полная версия

полная версияThirty Years' View (Vol. I of 2)

2. This great and delicate power, thus involving the sacred relations of debtor and creditor, and the actual rise or fall in the value of every man's property, Mr. B. undertook to affirm, could not be delegated. It was a trust from the State governments to the federal government. The State governments divested themselves of this power, and invested the federal government with it, and made its exercise depend upon the three branches of the new government; and this new government could no more delegate it, than they could delegate any other great power which they were bound to execute themselves. Not a word of this regulating power, Mr. E. said, was heard of when the first bank was chartered, in the year 1791. No person whispered such a reason for the establishment of a bank at that time; the whole conception is newfangled – an afterthought – growing out of the very evils which the bank itself has brought upon the country, and which are to be cured by putting down that great bank; after which, the Congress and the judiciary will easily manage the small banks, by holding them up to specie payments, and excluding every unsolid note from revenue payments.

3. Mr. B. said that the government ought not to delegate this power, if it could. It was too great a power to be trusted to any banking company whatever, or to any authority but the highest and most responsible which was known to our form of government. The government itself ceased to be independent – it ceases to be safe – when the national currency is at the will of a company. The government can undertake no great enterprise, neither of war nor peace, without the consent and co-operation of that company; it cannot count its revenues for six months ahead without referring to the action of that company – its friendship or its enmity – its concurrence or opposition – to see how far that company will permit money to be plenty, or make it scarce; how far it will let the moneyed system go on regularly, or throw it into disorder; how far it will suit the interests, or policy, of that company to create a tempest, or to suffer a calm, in the moneyed ocean. The people are not safe when a company has such a power. The temptation is too great – the opportunity too easy – to put up and put down prices; to make and break fortunes; to bring the whole community upon its knees to the Neptunes who preside over the flux and reflux of paper. All property is at their mercy. The price of real estate – of every growing crop – of every staple article in market – is at their command. Stocks are their playthings – their gambling theatre – on which they gamble daily, with as little secrecy, and as little morality, and far more mischief to fortunes, than common gamblers carry on their operations. The philosophic Voltaire, a century ago, from his retreat in Ferney, gave a lively description of this operation, by which he was made a winner, without the trouble of playing. I have a friend, said he, who is a director in the Bank of France, who writes to me when they are going to make money plenty, and make stocks rise, and then I give orders to my broker to sell; and he writes to me when they are going to make money scarce, and make stocks fall, and then I write to my broker to buy; and thus, at a hundred leagues from Paris, and without moving from my chair, I make money. This, said Mr. B., is the operation on stocks to the present day; and it cannot be safe to the holders of stock that there should be a moneyed power great enough in this country to raise and depress the prices of their property at pleasure. The great cities of the Union are not safe, while a company, in any other city, have power over their moneyed system, and are able, by making money scarce or plenty – by exciting panics and alarms – to put up, or put down, the price of the staple articles in which they deal. Every commercial city, for its own safety, should have an independent moneyed system – should be free from the control and regulation of a distant, possibly a rival city, in the means of carrying on its own trade. Thus, the safety of the government, the safety of the people, the interest of all owners of property – of all growing crops – the holders of all stocks – the exporters of all staple articles – require that the regulation of the currency should be kept out of the hands of a great banking company; that it should remain where the constitution placed it – in the hands of the federal government – in the hands of their representatives who are elected by them, responsible to them, may be exchanged by them, who can pass no law for regulating currency which will not bear upon themselves as well as upon their constituents. This is what the safety of the community requires; and, for one, he (Mr. B.) would not, if he could, delegate the power of regulating the currency of this great country to any banking company whatsoever. It was a power too tremendous to be trusted to a company. The States thought it too great a power to be trusted to the State governments; he (Mr. B.) thought so too. The States confided it to the federal government; he, for one, would confine it to the federal government, and would make that government exercise it. Above all, he would not confer it upon a bank which was itself above regulation; and on this point he called upon the Senate to recollect the question, apparently trite, but replete with profound sagacity – that sagacity which it belongs to great men to possess, and to express – which was put to the Congress of 1816, when this bank charter was under discussion, and the regulation of the currency was one of the attributes with which it was to be invested; he alluded to his late esteemed friend (Mr. Randolph), and to his call upon the House to tell him who was to bell the cat? That single question contains in its answer, and in its allusion, the exact history of the people of the United States, and of the Bank of the United States, at this day. It was a flash of lightning into the dark vista of futurity, showing in 1816 what we all see in 1834.

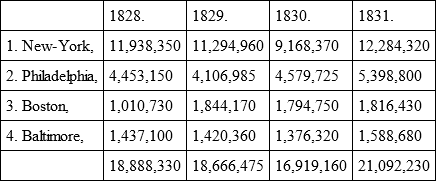

Mr. B. took up the second point on which he disagreed with the Senator from South Carolina [Mr. Calhoun], namely, the capacity of the Bank of the United States to supply a general currency to the Union. In handling this question he would drop all other inquiries – lay aside every other objection – overlook every consideration of the constitutionality and expediency of the bank, and confine himself to the strict question of its ability to diffuse and retain in circulation a paper currency over this extended Union. He would come to the question as a banker would come to it at his table, or a merchant in his counting-room, looking to the mere operation of a money system. It was a question for wise men to think of, and for abler men than himself to discuss. It involved the theory and the science of banking – Mr. B. would say the philosophy of banking, if such a term could be applied to a moneyed system. It was a question to be studied as the philosopher studies the laws which govern the material world – as he would study the laws of gravitation and attraction which govern the movements of the planets, or draw the waters of the mountains to the level of the ocean. The moneyed system, said Mr. B., has its laws of attraction and gravitation – of repulsion and adhesion; and no man may be permitted to indulge the hope of establishing a moneyed system contrary to its own laws. The genius of man has not yet devised a bank – the historic page is yet to be written which tells of a bank – which has diffused over an extensive country, and retained in circulation, a general paper currency. England is too small a theatre for a complete example; but even there the impossibility is confessed, and has been confessed for a century. The Bank of England, in her greatest day of pre-eminence, could not furnish a general currency for England alone – a territory not larger than Virginia. The country banks furnished the local paper currency, and still furnish it as far as it is used. They carried on their banking upon Bank of England notes, until the gold currency was restored; and local paper formed the mass of local circulation. The notes of the Bank of England flowed to the great commercial capitals, and made but brief sojourn in the counties. But England is not a fair example for the United States; it is too small; a fairer example is to be found nearer home, in our own country, and in this very Bank of the United States which is now existing, and in favor of which the function of supplying a general currency to this extended confederacy is claimed. We have the experiment of this bank, not once, but twice made; and each experiment proves the truth of the laws which govern the system. The theory of bank circulation, over an extended territory, is this, that you may put out as many notes as you may in any one place, they will immediately fall into the track of commerce – into the current of trade – into the course of exchange – and follow that current wherever it leads. In these United States the current sets from every part of the interior, and especially from the South and West into the Northeast – into the four commercial cities north of the Potomac; Baltimore, Philadelphia, New-York, and Boston: and all the bank notes which will pass for money in those places, fall into the current which sets in that direction. When there, there is nothing in the course of trade to bring them back. There is no reflux in that current! It is a trade-wind which blows twelve months in the year in the same direction. This is the theory of bank circulation over extended territory; and the history of the present bank is an exemplification of the truth of that theory. Listen to Mr. Cheves. Read his report made to the stockholders at their triennial meeting in 1822. He stated this law of circulation, and explained the inevitable tendency of the branch bank notes to flow to the Northeast; the impossibility of preventing it; and the resolution which he had taken and executed, to close all the Southern and Western branches, and prevent them from issuing any more notes. Even while issuing their own notes, they had so far forgot their charter as to carry on operations, in part, upon the notes of the local banks – having collected those notes in great quantity, and loaned them out. This was reported by the investigating committee of 1819, and made one of the charges of misconduct against the bank at that time. To counteract this tendency, the bank applied to Congress for leave to issue their bank notes on terms which would have made them a mere local currency. Congress refused it; but the bank is now attempting to do it herself, by refusing to take the notes received in payment of the federal revenue, and sending it back to be paid where issued. Such was the history of the branch bank notes, and which caused that currency to disappear from all the interior, and from the whole South and West, so soon after the bank got into operation. The attempt to keep out branch notes, or to send the notes of the mother bank to any distance, being found impracticable, there was no branch currency of any kind in circulation for a period of eight or nine years, until the year 1827, when the branch checks were invented, to perform the miracle which notes could not. Mr. B. would say nothing about the legality of that invention; he would now treat them as a legal issue under the charter; and in that most favorable point of view for them, he would show that these branch checks were nothing but a quack remedy – an empirical contrivance – which made things worse. By their nature they were as strongly attracted to the Northeast as the branch notes had been; by their terms they were still more strongly attracted, for they bore Philadelphia on their face! they were payable at the mother bank! and, of course, would naturally flow to that place for use or payment. This was their destiny, and most punctually did they fulfil it. Never did the trade-winds blow more truly – never did the gulf stream flow more regularly – than those checks flowed to the Northeast! The average of four years next ensuing the invention of these checks, which went to the mother bank, or to the Atlantic branches north of the Potomac, including the branch notes which flowed with them, was about nineteen millions of dollars per annum! Mr. B. then exhibited a table to prove what he alleged, and from which it appeared that the flow of the branch paper to the Northeast was as regular and uniform as an operation of nature; that each city according to its commercial importance, received a greater or less proportion of this inland paper gulf stream; and that the annual variation was so slight as only to prove the regularity of the laws by which it was governed. The following is the table which he exhibited. It was one of the tabular statements obtained by the investigating committee in 1832:

Amount of Branch Bank Paper received at—

After exhibiting this table, and taking it for complete proof of the truth of the theory which he had laid down, and that it demonstrated the impossibility of keeping up a circulation of the United States Bank paper in the remote and interior parts of the Union, Mr. B. went on to say that the story was yet but half told – the mischief of this systematic flow of national currency to the Northeast, was but half disclosed; another curtain was yet to be lifted – another vista was yet to be opened – and the effect of the system upon the metallic currency of the States was to be shown to the people and the States. This view would show, that as fast as the checks or notes of any branch were taken up at the mother bank, or at the branches north of the Potomac, an account was opened against the branch from which they came. The branch was charged with the amount of the notes or checks taken up; and periodically served with a copy of the account, and commanded to send on specie or bills of exchange to redeem them. When redeemed, they were remitted to the branch from which they came; while on the road they were called notes in transitu; and when arrived they were put into circulation again at that place – fell into the current immediately, which carried them back to the Northeast – there taken up again, charged to the branch – the branch required to redeem them again with specie or bills of exchange; and then returned to her, to be again put into circulation, and to undergo again and again, and until the branch could no longer redeem them, the endless process of flowing to the Northeast. The result of the whole was, is, and for ever will be, that the branch will have to redeem its circulation till redemption is impossible; until it has exhausted the country of its specie; and then the country in which the branch is situated is worse off than before she had a branch; for she had neither notes nor specie left. Mr. B. said that this was too important a view of the case to be rested on argument and assertion alone; it required evidence to vanquish incredulity, and to prove it up; and that evidence was at hand. He then referred to two tables to show the amount of hard money which the mother bank, under the operation of this system, had drawn from the States in which her branches were situated. All the tables were up to the year 1831, the period to which the last investigating committee had brought up their inquiries. One of these statements showed the amount abstracted from the whole Union; it was $40,040,622 20; another showed the amount taken from the Southern and Western States; it was $22,523,387 94; another showed the amount taken from the branch at New Orleans; it was $12,815,798 10. Such, said Mr. B., has been the result of the experiment to diffuse a national paper currency over this extended Union. Twice in eighteen years it has totally failed, leaving the country exhausted of its specie, and destitute of paper. This was proof enough, but there was still another mode of proving the same thing; it was the fact of the present amount of United States Bank notes in circulation. Mr. B. had heard with pain the assertion made in so many memorials presented to the Senate, that there was a great scarcity of currency; that the Bank of the United States had been obliged to contract her circulation in consequence of the removal of the deposits, and that her notes had become so scarce that none could be found; and strongly contrasting the present dearth which now prevails with the abundant plenty of these notes which reigned over a happy land before that fatal measure came to blast a state of unparalleled prosperity. The fact was, Mr. B. said, that the actual circulation of the bank is greater now than it was before the removal of the deposits; greater than it has been in any month but one for upwards of a year past. The discounts were diminished, he said, but the circulation was increased.

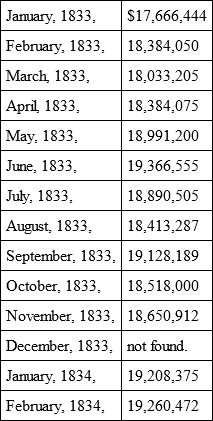

Mr. B. then exhibited a table of the actual circulation of the Bank of the United States for the whole year 1833, and for the two past months of the present year; and stated it to be taken from the monthly statements of the bank, as printed and laid upon the tables of members. It was the net circulation – the quantity of notes and checks actually out – excluding all that were on the road returning to the branch banks, called notes in transitu, and which would not be counted till again issued by the branch to which they were returned.

The following is the table:

By comparing the circulation of each month, as exhibited on this table, Mr. B. said, it would be seen that the quantity of United States Bank notes now in circulation is three quarters of a million greater than it was in October last, and a million and a half greater than it was in January, 1833. How, then, are we to account for this cry of no money, in which so many respectable men join? It is in the single fact of their flow to the Northeast. The pigeons, which lately obscured the air with their numbers, have all taken their flight to the North! But pigeons will return of themselves, whereas these bank notes will never return till they are purchased with gold and silver, and brought back. Mr. B. then alluded to a petition from a meeting in his native State, North Carolina, and in which one of his esteemed friends (Mr. Carson) late a member of the House of Representatives, was a principal actor, and which stated the absolute disappearance of United States Bank notes from all that region of country. Certainly the petition was true in that statement; but it is equally true that it was mistaken in supposing that the circulation of the bank was diminished. The table which he had read had shown the contrary; it showed an increase, instead of a diminution, of the circulation. The only difference was that it had all left that part of the country, and that it would do for ever! If a hundred millions of United States Bank notes were carried to the upper parts of North Carolina, and put into circulation, it would be but a short time before the whole would have fallen into the current which sweeps the paper of that bank to the Northeast. Mr. B. said there were four other classes of proof which he could bring in, but it would be a consumption of time, and a work of supererogation. He would not detail them, but state their heads: 1. One was the innumerable orders which the mother bank had forwarded to her branches to send on specie and bills of exchange to redeem their circulation – to pour in reinforcements to the points to which their circulation tends; 2. Another was in the examination of Mr. Biddle, president of the bank, by the investigating committee, in 1832, in which this absorbing tendency of the branch paper to flow to the Northeast was fully charged and admitted; 3. A third was in the monthly statement of the notes in transitu, which amount to an average of four millions and a half for the last twelve months, making fifty millions for the year; and which consist, by far the greater part, of branch notes and checks redeemed in the Northeast, purchased back by the branches, and on their way back to the place from which they issued; and, 4. The last class of proof was in the fact, that the branches north of the Potomac, being unable or unwilling to redeem these notes any longer, actually ceased to redeem them last fall, even when taken in revenue payment to the United States, until coerced by the Secretary of the Treasury; and that they will not be redeemed for individuals now, and are actually degenerating into a mere local currency. Upon these proofs and arguments, Mr. B. rested his case, and held it to be fully established first, by argument, founded in the nature of bank circulation over an extended territory; and secondly, by proof, derived from the operation of the present bank of the United States, that neither the present bank, nor any one that the wisdom of man can devise, can ever succeed in diffusing a general paper circulation over the States of this Union.

VI. Dropping every other objection to the bank – looking at it purely and simply as a supplier of national currency – he, Mr. B., could not consent to prolong the existence of the present bank. Certainly a profuse issue of paper at all points – an additional circulation of even a few millions poured out at the destitute points – would make currency plenty for a little while, but for a little while only. Nothing permanent would result from such a measure. On the contrary, in one or two years, the destitution and distress would be greater than it now is. At the same time, it is completely in the power of the bank, at this moment, to grant relief, full, adequate, instantaneous relief! In making this assertion, Mr B. meant to prove it; and to prove it, he meant to do it in a way that it should reach the understanding of every candid and impartial friend that the bank possessed; for he meant to discard and drop from the inquiry, all his own views upon the subject; to leave out of view every statement made, and every opinion entertained by himself, and his friends, and proceed to the inquiry upon the evidence of the bank alone – upon that evidence which flowed from the bank directory itself, and from the most zealous, and best informed of its friends on this floor. Mr. B. assumed that a mere cessation to curtail discounts, at this time, would be a relief – that it would be the salvation of those who were pressed – and put an end to the cry of distress; he averred that this curtailment must now cease, or the bank must find a new reason for carrying it on; for the old reason is exhausted, and cannot apply. Mr. B. then took two distinct views to sustain his position: one founded in the actual conduct and present condition of the bank itself, and the other in a comparative view of the conduct and condition of the former Bank of the United States, at the approaching period of its dissolution.

I. As to the conduct and condition of the present bank.

Mr. B. appealed to the knowledge of all present for the accuracy of his assertion, when he said that the bank had now reduced her discounts, dollar for dollar, to the amount of public deposits withdrawn. The adversaries of the bank said the reduction was much larger than the abstraction; but he dropped that, and confined himself strictly to the admissions and declarations of the bank itself. Taking then the fact to be, as the bank alleged it to be, that she had merely brought down her business in proportion to the capital taken from her, it followed of course that there was no reason for reducing her business any lower. Her relative position – her actual strength – was the same now that it was before the removal; and the old reason could not be available for the reduction of another dollar. Next, as to her condition. Mr. B. undertook to affirm, and would quickly prove, that the general condition of the bank was better now than it had been for years past; and that the bank was better able to make loans, or to increase her circulation, than she was in any of those past periods in which she was so lavishly accommodating the public. For the proof of this, Mr. B. had recourse to her specie fund, always the true test of a bank's ability, and showed it to be greater now than it had been for two years past, when her loans and circulation were so much greater than they are now. He took the month of May, 1832, when the whole amount of specie on hand was $7,890,347 59; when the net amount of notes in circulation was $21,044,415; and when the total discounts were $70,428,070 72: and then contrasted it with the condition of the bank at this time, that is to say, in the month of February last, when the last return was made; the items stands thus: specie, $10,523,385 69; net amount of notes in circulation, $19,260,472; total discounts, $54,842,973 64. From this view of figures, taken from the official bank returns, from which it appeared that the specie in the bank was nearly three millions greater than it was in May, 1832, her net circulation nearly two millions less, and her loans and discounts upwards of fifteen millions less; Mr. B. would submit it to all candid men to say whether the bank is not more able to accommodate the community now than she was then? At all events, he would demand if she was not now able to cease pressing them?