полная версия

полная версияHeroes of Science: Physicists

On September 1, 1730, Franklin married his former fiancée, whose previous husband had left her and was reported to have died in the West Indies. The marriage was a very happy one, and continued over forty years, Mrs. Franklin living until the end of 1774. Industry and frugality reigned in the household of the young printer. Mrs. Franklin not only managed the house, but assisted in the business, folding and stitching pamphlets, and in other ways making herself useful. The first part of Franklin's autobiography concludes with an account of the foundation of the first subscription library. By the co-operation of the members of the Junto, fifty subscribers were obtained, who each paid in the first instance forty shillings, and afterwards ten shillings per annum. "We afterwards obtained a charter, the company being increased to one hundred. This was the mother of all the North American subscription libraries, now so numerous. It is become a great thing itself, and continually increasing. These libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans, made the common tradesmen and farmers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the stand so generally made throughout the colonies in defence of their privileges."

Ten years ago this library contained between seventy and eighty thousand volumes.

Franklin's success in business was attributed by him largely to his early training. "My circumstances, however, grew daily easier. My original habits of frugality continuing, and my father having, among his instructions to me when a boy, frequently repeated a proverb of Solomon, 'Seest thou a man diligent in his business? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before mean men,' I from thence considered industry as a means of obtaining wealth and distinction, which encourag'd me, tho' I did not think that I should ever literally stand before kings, which, however, has since happened; for I have stood before five, and even had the honour of sitting down with one, the King of Denmark, to dinner."

After his marriage, Franklin conceived the idea of obtaining moral perfection. He was not altogether satisfied with the result, but thought his method worthy of imitation. Assuming that he possessed complete knowledge of what was right or wrong, he saw no reason why he should not always act in accordance therewith. His principle was to devote his attention to one virtue only at first for a week, at the end of which time he expected the practice of that virtue to have become a habit. He then added another virtue to his list, and devoted his attention to the same for the next week, and so on, until he had exhausted his list of virtues. He then commenced again at the beginning. As his moral code comprised thirteen virtues, it was possible to go through the complete curriculum four times in a year. Afterwards he occupied a year in going once through the list, and subsequently employed several years in one course. A little book was ruled, with a column for each day and a line for each virtue, and in this a mark was made for every failure which could be remembered on examination at the end of the day. It is easy to believe his statement: "I am surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish."

"This my little book had for its motto these lines from Addison's 'Cato': —

"'Here will I hold. If there's a Power above us(And that there is, all Nature cries aloudThro' all her work), He must delight in virtue;And that which He delights in must be happy.'"Another from Cicero: —

"'O vitæ Philosophia dux! O virtutum indagatrix expultrixque vitiorum! Unus dies ex præceptis tuis actus, peccanti immortalitati est anteponendus.'

"Another from the Proverbs of Solomon, speaking of wisdom and virtue: —

"'Length of days is in her right hand; and in her left hand riches and honour. Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace.'

"And conceiving God to be the fountain of wisdom, I thought it right and necessary to solicit His assistance for obtaining it; to this end I formed the following little prayer, which was prefixed to my tables of examination, for daily use: —

"'O powerful Goodness! bountiful Father! merciful Guide! increase in me that wisdom which discovers my truest interest. Strengthen my resolutions to perform what that wisdom dictates. Accept my kind offices to Thy other children as the only return in my power for Thy continual favours to me.'

"I used also sometimes a little prayer which I took from Thomson's Poems, viz.: —

"'Father of light and life, Thou Good Supreme!Oh teach me what is good; teach me Thyself!Save me from folly, vanity, and vice,From every low pursuit; and fill my soulWith knowledge, conscious peace, and virtue pure;Sacred, substantial, never-failing bliss!'"The senses in which Franklin's thirteen virtues were to be understood were explained by short precepts which followed them in his list. The list was as follows: —

"1. Temperance"Eat not to dulness; drink not to elevation.

"2. Silence"Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

"3. Order"Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

"4. Resolution"Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

"5. Frugality"Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i. e. waste nothing.

"6. Industry"Lose no time; be always employed in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

"7. Sincerity"Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly; and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

"8. Justice"Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

"9. Moderation"Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

"10. Cleanliness"Tolerate no uncleanness in body, clothes, or habitation.

"11. Tranquillity"Be not disturbed at trifles, or accidents common or unavoidable.

"12. Chastity"13. Humility"Imitate Jesus and Socrates."

The last of these was added to the list at the suggestion of a Quaker friend. Franklin claims to have acquired a good deal of the appearance of it, but concluded that in reality there was no passion so hard to subdue as pride. "For even if I could conceive that I had completely overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility." The virtue which gave him most trouble, however, was order, and this he never acquired.

In 1732 appeared the first copy of "Poor Richard's Almanack." This was prepared, printed, and published by Franklin for about twenty-five years in succession, and nearly ten thousand copies were sold annually. Besides the usual astronomical information, it contained a collection of entertaining anecdotes, verses, jests, etc., while the "little spaces that occurred between the remarkable events in the calendar" were filled with proverbial sayings, inculcating industry and frugality as helps to virtue. These sayings were collected and prefixed to the almanack of 1757, whence they were copied into the American newspapers, and afterwards reprinted as a broad-sheet in England and in France.

In 1733 Franklin commenced studying modern languages, and acquired sufficient knowledge of French, Italian, and Spanish to be able to read books in those languages. In 1736 he was chosen Clerk to the General Assembly, an office to which he was annually re-elected until he became a member of the Assembly about 1750. There was one member who, on the second occasion of his election, made a long speech against him. Franklin determined to secure the friendship of this member. Accordingly he wrote to him to request the loan of a very scarce and curious book which was in his library. The book was lent and returned in about a week, with a note of thanks. The member ever after manifested a readiness to serve Franklin, and they became great friends – "Another instance of the truth of an old maxim I had learned, which says, 'He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another than he whom you yourself have obliged.' And it shows how much more profitable it is prudently to remove, than to resent, return, and continue inimical proceedings."

In 1737 Franklin was appointed Deputy-Postmaster-General for Pennsylvania. He was afterwards made Postmaster-General of the Colonies. He read a paper in the Junto on the organization of the City watch, and the propriety of rating the inhabitants on the value of their premises in order to support the same. The subject was also discussed in the other clubs which had sprung from the Junto, and thus the way was prepared for the law which a few years afterwards carried Franklin's proposals into effect. His next scheme was the formation of a fire brigade, in which he met with his usual success, and other clubs followed, until most of the men of property in the city were members of one club or another. The original brigade, known as the Union Fire Company, was formed December 7, 1736. It was in active service in 1791.

Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society in 1743. The head-quarters of the society were fixed in Philadelphia, where it was arranged that there should always be at least seven members, viz. a physician, a botanist, a mathematician, a chemist, a mechanician, a geographer, and a general natural philosopher, besides a president, treasurer, and secretary. The other members might be resident in any part of America. Correspondence was to be kept up with the Royal Society of London and the Dublin Society, and abstracts of the communications were to be sent quarterly to all the members. Franklin became the first secretary.

Spain, having been for some years at war with England, was joined at length by France. This threatened danger to the American colonies, as France then held Canada, and no organization for their defence existed. Franklin published a pamphlet entitled "Plain Truth," setting forth the unarmed condition of the colonies, and recommending the formation of a volunteer force for defensive purposes. The pamphlet excited much attention. A public meeting was held and addressed by Franklin; at this meeting twelve hundred joined the association. At length the number of members enrolled exceeded ten thousand. These all provided themselves with arms, formed regiments and companies, elected their own officers, and attended once a week for military drill. Franklin was elected colonel of the Philadelphia Regiment, but declined the appointment, and served as a private soldier. The provision of war material was a difficulty with the Assembly, which consisted largely of Quakers, who, though they appeared privately to be willing that the country should be put in a state of defence, hesitated to vote in opposition to their peace principles. Hence it was that, when the Government of New England asked a grant of gunpowder from Pennsylvania, the Assembly voted £3000 "for the purchasing of bread, flour, wheat, or other grain." Pebble-powder was not then in use. When it was proposed to devote £60, which was a balance in the hands of the Union Fire Company, as a contribution towards the erection of a battery below the town, Franklin suggested that it should be proposed that a fire-engine be purchased with the money, and that the committee should "buy a great gun, which is certainly a fire-engine."

The "Pennsylvania fireplace" was invented in 1742. A patent was offered to Franklin by the Governor of Pennsylvania, but he declined it on the principle "that, as we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously." An ironmonger in London made slight alterations, which were not improvements, in the design, and took out a patent for the fireplace, whereby he made a "small fortune." Franklin never contested the patent, "having no desire of profiting by patents himself," and "hating disputes." This fireplace was designed to burn wood, but, unlike the German stoves, it was completely open in front, though enclosed at the sides and top. An air-chamber was formed in the middle of the stove, so arranged that, while the burning wood was in contact with the front of the chamber, the flame passed above and behind it on its way to the flue. Through this chamber a constant current of air passed, entering the room heated, but not contaminated, by the products of combustion. In this way the stove furnished a constant supply of fresh warm air to the room, while it possessed all the advantages of an open fireplace. Subsequently Franklin contrived a special fireplace for the combustion of coal. In the scientific thought which he devoted to the requirements of the domestic economist, as in very many other particulars, Franklin strongly reminds us of Count Rumford.

The next important enterprise which Franklin undertook, partly through the medium of the Junto, was to establish an academy which soon developed into the University of Philadelphia. The members of the club having taken up the subject, the next step was to enlist the sympathy of a wider constituency, and this Franklin effected, in his usual way, by the publication of a pamphlet. He then set on foot a subscription, the payments to extend over five years, and thereby obtained about £5000. A house was taken and schools opened in 1749. The classes soon became too large for the house, and the trustees of the academy then took over a large building, or "tabernacle," which had been erected for George Whitefield when he was preaching in Philadelphia. The hall was divided into stories, and at a very small expense adapted to the requirements of the classes. Franklin, having taken a partner in his printing business, took the oversight of the work. Afterwards the funds were increased by English subscriptions, by a grant from the Assembly, and by gifts of land from the proprietaries; and thus was established the University of Philadelphia.

Having practically retired from business, Franklin intended to devote himself to philosophical studies, having commenced his electrical researches some time before in conjunction with the other members of the Library Company. Public business, however, crowded upon him. He was elected a member of the Assembly, a councillor and afterwards an alderman of the city, and by the governor was made a justice of the peace. As a member of the Assembly, he was largely concerned in providing the means for the erection of a hospital, and in arranging for the paving and cleansing of the streets of the city. In 1753 he was appointed, in conjunction with Mr. Hunter, Postmaster-General of America. The post-office of the colonies had previously been conducted at a loss. In a few years, under Franklin's management, it not only paid the stipends of himself and Mr. Hunter, but yielded a considerable revenue to the Crown. But it was not only in the conduct of public business that Franklin's merits were recognized. By this time he had secured his reputation as an electrician, and both Yale College and Cambridge University (New England) conferred on him the honorary degree of Master of Arts. In the same year that he was made Postmaster-General of America he was awarded the Copley Medal and elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, the usual fees being remitted in his case.

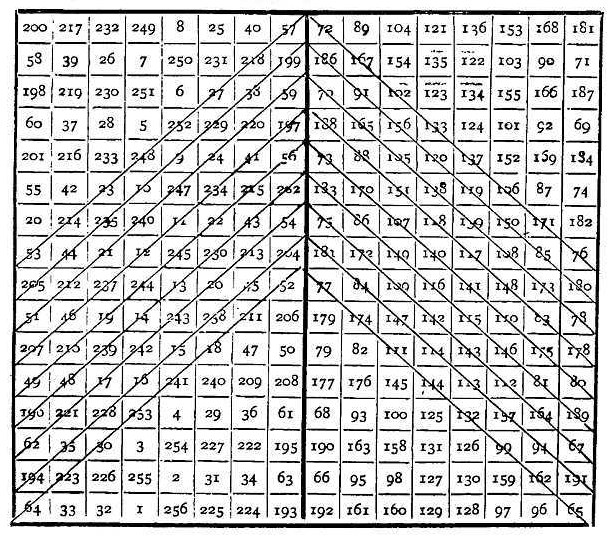

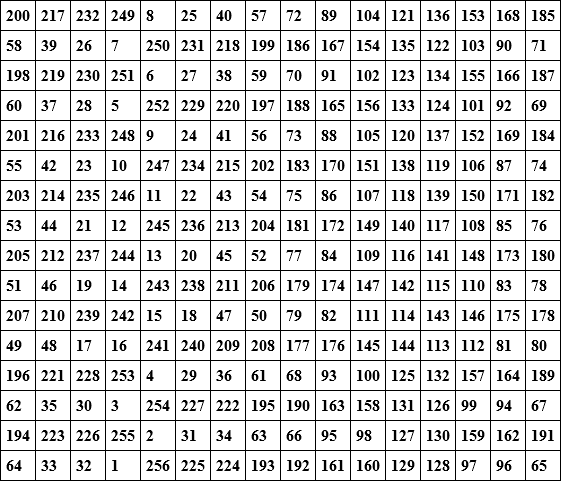

Before his election as member, Franklin had for several years held the appointment of Clerk to the Assembly, and he used to relieve the dulness of the debates by amusing himself in the construction of magic circles and squares, and "acquired such a knack at it" that he could "fill the cells of any magic square of reasonable size with a series of numbers as fast as" he "could write them." Many years afterwards Mr. Logan showed Franklin a French folio volume filled with magic squares, and afterwards a magic "square of 16," which Mr. Logan thought must have been a work of great labour, though it possessed only the common properties of making 2056 in every row, horizontal, vertical, and diagonal. During the evening Franklin made the square shown on the opposite page. "This I sent to our friend the next morning, who, after some days, sent it back in a letter, with these words: 'I return to thee thy astonishing and most stupendous piece of the magical square, in which – ;' but the compliment is too extravagant, and therefore, for his sake as well as my own, I ought not to repeat it. Nor is it necessary; for I make no question that you will readily allow this square of 16 to be the most magically magical of any magic square ever made by any magician."

The square has the following properties: – Every straight row of sixteen numbers, whether vertical, horizontal, or diagonal, makes 2056.

Every bent row of sixteen numbers, as shown by the diagonal lines in the figure, makes 2056.

If a square hole be cut in a piece of paper, so as to show through it just sixteen of the little squares, and the paper be laid on the magic square, then, wherever the paper is placed, the sum of the sixteen numbers visible through the hole will be 2056.

In 1754 war with France appeared to be again imminent, and a Congress of Commissioners from the several colonies was arranged for. Of course, Franklin was one of the representatives of Pennsylvania, and was also one of the members who independently drew up a plan for the union of all the colonies under one government, for defensive and other general purposes, and his was the plan finally approved by Congress for the union, though it was not accepted by the Assemblies or by the English Government, being regarded by the former as having too much of the prerogative in it, by the latter as being too democratic. Franklin wrote respecting this scheme: "The different and contrary reasons of dislike to my plan makes me suspect that it was really the true medium; and I am still of opinion that it would have been happy for both sides of the water if it had been adopted. The colonies, so united, would have been sufficiently strong to have defended themselves; there would then have been no need of troops from England; of course, the subsequent pretence for taxing America, and the bloody contest it occasioned, would have been avoided."

With this war against France began the struggle of the Assemblies and the proprietaries on the question of taxing the estates of the latter. The governors received strict instructions to approve no bills for the raising of money for the purposes of defence, unless the estates of the proprietaries were specially exempted from the tax. The Assembly of Pennsylvania resolved to contribute £10,000 to assist the Government of Massachusetts Bay in an attack upon Crown Point, but the governor refused his assent to the bill for raising the money. At this juncture Franklin proposed a scheme by which the money could be raised without the consent of the governor. His plan was successful, and the difficulty was surmounted for the time, but was destined to recur again and again during the progress of the war.

The British Government, not approving of the scheme of union, whereby the colonies might have defended themselves, sent General Braddock to Virginia, with two regiments of regular troops. On their arrival they found it impossible to obtain waggons for the conveyance of their baggage, and the general commissioned Franklin to provide them in Pennsylvania. By giving his private bond for their safety, Franklin succeeded in engaging one hundred and fifty four-horse waggons, and two hundred and fifty-nine pack-horses. His modest warnings against Indian ambuscades were disregarded by the general, the little army was cut to pieces, and the remainder took to flight, sacrificing the whole of their baggage and stores. Franklin was never fully recouped by the British Government for the payments he had to make on account of provisions which the general had instructed him to procure for the use of the army.

After this, Franklin appeared for some time in a purely military capacity, having yielded to the governor's persuasions to undertake the defence of the north-western frontier, to raise troops, and to build a line of forts. After building and manning three wooden forts, he was recalled by the Assembly, whose relations with the governor had become more and more strained. At length the Assembly determined to send Franklin to England, to present a petition to the king respecting the conduct of the proprietaries, viz. Richard and Thomas Penn, the successors of William Penn. A bill had been framed by the House to provide £60,000 for the king's use in the defence of the province. This the governor refused to pass, because the proprietary estates were not exempted from the taxation. The petition to the king was drawn up, and Franklin's baggage was on board the ship which was to convey him to England, when General Lord Loudon endeavoured to make an arrangement between the parties. The governor pleaded his instructions, and the bond he had given for carrying them out, and the Assembly was prevailed upon to reconstruct the bill in accordance with the governor's wishes. This was done under protest; in the mean time Franklin's ship had sailed, carrying his baggage. After a great deal of unnecessary delay on account of the general's inability to decide upon the despatch of the packet-boats, Franklin at last got away from New York, and, having narrowly escaped shipwreck off Falmouth, he reached London on July 27, 1757.

On arriving in London, Franklin was introduced to Lord Granville, who told him that the king's instructions were laws in the colonies. Franklin replied that he had always understood that the Assemblies made the laws, which then only required the king's consent. "I recollected that, about twenty years before, a clause in a bill brought into Parliament by the Ministry had proposed to make the king's instructions laws in the colonies, but the clause was thrown out by the Commons, for which we adored them as our friends and the friends of liberty, till, by their conduct towards us in 1765, it seem'd that they had refus'd that point of sovereignty to the king only that they might reserve it for themselves." A meeting was shortly afterwards arranged between Franklin and the proprietaries at Mr. T. Penn's house; but their views were so discordant that, after some discussion, Franklin was requested to give them in writing the heads of his complaints, and the whole question was submitted to the opinion of the attorney- and solicitor-general. It was nearly a year before this opinion was given. The proprietaries then communicated directly with the Assembly, but in the mean while Governor Denny had consented to a bill for raising £100,000 for the king's use, in which it was provided that the proprietary estates should be taxed with the others. When this bill reached England, the proprietaries determined to oppose its receiving the royal assent. Franklin engaged counsel on behalf of the Assembly, and on his undertaking that the assessment should be fairly made between the estates of the proprietaries and others, the bill was allowed to pass.

By this time Franklin's career as a scientific investigator was practically at an end. Political business almost completely occupied his attention, and in one sense the diplomatist replaced the philosopher. His public scientific career was of short duration. It may be said to have begun in 1746, when Mr. Peter Collinson presented an "electrical tube" to the Library Company in Philadelphia, which was some time after followed by a present of a complete set of electrical apparatus from the proprietaries, but by 1755 Franklin's time was so much taken up by public business that there was very little opportunity for experimental work. Throughout his life he frequently expressed in his letters his strong desire to return to philosophy, but the opportunity never came, and when, at the age of eighty-two, he was liberated from public duty, his strength was insufficient to enable him to complete even his autobiography.

It was on a visit to Boston in 1746 that Franklin met with Dr. Spence, a Scotchman, who exhibited some electrical experiments. Soon after his return to Philadelphia the tube arrived from Mr. Collinson, and Franklin acquired considerable dexterity in its use. His house was continually full of visitors, who came to see the experiments, and, to relieve the pressure upon his time, he had a number of similar tubes blown at the glass-house, and these he distributed to his friends, so that there were soon a number of "performers" in Philadelphia. One of these was Mr. Kinnersley, who, having no other employment, was induced by Franklin to become an itinerant lecturer. Franklin drew up a scheme for the lectures, and Kinnersley obtained several well-constructed instruments from Franklin's rough and home-made models. Kinnersley and Franklin appear to have worked together a good deal, and when Kinnersley was travelling on his lecture tour, each communicated to the other the results of his experiments. Franklin sent his papers to Mr. Collinson, who presented them to the Royal Society, but they were not at first judged worthy of a place in the "Transactions." The paper on the identity of lightning and electricity was sent to Dr. Mitchell, who read it before the Royal Society, when it "was laughed at by the connoisseurs." The papers were subsequently published in a pamphlet, but did not at first receive much attention in England. On the recommendation of Count de Buffon, they were translated into French. The Abbé Nollet, who had previously published a theory of his own respecting electricity, wrote and published a volume of letters defending his theory, and denying the accuracy of some of Franklin's experimental results. To these letters Franklin made no reply, but they were answered by M. le Roy. M. de Lor undertook to repeat in Paris all Franklin's experiments, and they were performed before the king and court. Not content with the experiments which Franklin had actually performed, he tried those which had been only suggested, and so was the first to obtain electricity from the clouds by means of the pointed rod. This experiment produced a great sensation everywhere, and was afterwards repeated by Franklin at Philadelphia. Franklin's papers were translated into Italian, German, and Latin; his theory met with all but universal acceptance, and great surprise was expressed that his papers had excited so little interest in England. Dr. Watson then drew up a summary of all Franklin's papers, and this was published in the "Philosophical Transactions;" Mr. Canton verified the experiment of procuring electricity from the clouds by means of a pointed rod, and the Royal Society awarded to Franklin the Copley Medal for 1753, which was conveyed to him by Governor Denny.