Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

A new world was possible because ‘we are witnessing the end of an idea: the final chapter of the communist experiment. Communism is now recognised … as a failed system … But the eclipse of communism is only one half of the story of our time. The other is the ascendancy of the democratic idea’ – evident across the world from trade unionists in Warsaw to students in Beijing. ‘Even as we speak today,’ he told the young American graduands, ‘the world is transfixed by the dramatic events in Tiananmen Square. Everywhere, those voices are speaking the language of democracy and freedom.’[92]

The Coast Guard speech completed Bush’s public exposition of his administration’s new strategy toward the European cockpit of East–West relations ahead of the NATO summit in Brussels on 30 May.[93] His visionary statements about peace and freedom, about global free markets and a community of democracies, give the lie to later claims that his foreign policy was aimless, merely reactive and ‘too unwilling to move in untested waters’. Above all, he was repeatedly emphasising the place of US leadership in the world and asserting what the administration regularly referred to as the ‘common values of the West’.[94] As Bush had said in that scene-setting cameo on Governors Island, he intended to take his time and act prudently in an era when the fundamentals of international relations had been shaken as never before since 1945. ‘Prudence’ would indeed remain a watchword of Bush’s diplomacy but this did not preclude vision and hope. Those speeches of April and May 1989 – often neglected by commentators amid the dramas of the second half of the year – make the ambition of his foreign policy abundantly clear.

But converting ambition into achievement was a different challenge. And his first test was particularly demanding. The NATO summit in Brussels was unusually high profile because it coincided with the fortieth anniversary of the Atlantic Alliance and because it was imperative to come up with an eye-catching response to the potpourri of dramatic arms-reduction proposals Gorbachev had tossed out in his UN speech. To make matters worse, NATO governments had been unable to agree in advance on a joint position, mainly because of fundamental disputes about short-range nuclear forces (SNFs) – those with a range of less than 500 kilometres. And, at a less visible level, the arguments surrounding the NATO summit may be seen as marking a subtle but significant shift in America’s alliance priorities in Western Europe – away from Great Britain and towards West Germany.[95]

Britain, represented by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher – the notorious ‘Iron Lady’ – demanded rapid implementation of a 1985 NATO agreement to modernise its SNFs (eighty-eight Lance missile launchers and some 700 warheads). Her fixation was with their deterrent value and NATO’s defensibility. The coalition government of West Germany, where most of these missiles were stationed, instead pressed the USA to pursue negotiations on SNF reduction with the Soviet Union, building on the success of the superpower 1987 treaty to eliminate all their intermediate nuclear forces (INFs) worldwide. Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher – leader of the junior coalition partner the Free Democrats (FDP) – even lobbied, like Gorbachev, for the total abolition of SNFs. This was known as the ‘third zero’ – building on the ‘double zero’ agreement for the abolition of INFs in Europe and Asia. For Thatcher, relatively secure in her island kingdom, these weapons were an instrument of military strategy but for Genscher and for the German left they were a matter of life or death, because Germany would be the inevitable epicentre of a European war. Kohl considered Genscher’s position as far too extreme but he not only needed to appease his coalition partner and calm the domestic public mood by supporting some kind of arms-reduction talks, he also had to navigate around ‘that woman’, as he called Thatcher, and keep the Alliance strong.[96]

Both the British and the Germans had been manoeuvring ahead of the summit. Thatcher met Gorbachev on 6 April in London. On a human level, the two of them had got on famously ever since their first encounter in December 1984, before he became general secretary, when she proclaimed that Gorbachev was a man with whom she could ‘do business’.[97] At their meeting in 1989 the personal chemistry was equally evident but so were their fundamental differences on nuclear policy. Gorbachev launched into a passionate speech in favour of nuclear abolition and ‘a nuclear-free Europe’ – which Thatcher totally rejected – and he vented his frustrations with Bush for not responding more positively to his disarmament initiatives. The prime minister, playing her preferred role as elder stateswoman, was at pains to reassure him: ‘Bush is a very different person from Reagan. Reagan was an idealist who firmly defended his convictions … Bush is a more balanced person, he gives more attention to detail than Reagan did. But as a whole, he will continue the Reagan line, including on Soviet–American relations. He will strive to achieve agreements that are in our common interest.’

Gorbachev jumped on those last words: ‘That is the question – in our common interests or in your Western interests?’ The reply came back: ‘I am convinced in the common interest.’ Her subtext was clearly that she was the one who could broker the relationship between the two superpowers.[98]

Privately, however, Thatcher was worried about the new US president. She had developed a close, if sometimes manipulative, rapport with ‘Ronnie’ and had felt secure about the centrality of the much-vaunted Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ in US foreign policy.[99] With Bush, the situation was less clear. It appeared that the new administration’s ‘pause’ also entailed a review of relations with Britain. And she felt that the State Department under Baker was biased against her and inclined to favour Bonn rather than London.[100] Her suspicions were not unfounded. Bush, a pragmatist, disliked Thatcher’s dogmatism and certainly did not intend to let her run the Alliance. Both he and Baker found her difficult to get on with, whereas Kohl seemed an agreeable partner.[101]

The problem in Bonn was not on the personal level but the political, because of the deep rift within the coalition. In several phone conversations during April and May, Kohl tried to reassure Bush of his loyalty to the transatlantic partnership and that he would not let the SNF issue ruin the summit. His language was almost desperate – a point not concealed even in the official American ‘telcon’ record of their talks. ‘He wanted the summit to be successful … He wanted the president to have a success. It would be the president’s first trip to Europe as president. The president was a proven friend of Europeans and, in particular, of the Germans.’[102]

The pre-summit bickering in Europe did not faze Bush. He knew that Kohl’s aim was ‘a strong NATO’ and that the chancellor had ‘linked his political existence to this goal’.[103] But the prognostications before the summit were distinctly bleak. ‘Bush Arrives for Talks With a Divided NATO’, the New York Times headlined on 29 May. The paper claimed that Bonn’s insistence on reducing the threat of SNFs to German territory raised fears in Washington, London and Paris of nothing less than the ‘denuclearisation’ of NATO’s central front. Such was the gulf, the newspaper noted, that no communiqué had been agreed in advance, which meant that NATO’s sixteen leaders would ‘have to thrash it out themselves’ at the summit. One NATO delegate confessed, ‘I honestly don’t know if a compromise is possible.’[104]

The president, however, had something up his sleeve when he arrived in Brussels. He presented his allies with a radical arms-reduction proposal not on SNFs but on conventional forces in Europe. This had not been easy to hammer out in Washington but fear of an alliance crisis in Brussels enabled Bush to bang heads together. What the president dubbed his ‘conventional parity initiative’ of 275,000 troops on each side would mean the withdrawal of about 30,000 Americans from Western Europe and about 325,000 Soviet soldiers from Eastern Europe. This was to be agreed between the superpowers within six to twelve months. Bush’s initiative was intended to probe Gorbachev’s longer-term readiness to accept disproportionate cuts that would eliminate the Red Army superiority in Eastern Europe on which Soviet domination of their satellite states had always depended. But more immediately, according to the New York Times, it was meant to ‘bring about a dramatic shift in the summit agenda’, thereby ‘swamping the missile discussion’. And this indeed proved to be the case. After nine hours of intense debate the allies accepted Bush’s proposals on cuts to conventional forces in Europe and especially his accelerated timetable. In return, the United States committed itself to ‘enter into negotiations to achieve a partial reduction of American and Soviet land-based nuclear missile forces’ as soon as the implementation of a conventional-arms accord was ‘under way’. This deal kept the Genscherites happy because of the prospect of rapid SNF negotiations, while Thatcher and Mitterrand – representing the two European nuclear powers – were gratified that there had been no further erosion of the principles of NATO’s nuclear deterrence per se. And it also suited Bush: keen to lower the conventional-warfare threat in Europe, he had been adamant that on the issue of nukes there should be ‘no third zero’.[105]

So the NATO summit that had seemed so precarious ended up as a resounding success. ‘An almost euphoric atmosphere’ surrounded the final press conference. Kohl declared ebulliently that he now perceived ‘a historic chance’ for ‘realistic and significant’ progress on arms control. He could not resist poking fun at his bête noire, Thatcher, who, he said, had come to Brussels taking a very hard line against any SNF negotiations and fiercely opposing concessions to the Germans. ‘Margaret Thatcher stood up for her interests, in her temperamental way,’ the chancellor remarked. ‘We have different temperaments. She is a woman and I’m not.’[106]

The remarkably harmonious outcome of the Brussels meeting – ‘we were all winners’, proclaimed Kohl[107] – was a big boost for NATO at forty. Indeed, he felt it was the ‘best kind of a birthday present’ the Alliance could have.[108] But it was also a huge boon for Bush, who had been under attack at home for failing to give leadership to the Alliance and for surrendering the diplomatic initiative to Gorbachev. Now, however, with his compromise package he had turned the entire situation around. As Scowcroft reflected with satisfaction, after this ‘fantastic result’ the press ‘never returned to their theme of the spring – that we had no vision and no strategy’.[109] Brussels, stated an American reporter, was ‘Bush’s hour’.[110]

As soon as the NATO press conference was over, the president travelled on to a sunlit evening in Bonn, basking in the warm glow of his success.[111] At a state dinner that night in a grand eighteenth-century restaurant, the president toasted another fortieth anniversary – that of the Federal Republic itself. ‘In 1989,’ he declared expansively, ‘we are nearer our goals of peace and European reconciliation than at any time since the founding of NATO and the Federal Republic.’ He added: ‘I don’t believe German–American relations have ever been better.’[112]

The following morning, 31 May, the Bush–Kohl caravan sailed on down the Rhine to the picture-book city of Mainz, capital of the Rhineland-Palatinate, Kohl’s home state.[113] ‘The United States and the Federal Republic have always been firm friends and allies,’ the president announced, ‘but today we share an added role: partners in leadership.’[114]

This was a striking phrase, testimony to the maturation of the American–West German relationship over the previous forty years – made ever sharper by the downgrading at the summit of Thatcher and by implication of London’s ‘special relationship’. To speak about Bonn as Washington’s ‘partner in leadership’ definitely stuck in her gullet: as she sadly admitted, it ‘confirmed the way American thinking about Europe was going’.[115]

Whereas Thatcher fixated on the partnership aspect of what Bush was saying, in his Mainz speech the president focused much more on what it meant to lead. ‘Leadership’, he declared, ‘has a constant companion: responsibility. And our responsibility is to look ahead and grasp the promise of the future … For forty years, the seeds of democracy in Eastern Europe lay dormant, buried under the frozen tundra of the Cold War … But the passion for freedom cannot be denied forever. The world has waited long enough. The time is right. Let Europe be whole and free … Let Berlin be next – let Berlin be next!’[116]

Two years before, Bush’s predecessor Ronald Reagan had stood before the Brandenburg Gate and called on the Soviet leader, ‘Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall.’[117] Now in June 1989 a new US president was throwing down the gauntlet once again, mounting a new propaganda offensive against the charismatic Soviet leader. ‘Let Berlin be next’ was in one way headline-grabbing rhetoric, but it revealed that the administration was already beginning to grapple with the issue of German unification. As Bush said in his Mainz speech, ‘the frontier of barbed wire and minefields between Hungary and Austria is being removed, foot by foot, mile by mile. Just as the barriers are coming down in Hungary, so must they fall throughout all of Eastern Europe.’ Nowhere was the East–West divide starker than in Berlin. ‘There this brutal wall cuts neighbour from neighbour, brother from brother. And that wall stands as a monument to the failure of communism. It must come down.’

Despite his emphasis on Germany, Bush’s vision remained much broader. The will for freedom and democracy, he insisted yet again, was a truly global phenomenon. ‘This one idea is sweeping across Eurasia. This one idea is why the communist world, from Budapest to Beijing, is in ferment.’[118] By June 1989, Hungary was undoubtedly on the move but here change was occurring peacefully. On the other side of the world, however, the forces of democratic protest and communist oppression collided violently and with dramatic global consequences in China’s Forbidden City.

*

On 15 May, just before noon, Mikhail Gorbachev landed at Beijing’s airport to begin a historic four-day trip to China. Descending the steps of his blue-and-white Aeroflot jet, he was greeted by the Chinese president Yang Shangkun. The two men then walked past an honour guard of several hundred Chinese troops in olive-green uniforms and white gloves. A twenty-one-gun salute boomed in the background.

The long awaited Sino-Soviet summit showed that relations between the two countries were returning to something like ‘normal’ after three decades of ideological rifts, military confrontation and regional rivalries. The Soviet leader certainly viewed his visit as a ‘watershed’. In a written statement issued to reporters at the airport, he remarked: ‘We have come to China in the springtime … All over the world people associate this season with renewal and hope. This is consonant with our mood.’ Indeed, it was anticipated that Gorbachev’s visit could seal the reconciliation of the two largest communist nations at a time when both were struggling through profound economic and political changes. ‘We have a great deal to say to each other as communist parties, even in practical terms,’ observed Yevgeny Primakov, a leading Soviet expert on Asia, ahead of the meeting. ‘This normalisation comes at a time when we are both studying how socialist countries should approach capitalism. Before, we both thought that socialism could be spread only by revolution. Today,’ he added, ‘we both stress evolution.’ There were fears in Asia and America that this summit meeting might even presage a new Sino-Soviet axis, after years when the United States had been able to capitalise on the rift between Moscow and Beijing.[119]

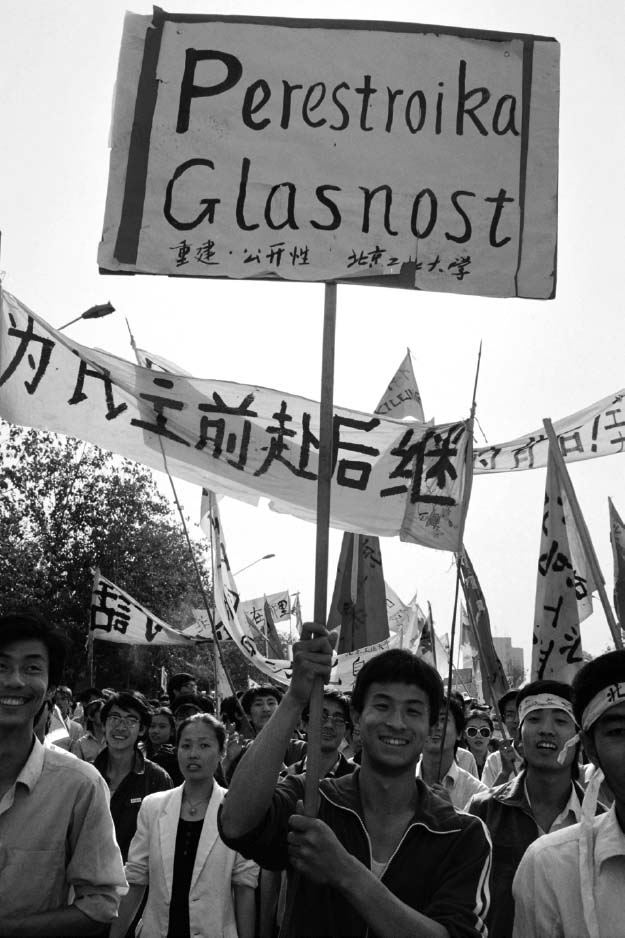

Gorbachev arrived in a city gripped by political upheaval. For over a month students from across China, but especially from Beijing, had been on the streets. Their frustrations against the authorities had been simmering for several years but the immediate trigger was the death of Hu Yaobang, former general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (1982–7) – the man who in 1986 had dared to suggest that Deng was ‘old-fashioned’ and should retire. Instead Deng and the hardliners had forced out Hu in 1987, who was then lauded by the students as a champion of reform. In the weeks after Hu died on 15 April 1989, more than a million people turned out to protest in Beijing – denouncing growing social inequality, nepotism and corruption and demanding democracy as an all-purpose panacea. What started out as law-abiding protest quickly swelled into a radical movement. And the stakes rose even higher for both sides, after the party newspaper the People’s Daily, in an editorial on 26 April, characterised the demonstrations as nothing less than ‘turmoil’ and denounced the students as ‘rioters’ with a ‘well-planned plot’ to cause anarchy. They were accused of displaying unpatriotic behaviour, of ‘attacking’ and even ‘rejecting’ the Chinese Communist Party and the socialist system.[120]

On 13 May, two days before Gorbachev’s arrival in the capital, a thousand students began a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square, bedding down on quilts and newspapers close to the monument honouring the nation’s heroes. The Soviet leader’s visit was a pivotal moment for the young Chinese protestors, for it offered an unprecedented opportunity to air their grievances while the eyes of the world were upon them. They carried banners in Russian, English and Chinese. One read ‘Welcome to a real reformer’; another ‘Democracy is our common dream’.[121] Gorbachev – a household name from the media – represented to them everything the Chinese leaders were not: a democrat, a reformer and a changemaker. Their aim was to take their case straight to him – over the heads of the regime – while embarrassing their leaders into making concessions. The students delivered a letter with 6,000 signatures to the Soviet embassy asking to meet with Gorbachev. The response was cautious. The embassy announced that the general secretary would talk with members of the public but it gave no details about who and when.[122]

New dawn for China?

The CCP leadership was caught in a cleft stick. For weeks the summit talks had been meticulously prepared: the Chinese government wanted everything to unfold without a hitch. Instead, the centre of their capital had been turned into a sea of demonstrators chanting to the world media ‘You have Gorbachev. And who do we have?’[123] The massive student protests were therefore a major embarrassment, especially considering the presence of no less than 1,200 foreign journalists, there to cover the summit but now taking every opportunity to interview protestors and broadcast live pictures of the chaos into which Beijing had descended. And the government could do nothing to stop them, for fear that repression would be beamed around the world. It was, as Deng tersely admitted, a ‘mess’. He told insiders: ‘Tiananmen is the symbol of the People’s Republic of China. The Square has to be in order when Gorbachev comes. We have to maintain our international image.’[124]

On Sunday 14 May, the day before the summit talks, the students made clear that they had no intention of complying with appeals to their patriotism by the Chinese authorities, who had called on them to clear the Square. On the contrary, some 10,000 held a vigil in the middle of Tiananmen; by daylight on Monday the crowd had swollen to an estimated 250,000. Top party officials spoke repeatedly with student leaders, promising to meet their demands for dialogue and warning of grave international embarrassment for China if they did not desist. All this was to no avail. In fact, the students’ obduracy forced a last-minute shift in Chinese protocol – changing the whole dynamic of the summit.[125]

The grand red-carpet entrée for Gorbachev up the sweeping steps of the Great Hall of the People that faces Tiananmen Square had to be abandoned. Instead there was a hastily arranged welcome ceremony at Beijing’s old airport and an incognito drive through backstreets and alleyways to enter the National People’s Congress building by a side door. Only when safely inside would Gorbachev enjoy a lavish state banquet hosted by President Yang.[126]

The situation was equally delicate for Gorbachev. The only appropriate response, it seemed, was to keep completely out of China’s internal politics and pretend that everything was running normally. But privately the Soviet delegation was shocked. Largely in the dark, they wondered whether China was falling apart. Maybe the country was in the midst of a wholesale ‘revolution’, perhaps on its political last legs? Gorbachev tried to act with appropriate ‘reserve and judiciousness’, as he put it later, but as soon as he saw the situation first-hand he felt they should leave for home as quickly as possible.[127] Obliged to speak to the press once during his visit, he offered only vague answers. He dodged questions about the protests – admitting he had seen the demonstrators with their banners demanding Deng’s resignation but saying that he would not himself assume ‘the role of a judge’ or even ‘deliver assessments’ about what was going on.[128] Of course, he said, he was personally for glasnost, perestroika and political dialogue but China was in a different situation and he was in no position to be ‘China’s Gorbachev’. Indeed, he had told his own staff on arriving that he was not keen to take the Chinese road, he did not want Red Square to look like Tiananmen Square.[129]

Conversely, the Chinese leadership did not want Beijing to go the way of Budapest or Warsaw. The visit of the prime champion of communist reform provoked intense debate within the CCP. On 13 May Deng had made clear his dogmatic hard-line position to the politically reformist Zhao Ziyang. ‘We must not give an inch on the basic principle of upholding Communist Party rule and rejecting a Western multiparty system.’ Zhao was not convinced: ‘When we allow some democracy, things might look chaotic on the surface; but these little “troubles” are normal inside a democratic and legal framework. They prevent major upheavals and actually make for stability and peace in the long run.’[130]

Prime Minister Li Peng took a position similar to Deng, with a preconceived and highly negative view of the man from the Kremlin and his reform agenda: ‘Gorbachev shouts a lot and does little,’ Li wrote in his diary. And by eroding the party monopoly on power he had ‘created an opposition to himself’, whereas the CCP had kept sole control and thereby ‘united the great majority of officials’. Li also blamed glasnost for triggering ethnic unrest inside the USSR, especially the Caucasus, and for stirring up the political upheavals in Eastern Europe. He warned that such recklessness might lead to the total break-up of the Soviet empire and spread this contagion to China itself. Deng and Li spoke for most of the inner circle, which was extremely wary of their Soviet visitor – especially given the inspirational effect he clearly had on his youthful Chinese fan club.[131]

Like Bush three months earlier, on 15 and 16 May Gorbachev met with China’s senior figures. But unlike Bush’s experience, there were no warm recollections of past times together; no intimacy or small talk. In fact, even though Yang and Li had lived for a while in the USSR as students and spoke Russian quite well, there was no personal connection between Gorbachev and his Chinese interlocutors. But, as with Bush, it was the encounter with Deng that really mattered to Gorbachev.

‘Gorbachev 58, Deng 85’[fn1] read some of the banners in the streets, contrasting the youthfulness and dynamism of the Russian leader and the conservatism of his ‘elderly’ Chinese counterpart, who would be 85 in August. Gorbachev was keen to make a good impression on Deng: trying to be tactful and deferential – for once, inclined to listen rather than talk. To let the older man speak, he reasoned, ‘is valued in the East’. The Chinese were equally sensitive to style and symbolism. They wanted to avoid all bear hugs or smooching of the sort that communist leaders so often lavished on each other. Instead they were keen to see the ‘new’ Sino-Soviet relationship, symbolised by a respectful handshake. This would be appropriate to international norms and also underline the formal equality now being established between Beijing and Moscow.[132]