полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

‘Volunteer cavalry to the left; Irregular cavalry to the right: – Captain Barrow to command.

‘ENGINEER DEPARTMENT‘Chief-engineer, Captain Crommelin; assistant-engineers, Lieutenants Leonard and Judge.

‘Major-general H. Havelock, C.B., to command the force.’

Officers Wounded.– Major-general Sir J. Outram; Lieutenant-colonel Tytler; Captains Becher, Orr, Hodgson, Crommelin, Olphert, L’Estrange, Johnson, Lockhart, Hastings, and Willis; Lieutenants Sitwell, Havelock, Lynch, Palliser, Swanston, Birch, Crowe, Swanson, Grant, Jolly, Macpherson, Barry, Oakley, Woolhouse, Knight, Preston, Arnold, and Bailey. Some of the wounded officers afterwards died of their wounds.

52

The Queen afterwards gave to the brigadier-general’s wife the title which she would have acquired in the regular way if her gallant husband had lived a few weeks longer – that of Lady Neill.

53

Officers Killed.– Brigadier-general Neill; Brigade-major Cooper; Lieutenant-colonel Bazely; Captain Pakenham; Lieutenants Crump, Warren, Bateman, Webster, Kirby, Poole, and Moultrie.

54

55

H.M. 5th Fusiliers, 137 men, under Captain L’Estrange; H.M. 10th foot, 197 men, under Captain Patterson; Sikh battalion, 150 men, under Mr Wake, of Arrah celebrity; mounted volunteers, 16, under Lieutenant Jackson.

56

Chaps. ix., x., xi.: pp. 147-191.

57

‘On the morning of the 18th they were not a mile off, so at noon we marched through the city to meet them. Our force consisted of 160 sepoys and 100 irregular cavalry or sowars, one six-pounder, and eight men to work it. This gun was an old one that had been put up to fire every day at noon. I rigged it out with a new carriage, made shot and grape, and got it all in order. With my gun I kept the fellows in front in check; but there were too many of them. There were from 2500 to 3000 fighting-men, armed with matchlocks and swords, and many thousands who had come to plunder. They outflanked us on both sides, and the balls came in pretty fast. Men and horses were killed by my side, but, thank God, I escaped unhurt! We retired through the city to our intrenchments, followed by the enemy. They made several attacks, coming up every time within a hundred yards; but they could not stand the grape. At five P.M. they made their last attempt; but a lucky shot I made with the gun sent them to the right-about. They lost heart, and were seen no more. We killed from 150 to 200 of them, our own loss being 18 killed and wounded, and eight horses. All their wounded and a lot of others were cut up during their retreat by the rascally villagers, who would have done the same to us had the day gone against us. Our victory was complete. Not a house in Azimghur was plundered, and the whole of the rebels have since dispersed. Please God, as soon as I hear of Lucknow being relieved, I’ll be after them again. They have paid me the compliment of offering five hundred rupees for my head.’

58

‘In the evening there was a fearful though causeless panic at Rajghat, where the intrenchment is being made. The cry arose: “The enemy are coming.” The workmen, 3000 in number, rushed down the hill as for their lives. Prisoners who were at work tried to make their escape, and were with difficulty recovered. Gentlemen ran for their rifles; the soldiers got under arms; the gunners rushed to their guns; and altogether, there was indescribable confusion and terror. All this was the result of a succession of peals of thunder, which were mistaken for the firing of artillery!’

59

Chapter xi., pp. 177-181.

60

61

62

Chapter xii., pp. 193-205.

63

Chapter xi., pp. 176-190.

64

‘We were still looking at the scene and speculating upon the tenants of the tombs, when an old Mussulman came near us with a salam; he accosted us, and I asked him in whose honour the tomb had been erected. His reply struck me at the time as rather remarkable. “That,” said he, pointing to the largest, “is the tomb of the Nawab Mustapha; he reigned about 100 years ago: and that,” pointing to a smaller mausoleum near it, “is the tomb of his dewan, and it was he who counselled the nawab thus: ‘Beware of the French, for they are soldiers, and will attack and dispossess you of your country; but cherish the Englishman, for he is a merchant, and will enrich it.’ The nawab listened to that advice, and see here!” The old man was perfectly civil and respectful in his manner, but his tone was sad: it spoke the language of disappointment and hostility, if hostility were possible. In this case the man referred to our late assumption of the Carnatic, upon the death of the last nawab, who died without issue. As a general rule, never was a conquered country so mildly governed as India has been under our rule; but you can scarcely expect that the rulers we dispossessed, even though like ourselves they be foreigners, and only held the country by virtue of conquest, will cede us the precedence without a murmur.’

65

‘My Lord – We, the undersigned inhabitants of Bombay, have observed with sincere regret the late lamentable spread of mutiny and disaffection among the Bengal native soldiery, and we have read with feelings of horror and indignation the accounts of the cowardly and savage atrocities perpetrated by the ruthless mutineers on such unfortunate Europeans as fell into their hands.

‘While those who have ever received at the hands of government such unvarying kindness and consideration have proved untrue to their salt and false to their colours, it has afforded us much pleasure to observe the unquestionable proof of attachment manifested by the native princes, zemindars, and people of Upper India in at once and unsolicited rallying around government and expressing their abhorrence of the dastardly and ungrateful conduct of the insurgent soldiery. Equally demanding admiration are the stanchness and fidelity displayed by the men of the Bombay and Madras armies.

‘That we have not earlier hastened to assure your lordship of our unchangeable loyalty, and to place our services at the disposal of government, has arisen from the entire absence in our minds of any apprehension of disaffection or outbreak on this side of India.

‘We still are without any fears for Bombay; but, lest our silence should be misunderstood, and with a view to allay the fears which false reports give rise to, we beg to place our services at the disposal of government, to be employed in any manner that your lordship may consider most conducive to the preservation of the public peace and safety.

‘We beg to remain, my lord, your most obedient and faithful servants,

‘Nowrojee Jamsetjee, &c., &c.’

66

Chapter vii., p. 111; chapter xi., pp. 181-189.

67

Chap. xiv., pp. 230-246.

68

By comparing two wood-cuts – ‘Bird’s-eye View of Delhi’ (p. 64), and ‘Delhi from Flagstaff Tower’ (p. 76) – the reader will be assisted in forming an idea of the relative positions of the mutineers within the city, and of the British on the ridge and in the camp behind it. The ‘Bird’s-eye View’ will be the most useful for this purpose, as combining the characteristics of a view and a plan, and shewing very clearly the river, the bridge of boats, the camp, the ridge, the broken ground in front of it, the Flagstaff Tower, Metcalfe House, the Custom-house, Hindoo Rao’s house, the Samee House, the Selimgurh fort, the city, the imperial palace, the Jumma Musjid, the walls and bastions, the western suburbs, &c.

69

70

H.M. 52d light infantry.

35th Bengal native infantry.

2d Punjaub infantry.

9th Bengal native cavalry, one wing.

Moultan horse.

Dawe’s troop of horse-artillery.

Smyth’s troop of native foot-artillery.

Bourchier’s light-infantry battery.

71

During that famous pursuit and defeat of the Sealkote mutineers, a wing of H.M. 52d foot marched sixty-two miles in forty-eight hours of an Indian summer, besides fighting with an enemy who resisted with more than their usual determination. It was work worthy of a regiment which had marched three thousand miles in four years.

72

‘What a sight our camp would be even to those who visited Sebastopol! The long lines of tents, the thatched hovels of the native servants, the rows of horses, the parks of artillery, the English soldier in his gray linen coat and trousers (he has fought as bravely as ever without pipeclay), the Sikhs with their red and blue turbans, the Afghans with their red and blue turbans, their wild air, and their gay head-dresses and coloured saddle-cloths, and the little Goorkhas, dressed up to the ugliness of demons in black worsted Kilmarnock hats and woollen coats – the truest, bravest soldiers in our pay. There are scarcely any Poorbeahs (Hindustanis) left in our ranks, but of native servants many a score. In the rear are the booths of the native bazaars, and further out on the plain the thousands of camels, bullocks, and horses that carry our baggage. The soldiers are loitering through the lines or in the bazaars. Suddenly the alarm is sounded. Every one rushes to his tent. The infantry soldier seizes his musket and slings on his pouch, the artilleryman gets his guns harnessed, the Afghan rides out to explore; in a few minutes everybody is in his place.

‘If we go to the summit of the ridge of hill which separates us from the city, we see the river winding along to the left, the bridge of boats, the towers of the palace, and the high roof and minarets of the great mosque, the roofs and gardens of the doomed city, and the elegant-looking walls, with batteries here and there, the white smoke of which rises slowly up among the green foliage that clusters round the ramparts.’

73

‘The first day we marched to a place called Khurkowdeh, but such a march! We had to go through water for miles up to the horses’ girths. We took Khurkowdeh by surprise, and Hodson immediately placed men over the gates, and we went in. Shot one scoundrel instanter, cut down another, and took a ressaldar (native officer) and some sowars (troopers) prisoners, and came to a house occupied by some more, who would not let us in at all; at last, we rushed in and found the rascals had taken to the upper story, and still kept us at bay. There was only one door and a kirkee (window). I shoved in my head through the door, with a pistol in my hand, and got a clip over my turban for my pains; my pistol missed fire at the man’s breast (you must send me a revolver), so I got out of that as fast as I could, and then tried the kirkee with the other barrel, and very nearly got another cut. We tried every means to get in, but could not, so we fired the house, and out they rushed a muck among us. The first fellow went at – , who wounded him, but somehow or other he slipped and fell on his back. I saw him fall, and, thinking he was hurt, rushed to the rescue. A Guide got a chop at the fellow, and I gave him such a swinging back-hander that he fell dead. I then went at another fellow rushing by my left, and sent my sword through him, like butter, and bagged him. I then looked round and saw a sword come crash on the shoulders of a poor youth; oh, such a cut; and up went the sword again, and the next moment the boy would have been in eternity, but I ran forward and covered him with my sword and saved him. During this it was over with seven men. – had shot one with his revolver, and the other four were cut down at once. Having polished off these fellows, we held an impromptu court-martial on those we had taken, and shot them all – murderers every one, who were justly rewarded for their deeds.’

74

Captain (now Major) Olphert being ill, the command of his troop was taken by Captain Remington.

75

‘Mrs – , the wife of Mr – , made her escape from Delhi on the morning of the 19th. Poor creature, she was almost reduced to a skeleton; as she had been kept in a sort of dungeon while in Delhi. Two chuprassees, who, it appears, have all along been faithful to her, aided her in making her attempt to escape. They passed through the Ajmeer Gate, but not wholly unobserved by the mutineers’ sentries, as one of the chuprassees was shot by them. It being dark at the time, she lay hidden among the long web-grass until the dawn of day, when she sent the chuprassee to reconnoitre, and as luck would have it, he came across the European picket stationed at Subzee Mundee. So soon as he could discover who they were, he went and brought the lady into the picket-house amongst the soldiers, who did all they could to insure her safety. As soon as she arrived inside the square, she fell down upon her knees, and offered up a prayer to Heaven for her safe deliverance. All she had round her body was a dirty piece of cloth, and another piece folded round her head. She was in a terrible condition; but I feel assured that there was not a single European but felt greatly concerned in her behalf; and some even shed tears of pity when they heard the tale of woe that she related. After being interrogated by the officers for a short time, Captain Bailey provided a doolie for her, and sent her under escort safe to camp, where she has been provided with a staff-tent, and everything that she requires.’

76

77

78

One of the writers remarked: ‘The stout rope-mat which forms an efficient screen to the Russian artillerymen while serving their gun, impervious to the Minié ball, which lodges harmlessly in its rough and rugged surface, may surely suggest to our engineers the expediency of some effort to shield the valuable lives of our men when exposed to the enemy’s fire. In ancient warfare, all nations appear to have defended themselves from the deadly arrow by shields, and why the principle of the testudo should be ignored in modern times is not obvious. Take the instance before us – Lieutenant Salkeld and a few others undertake the important, but most perilous duty of blowing in the Cashmere Gate, by bags of gunpowder, in broad daylight, and in the face of numerous foes, whose concentrated fire threatens the whole party with certain death. It is accomplished, but at what a loss! Marvellous indeed was it that one escaped. Now, as a plain man, without any scientific pretensions, I ask, could not, and might not, some kind of defensive screen have been furnished for the protection of these few devoted men? Suppose a light cart or truck on three wheels, having a semicircular framework in front, against which might be lashed a rope-matting, and inside a sufficient number of sacks of wool or hay, propelled by means of a central cross-bar pushed against by four men within the semicircle, the engineers could advance, and on reaching the gate, perform their work through a central orifice in the outer matting, made to open like a flap. The party would then retire in a similar manner, merely reversing the mode of propulsion, until the danger was past.’ Another, Mr Rock of Hastings, said: ‘In July 1848, I sent a plan for a movable shield for attacking barricades, to General Cavaignac, at Paris; and on the 13th or 14th of July your own columns (the Times) contained descriptions of my machine, and a statement by your Paris correspondent that it had been constructed at the Ecole Militaire in that city. Fortunately, it was never used there, but there seems to me no valid reason why such a contrivance should not be used on occasions like that which recently occurred at Delhi. The truck proposed, with a shield in front, would serve to carry the powder-bags, without incurring the chance of their being dropped owing to the fall of one or two of the men employed on the service, while the chances of premature ignition would be diminished. These, I think, are advantages tending to insure success which should induce military engineers to use movable cover for their men when possible, even if they despise it as a personal protection.’

79

When the magazine was so heroically fired by Lieutenant Willoughby, four months earlier, the destruction caused was very much smaller than had been reported and believed. The stores in the magazine had been available to the rebels during the greater part of the siege.

80

81

‘The force assembled before Delhi has had much hardship and fatigue to undergo since its arrival in this camp, all of which has been most cheerfully borne by officers and men. The time is now drawing near when the major-general commanding the force trusts that their labours will be over, and that they will be rewarded by the capture of a city for all their past exertions and for a cheerful endurance of still greater fatigue and exposure… The artillery will have even harder work than they yet have had, and which they have so well and cheerfully performed hitherto; this, however, will be for a short period only, and when ordered to the assault, the major-general feels assured British pluck and determination will carry everything before them, and that the blood-thirsty and murderous mutineers against whom they are fighting will be driven headlong out of their stronghold or be exterminated.

‘Major-general Wilson need hardly remind the troops of the cruel murders committed on their officers and comrades, as well as their wives and children, to move them in the deadly struggle. No quarter should be given to the mutineers; at the same time, for the sake of humanity, and the honour of the country they belong to, he calls upon them to spare all women and children that may come in their way… It is to be explained to every regiment that indiscriminate plunder will not be allowed; that prize-agents have been appointed, by whom all captured property will be collected and sold, to be divided, according to the rules and regulations on this head fairly among all men engaged; and that any man found guilty of having concealed captured property will be made to restore it, and will forfeit all claims to the general prize; he will also be likely to be made over to the provost-marshal, to be summarily dealt with.’

82

‘The reports and returns which accompany this dispatch establish the arduous nature of a contest carried on against an enemy vastly superior in numbers, holding a strong position, furnished with unlimited appliances, and aided by the most exhausting and sickly season of the year.

‘They set forth the indomitable courage and perseverance, the heroic self-devotion and fortitude, the steady discipline, and stern resolve of English soldiers.

‘There is no mistaking the earnestness of purpose with which the struggle has been maintained by Major-general Wilson’s army. Every heart was in the cause; and while their numbers were, according to all ordinary rule, fearfully unequal to the task, every man has given his aid, wherever and in whatever manner it could most avail, to hasten retribution upon a treacherous and murderous foe.

‘In the name of outraged humanity, in memory of innocent blood ruthlessly shed, and in acknowledgment of the first signal vengeance inflicted upon the foulest treason, the governor-general in council records his gratitude to Major-general Wilson and the brave army of Delhi. He does so in the sure conviction that a like tribute awaits them, not in England only, but wherever within the limits of civilisation the news of their well-earned triumph shall reach.’

Some days afterwards, Lord Canning issued a more formal and complete proclamation, of which a few paragraphs may here be given: ‘Delhi, the focus of the treason and revolt which for four months have harassed Hindostan, and the stronghold in which the mutinous army of Bengal has sought to concentrate its power, has been wrested from the rebels. The king is a prisoner in the palace. The head-quarters of Major-general Wilson are established in the Dewani Khas [the “Elysium” of the Mogul palace-builders, and of Moore’s Lalla Rookh]. A strong column is in pursuit of the fugitives.

‘Whatever may be the motives and passions by which the mutinous soldiery, and those who are leagued with them, have been instigated to faithlessness, rebellion, and crimes at which the heart sickens, it is certain that they have found encouragement in the delusive belief that India was weakly guarded by England, and that before the government could gather together its strength against them, their ends would be gained.

‘They are now undeceived.

‘Before a single soldier of the many thousands who are hastening from England to uphold the supremacy of the British power has set foot on these shores, the rebel force, where it was strongest and most united, and where it had the command of unbounded military appliances, has been destroyed or scattered by an army collected within the limits of the Northwestern Provinces and the Punjaub alone.

‘The work has been done before the support of those battalions which have been collected in Bengal from the forces of the Queen in China and in her Majesty’s eastern colonies could reach Major-general Wilson’s army; and it is by the courage and endurance of that gallant army alone, by the skill, sound judgment, and steady resolution of its brave commander, and by the aid of some native chiefs true to their allegiance, that, under the blessing of God, the head of the rebellion has been crushed, and the cause of loyalty, humanity, and rightful authority vindicated.’

83

Chap. vi., pp. 82-96. Chap. x., pp. 163-165. Chap, xv., pp. 247-263.

84

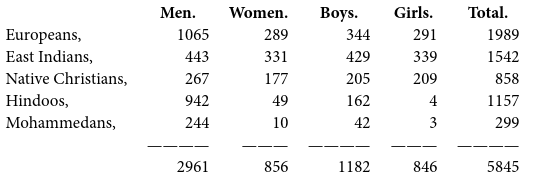

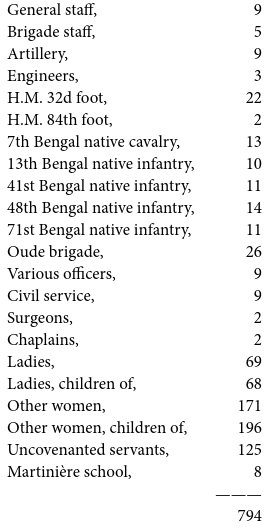

Another account gave the number 865, including about 50 native children in the Martinière school.

85

Personal Narrative of the Siege of Lucknow, from its Commencement to its Relief. By L. E. Ruutz Rees, one or the Survivors.

A Lady’s Diary of the Siege of Lucknow, written for the Perusal of Friends at Home.

A Personal Journal of the Siege of Lucknow. By Captain R. P. Anderson, 25th Regiment N. I., commanding an outpost.

The Defence of Lucknow: a Diary recording the Daily Events during the Siege of the European Residency. By a Staff-officer.

86

In a former chapter (p. 84), a brief notice is given of Claude Martine, a French adventurer who rose to great wealth and influence at Lucknow, and who lived in a fantastic palace called Constantia, southeastward of the city. His name will, however, be more favourably held in remembrance as the founder of a college, named by him the Martinière, for Eurasian or half-caste children. This college was situated near the eastern extremity of the city; but when the troubles began, the principals and the children removed to a building hastily set apart for them within the Residency enclosure. The authoress of the Lady’s Diary, whose husband was connected as a pastor with the Martinière, thus speaks of this transfer: ‘The Martinière is abandoned, and I suppose we shall lose all our remaining property, which we have been obliged to leave to its fate, as nothing more can be brought in here. We got our small remnant of clothes; but furniture, harp, books, carriage-horses, &c., are left at the Martinière. The poor boys are all stowed away in a hot close native building, and it will be a wonder if they don’t get ill.’