also required of the committee of investigation, 'when they asked for books and papers, to state specifically in writing, the purposes for which they are proposed to be inspected; and if it be to establish a violation of the charter, then to state specifically in writing, what are the alleged or supposed violations of charter, to which the evidence is alleged to be applicable.'

"To this extraordinary requirement, made on the supposition that your committee were charged with the duty of crimination, or prosecution for criminal offence, and implying a right on the part of the directors to determine for what purposes the inspection should be made, and what books or papers should be submitted to inspection, your committee replied, that they were not charged with the duty of criminating the bank, its directors, or others; but simply to inquire, amongst other things, whether any prosecution in legal form should be instituted, and from the nature of their duties, and the instructions of the House of Representatives, they were not bound to state specifically in writing any charges against the bank, or any special purpose for which they required the production of the books and papers for inspection."

The committee then asked for copies of the accounts and entries which they wished to see, and were answered that it would require the labor of two clerks for ten months to make them out; and so declined to give the copies. The committee finding that they could make nothing out of books and papers, determined to change their examination of things into that of persons; and for that purpose had recourse to the subpœnas, furnished by the House; and had them served by the United States marshal on the president and directors. This subpœna, which contained a clause of duces tecum, with respect to the books, was so far obeyed as to bring the directors in person before the committee; and so far disobeyed as to bring them without the books, and so far exceeded as to bring them with a written refusal to be sworn – for reasons which they stated. But this part deserves to be told in the language of the report; which says:

"Believing they had now exhausted, in their efforts to execute the duty devolved upon them, all reasonable means depending solely upon the provisions of the bank charter, to obtain the inspection of the books of this corporation, your committee were at last reluctantly compelled to resort to the subpœnas which had been furnished to them under the seal of this House, and attested by its clerk. They, thereby, on the 9th inst. directed the marshal of the eastern district of Pennsylvania to summon Nicholas Biddle, president, and thirteen other persons, directors of the bank, to attend at their committee room, on the next day, at twelve o'clock, at noon, to testify concerning the matters of which your committee were authorized to inquire, and to bring with them certain books therein named for inspection. The marshal served the summons in due form of law, and at the time appointed, the persons therein named appeared before the committee and presented a written communication signed by each of them, as the answer of each to the requirements of the subpœna, which is in the appendix to this report. In this paper they declare 'that they do not produce the books required, because they are not in the custody of either of us, but as has been heretofore stated, of the board,' and add, 'considering that as corporators and directors, we are parties to the proceeding – we do not consider ourselves bound to testify, and therefore respectfully decline to do so.'"

This put an end to the attempted investigation. The committee returned to Washington – made report of their proceedings, and moved: "That the speaker of this House do issue his warrant to the sergeant-at-arms, to arrest Nicholas Biddle, president – Manuel Eyre, Lawrence Lewis, Ambrose White, Daniel W. Cox, John Holmes, Charles Chauncey, John Goddard, John R. Neff, William Platt, Matthew Newkirk, James C. Fisher, John S. Henry, and John Sergeant, directors – of the Bank of the United States, and bring them to the bar of this House to answer for the contempt of its lawful authority." This resolve was not acted upon by the House; and the directors had the satisfaction to enjoy a negative triumph in their contempt of the House, flagrant as that contempt was upon its own showing, and still more so upon its contrast with the conduct of the same bank (though under a different set of directors), in the year 1819. A committee of investigation was then appointed, armed with the same powers which were granted to this committee of the year 1834, and the directors of that time readily submitted to every species of examination which the committee chose to make. They visited the principal bank at Philadelphia, and several of its branches. They had free and unrestrained access to the books and papers of the bank. They were furnished by the officers with all the copies and extracts they asked for. They summoned before them the directors and officers of the bank, examined them on oath, took their testimony in writing – and obtained full answers to all their questions, whether they implied illegalities violative of the charter, or abuses, or mismanagement, or mistakes and errors.

CHAPTER CVII.

MR. TANEY'S REPORT ON THE FINANCES – EXPOSURE OF THE DISTRESS ALARMS – END OF THE PANIC

About the time when the panic was at its height, and Congress most heavily assailed with distress memorials, the Secretary of the Treasury was called upon by a resolve of the Senate for a report upon the finances – with the full belief that the finances were going to ruin, and that the government would soon be left without adequate revenue, and driven to the mortifying resource of loans. The call on the Secretary was made early in May, and was answered the middle of June; and was an utter disappointment to those who called for it. Far from showing the financial decline which had been expected, it showed an increase in every branch of the revenue! and from that authentic test of the national condition, it was authentically shown that the Union was prosperous! and that the distress, of which so much was heard, was confined to the victims of the United States Bank, so far as it was real; and that all beyond that was fictitious and artificial – the result of the machinery for organizing panic, oppressing debtors, breaking up labor, and alarming the timid. When the report came into the Senate, the reading of it was commenced at the table of the Secretary, and had not proceeded far when Mr. Webster moved to cease the reading, and send it to the Committee on Finance – that committee in which a report of that kind could not expect to find either an early or favorable notice. We had expected a motion to get rid of it, in some quiet way, and had prepared for whatever might happen. Mr. Taney had sent for me the day before it came in; read it over with me; showed me all the tables on which it was founded; and prepared me to sustain and emblazon it: for it was our intention that such a report should go to the country, not in the quiet, subdued tone of a State paper, but with all the emphasis, and all the challenges to public attention, which the amplifications, the animation, and the fire and freedom which the speaking style admitted. The instant, then, that Mr. Webster made his motion to stop the reading, and refer the report to the Finance Committee, Mr. Benton rose, and demanded that the reading be continued: a demand which he had a right to make, as the rules gave it to every member. He had no occasion to hear it read, and probably heard nothing of it; but the form was necessary, as the report was to be the text of his speech. The instant it was done, he rose and delivered his speech, seizing the circumstance of the interrupted reading to furnish the brief exordium, and to give a fresh and impromptu air to what he was going to say. The following is the speech:

Mr. Benton rose, and said that this report was of a nature to deserve some attention, before it left the chamber of the Senate, and went to a committee, from which it might not return in time for consideration at this session. It had been called for under circumstances which attracted attention, and disclosed information which deserved to be known. It was called for early in May, in the crisis of the alarm operations, and with confident assertions that the answer to the call would prove the distress and the suffering of the country. It was confidently asserted that the Secretary of the Treasury had over-estimated the revenues of the year; that there would be a great falling off – a decline – a bankruptcy; that confidence was destroyed – enterprise checked – industry paralyzed – commerce suspended! that the direful act of one man, in one dire order, had changed the face of the country, from a scene of unparalleled prosperity to a scene of unparalleled desolation! that the canal was a solitude, the lake a desert waste of waters, the ocean without ships, the commercial towns deserted, silent, and sad; orders for goods countermanded; foreign purchases stopped! and that the answer of the Secretary would prove all this, in showing the falsity of his own estimates, and the great decline in the revenue and importations of the country. Such were the assertions and predictions under which the call was made, and to which the public attention was attracted by every device of theatrical declamation from this floor. Well, the answer comes. The Secretary sends in his report, with every statement called for. It is a report to make the patriot's heart rejoice! full of high and gratifying facts; replete with rich information; and pregnant with evidences of national prosperity. How is it received – how received by those who called for it? With downcast looks, and wordless tongues! A motion is even made to stop the reading! to stop the reading of such a report! called for under such circumstances; while whole days are given up to reading the monotonous, tautologous, and endless repetitions of distress memorials, the echo of our own speeches, and the thousandth edition of the same work, without emendation or correction! All these can be read, and printed, too, and lauded with studied eulogium, and their contents sent out to the people, freighted upon every wind; but this official report of the Secretary of the Treasury, upon the state of their own revenues, and of their own commerce, called for by an order of the Senate, is to be treated like an unwelcome and worthless intruder; received without a word – not even read – slipped out upon a motion – disposed of as the Abbé Sieyes voted for the death of Louis the Sixteenth: mort sans phrase! death, without talk! But he, Mr. B., did not mean to suffer this report to be dispatched in this unceremonious and compendious style. It had been called for to be given to the people, and the people should hear of it. It was not what was expected, but it is what is true, and what will rejoice the heart of every patriot in America. A pit was dug for Mr. Taney; the diggers of the pit have fallen into it; the fault is not his; and the sooner they clamber out, the better for themselves. The people have a right to know the contents of this report, and know them they shall; and if there is any man in this America, whose heart is so constructed as to grieve over the prosperity of his country, let him prepare himself for sorrow; for the proof is forthcoming, that never, since America had a place among nations, was the prosperity of the country equal to what it is at this day!

Mr. B. then requested the Secretary of the Senate to send him the report, and comparative statements; which being done, Mr. B. opened the report, and went over the heads of it to show that the Secretary of the Treasury had not over-estimated the revenue of the year, as he had been charged, and as the report was expected to prove: that the revenue was, in fact, superior to the estimate; and that the importations would equal, if not exceed, the highest amount that they had ever attained.

To appreciate the statements which he should make, Mr. B. said it was necessary for the Senate to recollect that the list of dutiable articles was now greatly reduced. Many articles were now free of duty, which formerly paid heavy duties; many others were reduced in duty; and the fair effect of these abolitions and reductions would be a diminution of revenue even without a diminution of imports; yet the Secretary's estimate, made at the commencement of the session, was more than realized, and showed the gratifying spectacle of a full and overflowing treasury, instead of the empty one which had been predicted; and left to Congress the grateful occupation of further reducing taxes, instead of the odious task of borrowing money, as had been so loudly anticipated for six months past. The revenue accruing from imports in the first quarter of the present year, was 5,344,540 dollars; the payments actually made into the treasury from the custom-houses for the same quarter, were 4,435,386 dollars; and the payments from lands for the same time, were 1,398,206 dollars. The two first months of the second quarter were producing in a full ratio to the first quarter; and the actual amount of available funds in the treasury on the 9th day of this month, was eleven millions, two hundred and forty-nine thousand, four hundred and twelve dollars. The two last quarters of the year were always the most productive. It was the time of the largest importations of foreign goods which pay most duty – the woollens – and the season, also, for the largest sale of public lands. It is well believed that the estimate will be more largely exceeded in those two quarters than in the two first; and that the excess for the whole year, over the estimate, will be full two millions of dollars. This, Mr. B. said, was one of the evidences of public prosperity which the report contained, and which utterly contradicted the idea of distress and commercial embarrassment which had been propagated, from this chamber, for the last six months.

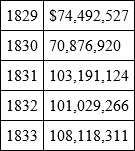

Mr. B. proceeded to the next evidence of commercial prosperity; it was the increased importations of foreign goods. These imports, judging from the five first months, would be seven millions more than they were two years ago, when the Bank of the United States had seventy millions loaned out; and they were twenty millions more than in the time of Mr. Adams's administration. At the rate they had commenced, they would amount to one hundred and ten millions for the year. This will exceed whatever was known in our country. The imports, for the time that President Jackson has served, have regularly advanced from about $74,000,000 to $108,000,000. The following is the statement of these imports, from which Mr. B. read:

Mr. B. said that the imports of the last year were greater in proportion than in any previous year; a temporary decline might reasonably have been expected; such declines always take place after excessive importations. If it had occurred now, though naturally to have been expected, the fact would have been trumpeted forth as the infallible sign – the proof positive – of commercial distress, occasioned by the fatal removal of the deposits. But, as there was no decline, but on the contrary, an actual increase, he must claim the evidence for the other side of the account, and set it down as proof positive that commerce is not destroyed; and, consequently, that the removal of the deposits did not destroy commerce.

The next evidence of commercial prosperity which Mr. B. would exhibit to the Senate, was in the increased, and increasing number of ship arrivals from foreign ports. The number of arrivals for the month of May, in New-York, was two hundred and twenty-three, exceeding by thirty-six those of the month of April, and showing not only a great, but an increasing activity in the commerce of that great emporium – he would not say of the United States, or even of North America – but he would call it that great emporium of the two Americas, and of the New World; for the goods imported to that place, were thence distributed to every part of the two Americas, from the Canadian lakes to Cape Horn.

A third evidence of national prosperity was in the sales of the public lands. Mr. B. had, on a former occasion, adverted to these sales, so far as the first quarter was concerned; and had shown, that instead of falling off, as had been predicted on this floor, the revenue from the sales of these lands had actually doubled, and more than doubled, what they were in the first quarter of 1833. The receipts for lands for that quarter, were $668,526; for the first quarter of the present year they were $1,398,206; being two to one, and $60,000 over! The receipts for the two first months of the second quarter, were also known, and would carry the revenue from lands, for the first five months of this year, to two millions of dollars; indicating five millions for the whole year; an enormous amount, from which the people of the new States ought to be, in some degree, relieved, by a reduction in the price of lands. Mr. B. begged in the most emphatic terms, to remind the Senate, that at the commencement of the session, the sales of the public lands were selected as one of the criterions by which the ruin and desolation of the country were to be judged. It was then predicted, and the prediction put forth with all the boldness of infallible prophecy, that the removal of the deposits would stop the sales of the public lands; that money would disappear, and the people have nothing to buy with; that the produce of the earth would rot upon the hands of the farmer. These were the predictions; and if the sales had really declined, what a proof would immediately be found in the fact to prove the truth of the prophecy, and the dire effects of changing the public moneys from one set of banking-houses to another! But there is no decline; but a doubling of the former product; and a fair conclusion thence deduced that the new States, in the interior, are as prosperous as the old ones, on the sea-coast.

Having proved the general prosperity of the country from these infallible data – flourishing revenue – flourishing commerce – increased arrivals of ships – and increased sales of public lands, Mr. B. said that he was far from denying that actual distress had existed. He had admitted the fact of that distress heretofore, not to the extent to which it was charged, but to a sufficient extent to excite sympathy for the sufferers; and he had distinctly charged the whole distress that did exist to the Bank of the United States, and the Senate of the United States – to the screw-and-pressure operations of the bank, and the alarm speeches in the Senate. He had made this charge; and made it under a full sense of the moral responsibility which he owed to the people, in affirming any thing so disadvantageous to others, from this elevated theatre. He had, therefore, given his proofs to accompany the charge; and he had now to say to the Senate, and through the Senate to the people, that he found new proofs for that charge in the detailed statements of the accruing revenue, which had been called for by the Senate, and furnished by the Secretary of the Treasury.

Mr. B. said he must be pardoned for repeating his request to the Senate, to recollect how often they had been told that trade was paralyzed; that orders for foreign goods were countermanded; that the importing cities were the pictures of desolation; their ships idle; their wharves deserted; their mariners wandering up and down. Now, said Mr. B., in looking over the detailed statement of the accruing revenue, it was found that there was no decline of commerce, except at places where the policy and power of the United States Bank was predominant! Where that power or policy was predominant, revenue declined; where it was not predominant, or the policy of the bank not exerted, the revenue increased; and increased fast enough to make up the deficiency at the other places. Mr. B. proceeded to verify this statement by a reference to specified places. Thus, at Philadelphia, where the bank holds its seat of empire, the revenue fell off about one third; it was $797,316 for the first quarter of 1833, and only $542,498 for the first quarter of 1834. At New-York, where the bank has not been able to get the upper hand, there was an increase of more than $120,000; the revenue there, for the first quarter of 1833, was $3,122,166; for the first of 1834, it was $3,249,786. At Boston, where the bank is again predominant, the revenue fell off about one third; at Salem, Mass., it fell off four fifths. At Baltimore, where the bank has been defeated, there was an increase in the revenue of more than $70,000. At Richmond, the revenue was doubled, from $12,034 to $25,810. At Charleston, it was increased from $69,503 to $102,810. At Petersburg, it was slightly increased; and throughout all the region south of the Potomac, there was either an increase, or the slight falling off which might result from diminished duties without diminished importations. Mr. B. said he knew that bank power was predominant in some of the cities of the South; but he knew, also, that the bank policy of distress and oppression had not been practised there. That was not the region to be governed by the scourge. The high mettle of that region required a different policy: gentleness, conciliation, coaxing! If the South was to be gained over by the bank, it was to be done by favor, not by fear. The scourge, though so much the most congenial to the haughty spirit of the moneyed power, was only to be applied where it would be submitted to; and, therefore, the whole region south of the Potomac, was exempted from the lash.

Mr. B. here paused to fix the attention of the Senate upon these facts. Where the power of the bank enabled her to depress commerce and sink the revenue, and her policy permitted her to do it, commerce was depressed; and the revenue was sunk, and the prophecies of the distress orators were fulfilled; but where her power did not predominate, or where her policy required a different course, commerce increased, and the revenue increased; and the result of the whole is, that New-York and some other anti-bank cities have gained what Philadelphia and other bank cities have lost; and the federal treasury is just as well off, as if it had got its accustomed supply from every place.