полная версия

полная версияA Brief History of Forestry.

Nevertheless, the court proceedings in forest matters still vary from the usual court practice, providing a simpler, cheaper and more ready disposal of testimony and witnesses, and quicker retribution, which is largely rendered possible through having every forest officer under oath as a sheriff, and his statement, and perhaps the confiscated tools employed in the theft, being accepted as prima facie evidence of the infraction.

The social position of the underforesters and the forest protective service has also been improved until all charges of incompetency and immorality, which were not undeserved even until past the middle of the nineteenth century, have become reversed; the forest service being morally on as high a plane as all the departments of German administrations.

7. Forest Policy

During the first half of the century the old conception of Forsthoheit– superior right of the princes to supervise and interfere with private property – changed into the more modern conception of the police function of the state, and, by 1850, after the revolutionary period, the seignorage of the princes had passed away. The issue of forest ordinances (the last in 1840) was replaced by the enactment of forest laws which, since the establishment of representative government, has become a function of legislatures.

The tendency to restrict the exercise of private property rights had been assailed by the theories of Laissez faire and the teachings of Adam Smith, and, as a consequence, all the restrictive mandates of the older forest ordinances had been weakened and had more of less fallen into disuse. Especially the attempts to influence prices and markets had nearly if not entirely vanished during the first decade. Only for the state forest, it was still thought desirable to predetermine wood prices, or at least keep rates low, because wood was a necessary material for the industries. This theory prevailed until, perhaps under the lead of Hundeshagen (see above), the propriety of securing the highest soil rent was recognized as the proper aim, when the practice of selling wood at auction in order to secure the best prices became the rule.

The regulations regarding export and import between the different States, which had been enacted under the mercantilistic teachings of the last century (see page 52), and the many tariffs which impeded a free exchange of commodities, lasted for a long while into the 19th century, and were not all abolished until 1865, when under the lead of Prussia, the North German Federation instituted the Zollverein (Tariff alliance) which abolished not only all tariffs between the States of the Federation, but also tariffs on wood products against the outside world. Import duties were, however, again established in 1879, and the policy of protecting the established organized forest management against competition by importations from exploiting countries has been again and again recognized as proper in the revision of tariff rates and railroad freight rates on the government railroads.

During the first decades of the century, the supply question was uppermost, and although such men as Pfeil (1816) laughed at the idea of a wood famine, there was good reason, prior to the development of railroads, of coal fields, of iron and steel manufactures, etc., for discussing with apprehension the area and condition of supply and the extent of the consumption. Nevertheless, the attitude of the state toward private property was much more influenced by the economic theories then prevalent, which taught the ideas of private liberty to which the French Revolution had given such forcible expression.

With the change of municipal communities from mere associations with common material interest into units or parts of political or state machines, also independence in the management of their property was secured, and many of the old restrictions which had circumscribed this right fell away. Curiously enough, during the French domination under Napoleon, the new masters, forgetting the spirit of the revolutionary period, introduced the prescriptions of the old French ordinance of 1669 which restricted the use of communal property to the extent of excluding the owners entirely from the management of their property, and placed it under government officers. After the French withdrew, this method, of course, collapsed, although it probably had an influence on the final shaping of forest policies in these respects. Altogether, there was such variety of historic development in the different parts of Germany that it is not to be wondered at that one finds a great variety of policies still prevailing not only in different States but in different localities of the same State.

At the present time three different principles in the relations of the state to the corporation forests may be recognized, namely, entire freedom, excepting so far as general police laws apply, which is the case with most of the corporation forests in Prussia (law of 1876); special supervision of the technical management under approved officials with proper education, which is the case in Saxony, most of Bavaria, the Prussian provinces of Westphalia, Rhineland and Saxony, and in some of the smaller states; or lastly, the absolute administration by the state, which prevails in Baden, parts of Bavaria, provinces Hesse-Nassau, and Hanover. The tendency, however, in modern times appears to be toward a more strict interpretation of the obligation of the state to prevent mismanagement of the communal property.

Private forest property, which during the preceding century had been largely under restrictions, first under the application of the hunting right, and then under the fear of a wood famine, became in the first decades of the century under the influences already mentioned, almost entirely free, all former policies being reversed; indeed Prussia, in 1811, issued an edict insuring absolutely unrestricted rights to forest owners, permitting partition and conversion of forest properties, and even denying in such cases the right of interference on the part of possessors of rights of user.

This policy of freedom was also applied, although less radically, in Bavaria, except as to smaller owners. The result was, to a large extent, the increase of exploitation and forest devastation, creating wastes and setting shifting sand and sanddunes in motion. The reaction, which set in against this unrestricted use of forest property, resulted in Prussia not in renewal of restrictive measures, but in the enactment of promotive ones. The law of 1875 sought improvement by encouraging small owners to unite their properties under one management; but the expectations which were founded on this ameliorative policy seem so far not to have been realized.

This promotive policy has especially since 1899 found expression in the institution in many provinces of information bureaus, which give technical advice, make working plans, secure plant material and give other assistance to woodland owners.

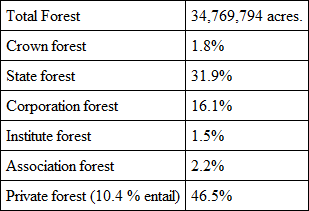

A new relation, however, of a conservative character arose by the establishment of the entail, i.e., a contract made by the head of the family with the government under which the latter assumes the obligation of forever preventing the heirs from disposing of, diminishing, or mismanaging their property. As a result of this arrangement, many of the larger private forest properties are forced to a conservative management, not as a direct influence of the law, but as a matter of agreement. The condition of state supervision of private and communal forest property at present prevailing is expressed in the following statement of divisions by property classes of forest areas of Germany, which shows that at least 63.9 % are under conservative management:

Until the beginning of the present century, the protective function of the forest had played no role in the arguments for state interference, but just about the beginning of the century cries were heard from France that, owing to the reckless devastation of the Vosges and Jura Alps by cutting, by fires and over-grazing, brooks had become torrents, and the valleys were inundated and covered by the debris and silt of the torrents. A new aspect of the results of forest devastation began to be recognized, which found excellent expression in a memoir by Moreau de Jonnès (Brussels, 1825), on the question “What changes does denudation effect on the physical condition of the country.” This being translated into German by Wiedenmann, was widely spread, being interestingly written, although not well founded on facts of natural history and physical laws. Nevertheless, sufficient experience as regards the effect of denudation in mountainous countries had also accumulated in southwest Germany and in the Austrian Alps, and the necessity of protective legislation was recognized. This necessity first found practical expression in the Bavarian law of 1852, in Prussia in 1875, and in Württemberg in 1879. But a really proper basis for formulating a policy or argument for protective legislation outside of the mountainous country is still absent, although for a number of years attempts have been made to secure such basis.

8. Forestry Science and Literature.5

The habit of writing encyclopædic volumes, which the Cameralists and learned hunters had inaugurated in the preceding century, continued into the new one, and we find Hartig, Cotta, Pfeil and Hundeshagen each writing such encyclopædias. Carl Heyer began one in separate volumes, but completed only two of them. Even an encyclopædic work in monographs by several authors was undertaken as early as 1819 by J. M. Bechstein, who with his successors brought out fourteen volumes, covering the ground pretty fully. While in the earlier stages the meager amount of knowledge made it possible to compress the whole into small compass, the more modern encyclopædias of Lorey, Fürst and Dombrowski arose from the opposite consideration, namely, the need of giving a comprehensive survey of the large mass of accumulated knowledge.

Since 1820, monographic writings, however, became more and more the practice. Among the volumes which treat certain branches of forestry monographically, the works of the masters of silviculture, Cotta, Hartig and Heyer, based on their experiences in west and middle Germany, and of Pfeil, referring more particularly to North German conditions, were followed by the South German writers, Gwinner (1834), and Stumpf (1849). In 1855, H. Burkhardt introduced in his classic Säen und Pflanzen a new method of treatment, namely, by species, and after 1850, when the development of general silviculture had been accomplished, such treatment by species became frequent. Of more modern works on general silviculture elaborating the attempts at reform of old practices those of Gayer (1880), Wagener (1884), Borggreve (1885), Ney (1885), all writing in the same decade, are to be especially mentioned. In this connection should be also noticed Fürst’s valuable collective work on nursery practice (Pflanzenzucht im Walde, 1882).

At present the magazine literature furnishes ample opportunity to discuss the development of methods in all directions. The text books at present appearing seem to be justified by or intended mainly for the needs of the teacher and rarely for the practitioner. Such a text book is that by Weise. But the latest contributions to silvicultural literature by Wagner (1907), and Mayr (1909) are works of a new order, utilizing broader ecological knowledge.

Other branches than silviculture were similarly first treated in comprehensive volumes and then in monographic writings on special subjects of the branch. The literature on forest utilization covering the whole field, was enriched especially by Pfeil, Koenig, Gayer, and Fürst. The first investigation into the physical and technical properties of wood was conducted by G. L. Hartig himself, followed by Theodor Hartig, and the subject has been most broadly treated by H. Noerdlinger (1860). In later years, Schwappach’s investigations deserve special mention.

The question of means of transportation gradually became also a subject capable of monographic treatment and a series of books came out on locating and building forest roads. Braun issued such a book in 1855 for the plains country, and Kaiser (1873) for the mountains, also Mühlhausen (1876), who had been commissioned to locate a perfect road system over the demonstration forest at the forest academy of Muenden. Only within the last quarter of the century were railroads introduced into the economy of forest management. The first comprehensive book on the subject of logging railroads was issued by Foerster (1885), and a later one by Runnebaum. Stoetzer (1903) furnished in his compact style the latest discussion on the subject of roads and railroads.

A very comprehensive literature on the value of forest litter was brought into existence by the established usage of small farmers of supplying their lack of straw for bedding and manure by substituting the litter raked from the forest. Hartig and Hundeshagen were active in the discussion of this subject as well as almost every other forester, the discussion being, however, mainly based on opinions. But, after 1860, the subject became so important both to the poor farming population and to the forest, which was being robbed of its natural fertilizer, that a more definite basis for regulating its use was established by analysis and by experiments at the experimental stations.

With the inauguration of the various methods of forest organization described before, there naturally went hand in hand the development of methods of measurement. Better forest surveys developed rapidly, the transit generally replacing the compass and plane table. At this period the necessity for books teaching the important methods of land survey was met by Baur (1858) and by Krafft (1865). This subject does no longer occupy a place in forestry literature, the knowledge of it being taken for granted.

On the other hand the subject of forest mensuration which formerly was generally treated in connection with forest organization has developed into a branch by itself, and has been very considerably developed in its methods and instruments, making a tolerably accurate measurement of forest growth possible, although many unsolved problems are still under investigation. Still, late into the century it was customary to measure only circumferences of trees, by means of a chain or band, although an instrument for measuring diameters is mentioned by Cotta, in 1804, and by Hartig, in 1808. Schœner and Richter are in 1813 mentioned as inventors of the first “universal forest measure” or caliper. The improvement of calipers to their modern efficiency has been carried on since 1840 by Carl and Gustav Heyer and by many others until now self-recording calipers by (Reuss, Wimmenauer, etc.) have become practical instruments. For measuring the heights of trees, Hossfeld had already a satisfactory instrument in 1800; a very large number of improvements in great variety followed, with Faustmann’s mirror hypsometer probably in the lead. As a special development for measuring diameters at varying heights Pressler’s instrument should be mentioned, and a very complicated but extremely accurate one constructed by Breymann.

Various formulas for the computation of the contents of felled trees had already been developed by Oettelt and others in the eighteenth century and a formula by Huber, using the average area multiplied by length was definitely introduced in the Prussian practice in 1817. The names of Smalian, Hossfeld, Pressler and others are connected with improvements in these directions.

The idea of form factors and their use was first developed by Huber, who made three tree classes according to the length of crowns, measured the diameters six feet above ground, and used reduction factors of .75,66,50 for the three classes. But the first formula for determining form factors is credited to Hossfeld (1812). Hundeshagen and Koenig also occupied themselves with elaborating form factors. Smalian (1837) introduced the conception of the normal or true form factor relating it to the area at one-twentieth of the height. An entirely new idea has lately been introduced by Schiffel, an Austrian German, under the name of form quotient, placing two measured diameters in relation.

Volume tables giving the volumes of trees of varying diameters and height were already in use to some extent in the 18th century; Cotta gives such for beech in 1804, and, in 1817, furnished a new set of so-called normal tables which were, however, based upon the assumption of a conical form of the tree. Koenig perfected volume tables by introducing further classification into five growth classes (1813), published volume tables for beech and other species, and, in 1840, published volume tables not for single trees but for entire stands per acre classified by species, height and density; using the so-called space number which he had developed in 1835 to denote the density. It is interesting to note that these tables, which he called Allgemeine Waldschætzungstafeln, were made for the Imperial Russian Society for the Advancement of Forestry.

In 1840 and succeeding years, the Bavarian government issued a comprehensive series of measurements and a large number of form factors, which were used in constructing volume tables; these were found to be so well made and so generally applicable that they were used in all parts of Germany and, translated into meter measurement by Behm (1872), are still generally in use, although new ones based upon further measurements have been furnished by Lorey and Kuntze.

For arriving at the volume of stands, estimating was relied upon long into the nineteenth century, although Hossfeld, in 1812, introduced measuring, and the use of the formula AHF, in which A was the measured total cross-section area of the stand, H and F the height and form factors, the latter being at that time still estimated. He first made form classes for the same heights, but, in 1823, simplified the method by assuming an average form factor for the whole stand. Even in 1830, Kœnig still estimated the form factor, although he introduced the measurement of the cross-section area and determined the height indirectly as an average of measurements of several height classes, but Huber (1824) knew how to measure both the average height and form factor by means of an arithmetic sample tree. This method found entrance into the practice and held sway until about 1860, when the well-known improvements by Draudt and Urich supplanted it. These last mentioned methods have become generally used in the practice, while other methods, like R. Hartig’s and Pressler’s, have remained mainly theoretical.

The study of the increment and the making of yield tables which had been inaugurated toward the end of the last century, by Oettelt, Paulsen, Hartig, and others, was just at the end of that century placed upon a new basis through Späth (1797), who constructed the first growth curves by plotting the cubic contents of trees of different ages, and through Seutter (1799) by introducing stem analysis, on which he based his yield tables.

On the shoulders of these, Hossfeld (1823) built, when he conceived the idea of using sample plots for continued observation of the progress of increment, and he also taught the method of interpolation with limited measurements, laying the basis for quite elaborate formulæ. But the first normal yield tables, based on the average trees of an index stand, were published by Huber (1824) and, in the same year, by Hundeshagen. From that time on, yield tables were constructed by many others, but only since the Experiment stations undertook to direct their construction is the hope justified of securing this most invaluable tool of forest management in reliable and sufficiently detailed form. Even the newest tables are, however, still deficient, especially in the direction of detailed information regarding the division into assortments. The yield tables of Baur, Kuntze, Weise, Lorey, and others are now superseded by those of Schwappach for pine and spruce, and of Schuberg for fir.

As a result of the many yield tables which gradually accumulated, the laws of growth in general became more and more cleared up and finally permitted their formulation as undertaken by R. Weber (Forsteinrichtung, 1891).

The idea of using the percentic relations for stating the increment, and of estimating the future growth upon the basis of past performance for single trees was known even to Hartig (1795) and Cotta (1804) who published increment per cent. tables. The methods of making the measurements of increment on standing trees were especially elaborated by Koenig, Karl, Edward and Gustav Heyer, Schneider (his formula, 1853), Jaeger, Borggreve, and especially by Pressler (1860) who opened new points of view and increased the means of studying increment by causing the construction of the well-known increment borer, and in other ways.

The most modern text-book which treats fully of all modern methods of forest mensuration giving also their history is that of Udo Müller (Lehrbuch der Holzmesskunde, 1899), superseding such other good ones, as those of Baur (1860-1882), Kuntze (1873), Schwappach (short handbook, last edition 1903).

The many sales of forest property which took place at the beginning of this period naturally stimulated the elaboration of methods of forest valuation. Even the soil rent theory finds its basis at the very beginning (1799) in a published letter by two otherwise unknown foresters (Bein and Eyber), who proposed to determine the value of a forest by discounting the value of the net yield with a limited compound interest calculation to the 120th year. This idea was elaborated, in 1805, by Nœrdlinger and Hossfeld into the modern conception of expectancy values, and the now familiar discount calculations were inaugurated by them. Cotta and Hartig participated also in the elaboration of methods of forest valuation; Cotta writing his manual in 1804, recognizes the propriety of compound interest calculations, while Hartig, 1812, still uses only simple interest, and exhibits in his book as well as in his instructions for practice in the Prussian state forests rather mixed notions on the subject.

Altogether, even in the earlier part of the period, there arose considerable difference of opinion and warm discussions, in which all the prominent foresters took part, as to the use of interest rates and methods of calculation. But this warfare broke into a red hot flame when Faustmann (1849) with much mathematical apparatus developed his formula for the soil expectancy value, and when Pressler and G. Heyer transferred the discussion into statical fields, making the question of the financial rotation the issue. Then the advocates of the soil rent and of the forest rent theories ranged themselves in opposite camps. This war of opinions, although abated in fervor, still continues, and the issue is by no means settled.

The discussion of what should be considered the proper felling age or rotation naturally occupied the minds of foresters from early times; a maximum volume production being originally the main aim. As early as 1799, Seutter had recognized the fact that the culmination of volume production had been obtained when the average accretion had culminated. Hartig, in 1808, made the distinction of a physical, an economic and a mercantilistic, i.e., financial felling age, and Pfeil, considerably ahead of his time, is the first to call (1820) for a rotation based on maximum soil rent. As, however, he had so often done, he changed his mind, and while he first advocated even for the state a management for the highest interest on the soil capital involved, he later rejected such money management. About the same time Hundeshagen clearly pointed out the propriety and proper method of basing the rotation on profit calculations, but it was reserved for a man not a forester to stir up the modern strife for the proper financial basis, namely Pressler, a professor of mathematics at Tharandt, who became a sharp critic of existing forest management, and developed to the extreme the net yield theories.