Полная версия

Post Wall, Post Square: Rebuilding the World after 1989

Honecker, for his part, was determined to make an example of Leipzig. The state media replayed footage of Tiananmen and endlessly repeated the government’s solidarity with their comrades in Beijing.[26] When Honecker met Yao Yilin, China’s deputy premier, on the morning of the 9th, the two men announced that there was ‘evidence of a particularly anti-socialist action by imperialist class opponents with the aim of reversing socialist development. In this respect there is a fundamental lesson to be learned from the counter-revolutionary unrest in Beijing and the present campaign’ in East Germany. Honecker himself was positively bombastic: ‘Any attempt by imperialism to destabilise socialist construction or slander its achievements is now and in the future nothing more than Don Quixote’s futile running against the steadily turning sails of a windmill.’[27]

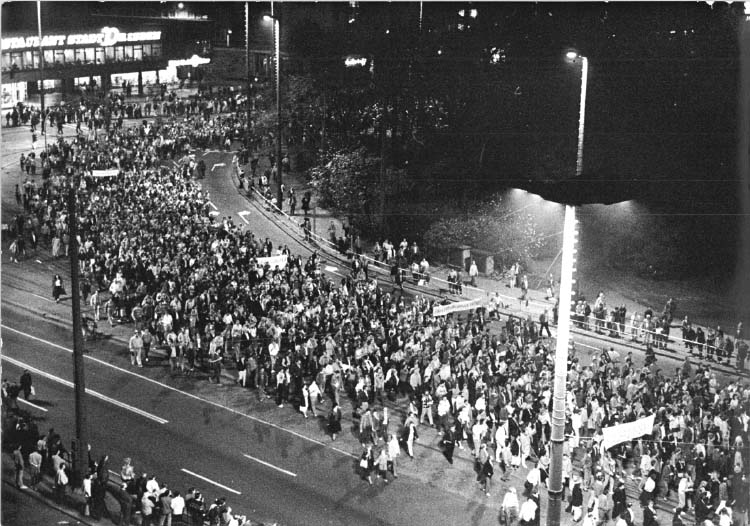

As darkness fell that evening, 9 October, with memories fresh of horrors from Berlin, many expected a total bloodbath in Leipzig. Honecker had pontificated that riots should be ‘choked off in advance’. Some 1,500 soldiers, 3,000 police and 600 paramilitary backed by hundreds of Stasi agents were ready. ‘It is either them or us,’ police were told by their superiors. ‘Fight them with no compromises,’ the interior minister ordered. The army had been given live ammunition and gas masks; the Stasi were briefed by Mielke in person; and paramilitaries and police were also called up in readiness.[28] Around 6 p.m., after prayers at the Nikolaikirche and neighbouring churches, the crowd struggled out into the streets. With more people joining the march all the time, an estimated 70,000 slowly pushed their way out onto the ring road.[29]

Marching for democracy on the Leipziger Innenstadtring

Yet the dreaded confrontation never took place. The local party was unwilling to make a move without detailed instructions from the leadership in East Berlin. The army and police were not prepared for the size of the crowd, double what they had expected. Above all, Honecker’s word was no longer law. An intense power struggle was now under way in East Berlin. Egon Krenz – twenty-five years Honecker’s junior – had been plotting a coup for some time. But, despite his recent ‘fraternal’ visit to Beijing, he did not wish to be saddled by Honecker with the opprobrium of a Tiananmen solution at home, because that would stain his own hands with German blood while allowing the elderly leader to blame him for the violence. This left the party paralysed between hardliners, ditherers and reformers. And, with no clear word that night from Berlin, the local party chief did a volte-face. Heeding the Appeal of the Six, he ordered his men to act only in self-defence. Meanwhile, the Kremlin had issued a directive to General Boris Snetkov, commander of the Western Group of Soviet Forces with his HQ in Wünsdorf near Berlin, not to intervene in East German events. The Red Army troops on East German soil were to stay in their garrisons.

So the ‘Chinese card’ was never played. Not because of a deliberate decision by the SED at the top, growing out of a change of heart, but because of the distinct absence of any decision. Time passed. The masses kept marching. There was no violence. The repressive state apparatus that Mielke had pulled together was not confronted with fearsome ‘enemies of the state’ or anarchic ‘rowdies’ but by well-disciplined ordinary citizens bearing candles and speaking the language of non-violence. What they wanted was recognition by the governing party of their legitimate quest for basic freedoms and political reform: their slogan was ‘Wir sind das Volk’ (‘We are the people’).[30]

New facts on the ground had been created. And a new demonstration culture had emerged – spilling out from the church vigils into the squares and the streets. The regime’s loss of nerve that night dispelled the omnipresent climate of fear. This would change the face of the GDR. The civil rights activists and the mass of protestors were beginning to merge.

It was a huge victory for the peaceful demonstrators and an epic defeat for the regime. ‘Die Lage ist so beschissen, wie sie noch nie in der SED war’ (‘The situation is so shitty, like it never was in the SED’), summed up one Politburo member on 17 October.[31] Next day Honecker resigned – officially on health grounds – and Krenz took over as party boss.[32] But that did not improve the public mood: the people interpreted the power transfer as the result of their pressure from below rather than as the outcome of party machinations and manoeuvrings going on ever since Honecker was taken seriously ill during the Warsaw Pact meeting in Bucharest in July.[33]

Egon Krenz at the Volkskammer as the New Party Secretary of the SED in East Berlin

Krenz promised the Party Central Committee on 18 October that he would initiate a ‘turn’ (Wende). He committed himself to open ‘dialogue’ with the opposition on two conditions: first, ‘to continue building up socialism in the GDR … without giving up any of our common achievements’ and second, to preserve East Germany as a ‘sovereign state’. As a result, Krenz’s Wende amounted to little more than a rhetorical tweak of the party’s standard dogma. And, in similar vein, the personnel changes he made among the leadership were largely cosmetic. There was, in short, little genuine ‘renewal’ in the offing: clearly Wende did not mean Umbruch (rupture and radical change).[34]

Not only did Krenz’s accession to power leave more reformist elements in the SED frustrated; worse, he personally appeared clueless in judging the true nature of the public mood. After his election to the post of SED general secretary, he asked the Protestant church leaders when ‘those demonstrations finally would come to end’. After all, continued Krenz obtusely, ‘one can’t spend every day on the streets’.[35] Little did he know.

In any case, Krenz was not a credible leader. Rumours were rife about his health and his alcohol problems. And ‘long-tooth’ Krenz, as he was nicknamed – a party hack for more than thirty years – had no plausibility as a ‘reformer’. So, rather than stabilising SED rule, his takeover actually served to fuel popular displeasure with the party and accelerated the erosion of its monopoly on power. What’s more, when the Krenz regime renounced the open use of force, that token concession only emboldened the masses to demand ever more fundamental change. They now felt they were pushing at an open door: ‘street power’ was shaking ‘the tower’.[36]

After the fall of Honecker on 18 October, anti-government protest – in the form of peace prayers, mass demonstrations and public discussions – spread right across the country. In the process various currents of criticism flowed together into a surging tide. Long-time dissidents from the churches; writers and intellectuals from the alternative left; critics of the SED from within the party; and the mass public spilling out onto the streets: all these fused in what might be called an independent public sphere. They spoke in unison for people’s sovereignty. Discontent was now open. The long spell of silence had been broken.

On 23 October in Leipzig, 300,000 participated in the Monday march around the ring road. In Schwerin on the Baltic, the ‘reliable forces’ who were meant to come out for the regime ended up in large swathes joining the parallel demo by Neues Forum. Next day the protests returned to East Berlin, whose squares had remained quiet since the brutal crackdown of 7 and 8 October. Overall, there were 145 anti-government events in the GDR in the last week of the month, and a further 210 in the first week of November. Not only were these protests growing, the demands were becoming both more diverse and also more pointed:

Die führende Rolle dem Volk (‘The leading role to the people’, 16 October)

Egon, leit Reformen ein, sonst wirst Du der nächste sein! (‘Egon, introduce reforms, or else you’ll be next!’, 23 October)

Visafrei bis Hawaii! (‘Visa-free travel to Hawaii!’, 23 October)

Demokratie statt Machtmonopol der SED (‘Democracy instead of the SED’s monopoly on power’, 30 October)

Conversely, the SED leadership appeared lost for words. Increasingly unable to win the argument, the Krenz Politburo hid behind traditional orthodoxy.[37] In particular, the party was totally unwilling to give up its constitutionally entrenched ‘leading role’ (Führungsanspruch) – which was the principal demand of all those who wanted liberalisation and democratisation.[38] To make matters worse, while seeking to reinstate its authority, the regime showed itself bewildered and helpless in the face of the GDR’s deteriorating economic situation. Discussions in the Politburo revolved around how to get consumers more tyres, more children’s anoraks, more furniture, cheaper Walkmen and how to mass-produce PCs and 1 MB chips – not the structural flaws of the economy.[39]

Only on 31 October were the stark realities finally laid bare in an official report to the Politburo by the chief planner, Gerhard Schürer, on the economic state of the GDR. The country’s productivity was 40% lower than that of the Federal Republic. The system of state planning had proved totally unfit for purpose. And the GDR was close to national insolvency. Indebtedness to the West had risen from 2 billion Valutamarks in 1970 to 49 billion in 1989.[fn1] Merely halting further indebtedness would entail a lowering of the East Germans’ living standards by 25–30% in order to service the existing debt. And any default on debt repayments would risk opening the country to an IMF diktat for a market economy under conditions of acute austerity. For the SED, this was ideologically untenable. In May, Krenz had declared that economic policy and social policy were an entwined unit, and had to be continued as such because this was the essence of socialism in the GDR. So the regime was trapped in a vicious circle: socialism depended on the Plan, and the survival of the planned economy required external credits on a scale that now made East Germany totally dependent on the capitalist West, especially the FRG.[40]

Straight after this fateful Politburo meeting, Krenz flew to Moscow for his first visit to the Kremlin as the GDR’s secretary general. There on 1 November he admitted the economic home truths to Gorbachev himself. The Soviet leader was unsympathetic. He coldly informed Krenz that the USSR had been aware of East Berlin’s predicament all along; that was why he had kept pressing Honecker for reforms. Even so, when Gorbachev heard the precise figures – Krenz said the GDR needed $4.5 billion in credits simply to pay off the interest on its debts – the Soviet leader was, for a moment, speechless – a rare occurrence. The Kremlin was in no position to help, so Gorbachev could only advise Krenz to tell his people the truth. And, for a country that had already haemorrhaged over 200,000 alienated citizens since the start of 1989, this was not a happy prospect.[41]

Afterwards, Krenz tried to put the best face on things in a seventy-minute meeting with the foreign press, presenting himself as an ‘intimate friend’ of Gorbachev and no hardliner. But the media were not convinced. When Krenz talked policy, he sounded just like Honecker, his political mentor, and he flatly rejected any talk of reunification with West Germany or the removal of the Berlin Wall. ‘This question is not on the table,’ Krenz insisted. ‘There is nothing to reunify because socialism and capitalism have never stood together on German soil.’ Krenz also put a positive spin on the mass protests. ‘Many people are out on the streets to show that they want better socialism and the renovation of society,’ he said. ‘This is a good sign, an indication that we are at a turning point.’ He added that the SED would seriously consider the demands of the protestors. The first steps, he said, would be taken at a party meeting the following week.[42]

In truth, the SED had its back to the wall. Desperate, it decided to give ground to the protestors on the question of travel restrictions – to allow an appearance of freedom. So on 1 November the GDR reopened its borders with Czechoslovakia. The result was no surprise, except perhaps to the Politburo itself. Once again the people voted with their feet: some 8,000 left their Heimat on the first day. On 3 November, Miloš Jakeš, leader of the Czech communists in Prague – having secured Krenz’s approval – formally opened Czechoslovakia’s borders to the FRG, thereby granting East Germans a legal transit route to the West. But instead of this halting the frenzied flight, the exodus only continued to grow: 23,000 East Germans arrived in the Federal Republic on the weekend of 4–5 November, and by the 8th the total number of émigrés had reached 50,000.[43]

On his return home Krenz pleaded with East Germans in a televised address. To those who thought of emigrating, he said: ‘Put trust in our policy of renewal. Your place is here. We need you.’[44] That last sentence was true: the mass flight that autumn had already caused a serious labour shortage in the economy, especially in the health sector. Hospitals and clinics had reported losing as many as 30% of their staff as doctors and nurses had succumbed to the lure of freedom, much better pay and a more high-tech work environment in the West.[45]

By this stage, few were listening to the SED leader. On 4 November half a million attended a ‘rally for change’ in East Berlin, organised by the official Union of Actors. For the first time since the fortieth-anniversary weekend, there was no police interference in the capital. Indeed, the rally – which included party officials, actors, opposition leaders, clergy, writers and various prominent figures – was broadcast live on GDR media. Speakers from the government were shouted down, with chants of ‘Krenz Xiaoping, no thanks’. Others, such as the novelist Christa Wolf, drew cheers as she announced her dislike for the party’s language of ‘change of course’. She said she preferred to talk of a ‘revolution from below’ and ‘revolutionary renewal’.

Wolf was one of thousands of opposition activists who desired a better, genuinely democratic and independent GDR. Quite definitely they did not see the Federal Republic as the ideal. They did not want their country to be gobbled up by the dominant, larger western half of Germany – in a cheap sell-out to capitalism. People like Wolf and Bärbel Bohley, the artist founder of Neues Forum, had stuck with the GDR despite all its frustrations; in their minds, running away was the soft option. So they now wanted to reap the fruit of their hard work as dissidents. They were idealists who aspired to a democratic socialism, and saw the autumn of 1989 as their chance to turn dreams into reality.

But Ingrid Stahmer, the deputy mayor of West Berlin, had a different perspective. With GDR citizens now freely flooding out of the country through its Warsaw Pact neighbours, she remarked that the Wall was soon going to become history. ‘It’s just going to be superfluous.’[46]

On Monday 6 November, close to a million people in eight cities across the GDR –some 400,000 in Leipzig and 300,000 in Dresden – marched to demand free elections and free travel. They denounced as totally inadequate the latest loosening of the travel law, published that morning in the state daily Neues Deutschland, because it limited foreign travel to thirty days. And there was a further question: how much currency would East Germans be allowed to change into Western money at home? The Ostmark was not freely convertible, and up to now East Germans had been allowed once a year to exchange just fifteen Ostmarks into DMs – about $8 at the official exchange rate – hardly enough for a meal, let alone an extended trip.[47]

So the pressure was intense when the SED Central Committee gathered on 8 November for its three-day meeting. Right at the start, the entire Politburo resigned and a new one – reduced in size from twenty-one members to eleven – was elected, to create the appearance of change. In the event, six members retained their seats, while five new ones were named. Three of Krenz’s preferred new Politburo candidates were rejected and the party gave the position of prime minister to Hans Modrow, the SED chief in Dresden – a genuine reformer. As a result, the party elite was now visibly split. What’s more, on the outside of the party headquarters, 5,000 SED members protested openly against their leaders.[48]

Next day, 9 November, the party struggled to think up responses to people’s demands in the streets. In late afternoon the Central Committee came back to the problematic travel regulations. A short memo was drawn up and passed to the secretary of the Central Committee, Günter Schabowski, who had been appointed that morning as the SED’s media spokesman but did not attend that part of the discussions. At 6 p.m. Schabowski briefed the world media on the day’s deliberations, in a press conference broadcast live on GDR TV.[49]

It was a long and boring meeting. Near the end Schabowski was asked by one journalist about the alterations in the GDR travel law. He offered a rather incoherent summary and then, under pressure, hastily read out parts of the press statement he had been given earlier. Distracted by further questions he omitted the passages regarding the grounds for denying applications both for private travel and permanent exit applications. His omissions, however, only added to the confusion. Had the Central Committee radically changed its course? A now panicky Schabowski talked of a decision to allow citizens to emigrate permanently. The press room grew restless. The media started to get their teeth into the issue.

What about holidays? Short trips to the West? Visits to West Berlin? Which border crossings? When would the new arrangements come into effect? A seriously rattled Schabowski simply muttered ‘According to my knowledge … immediately, right away.’ Because they had not been given any formal written statement, the incredulous press corps hung on Schabowski’s every word, squeezing all they could out of them.[50]

Finally someone asked the fatal question: ‘Mr Schabowski, what is going to happen to the Berlin Wall now?’

Schabowski: It has been brought to my attention that it is 7 p.m. That has to be the last question. Thank you for your understanding.

Um … What will happen to the Berlin Wall? Information has already been provided in connection with travel activities. Um, the issue of travel, um, the ability to cross the Wall from our side … hasn’t been answered yet and exclusively the question in the sense … so this, I’ll put it this way, fortified state border of the GDR … um, we have always said that there have to be several other factors, um, taken into consideration. And they deal with the complex of questions that Comrade Krenz, in his talk in the – addressed in view of the relations between the GDR and the FRG, in ditto light of the, um, necessity of continuing the process of assuring peace with new initiatives.

And, um, surely the debate about these questions, um, will be positively influenced if the FRG and NATO also agree to and implement disarmament measures in a similar manner to that of the GDR and other socialist countries. Thank you very much.

The media was left to make what they wanted of his incoherence. The press room emptied within seconds. The news went viral on the wire services and soon made its way via TV and radio into living rooms and streets of Berlin. ‘Leaving via all GDR checkpoints immediately possible’ Reuters reported at 7.02 p.m., ‘GDR opens its borders’, echoed Associated Press three minutes later. At 8 p.m. on West German TV, the evening news Tagesschau – which millions of East Germans could watch – led with the same message. Correct in substance, these headlines were, of course, in formulation much balder, bolder and far-reaching than the small print of the actual East German Reiseregelung, or the reality on the ground.[51]

But during the course of this damp and very cold November evening, reality soon caught up – and with a vengeance.

Over the next few hours, thousands of East Berliners converged on the various checkpoints at the Wall, especially in the centre of the city – to see for themselves if and when they could cross. They were not put off by East German state television or the police telling them to come back next morning at eight o’clock when the bureaucracy would be all ready. Instead they kept shouting: ‘Tor auf!’ (‘Open the gate!’). At Bornholmer Strasse, some sixty armed border guards – commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Harald Jäger, who had been doing the job since 1964 – sat in their tiny checkpoint huts, totally outnumbered, and without any instructions from on high. Both the Central Committee and the military top brass, locked away in meetings, were unreachable. So the men on the front line had to make their own decisions. At around 9 p.m. they began to let people through: first as a trickle, one by one, meticulously stamping each person’s identity card – the idea being these exiters would not later be let back in. Then, at around 10.30 p.m., they lifted the barriers in both directions and gave up trying to check credentials. It was as if the floodgates had been opened. People poured across into West Berlin. No East or West German politicians were present, nor any representatives of the four occupying powers. There were just a few baffled East German men in uniform, soon reduced to tears as they were overcome by the emotion of this historic moment.[52]

Within thirty minutes, several thousand people had squeezed their way to the other side. Somewhere in the chaos a young East German quantum chemist called Angela Merkel was swept along by the crowd. After a quiet sauna evening with her friends, she just wanted to experience for herself German history in the making. Once on the western side of the Wall, she phoned her aunt in Hamburg and joined the celebrations before heading back home – wondering what 9 November would mean for her.[53]

By midnight – after twenty-eight years of sealed borders – all the crossings in Berlin were open; likewise, as news spread, any other transit point along the border between the two Germanies. Neither the GDR security forces nor the Red Army did anything to prevent this. Not a single shot was fired, and no Soviet soldier left his barracks. Now, thousands of East Berliners – of all ages, from every walk of life – were making their way on foot, bike or car into the western half of the city – a forbidden place hitherto only glimpsed from afar. At Checkpoint Charlie, where Allied and Soviet tanks had been locked in a tense face-off in August 1961 as the Berlin Wall went up, the jubilant horde of visitors was greeted by cheering, flag-waving West Germans, plying them with flowers and sparkling wine.

‘I don’t know what we’re going to do, just drive around and see what’s going on,’ said one thirty-four-year-old East Berliner as he sat at the wheel of his orange Trabant chugging down the glittering Kurfürstendamm. ‘We’re here for the first time. I’ll go home in a few hours. My wife and kids are waiting for me. But I wasn’t going to miss this.’[54]

At the Brandenburg Gate, the most prominent landmark of the city’s division, hundreds of people chanted on the western side ‘The Wall must go!’ Then some climbed on top of the Wall and danced on it; others clambered over and headed right through the historic arch that for so long had been inaccessible to Berliners from either side. These were utterly unbelievable pictures – captured gleefully by American TV film crews for their prime-time news bulletins back home.[55]

All through the night and over the next few days, East Berliners continued to flood into West Berlin in vast numbers – 3 million in three days, most of whom came back.

The open Wall: Potsdamer Platz, 12 November 1989