полная версия

полная версияThe History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China and Japan 1856-7-8

12

The initials N. I., B. N. I., M. N. I., &c., are frequently used in official documents as abbreviations of ‘Native Infantry,’ ‘Bengal Native Infantry,’ ‘Madras Native Infantry,’ &c.

13

Viscount Canning, in a letter written on the 7th of June to Lieutenant do Kantzow, said: ‘I have read the account of your conduct with an admiration and respect I cannot adequately describe. Young in years, and at the outset of your career, you have given to your brother-soldiers a noble example of courage, patience, good judgment, and temper, from which many may profit. I beg you to believe that it will never be forgotten by me. I write this at once, that there may be no delay in making known to you that your conduct has not been overlooked. You will, of course, receive a more formal acknowledgment, through the military department of the government, of your admirable service.’

14

Irving: Theory and Practice of Caste.

15

Report of Select Committee of House of Commons, 1832.

16

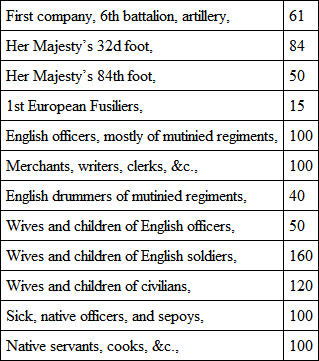

The number of persons in the intrenchment on that day will probably never be accurately known; but Mr Shepherd, from the best materials available to him, made the following estimate:

17

‘Mamma died, July 12.’ ‘Alice died, July 9.’ ‘George died, June 27.’ ‘Entered the barracks, May 21.’ ‘Cavalry left, June 5.’ ‘First shot fired, June 6.’ ‘Uncle Willy died, June 18.’ ‘Aunt Lilly, June 17.’

18

The following is an extract of a letter written by Major Macdonald, after the attack upon him and his brother-officers: ‘Two days after, my native officer said he had found out the murderers, and that they were three men of my own regiment. I had them in irons in a crack, held a drumhead court-martial, convicted, and sentenced them to be hanged the next morning. I took on my own shoulders the responsibility of hanging them first, and asking leave to do so afterwards. That day was an awful one of suspense and anxiety. One of the prisoners was of very high caste and influence, and this man I determined to treat with the greatest ignominy, by getting the lowest caste man to hang him. To tell you the truth, I never for a moment expected to leave the hanging scene alive; but I was determined to do my duty, and well knew the effect that pluck and decision had on the natives. The regiment was drawn out; wounded cruelly as I was, I had to see everything done myself, even to the adjusting of the ropes, and saw them looped to run easy. Two of the culprits were paralysed with fear and astonishment, never dreaming that I should dare to hang them without an order from government. The third said he would not be hanged, and called on the Prophet and on his comrades to rescue him. This was an awful moment; an instant’s hesitation on my part, and probably I should have had a dozen of balls through me; so I seized a pistol, clapped it to the man’s ear, and said, with a look there was no mistake about: “Another word out of your mouth, and your brains shall be scattered on the ground.” He trembled, and held his tongue. The elephant came up, he was put on his back, the rope adjusted, the elephant moved, and he was left dangling. I then had the others up, and off in the same way. And after some time, when I had dismissed the men of the regiment to their lines, and still found my head on my shoulders, I really could scarcely believe it.’

19

Dinapoor is remarkable for the fine barracks built by the Company for the accommodation of troops – for the officers, the European troops, and the native troops; most of the officers have commodious bungalows in the vicinity; and the markets or bazaars, for the supply of Europeans as well as natives, are unusually large and well supplied.

20

‘At present the men of bad character in some regiments, and other people in the direction of Meerut and Delhi, have turned from their allegiance to the bountiful government, and created a seditious disturbance, and have made choice of the ways of ingratitude, and thrown away the character of sepoys true to their salt.

‘At present it is well known that some European regiments have started to punish and coerce these rebels; we trust that by the favour of the bountiful government, we also may be sent to punish the enemies of government, wherever they are; for if we cannot be of use to government at this time, how will it be manifest and known to the state that we are true to our salt? Have we not been entertained in the army for days like the present? In addition to this, government shall see what their faithful sepoys are like, and we will work with heart and soul to do our duty to the state that gives us our salt.

‘Let the enemies of government be who they may, we are ready to fight them, and to sacrifice our lives in the cause.

‘We have said as much as is proper; may the sun of your wealth and prosperity ever shine.

‘The petition of your servants:

Heera Sing, Subadar,

Ellahee Khan, Subadar,

Bhowany Sing, Jemadar,

Munroop Sing, Jemadar,

Heera Sing, Jemadar,

Isseree Pandy, Jemadar,

Murdan Sing, Jemadar,

of the Burra Crawford’s, or 7th regiment, native infantry, and of every non-commissioned officer and sepoy in the lines. Presented on the 3d June 1857.’

21

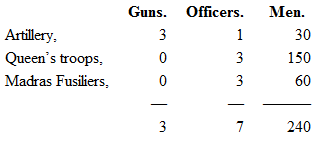

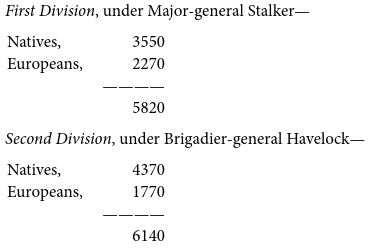

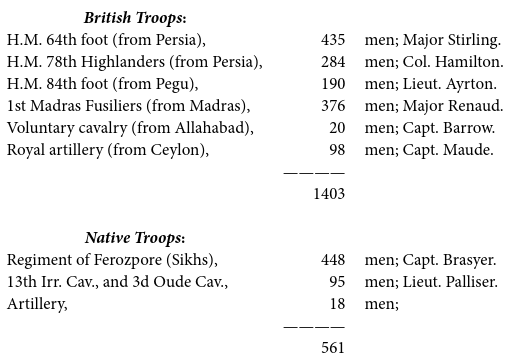

The exact components of this gallant little band appear to have been as follow:

Irrespective of the officers belonging to the mutinous regiments.

Irrespective of the officers belonging to the mutinous regiments.

22

Artillery: 4 guns, horse light field-battery; 6 guns, Oude field-battery; and 1 8-inch howitzer. Cavalry: 120 troopers of 1st, 2d, and 3d Oude irregular cavalry; and 40 volunteer cavalry, under Captain Radcliffe. Infantry: 300 of H.M. 32d foot; 150 of 13th native infantry; 60 of the 48th native infantry; and 20 of the 71st.

23

‘Every boy has read, and many living men still remember, how the death of Nelson was felt by all as a deep personal affliction. Sir Henry Lawrence was less widely known, and his deeds were in truth of less magnitude than those of the great sea-captain; but never probably was a public man within the sphere of his reputation more ardently beloved. Sir Henry Lawrence had that rare and happy faculty (which a man in almost every other respect unlike him, Sir Charles Napier, is said also to have possessed) of attaching to himself every one with whom he came in contact. He had that gift which is never acquired, a gracious, winning, noble manner; rough and ready as he was in the field, his manner in private life had an indescribable charm of frankness, grace, and even courtly dignity. He had that virtue which Englishmen instinctively and characteristically love – a lion-like courage. He had that fault which Englishmen so readily forgive, and when mixed with what are felt to be its naturally concomitant good qualities, they almost admire – a hot and impetuous temper; he had in overflowing measure that Godlike grace which even the base revere and the good acknowledge as the crown of virtue – the grace of charity. No young officer ever sat at Sir Henry’s table without learning to think more kindly of the natives; no one, young or old, man or woman, ever heard Sir Henry speak of the European soldier, or ever visited the Lawrence Asylum, without being excited to a nobler and truer appreciation of the real extent of his duty towards his neighbour. He was one of the few distinguished Anglo-Indians who had attained to something like an English reputation in his lifetime. In a few years, his name will be familiar to every reader of Indian history; but for the present it is in India that his memory will be most deeply cherished; it is by Anglo-Indians that any eulogy on him will be best appreciated, it is by them that the institutions which he founded and maintained will be fostered as a monument to his memory.’ —Fraser’s Magazine, No. 336.

24

The troops stationed at that time at Fyzabad comprised the 22d regiment native infantry; the 6th regiment irregular Oude infantry; the 5th troop of the 15th regiment irregular cavalry; No. 5 company of the 7th battalion of artillery; and No. 13 horse-battery. The chief officers were Colonels Lennox and O’Brien; Major Mill; Captain Morgan; Lieutenants Fowle, English, Bright, Lindesay, Thomas, Ouseley, Cautley, Gordon, Parsons, Percival, and Currie; and Ensigns Anderson and Ritchie. Colonel Goldney held a civil appointment as commissioner.

25

A curious example was afforded, in relation to the affairs of Saugor, of the circuitous manner in which public affairs were conducted in India, when different officials were residing in different parts of that vast empire. The brigadier commanding the Saugor district adopted a certain course, in a time of peril, concerning the management of the troops under his command. He sent information of these proceedings to Neill at Allahabad (300 miles). Neill forwarded the information to Calcutta (500 miles). The military secretary to the government at Calcutta sent a dispatch to the adjutant-general of the army outside Delhi (900 miles), requesting him to ‘move’ the commander-in-chief to send a military message to Saugor (400 miles), calling upon the officer of that station to explain the motives for his conduct in the matter at issue. The explanation, so given, was to be sent 400 miles to Delhi, and then 900 miles to Calcutta; and lastly, if the conduct were not approved, a message to that effect would be sent, by any route that happened to be open for dâk, from Calcutta to Saugor.

26

‘To mark the approbation with which he has received this report, the Right Honourable the Governor in Council will direct the immediate promotion to higher grades of such of the native officers and men as his Excellency the Commander-in-chief may be pleased to name as having most distinguished themselves on this occasion, and thereby earned this special reward; and the Governor will take care that liberal compensation is awarded for the loss of property abandoned in the cantonment and subsequently destroyed, when the Lancers, in obedience to orders, marched out to protect the families of the European officers, leaving their own unguarded in cantonment.

‘By a later report the Governor in Council has learned with regret that eleven men of the Lancers basely deserted their comrades and their standards, and joined the mutineers; but the Governor in Council will not suffer the disgrace of these unworthy members of the corps to sully the display of loyalty, discipline, and gallantry which the conduct of this fine regiment has eminently exhibited.’

27

It is well to observe, for the aid of those consulting maps, that there are five or six towns and villages of this name in India. The Mhow here indicated is nearly in lat. 22½°, long. 76°.

28

See page 175.

29

The events of the mutiny relating to the Punjaub have been ably set forth in a series of papers in Blackwood’s Magazine, written by an officer on the spot.

30

This column was made up as follows:

1. H.M. 27th foot, from Nowsherah.

2. H.M. 24th foot, from Rawul Pindee.

3. One troop European horse-artillery, from Peshawur.

4. One light field-battery, from Jelum.

5. The Guide Corps, from Murdan.

6. The 16th irregular cavalry, from Rawul Pindee.

7. The 1st Punjaub infantry, from Bunnoo.

8. The Kumaon battalion, from Rawul Pindee.

9. A wing of the 2d Punjaub cavalry, from Kohat.

10. A half company of Sappers, from Attock.

31

‘Very Dear and Good Mother – On the 8th of the present month the native soldiers heard they were to be disarmed the following day. They became furious, and secretly planned a revolt. They carried their plans into execution at an early hour on the following morning. We were immediately apprised of it, and I hastened to awake our poor children, and all of us, half-clad, prayed for shelter at a Hindoo habitation. Some vehicles had been prepared for us to escape, when the servants desired us to conceal ourselves, as the sepoys were coming into the garden. We returned to our hiding-place; the soldiers arrived; they took away our carriages, and a shot was fired into the house where we were concealed. The ball passed close to where our chaplain was sitting, and slightly wounded a child in the leg. At the same moment three soldiers, well armed, presented themselves at the door. The good father, holding the holy sacrament, which he never quitted, advanced to meet them. Several of us accompanied him. “We have orders to kill you,” said the sepoys; “but we will spare you if you give us money. Go out, all, that we may see there are no men concealed here.” Having searched and found nothing, one of the soldiers raised his sabre over the chaplain, and cried out: “You shall die.” “Mercy, in the name of God!” exclaimed I. “I will open every press to shew you that there is no money concealed here.” He followed me, and having satisfied himself that there was no money, the soldiers went away. We then broke a hole in the wall of our garden, and fled into the jungle. We had scarcely escaped when thirty more sepoys entered the house; but the Almighty preserved us from this danger. We were crossing the country, when a faithful servant brought us to a house where several Europeans had taken refuge. We breathed freely there for a moment, but the government treasure was deposited there, and the house was soon attacked by the mutinous sepoys. We believed that our last hour was at hand; but the savages were too much occupied with pillage to notice us, and the Europeans escaped. At this moment a Catholic soldier offered to guide us to the fort, where we arrived at twelve o’clock. We do not know how long we shall remain in the fort. The English officers have treated us with the greatest kindness and attention, and have supplied us with provisions both for ourselves and our pupils. We trust we shall one day make our way to Bombay; but that will depend on the orders we receive from the government.’

32

The brigadier’s confidence in his men was conditional on their implicit obedience; and he was wont to affirm that his ‘Irregulars’ were as ‘regular’ in conduct and discipline as the Queen’s Life-guards themselves. He would allow no religious scruples to interfere with their military efficiency. On one occasion, during the Mohurram or Mohammedan religious festival in 1854, there was great uproar and noise among ten thousand Mussulmans assembled in and near his camp of Jacobabad to celebrate their religious festival. He issued a general order: ‘The commanding officer has nothing to do with religious ceremonies. All men may worship God as they please, and may act and believe as they choose, in matters of religion; but no men have a right to annoy their neighbours, or to neglect their duty, on pretence of serving God. The officers and men of the Sinde Horse have the name of, and are supposed to be, excellent soldiers, and not mad fakeers… He therefore now informs the Sinde Irregular Horse, that in future no noisy processions, nor any disorderly display whatever, under pretence of religion or anything else, shall ever be allowed in, or in neighbourhood of, any camp of the Sinde Irregular Horse.’

33

34

35

36

In August 1857, of the whole railway distance marked out from Alexandria through Cairo to Suez, 205 miles in length, about 175 miles were finished – namely, from Alexandria to the crossing of the Nile, 65 miles; from the crossing of the Nile to Cairo, 65 miles; from Cairo towards Suez, 45 miles. The remainder of the journey consisted of 30 miles of sandy desert, not at that time provided with a railway, but traversed by omnibuses or vans.

37

‘According to existing regulations of some years’ standing, every soldier on his arrival in India is provided with the following articles of clothing, in addition to those which compose his kit in this country:

‘Mounted Men. – 4 white jackets, 6 pair of white overalls, 2 pair of Settringee overalls, 6 shirts, 4 pair of cotton socks, 1 pair of white braces.

‘Foot-soldiers. – 4 white jackets, 1 pair of English summer trousers, 5 pair of white trousers, 5 white shirts, 2 check shirts, 1 pair of white braces.

‘These articles are not supplied in this country, but form a part of the soldier’s necessaries on his arrival in India, and are composed of materials made on the spot, and best suited to the climate.

‘During his stay in India, China, Ceylon, and at other hot stations, he is provided with a tunic and shell-jacket in alternate years; and in the year in which the tunic is not issued, the difference in the value of the two articles is paid to the soldier, to be expended (by the officer commanding) for his benefit in any articles suited to the climate of the station.

‘The force recently sent out to China and India has been provided with white cotton helmet and forage-cap covers.

‘Any quantity of light clothing for troops can be procured on the spot in India at the shortest notice.’

38

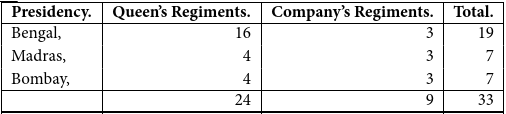

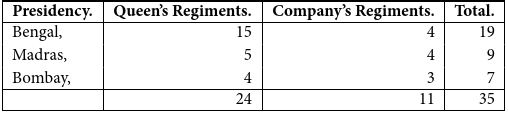

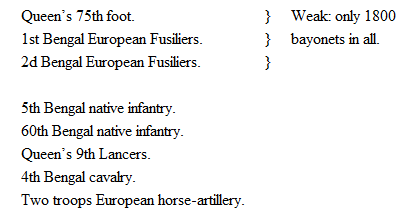

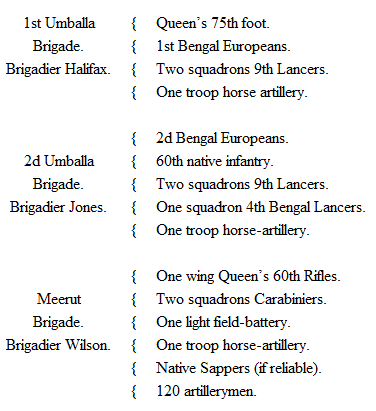

The troops at Umballa on the 17th comprised:

39

40

Four guns of Major Tombs’ horse-artillery.

Major Scott’s horse field-battery.

Two 18-pounders, under Lieutenant Light.

Two squadrons of Carabiniers.

Six companies of 60th Rifles.

400 Sirmoor Goorkhas.

41

Head-quarters and six companies of H.M. 60th Rifles.

Head-quarters and nine companies of H.M. 75th foot.

1st Bengal European Fusiliers.

2d Bengal European Fusiliers head-qurs. and six companies.

Sirmoor battalion (Goorkhas), a wing.

Head-quarters detachment Sappers and Miners.

H.M. 9th Lancers.

H.M. 6th Dragoon-guards (Carabiniers), two squadrons.

Horse-artillery, one troop of 1st brigade.

Horse-artillery, two troops of 3d brigade.

Foot-artillery, two companies, and No. 14 horse-battery.

Artillery recruits, detachment.

42

Chapter iv., pp. 63-65.

43

After the execution of Mungal Pandy at Barrackpore on the 8th of April, for mutiny, the rebel sepoys acquired the soubriquet of ‘Pandies’ – especially those belonging to the Brahmin caste.

44

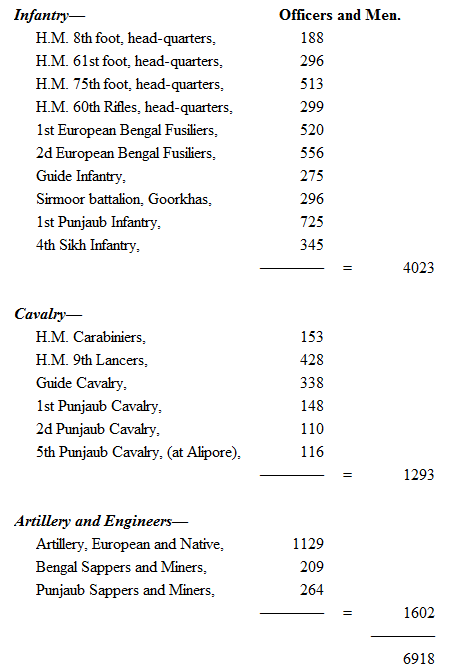

Besides these effectives, there were as non-effectives, 765 sick + 351 wounded = 1116.

45

Bengal native infantry: 3d, 9th, 11th, 12th, 15th, 20th, 28th, 29th, 30th, 36th, 38th, 44th, 45th, 54th, 57th, 60th, 61st, 67th, 68th, 72d, 74th, 78th.

Other native infantry: 5th and 7th Gwalior Contingent, Kotah Contingent, Hurrianah battalion; together with 2600 miscellaneous infantry.

Native cavalry: Portions of five or six regiments, besides others of the Gwalior and Malwah Contingents.

46

It may be useful to note, for readers unfamiliar with military matters, the meaning of the words brevet and brigadier. A brevet is a commission, conferring on an officer a degree of rank next above that which he holds in his particular regiment; without, however, conveying the power of receiving the corresponding pay. Besides being honorary as a mark of distinction, it qualifies the officer to succeed to the full possession of the higher rank on a vacancy occurring, in preference to one not holding a brevet. In the British army brevet rank only applies to captains, majors, and lieutenant-colonels. A brigadier is a colonel or other officer of a regiment who is made temporarily a general officer for a special service, in command of a brigade, or more than one regiment. It is not a permanent rank, but is considered as a stepping-stone to the office of major-general. Many Indian officers who were colonels when the Indian mutiny began, such as Henry Lawrence and Neill, were appointed brigadier-generals for a special service, and rose to higher rank before the mutiny was ended.

47

Chapter ix., pp. 159-161.

48

Colonel Tytler and Captain Beatson officiated as quarter-master-general and adjutant-general of the force, irrespective of particular regiments.

49

‘Brigadier-general Havelock thanks his soldiers for their arduous exertion of yesterday, which produced, in four hours, the strange result of a whole army driven from a strong position, eleven guns captured, and their whole force scattered to the winds, without the loss of a single British soldier!

‘To what is this astonishing effect to be attributed? To the fire of the British artillery, exceeding in rapidity and precision all that the brigadier-general has ever witnessed in his not short career; to the power of the Enfield rifle in British hands; to British pluck, that good quality that has survived the revolution of the hour; and to the blessing of Almighty God on a most righteous cause – the cause of justice, humanity, truth, and good government in India.’

50

‘The important duty of first relieving the garrison of Lucknow has been intrusted to Major-general Havelock, C.B.; and Major-general Outram feels that it is due to this distinguished officer, and to the strenuous and noble exertions which he has already made to effect that object, that to him should accrue the honour of the achievement.

‘Major-general Outram is confident that the great end for which General Havelock and his brave troops have so long and so gloriously fought will now, under the blessing of Providence, be accomplished.

‘The major-general, therefore, in gratitude for and admiration of the brilliant deeds in arms achieved by General Havelock and his gallant troops, will cheerfully waive his rank on the occasion, and will accompany the force to Lucknow in his civil capacity as chief-commissioner of Oude, tendering his military services to General Havelock as a volunteer.

‘On the relief of Lucknow, the major-general will resume his position at the head of the forces.’

51

‘FIRST INFANTRY BRIGADE‘The 5th Fusiliers; 84th regiment; detachments 64th foot and 1st Madras Fusiliers: – Brigadier-general Neill commanding, and nominating his own brigade staff.

‘SECOND INFANTRY BRIGADE‘Her Majesty’s 78th Highlanders; her Majesty’s 90th Light Infantry; and the Sikh regiment of Ferozpore: – Brigadier Hamilton commanding, and nominating his own brigade staff.

‘THIRD (ARTILLERY) BRIGADE‘Captain Maude’s battery; Captain Olphert’s battery; Brevet-Major Eyre’s battery: – Major Cope to command, and to appoint his own staff.