полная версия

полная версияHistory of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2

523

It was not, as will be remarked, the countervallation which was 11,000 feet in extent, but the line of investment.

524

Eadem altitudine. See paragraph XIII., Details on the Excavations of Alesia, page 364.

525

Dolabratis, diminished to a point, and not delibratis, peeled.

526

In the excavations at Alesia, five stimuli have been found, the form of which is represented in Plate 27. The new names which Cæsar’s soldiers gave to these accessory defenses prove that they were used for the first time.

527

This appears from a passage in De Bello Civili, III. 47.

528

529

See note on page 143.

530

This passage proves clearly that the army of succour attacked also the circumvallation of the plain. In fact, how can we admit that, of 240,000 men, only 60,000 should have been employed? It follows, from the accounts given in the “Commentaries,” that among this multitude of different peoples, the chiefs chose the most courageous men to form the corps of 60,000 which operated the movement of turning the hills; and that the others, unaccustomed to war, and less formidable, employed in the assault of the retrenchments in the plain, were easily repulsed.

531

According to Polyænus (VIII. xxiii. 11), Cæsar, during the night, detached 3,000 legionaries and all his cavalry to take the enemy in the rear.

532

“Cæsar (at Alexandria) was greatly perplexed, being burdened with his purple vestments, which prevented him from swimming.” (Xiphilinus, Julius Cæsar, p. 26.) – “Crassus, instead of appearing before his troops in a purple-coloured paludamentum, as is the custom of the Roman generals…” (Plutarch, Crassus, 28.)

533

“The inhabitants of Alesia despaired of their safety when they saw the Roman soldiers bringing from all sides into their camp an immense quantity of shields ornamented with gold and silver, cuirasses stained with blood, plate, and Gaulish flags.” (Plutarch, Cæsar, 30.)

534

Florus, III. x. 26. – According to Plutarch (Cæsar, 30), Vercingetorix, after having laid down his arms, seated himself in silence at the foot of Cæsar’s tribunal.

535

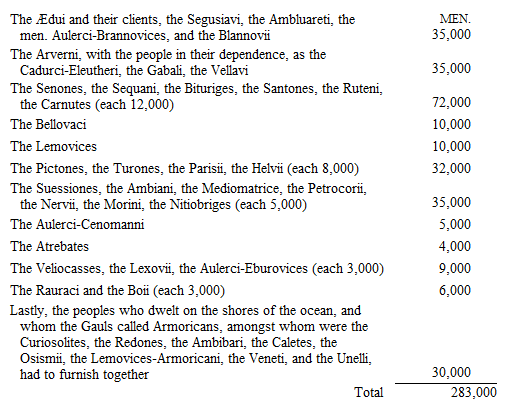

De Bello Gallico, VII. 90. – By comparing the data of the VIIth book with those of the VIIIth, we obtain the following results:

536

There have been found, on a length of 200 mètres, in the bottom of the upper fosse, ten Gaulish coins, twenty arrow-heads, fragments of shields, four balls of stone of different diameters, two millstones of granite, skulls and bones, earthenware, and fragments of amphoras in such quantity, that it would lead us to suppose that the Romans threw upon the assailants everything that came to hand. In the lower fosse, near which the struggle was hotter after the sally of Labienus, the result has surpassed all hopes. This fosse has been opened for a space of 500 mètres in length from X to X (see Plate 25): it contained, besides 600 coins (see Appendix C), fragments of pottery, and numerous bones, the following objects: ten Gaulish swords and nine scabbards of iron, thirty-nine pieces which belonged to arms of the description of the Roman pilum, thirty heads of javelins, which, on account of their lightness, are supposed to have been the points of the hasta amentata; seventeen more heavy heads may also have served for javelins thrown by the amentum, or simply by the hand, or even for lances; sixty-two blades, of various form, which present such finished workmanship that they may be ranged among the spears.

Among objects of defensive armour there have been found one iron helmet and seven cheek-pieces, the forms of which are analogous to those which we see represented on Roman sculptures; umbos of Roman and Gaulish shields; an iron belt of a legionary; and numerous collars, rings and fibulæ.

537

In the fosses of the plain of Laumes have been found a fine sword, several nails, and some bones; on the left bank of the Oserain, two coins, three arrow-heads, and other fragments of arms; in the fosse which descends towards the Ose, on the northern slopes of Mont Penneville, a prodigious quantity of bones of animals. A spot planted with vines, close by, on the southern slope of Mont Penneville, is still at the present day called, on the register of lands, Cæsar’s Kitchen (la Cuisine de César).

538

In the fosses of the circumvallation in the plain of Laumes have been found stone balls, some fragments of arms, pottery, and a magnificent silver vase, of good Greek art. This last was found at z (see Plate 25), near the imperial road from Paris to Dijon, at the very bottom of the fosse, at a depth of 1·40m. Bronze arms, consisting of ten spears, two axes, and two swords, have been found previously at y near the Oserain.

539

This book, as is known, was written by Hirtius.

540

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 5.

541

Viz., the Aulerci-Eburovices.

542

It has been objected that Mont Saint-Pierre was not sufficiently large to contain seven legions; but, since Cæsar for a long while had only four legions with him, the camp was made for that number. Afterwards, instead of remaining on the defensive, he determined, as at Alesia, to invest the Gaulish camp, and it was then only that he sent for three more legions. The appearance of the different camps which have been found is, on the contrary, very rational, and in conformity with the number of troops mentioned in the “Commentaries.” Thus, the camp of Berry-au-Bac, which contained eight legions, had forty-one hectares of superfices; that of Gergovia, for six legions, had thirty-three hectares; and that of Mont Saint-Pierre, for four legions, twenty-four hectares.

543

“Non solum vallo et sudibus, sed etiam turriculis instruunt… quod opus loriculam vocant.” (Vegetius, IV. 28.)

544

It may be seen, by the profiles of the fosses which have been brought to light, that they could not have had vertical sides; the expression used by Hirtius leads us to believe that, by lateribus directis, he meant fosses not triangular, but with a square bottom.

545

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 17.

546

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 23.

547

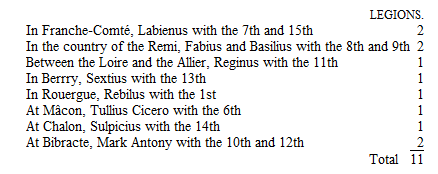

Rebilus had at first only one legion; we believe, with Rustow, that the 10th, which was quartered at Bibracte, had come to join him. It is said (VII. 90) that Rebilus had been sent to the Ruteni; but it appears, from a passage of Orosius (VI. 11), “that he was stopped on his way by a multitude of enemies, and ran the greatest dangers.” He remained, therefore, in the country of the Pictones, where Fabius came to his succour.

548

Some manuscripts read erroneously the 13th legion.

549

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 25.

550

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 31.

551

See his biography in Appendix D.

552

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 44.

553

It is due to the persevering research of M. J. B. Cessac, assisted subsquently by the departmental commission of the Lot.

554

List of the objects found at Puy-d’Issolu: one blade of a dolabrum, thirty-six arrow-heads, six heads of darts for throwing by catapults, fragments of bracelets, bear’s tooth (an amulet), necklace beads, rings, a blade of a knife, and nails.

555

According to Frontinus (Stratag., II. 11), Commius sought an asylum in Great Britain.

556

De Bello Gallico, VIII. 48.

557

Plutarch, Marius, 19.

558

Mémoires de Napoléon I., Revolt of Pavia, VII. 4.

559

For the clearer intelligence of the recapitulation, we have adopted the modern names of the different people of Gaul, although these names are far from answering to their ancient boundaries.

560

Cicero, when proconsul in Cilicia, obtained the sum of twelve millions of sesterii (2,280,000 francs) from the sale of prisoners made at the siege of Pindenissus. (Cicero, Epistolæ ad Atticum, V. 20.)

561

Julian (Cæsares, p. 72, edit. Lasius) makes Cæsar say that he had treated the Helvetii like a philanthropist, and rebuilt their burnt towns.

562

It was probably at this time that the chiefs of Auvergne, and perhaps Vercingetorix himself, as Dio Cassius tells us, came to render homage to the Roman proconsul. (See above, p. 80.)

563

Mommsen, Römische Geschichte, III., p. 291. Berlin, 1861.

564

Plutarch, Pompey, 51, 52.

565

“He soon allowed himself to be enervated by his love for his young wife. Entirely occupied in pleasing her, he passed whole days with her in his country house or in his gardens, and ceased to think of public affairs. Thus even Clodius, then tribune of the people, regarding him no longer with anything but contempt, dared to embark in the rashest enterprises.” (Plutarch, Pompey, 50.)

566

Dio Cassius, XXXVIII. 13.

567

Plutarch, Pompey, 51, 52.

568

Dio Cassius, XXXVIII. 30.

569

Plutarch, Pompey, 48 and 50.

570

“Pompey is going at last to labour on my recall: he only waited for a letter from Cæsar to cause the proposal to be made by one of his partisans.” (Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, III. 18.) – “If Cæsar has abandoned me, if he has joined my enemies, he has been unfaithful to his friendship, and has done me an injury; I ought to have been his enemy, I deny it not; but if Cæsar has interested himself in my restoration, if it be true that you thought it important for me that Cæsar should not be opposed,” &c… (Orat. de Provinciis Consularibus, 18.)

571

“It was then that P. Sextius, the tribune nominate, repaired to Cæsar to interest him in my recall. I say only that if Cæsar were well intentioned towards me, and I believe he was, these proceedings added nothing to his good intentions. He (Sextius) thought that, if they wished to restore concord among the citizens and decide on my recall, they must secure the consent of Cæsar.” (Cicero, Pro Sextio, 33)

572

“Pompey took my brother as witness that all he had done for me he had done by the will of Cæsar.” (Cicero, Epist. Familiar., I. 9.)

573

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 31, et seq.

574

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 31.

575

Plutarch, Pompey, 51. – Cicero, Pro Sextio, 32; De Responsu Haruspic., 23: Pro Milone, 7. – Asconius, Comment. in Orat. pro Milone, p. 47, edit. Orelli.

576

Plutarch, Pompey, 51. – Cicero, Pro Milone, 7. – Asconius, Comment. in Orat. pro Milone, p. 47, edit. Orelli.

577

Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, III. 23. – Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 6.

578

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 33.

579

Cicero, Orat. pro Domo sua, 27; Pro Sextio, 34.

580

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 34; De Legibus, III. 19.

581

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 34.

582

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 35. – Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 7. – Plutarch, Pompey, 51.

583

Cicero, Pro Sextio, 35; Orat. prima post Reditum, 5, 6.

584

Cicero, De Officiis, II. 17; Orat. pro Sextio, 39. – Dio Cassius XXXIX. 8.

585

Cicero, Orat. secunda post Reditum ad Senatum, 10; Orat. pro Domo sua, 28; Orat. in Pisonem, 15.

586

We thus see that the power of observing the sky continued to exist in spite of the law Clodia.

587

Cicero, in the passages cited.

588

Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, IV, 1.

589

Asconius, Comment in Orat. Ciceronis pro Milone, p. 48, edit. Orelli.

590

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 9. – Plutarch, Pompey, 52.

591

Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, IV. 1. – Cicero’s proposal was further amplified by C. Messius, tribune of the people, who demanded for Pompey a fleet, an army, and the authority to dispose of the finances.

592

Plutarch, Pompey, 52. – Cicero, Orat. pro Domo sua, 10.

593

Epist. ad Attic., IV. 2.

594

“I will add that, in the opinion of the public, Clodius is regarded as a victim reserved for Milo.” (Cicero, De Respons. Harusp., 3.) – This oration on the reply of the Aruspices is of May, June, or July, 698. See, also, what he says in his letter to Atticus, of November, 697. (Epist. ad Attic. IV. 3.)

595

Plutarch, Cæsar, 23. —De Bello Gallico, II. 35.

596

“But why, especially on that occasion, should any one be astonished at my conduct or blame it, when I myself have already several times supported propositions which were more honourable for Cæsar than necessary for the state? I voted in his favour fifteen days of prayers; it was enough for the Republic to have decreed to Cæsar the same number of days which Marius had obtained. The gods would have been satisfied, I think, with the same thanksgivings which had been rendered to them in the most important wars. So great a number of days had therefore for its only object to honour Cæsar personally. Ten days of thanksgivings were accorded, for the first time, to Pompey, when the war of Mithridates had been terminated by the death of that prince. I was consul, and, on my report, the number of days usually decreed to the consulars was doubled, after you had heard Pompey’s letter, and been convinced that all the wards were terminated on land and sea. You adopted the proposal I made to you of ordaining ten days of prayers. At present I have admired the virtue and greatness of soul of Cn. Pompey, who, loaded with distinctions such as no other before him had received the like, gave to another more honours than he had obtained himself. Thus, then, those prayers which I voted in favour of Cæsar were accorded to the immortal gods, to the customs of our ancestors, and to the needs of the state; but the flattering terms of the decree, this new distinction, and the extraordinary number of days, it is to the person itself of Cæsar that they were addressed, and they were a homage rendered to his glory.” (Cicero, Orat. pro Provinc. Consular., 10, 11.) (August, A.U.C. 698.)

597

Cicero, Epist. ad Quint., II. 1.

598

Cicero, Epist. ad Quint., II. 1.

599

Cicero, Epist. ad Quint., II. 1.

600

Cicero, Epist. ad Attic., IV. 3.

601

Cicero, Epist. ad Attic., IV. 2 and 3; Epist. ad Quint., II. 1.

602

Atia had wedded in first marriage Octavius, by whom she had a son, who was afterwards Augustus.

603

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 14.

604

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 12, 13. – Plutarch, Pompey, 52.

605

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 14. – “I do not spare upon him even reproaches, to prevent him (Pompey) from meddling in this infamy.” Cicero, Epist. Famil., I. 1.

606

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 15.

607

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 2.

608

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 16.

609

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 2. – Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 18.

610

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 18, 19.

611

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3.

612

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 20.

613

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3.

614

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3.

615

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3. – We look upon this word as giving the explanation of the quarrel then existing between the two triumvirs. Egypt was so rich a prey, that it was calculated to cause division between them.

616

“Clodius is cast down from the tribune, and I steal away, for fear of accident.” (Cicero, Ep. ad Quint., II. 3.)

617

Cicero, Ep. ad Quint., II. 3.

618

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 22.

619

Plutarch, Cato, 45, tells us that Cato returned under the consulship of Marcius Philippus.

620

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 23.

621

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 7.

622

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 1.

623

Plutarch, Cato, 40; Cicero, 45.

624

“There has reached me a mass of private talk of people here, whom you may guess, who have always been, and always are, in the same ranks with me. They openly rejoice at knowing that I am, at the same time, already on terms of coolness with Pompey, and on the point of quarrelling with Cæsar; but what was most cruel was to see their attitude towards my enemy (Clodius), to see them embrace him, flatter him, coax him, and cover him with caresses.” (Cicero, Epist. Familiar., I. 9.)

625

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3.

626

These words are reported by Cicero (Epist. ad Quintum, II. 3), to whom they were addressed by Pompey. Dio Cassius, contrary to all probability, pretends that Pompey, from this moment, was irritated against Cæsar, and sought to deprive him of his province. There is no proof of such an allegation. The interview at Lucca, which took place this same year, offers a formal contradiction to it.

627

See Nonius Marcellus (edit. Gerlach and Roth, p. 261), who quotes a passage from Book XXII. of the Annals of Fenestella, who wrote under Augustus or Tiberius.

628

Suetonius, Cæsar, 24.

629

Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 5.

630

Cicero, Epist. Familiar., I. 9.

631

“The question of the lands of Campania, which ought to have been settled on the day of the Ides and the day following, is not yet decided. I have much difficulty in making up my mind on this question.” (Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 8.) (April, 698.)

632

“Appius is not yet returned from his visit to Cæsar.” (Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 6.) (April, 698.)

633

“Knowing well that small news as well as great news have reached Cæsar.” (Epist. ad Quintum, III. i. 3.)

634

Dio Cassius, XXXIX. 25.

635

Plutarch, Cæsar, 24.

636

“Appius, he says, has visited Cæsar, in order to wrest from him some nominations of tribunes.” (Cicero, Epist. ad Quintum, II. 15.)

637

Appian, Civil Wars, II. 17. – The consuls and proconsuls had twelve lictors, the prætors six, the dictators twenty-four, and the master of the cavalry a number which varied. The curule ædiles, the quæstors, and the tribunes of the people, not having the imperium, had no lictors. As, at the time of the conference of Lucca, there was no dictator or master of cavalry, the number of 120 fasces can only apply to the collective escort of proconsuls and prætors. It is not probable that the two consuls then in office at Rome should have gone to Lucca. On the other hand, the proconsuls were prohibited from quitting their provinces as long as they were in the exercise of their commands. (see Titus Livius, XLI. 7; XLIII. 1.) But as the conferences of Lucca took place just at the epoch when the proconsuls and proprætors were starting for their provinces (we know from Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, III. 9, that this departure took place in the months of April and May), it is probable that the newly-named proconsuls and proprætors repaired to Lucca before they went to take possession of their commands. Thus the number of 120 fasces would represent the collective number of the lictors of proprætors or proconsuls who could pass through Lucca before embarking either at Pisa, or Adria, or at Ravenna.

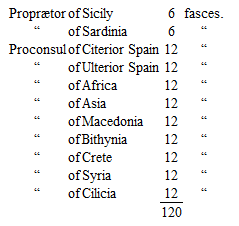

On this hypothesis, we should have the following numbers: —

Plutarch (Pompey, 53) says in so many words that there were seen every day at his door 120 fasces of proconsuls and prætors.

638

Appian, Civil Wars, II. 17.

639

See Suetonius, Cæsar, 24. – The proof that this plan originated with Cæsar is found in the fact that Pompey and Crassus had not previously taken any steps to ensure their election.

640

We have put into the mouth of Cæsar the following words of Cicero: “In giving the Alps as a boundary to Italy, Nature had not done it without a special intention of the gods. If the entrance had been open to the ferocity and the multitude of the Gauls, this town would never have been the seat and centre of a great empire. These lofty mountains may now level themselves; there is now nothing, from the Alps to the ocean, which Italy has to fear. One or two campaigns more, and fear or hope, punishments or recompenses, arms or the laws, will reduce all Gaul into subjection to us, and attach her to us by everlasting ties.” (Cicero, Orat. de Provinciis Consularibus, 14.