полная версия

полная версияA Brief History of Forestry.

A number of special forms of silvicultural management applicable under special conditions have been locally developed, without, however, gaining much ground and being mainly of historical value. Among these may be mentioned Seebach’s Modified Beech Forest, which consists in opening up a beech stand so as to secure regeneration, merely to form a soil cover, leaving enough of the old stand on the ground to close up in thirty or forty years. By this treatment the large increment due to open position is secured without endangering the soil. Similarly the Storied or Two-aged High forest, was applied to the management of oak forest in mixture with beech. In a few localities also, on limited areas, a combination of forest and farming (Waldfeldbau) has been continued and elaborated, besides the more general use of coppice and coppice with standards.

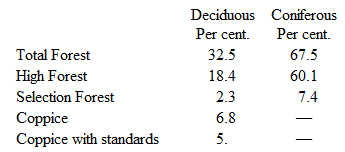

According to the statistics for 1900 the following distribution of the acreage under different silvicultural methods prevailed throughout the empire:

Coniferous forest, of which 68 % is pine and 30 % spruce, prevails in Eastern and Middle Germany, deciduous forest, of which 20 % is oak, the balance principally beech, in the West and South.

Coppice and coppice with standards are mostly in private hands as well as the coniferous selection forest, the State forests being almost entirely high forest, i.e., seed forest, other than under selection method.

Methods of Improving the Crop. The credit of having first systematically formulated the practice of thinnings under the name of Durchforstung (for the first thinning), Durchplenterung (for the later thinnings), belongs to Hartig, although the practice of such thinnings had been known and applied here and there before his time. He confined himself mainly to the removal of the undesirable species, dead and dying, suppressed and damaged trees, being especially emphatic in his advice not to interrupt the crown cover. Excepting the early weeding or improvement cuttings, these thinnings were not to begin until the fiftieth to seventieth year in the broadleaved forest, but in conifers in the twentieth to thirtieth year.

The first attempt to explain on a biological basis the process and effect of thinning was made by Späth in a special contribution (1802). Cotta, in his Silviculture, although at first agreeing with Hartig, later in his third edition (1821) changes his mind, and improves both upon the biological explanation of Späth and the practice of Hartig, pointing out that the latter came too late with his assistance, that the struggle between the individuals should be anticipated, and the thinning repeated as soon as the branches begin to die; but he also recognizes the practical difficulty of the application of this cultural measure on account of the expense. Curiously enough, he recommends severer thinnings for fuel-wood production than for timber forests.

Pfeil accentuates the necessity of treating different sites and species differently in the practice of thinnings. Hundeshagen accentuates the financial result and the fact that the culmination of the average yield is secured earlier by frequent thinnings. Heyer formulates the “golden rule:” “Early, often, moderate,” but insists that first thinning should not be made until the cost of the operation can be covered by the sale of the material. Propositions to base the philosophy and the results of thinning on experimental grounds rather than on mere opinion were made as early as 1825 to 1828, and again from 1839 to 1846, at various meetings of forestry associations, until, in 1860, Brunswick and Saxony inaugurated the first more extensive experiments in thinnings. The two representatives of forest finance, Koenig and Pressler, pointed out, in 1842 to 1859, the great significance of thinnings in a finance management as one of the most important silvicultural operations for securing the highest yield.

In spite of the advanced development of the theory of thinning, the practice has largely lagged behind, because of the impracticability of introducing intensive management. Only lately, owing to improvement in prices and the possibility of marketing the inferior material profitably enough to justify the expenditure, has it become possible to secure more generally the advantages of the cultural effect. Within the last thirty or forty years, great activity has been developed among the experiment stations in securing a true basis for the practice of thinning.

New ideas were introduced through French influence and by others independently in the latter part of the eighties, when the distinction between the final harvest crop (Fr. élite, le haut) and the nurse crop (le bas) was introduced.4

The physiological reasons for the practice of thinning upon experimental basis, were advanced by the botanists Goeppert and R. Hartig, and among foresters, the names of Kraft, Lorey, Haug, Borggreve, Wagener, and others are intimately connected with the very active discussion of the subject lately going on in the magazines. Thinnings have become such an important part of the income of forest administrations (25 to 40 % of the total yield) that the prominence given to the subject is well justified, and a more modern conception of the advantages of thinnings and especially of severer thinnings is gaining ground.

The proposition, now much ventilated, of severe opening up near the end of the rotation, in order to secure an accelerated increment (Lichtungshiebe) is, however, much older; Hossfeld, in 1824, and Jäger in 1850, advocated this measure for financial reasons, while Koenig and Pressler anticipated the development of an individual tree management by pruning, and differentiation of final harvest and nurse crop, a method which is working itself out at the present time.

5. Methods of Forest Organization

As stated before, to Hartig and Cotta belongs the credit of having applied systematically on a large scale methods of forest organization for sustained yield; Hartig having been active in Prussia since 1811, and Cotta beginning to organize the Saxon forests in the same year. The method employed by Hartig, the so-called volume allotment, had been already formulated and its foundation laid by Kregting and others (although Hartig seems to have claimed the invention). But it was reserved to Hartig to build up this method in its detail, and to formulate clearly and precisely its application, as well as to improve the practice of forest survey, calculation of increment, and the making of yield tables. His method involved a survey, a subdivision, a construction of yield tables and the formulation of working plans, in which the principle according to which the forest was to be managed during the whole rotation was laid down for each district. The rotation was determined, divided into periods, finally of twenty years, and the periodic volume yield represented by all stands was distributed through all the periods of the rotation in such a manner as to make the periodic felling budgets approximately equal; or, since the tendency to increased wood consumption was recognized, an increase of the felling budget toward the end of the rotation was considered desirable.

Cotta based his system of forest organization upon a method described by a Bavarian, Schilcher (1796); it relied primarily upon area rather than volume division. This method was later on (1817), called by him Flaechenfachwerk (area allotment). It divides the rotation into periods and allots areas for each periodic felling budget. But before this time, in 1804, Cotta had himself formulated a method of his own, which combined the area and volume method, the volume being the main basis and the area being merely used as a check. While Hartig dogmatically and persistently carried out his difficult scheme, Cotta was open-minded enough to improve his method of regulation, and by 1820, in his Anweisung zur Forst-Einrichtung und – Abschaetzung, he comes to his final position of basing the sustained yield entirely on the area allotment, using the estimate of volume simply to secure an approximately uniform felling budget. He laid particular stress on orderly procedure in the subdivision and progress of the fellings. He did not prepare an elaborate working plan binding for the entire rotation, but merely prescribed the principles of the general management, and, after 1816, he confined the formulating of felling and planting plans only to the next decade.

A similar method, making a closer combination of volume and area allotment, now known as the combined allotment, in which the area forms the main basis for distributing the felling budgets, was prescribed by Klipstein in 1833. This, also, confines the working plan to the first period of the rotation and for this period alone makes a rather careful statement of the expected volume budget; a new budget is then to be determined at the beginning of the next period. This idea of confining the budget determination to a comparatively short period is now generally accepted, the future receiving only summary consideration.

These methods of organization were the ones generally applied in practice, and are still with some modifications in practical use. About 1820, however, new theories were advanced which led to the formulation of methods based upon the idea of the normal forest. The conception of a normal forest, with a normal stock, distributed in normal age classes, so as to insure a sustained yield management, was evolved, in 1788, by an obscure anonymous official in the Tax-collector’s office of Austria, designed for assessing woods managed for sustained yield. This fertile idea, which is still the basis of forest organization in Austria, and explains better than any other method the principles involved in forest organization, did not find entrance into forestry literature in all its detail until 1811 when André compared this so-called Cameraltaxe with Hartig’s method of regulation. We find, however, that, simultaneously with the Austrian invention of this method, Paulsen (1787) proposed to determine the felling budget as a relation between normal stock and normal yield, and in his yield tables (the first of the kind, 1795), he gives the proportion of increment to normal stock in percentic relation, so that the felling budget may be either expressed as a fraction of the stock or as a per cent.; in beech forests, for instance, he determines the felling budget as 3.3 % on best sites, 2.5 % on medium, and 1.8 % on poor sites.

Probably stimulated by André’s description, Huber (1812) developed a method and formula which may be considered the foundation of the later development by Carl Heyer

Based upon the normal forest idea, a number of methods were elaborated which, because of their employing a mathematical formula for the determination of the felling budget, are known as formula methods; they are, indeed modified rational volume divisions.

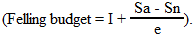

Hundeshagen has the merit of having first clearly explained the basis of these methods, and himself developed a formula, of the correctness of which he was so convinced as to designate his method as “the rational” one. Two other formulæ were brought into the world by Koenig (1838-1851), but the credit of the most complete elaboration both of the principles of the normal forest idea and of its practical application belongs to Carl Heyer. The principles of his method are briefly: First determine upon the period of regulation during which the abnormal forest is to be brought nearer to normal conditions; the length of this period to be determined with due regard to the financial requirements or ability of the owner and to the conditions of the forest. The actual stock on hand is then determined and the total increment, based on the average increment at felling age of each stand, which will take place during this period, is added. Deducting from this total what has been calculated as the proper normal stock requisite for a sustained yield management, the balance is available for felling budgets which may be utilized in annual or periodic instalments during the period of regulation. A working plan is provided which takes care of securing an orderly progress of fellings and proper location of age classes, to be revised every ten years.

Although this is undoubtedly the most rational method yet devised, it has remained largely unused, and is found in somewhat modified application only in Austria and Baden.

An entirely new principle in the theory of forest organization was introduced, when the aim of forest management was formulated to be the highest soil rent. According to this requirement the proper harvest time of any stand, or even of any tree, was to be determined by the so-called index per cent., that is, a calculation which determines whether a stand or a tree is still producing at a proper predetermined rate, or is declining. The advocates of this principle were especially Pressler (professor of mathematics at Tharandt, 1840 to 1843) and G. Heyer, son of Carl Heyer, who based his method on his father’s formula, merely introducing values for volumes. Judeich, director of the Tharandt school, also developed in the sixties a method, based upon financial theory, which is to attain the highest rate per cent. on the capital invested in forest production. On the basis of survey and subdivision of working blocks composing a felling series, and with a rotation determined by financial calculations with interest accounts, he makes a periodic area division for determining the felling budget in general, and in addition employs the index per cent., as explained, for determining in each allotted stand the more exact time for its harvest.

While these men pleaded for a strict finance calculation, such as is properly applied to any business making financial results the main issue, the defenders of the old regime, which sought the object of forest management mainly in highest material or value production, advanced as their financial program the attainment of the highest forest rent as opposed to the highest soil rent. They neglected and derided the complicated interest calculations which have to take into consideration uncertain future developments, and were satisfied with producing a satisfactory balance, a surplus of income over expenses, no matter what interest rate on the capital involved in soil and forest growth that might represent.

At the present time these financial propositions are still mainly under heated discussion.

In actual practice, the various state forest administrations, with the exception of the Saxon one, continue to rely upon the older methods in regulating the management of their forest properties without reference to financial theories. This is largely due to momentum of the practical existence and application of these methods in earlier times and the difficulty and impracticability of a change. Just now, however, several of the State administrations are preparing to radically revise their working plans.

In Prussia, the instructions for working plans of 1819 formulated by Hartig were improved upon by his successor, Oberlandforstmeister von Reuss (1836), and these instructions formed the basis of the work of forest regulation until the end of the 19th century. It is a periodic area allotment with only a summary check by volume. The working plan is only to secure a rational location and gradation of age classes; the calculations of yields and specific rules of management are lately confined to the first period and are revised every six years.

In Saxony, Cotta’s area method was systematically developed, and, as the larger part of Saxon forests is coniferous, mainly spruce, the proper location of age classes forms a special consideration for the progress of fellings. The determination of volume and increment was left to summary estimates, and the area division became entirely superior. The original idea of Cotta that orderly procedure in the management is of more importance than the actual determination and equalization of yield still pervades the Saxon practice. Since 1860, an attempt has been made to calculate the rotation and determine the felling budget on the principle of the soil rent, at least as a corrective of the annual budget, and in general to lean towards Judeich’s stand management.

In Bavaria, after various changes, a complete allotment method of area and volume had come into vogue, in 1819; but, at the present writing (1911) an entirely new and modern re-organization has been begun, in which most modern ideas and especially much freedom of movement, even to deviation from the principle of sustained yield, is allowed.

In Württemberg, where, in 1818 to 1822, a pure volume allotment had been introduced, in 1862 to 1863 the combined allotment method was begun, the felling budget being determined in a general way for the next two or three periods, and more precisely for the first decade, without attempting more than approximate equality.

In 1898, new instructions were issued, which abandon the allotment method and restrict the yield regulation to designating felling areas for the first period.

In Baden, where the forest organization began in 1836 upon the basis of volume allotment, a change was made in 1849 to an area allotment, simplifying to a greater extent than anywhere else the calculation of the yield; finally, Heyer’s method was adopted entirely in 1869.

It appears then that the schematic allotment methods found the most general application in the earlier time of the period, being favored probably on account of their simplicity in application. The improvement in their present application over the original methods as designed by Hartig and Cotta, is that now they require no volume calculation for any long future, but are satisfied with making a sufficiently accurate calculation and provision for the proper felling budget for the present.

6. Forest Administration

About the middle of the 18th century the recognition of the importance of forestry led to a severance of the forest and hunting interests, and it became the practice to place the direction of the former into the hands of some more or less competent man – a state forester – usually under the fiscal branch or treasury department of the general administration. Fully organized forest administrations, in the modern sense, however, could hardly be said to have existed before the end of the Napoleonic wars (1815) which had undoubtedly retarded the peaceful development of this as well as of other reforms.

The present organization of the large Prussian forest department in its present form dates from 1820, when Hartig instituted the division into provincial administrations, and differentiated them into directive, inspection and executive services. The direction of the provincial management was placed in the hands of an Oberforstmeister, with the assistance of a number of Forstmeister, who acted mainly as inspectors, each having his inspection district consisting of a number of ranges. The ranges (100,000 to 125,000 acres) were placed in charge of Oberförster or Revierförster, who with the assistance of several underforesters (Förster) conducted the practical work. At first only indifferently educated, these latter were allowed little latitude, but with improvement in their education they became by degrees more and more independent agents.

This tri-partite system of directing, inspecting and executive officers, after various changes in titles and functions, finally became practically established in all the larger German states; in some rather lately, as for instance, in Bavaria, not until 1885, and in Württemberg in 1887.

With this more stable organization, the character and the status of the personnel changed greatly: the prior right of the nobility to the higher positions, which had lasted in some States until 1848, and the practice of making connection with military service a basis for appointment were abolished, and, instead of Cameralists, educated foresters came everywhere to the head of affairs. The lower service, which had been recruited from hunters and lackeys, and which was noted for its low social, moral and pecuniary status, was improved in all directions. The change from incidentals in the way of fees, and natural instead of money emolument for the lower grade foresters, (which had been the rule, and still play a role even to date), to definite salaries, and the salutary change of methods in transacting business, which Hartig introduced, became general. With the development and improvement of forestry schools, the requirement of a higher technical education for positions in State service could be enforced. Yet only within the last twenty-five or thirty years, has the ranking position of forest officers been made adequate and equalized with that of other public officials of equal responsibility, and still later have their salaries been made adequate to modern requirement.

The central administration now lies in the hands of technical men (Oberlandforstmeister) with a council of technical deputies (Landforstmeister) all of whom have passed through all the stages of employment from that of district managers up. This central office or “division of forestry” is either attached to the department of agriculture, or to that of finance, and has entire charge of the questions of personnel, direction of forest schools, of the forest policy of the administration, and the approval of all working plans, acting in all things pertaining to the forest service as a court of last resort. The working plans are made and revised by special commissioners in each case, or, as in Saxony, under the direction of a special bureau, with the assistance of the district manager. Upon the basis of the general working plan prepared by these commissions, an annual plan is elaborated by the district managers with consultation and approval of the provincial and central administration. These plans contain a detailed statement of all the work to be done through the year, the cost of each item, and the receipts expected from each source. This annual working plan requires approval by the provincial administration, which is constituted as a deliberative council, consisting of a number of Forstmeister with an Oberforstmeister as presiding officer. The titles of these officers, to be sure, and the details of procedure vary somewhat in different states, but the system as a whole is more or less alike.

The district manager or Oberförster, now often called Forstmeister, has grown in importance and freedom of position, although his district has grown smaller (mostly not over 25,000 acres), and, being one of the best educated men in the country district, he usually holds the highest social position, although his emoluments are still moderate. He holds many offices of an honorary character, as for instance that of justice of the peace, and the position of states’ attorney or public prosecutor in all cases of infraction of the forest laws. These forest laws are still largely local, i. e., State laws, although the criminal code of the empire has somewhat unified practice.

Curiously enough, wood on the stump is still not considered property in the same sense as other things, so far as theft is concerned; the stealing of growing timber is not even called theft, the word used in the laws being Frevel (tort), and, like other infractions against forest laws, it is punished by a money fine, more or less in proportion to the value of the stolen material or the damage suffered. This money fine may be transmuted into imprisonment or forest labor, but corporal punishment, which still prevailed in the first decades of the century, has been abolished. Wood stealing was very general and rampant during the beginning of the century, but improvement in the condition of the country population and in the number and personnel of the forest officers since 1850 has now reduced it to a minimum.

Formerly, and until 1848, the administrators and even the forest owners acted at the same time as prosecutor, judge and executioner, and only in 1879, was this condition everywhere and entirely changed, and infractions against forest laws adjudged by regular courts of law, holding meetings at stated times for the prosecution of such infractions.